A close look at the budgetary numbers offers critical insights into government spending in two vital areas: education and health.

Schools across the country remain underfunded, with many lacking even basic infrastructure. The crisis is so severe that the suicide rate among students has now surpassed that of farmers, a grim reflection of the pressure and neglect in the education sector.

Healthcare paints an equally dire picture where India is short by a staggering 2.4 million hospital beds, leaving millions without access to proper medical treatment. India, which is meant to be utilising its demographic advantage, seems instead to be overlooking its most valuable asset: people.

Education: Budgetary allocations and systemic inefficiencies

Education has long been touted as the foundation of India’s future, yet budgetary allocations and systemic inefficiencies tell a different story. Public expenditure on education remains around 2.9 per cent of GDP (2024), far below the 6 per cent target recommended by the Kothari Commission. While funding has increased since 2015-16, the sector continues to grapple with severe infrastructure and manpower shortages.

One of the most pressing concerns is the acute shortage of qualified teachers. Over 1.2 million teacher vacancies exist nationwide, leading to overcrowded classrooms with student-teacher ratios exceeding 50:1 in many government schools. Worse, nearly 40 per cent of government-appointed teachers lack proper qualifications, severely impacting learning outcomes. In rural areas, these issues are compounded by poor infrastructure, outdated curricula, and the digital divide, which seriously hampers the quality of education for millions.

Also Read | Budget 2025-26: The true cost of expanding social welfare schemes

The cracks in the system manifest in tragic ways. India has one of the highest youth suicide rates in the world, with one student dying every 42 minutes in 2020. That year there were 11,396 student suicides, most attributed to academic pressure, parental expectations, and anxiety. Yet, mental health support in schools remains largely absent.

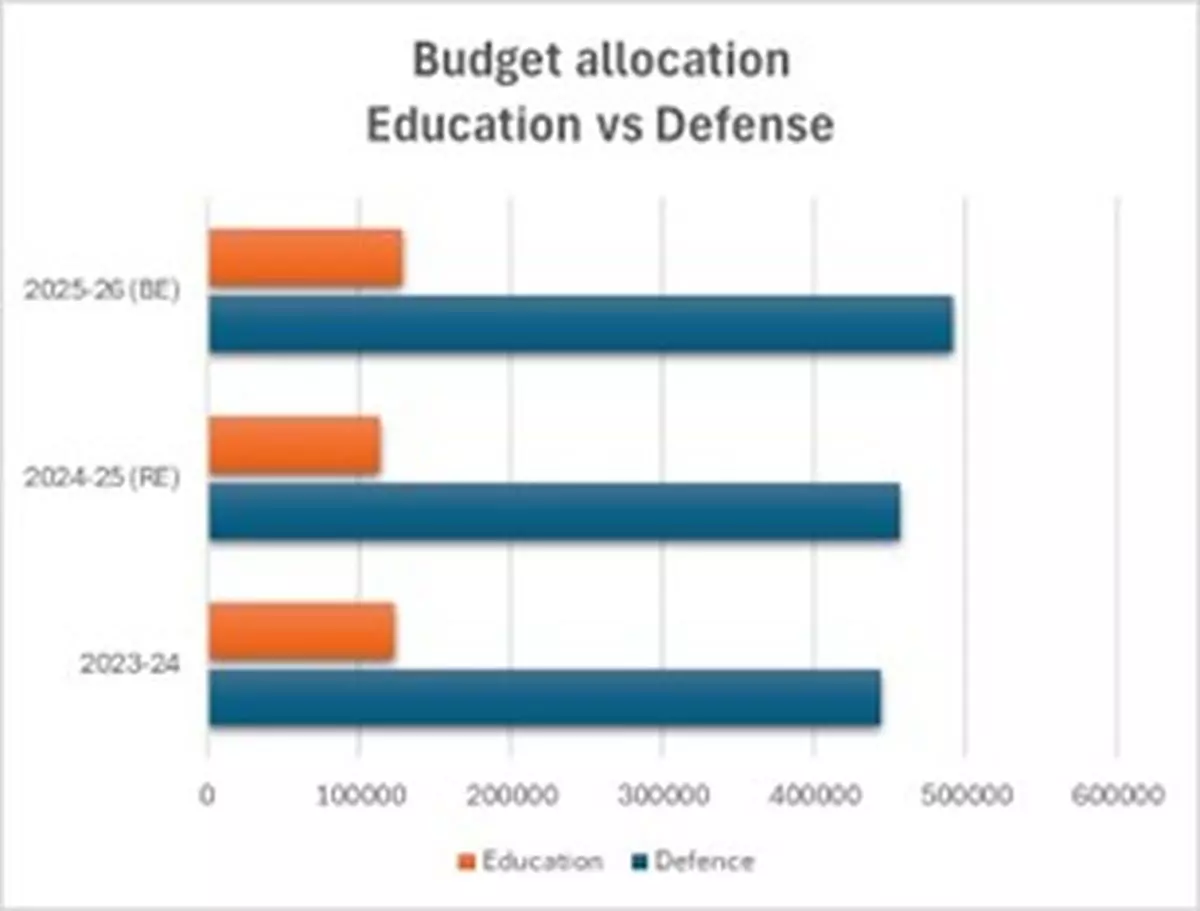

Budget allocation: Education vs Defence. (Source: Budget 2025-26)

While the government with the recent budget did try to boost initiatives such as Atal Tinkering Labs and digital connectivity programs, these attempts to modernise education is limited when the fundamental issues—lack of investment and inadequate teacher training—continue to remain unaddressed.

A comparison with the allocations for defence drives home the point that education simply is not a priority for this government (see graph above).

Healthcare: Rural-urban divide

Healthcare is in the same boat. While at first glance India’s healthcare budget appears to be improving—it is true that the allocation has increased from Rs.33,150 crore in 2015-16 to Rs.95,957 crore in 2025-26, a more than 100 per cent jump—dig deeper and the picture is far less reassuring.

Despite the increase, India’s hospital bed availability remains critically low, with just 1.4 beds per 1,000 people, far below the WHO recommendation of 3.5 per 1,000. Worse, government hospitals have an even more alarming ratio—only 0.79 beds per 1,000, meaning the country is short by 2.4 million beds. The doctor-to-patient ratio stands at 1:1,511, again failing to meet the WHO-recommended 1:1,000.

The rural-urban divide further exposes the cracks in the system. Seventy per cent of Indians live in rural areas, yet only 40 per cent of hospital beds are available to them. Nurse-to-patient ratios are at 1:670, a glaring shortfall from the recommended 1:300. Public hospitals are overwhelmed, underfunded, and stretched beyond their limits, while the better-equipped private hospitals are out of reach for millions due to their high costs.

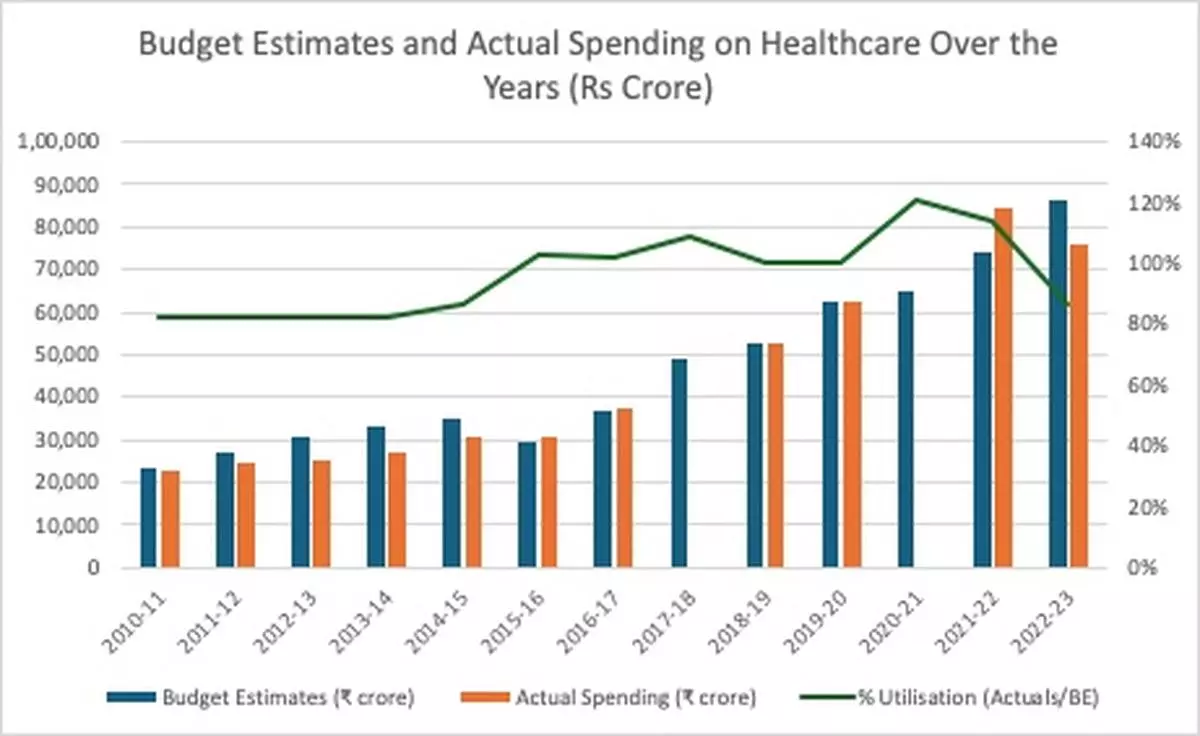

The graph below tells a troubling story, not only is the healthcaresector underfunded, but the government does not even fully utilise what it allocates. As seen in the graph, actual expenditure often falls short of budget estimates, highlighting deep structural gaps within the system. Whether due to bureaucratic inefficiencies, delays in project execution, or lack of long-term planning, the unspent funds reflect a widening disconnect between policy and implementation. Allocating money on paper means little if it fails to translate into real improvements. The consistent underutilisation raises a serious question.

Budget Estimates and Actual Spending on Healthcare over the years (in Rs. crore) (Source: CDPP)

Perhaps the most devastating statistic is this: 62.6 per cent of India’s total healthcare expenditure is paid out-of-pocket by individuals, one of the highest figures in the world. Medical bills are a leading cause of poverty in India, yet the government has done little to reduce this burden.

The key to escape the traps that loom over the future, from the middle-income trap to the risk of premature deindustrialisation or even jobless growth to what the economist Arvind Subramanian calls the danger of becoming a “stalling economy”, we must recognise that national power is not just measured in defence budgets and GDP figures. It is measured in the capabilities of its people.

Also Read | Budget 2025: The class project in full swing

With a young population, India has a fleeting window to reap the benefits of the demographic dividend, but without robust investments in education and healthcare, that advantage could easily turn into a demographic disaster. A McKinsey report warns that India risks “growing old before it grows rich”, as inadequate human capital investments stall economic progress.

No nation has ever achieved sustained prosperity without first ensuring that its people are healthy, skilled, and empowered. Until India ensures that every child has access to quality education and that no family fears medical bankruptcy, it cannot become a developed country.

Deepanshu Mohan is Professor of Economics and Dean, IDEAS, Office of InterDisciplinary Studies, and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), OP Jindal Global University. He is a visiting professor at the London School of Economics and currently a visiting fellow to the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department at the University of Oxford.

Ankur Singh, a Research Assistant with CNES, OP Jindal Global University, and a member of its InfoSphere team, and Anania Singhal, a Research Intern with the CNES, also contributed to this article’s research.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/economy/union-budget-2025-26-education-healthcare-expenditure-spending-viksit-bharat/article69187308.ece