Faron Vincent, five years ago when she was twelve, had become a legend, “a living saint” when she liberated her people of the island nation from a dragon-riding colonising empire. All by being a host to the gods of San Irie, being a medium for their powers and using it as a weapon to be wielded in the service of the nation—which she did when fighting against the humongous fire-wielding creatures, the dragons. But now, with the battle left behind and the victory rejoiced, she uses her power to win bets or trivial things, and be a troublemaker, widely contrasting to the image of a ‘holy child’ she has been burdened with.

It is this post-war, post-revolution, and recent liberation that first pulls the reader into the world. The height of danger is clear from the dragons, despite the powerful drakes and Faron, the Childe Empyrean, “an internationally recognisable symbol of divine retribution”. But it’s the aftermath of years of colonisation and the collective strength that a revolutionary struggle demands that establishes San Irie as a small nation facing a post-war wrestle, entangled in deeper politics. And this sets a heavier weight on Faron’s ability, pushing her to an exploration of her purpose.

This post may contain affiliate links.

The focus on war, especially one fought with a colonising power, shows both a brutal present and a shaken aftermath through frequent remembrance of the war Iryans fought five years ago (”Dragons would often burst over the peaks flame-first, killing the land with their blazing breath and blowing wooden shacks across the plains with their wings.”) or the reminders still visible: “blackened patches of land that had been ravaged by dragonfire, charred soil that could never again yield new life”.

In addition, it explores the emotional trauma ingrained in a once-colonised populace, and also presents a poignant look into the sharp gravel of colonised bridges through the son of the current ruler of the Langlish Empire, Reeve. His decision, five years ago, to side with San Irie carries a significant arc that intrigues throughout and gives way to a certain tension between him and Faron.

Her older sister, Elara Vincent, had followed her little sister into the war but is growing to despise the shadow of her renowned sister, often endlessly teased by Faron for being docile. Now, at eighteen, she’s determined to become a soldier in the Iryan Military Forces by proving her skill of ‘combat summoning’: calling on an ancestral spirit to be supported in a fight, and testing to be a Drake pilot, a revered soldier who bonds with a semisentient giant flying metal war machine, only if the Drake chooses the pilot too.

Their different pathways and outlooks are merged again when Queen Aveline —a young leader who had taken the shattered country to war at just sixteen years of age— after five years of liberation and the debilitating resources, decides to go down a diplomatic path: organising a peace summit to host neighbouring nations, including the colonial empire, the Langlish. The Queen needs both the sisters to be on the port, alongside her, as a relief to the island’s population worried with the presence of the giant being, the dragons, seated at the shore due to the Langlish Empire’s arrival.

But when Elara bonds with a Langlish dragon, linked intricately enough to feel everything that happens to the dragon and thereby leaving her sister and other soldiers powerless as the dragons flies around, an undercurrent begins, diverging the destinies of the sisters. The many lingering effects of colonialism is hard to miss, from the oppressor’s language to the lack of respect for traditional strengths of colonised nations: “Langley has never understood or respected San Irie’s magic or its gods.” It is this magic that opens doors to someone revered as a god, someone who had taught the founders of the Langlish Empire how to bond with dragons and ride them.

Cole lets you be intrigued, as political power plays fuelled by the insidious nature of colonial empires unravel, a “Chosen One” slowly loses faith in herself, and an older sister who “wanted to matter, too” finally gets a miracle of her own but must step off San Irie and into the Langlish lands to train as a dragon co-rider. And Cole does this while painting a queernormative world with grandiose mythology and striking, rich details.

Whether it’s Faron’s summoning abilities as she “skimmed the contours of the dragon’s soul, and it felt as if she’d leashed herself to a comet” or surprisingly alluring scenes like a dragon “nuzzling its scaled head against the drake’s metal one” to display a startling affection, “an olive branch of peace”. The extensive detailing wonderfully extends to the characters, conjuring vivid paths for all yet entangling their destinies with precision. At the end, So Let Them Burn will feel otherworldly and enormous, just like its dragons.

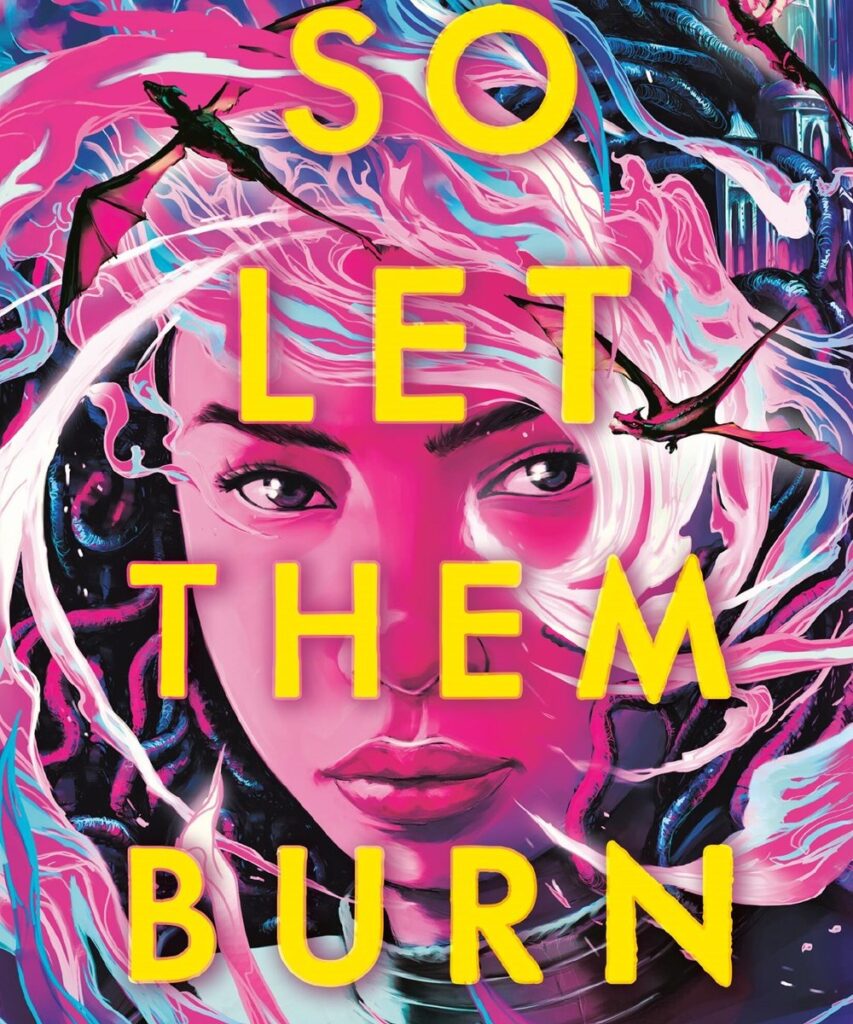

So Let Them Burn, Kamilah Cole

Little, Brown Young Readers, Jan 2024

Note: A review copy was acquired via the publicist.