In the late 1990s, Malayalam cinema entered an era of prudent prurience—when adult films starring C. Shakeela Begum aka Shakeela outperformed even the formidable box-office draws of megastars Mammootty and Mohanlal.

Shakeela did not conform to the conventional taxonomy of adult entertainment luminaries. She was neither a Jenna Jameson nor a Nina Hartley; she was certainly no Mia Khalifa or Sunny Leone. Compared with some of social media’s “only-fans” stars, with their boudoir aesthetics, Shakeela maintained a relatively demure sartorial presence. And yet she went on to become the undisputed sovereign of Kerala’s softcore cinema in the early 2000s.

Rated A: A Cultural History of Malayalam Soft-Porn

By Darshana Sreedhar Mini

Zubaan

Pages: 351

Price: Rs.695

The Shakeela phenomenon went beyond Kerala. The dubbed versions of her films in Tamil, Telugu, and Hindi, with obvious and clever additions of hardcore “bits”, broke box office records.

In more than one way, the rise of Shakeela, along with many of her clones, is a sociological study of the Malayali male psyche. Here was a demographic whose suppressed desires found vicarious manifestation in Shakeela’s performances. The revelation lay not in what she chose to display but in how the audience projected their fantasies onto her body. Shakeela played a neat trick: while revealing relatively little, she prompted her male audience to bare their own psyche.

However, save for a few essays in Malayalam mass media and a few quasi-academic articles, there have not been any comprehensive studies to understand Kerala’s complex relationship with porn. The story of how Malayali men consumed porn as literature, cinema, and in other media, beginning in the 1980s, peaking in the 1990s and 2000s and finally switching to Telegram, Twitter, and Reddit in the 2010s and 2020s, is the story of a voracious appetite and the generational exchange of frustration of a population that boasts the greatest literacy numbers and some of the best cultural practices in India.

Also Read | New trails of discovery

Rated A: A Cultural History of Malayalam Soft-Porn by Darshana Sreedhar Mini is an interesting window into this peculiar corner of Indian cinema. This is Sreedhar Mini’s first book and is based on her doctoral thesis. The title might prompt one to expect a titillating footnote in film history, but what unfolds is far more intellectually provocative.

Sreedhar Mini, an assistant professor of film at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is also the co-editor of South Asian Pornographies: Vernacular Formations of the Permissible and the Obscene. The book draws from her decade-long research involving fieldwork, archival research, and interviews with film industry personnel.

Much like Elena Gorfinkel’s Lewd Looks: American Sexploitation Cinema in the 1960s and Cut-Pieces: Celluloid Obscenity and Popular Cinema in Bangladesh by Lotte Hoek, Sreedhar Mini approaches her subject with rigour to examine how this culturally specific form of erotica operated within the networks of labour, censorship, and transnational circulation. Her analysis sheds light on broader questions of gender, class, and regional identity in South Asian media.

Sreedhar Mini explores how these films created their own economic ecosystem, operating in the liminal spaces between legitimate cinema and outright pornography. The industry’s reliance on pseudonymous credits and informal distribution networks speaks to an almost theatrical performance of respectability politics—neither fully underground nor entirely above board.

Malayalam cinema’s madakaranis

The phenomenon of the madakarani (or sex siren, a label used for Shakeela at her peak, like many others) emerges as a particularly rich site of cultural contradiction. These actresses occupied a peculiar position of simultaneous hypervisibility and social marginalisation. In the process, their bodies became contested territories where questions of female agency, regional identity, and class mobility played out in fascinating ways.

What elevates Sreedhar Mini’s work beyond mere cultural anthropology is her keen attention to how this regional soft-porn wave reflected and refracted larger tensions in Kerala society between tradition and modernity, the local and the global, between restrictive morality and liberating expression. The industry’s eventual decline in the 2000s thus reads less as moral comeuppance than as the inevitable resolution of particular historical and economic forces.

One comes away with the distinct impression that Kerala’s soft-porn moment, for all its apparent prurience, offered a unique lens through which to examine the contradictions of Indian modernity itself. On that cue, Mini has produced that rarest of academic works—one that takes its unconventional subject matter seriously while never losing sight of the human stories at its heart.

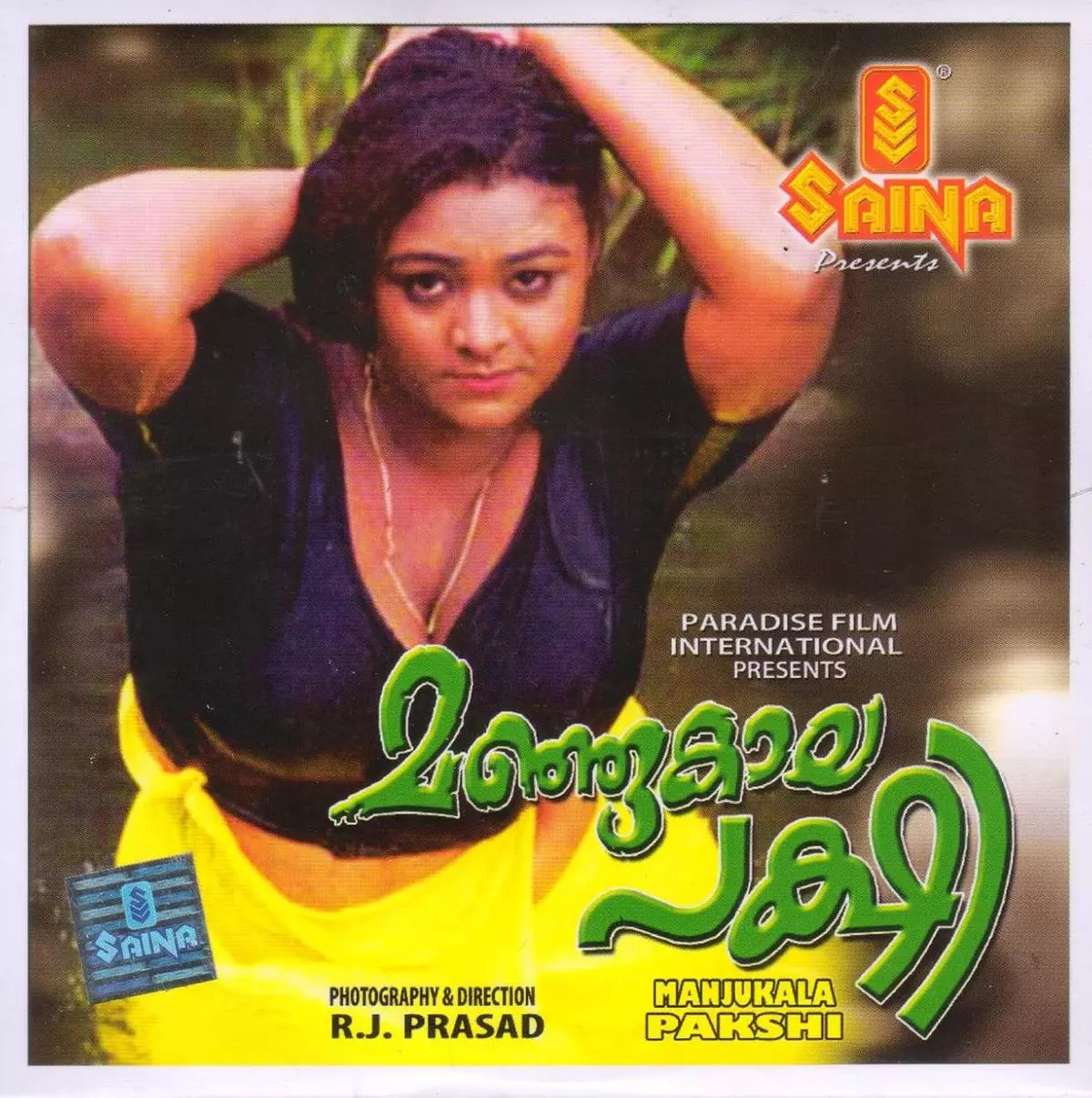

Shakeela on the poster of the Malayalam film Manju Kala Pakshi (2000). In more than one way, the rise of Shakeela, along with many of her clones, is a sociological study of the Malayali male psyche.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Three particularly striking anecdotes from Mini’s scholarly excavation illustrate just how remarkable this cultural moment was.

At the Murugan Temple at Vadapalani in Chennai, Mini writes, distributors engage in an unusual ritual: marking their soft-porn film cans with sandalwood paste and offering the first print to the deity for blessings. Even non-Hindu producers were persuaded to follow this practice by distributors. One production manager memorably observes: “Film production is a gamble at the end of the day. So, even though I am an agnostic, I would not mind doing a puja at the Murugan Temple before sending the cans to the theatres.”

Mini also talks about the system of pseudonymous credits, and how entire production crews operated under fictional names. Some directors became known by fabricated monikers. This reviewer remembers Saj-a-Jaan, who created sensational softcore films like Love in the early 2000s. The practice became so endemic that when the real names of the directors appeared in the credits, audiences assumed that those, too, were fictional.

Arguably, the most shocking and bizarre revelation concerns the fate of some soft-porn cinema theatres: they were converted into churches. The book specifically mentions one such establishment in Wayanad that underwent this transformation from the temple of earthly desires to a house of spiritual salvation. More intriguing still is the account of a priest who reported hearing mysterious moans and sounds from the building’s previous incarnation—creating what one might call a rather unique intersection of the sacred and the profane. This story appears in the film Kanyaka Talkies (Virgin Talkies), which explores the conversion of a soft-porn cinema theatre into a church. The film follows Father Michael, who is tasked with motivating believers to strengthen their faith after a soft-porn cinema theatre called Kanyaka Talkies is converted into a church.

These anecdotes also spotlight the larger contradictions of Kerala’s relationship with its soft-porn industry. Evidently, this relationship is marked by equal parts moral panic and pragmatic acceptance. And this is played out against a backdrop of religious devotion and commercial enterprise.

Suggestions, concerns

While Sreedhar Mini’s work is an impressive contribution to the field, there are areas where the scholarly appetite remains somewhat unsated.

Cover of Rated A: A Cultural History of Malayalam Soft-Porn by Darshana Sreedhar Mini.

Firstly, there is the matter of primary sources. While the book admirably excavates institutional archives and media coverage, it is noticeably reticent in engaging with the actual consumers of these films. The absence of substantive interviews with the period’s viewing public—those men who queued up at Kerala’s B-circuit cinemas with religious devotion—leaves a gap in our understanding. To her credit, that is not the primary focus of her research, but one believes it would have added more value.

Secondly, there is a somewhat metropolitan bias in the source material. One suspects that the true story of Malayalam soft-porn lies not in well-documented urban centres but in the provincial theatres and rural screening rooms where these films truly found their audience. The book’s reliance on readily available urban narratives may overlook such regional variations in reception and consumption.

Thirdly—and here one treads delicately—there is the matter of class analysis. While the book acknowledges class dynamics, one yearns for a deeper investigation of how these films were received across different social strata. The middle-class moral panic is well-documented, but what of the working-class viewers who formed the backbone of this industry’s success?

Moreover, the book occasionally falls into the “web archive trap”—the modern tendency to privilege digitally accessible sources over more challenging but potentially more revealing primary materials. Contemporary online discourse about Malayalam soft-porn, while interesting and varied, cannot fully illustrate the historical moment of its actual consumption.

Also Read | LSD 2: Looking sin in the eye

One might also suggest that a more robust comparative framework would have enriched the study. How did Kerala’s soft-porn industry differ from similar phenomena in Tamil Nadu or Bangladesh? A detailed contextual analysis might have situated the phenomenon within broader South Asian cultural currents. But of course, it would compromise the book’s current sleek form of about 200 pages. But I feel the uniqueness of the subject, and given the fact that not many researchers would pick up such a topic, demands such extensive investigation.

That said, these critiques should be understood less as fatal flaws than as invitations for future scholarship. Sreedhar Mini has, after all, done the valuable service of making this curious cultural moment academically respectable—no mean feat when dealing with material many scholars might have dismissed as unworthy of serious consideration.

Perhaps the greatest compliment one can pay this work is that it leaves one wanting more, rather like the subject matter itself.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/books/review-rated-a-cultural-history-darshana-sreedhar-mini-malayalam-softcore-cinema-shakeela-adult-films-kerala/article69199353.ece