The Need for a Decent Pension Scheme for the Elderly

In article 3 of this budget analysis series published earlier in Janata Weekly, we have given extensive data regarding the grim poverty situation in the country. The data show that at least 60–70 percent of the country’s population is living on the edges of destitution.

The worst sufferers of this poverty crisis are the elderly, those above the age of 60. The majority of them would have worked in informal sector jobs during their younger days. Most of these jobs involve doing very hard, back-breaking work. By the time these workers stop working because of old age, their bodies are broken and they suffer from many diseases. Most of them do not have any pension or savings on which they can live a life of dignity in their old age. According to the India Ageing Report 2023, there are presently 14.9 crore people aged 60 years or above in India, representing 10.5 percent of the population. The report estimates that 40 percent of India’s elderly population are in the poorest quintile, with 18.7 percent living without income.[1]

The least the government can do for the elderly is: i) provide them a decent old age pension; ii) provide them universal and free health care facilities — not just hospitalisation but free outpatient facilities. We have discussed the dismal state of out public health services in a previous article published in Janata Weekly. This article discusses the Modi Government’s budgetary allocations for pension schemes for the poor.

National Social Assistance Programme

In her budget speeches, FM Nirmala Sitharaman has repeatedly claimed that the Modi Government has sought to ensure social inclusivity and growth for every strata through its commitment to alleviating social and financial vulnerability. An important element of fulfilling this commitment, especially to elderly people, is providing people social security in their old age.

In India, the main programme of the Central Government for providing social security to the poor and especially those working in the unorganised sector is the National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP). This umbrella programme has several schemes that provide non-contributory income security to the elderly, women in distress (widowed, abandoned, single women, etc.) and persons with disabilities in the below poverty line (BPL) category. The four main sub-schemes under NSAP are:

- Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS);

- Indira Gandhi National Widow Pension Scheme (IGNWPS);

- Indira Gandhi National Disability Pension Scheme (IGNDPS); and

- National Family Benefit Scheme (NFBS)

The NSAP also includes the Annapoorna scheme, under which 10 kg of foodgrains per month are provided free of cost to those senior citizens who, though eligible, are not receiving old age pension. The allocation for this is negligible, just around 10 crore, and even this is not spent (in 2022–23 Actuals and 2023–24 RE, the expenditure is zero), so we are not discussing it here.

The NSAP is implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development. The details of the four schemes under it are given in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1: NSAP Sub-Schemes, Eligibility Criteria and Central Assistance

| Sub-scheme | Eligibility Criteria | Central Assistance |

| Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS) | BPL category person who has attained the age of 60 yrs | Rs. 200 per month (60–79 yrs)Rs. 500 per month (80 yrs & above) |

| Indira Gandhi National Widow Pension Scheme (IGNWPS) | Widow belonging to BPL category who has attained the age of 40 yrs | Rs. 300 per month (40–79 yrs)Rs. 500 per month (above 80 yrs ) |

| Indira Gandhi National Disability Pension Scheme (IGNDPS) | Disabled person (with 80% disability) belonging to BPL category above age of 18 yrs | Rs. 300 per month (18–79 yrs)Rs. 500 per month (above 80 yrs ) |

| National Family Benefit Scheme (NFBS) | In case of death of the primary breadwinner between 18–59 years of age in a BPL category family | Rs. 20,000 as one-time assistance |

The amounts given in Table 13.1 — from Rs. 200 per month to a maximum of Rs. 500 per month for those of age 80 years and above — are shamefully low amounts. The pension amounts have not been revised for more than a decade. The last revision was made in 2011, when the pension for people above 80 years was increased to Rs. 500 (in the three pension schemes above). The pension for people in the age group 60–79 years (under IGNOAPS) has not been revised since 2007.

The CAG’s 2023 performance audit of the NSAP refers to four separate reports of the Standing Committee on Rural Development that repeatedly “expressed concern on the meagre amount and strongly recommended to increase the amount of assistance under NSAP.” The audit report goes on to say: “Department of Rural Development vide its reply to the Committee informed its inability in carrying out revision in the Scheme in the wake of decision taken at the highest levels in Government to continue with the existing system.”[2] It is an extremely stony-hearted government in power at the Centre.

Central Allocations for NSAP

NSAP provides pensions to only those living below the poverty line — which itself is shamefully low as discussed in article 3 of this budget analysis series published earlier in Janata Weekly. So, as it is, a very large number of poor are excluded from those classified by the government as BPL families. The Modi Government has used a simple tactic to further reduce the number of BPL families being covered under NSAP. It has capped the number of people to be covered under this scheme by applying the state-wise Below Poverty Level estimates to the population figures as per the 2001 Census.[3] Yes, the 2001 census — this is not a typo. The total number of elderly BPL people in the country as per the 2001 Census was 3.19 crore. This is the maximum number of elderly people in the country to whom the Centre provides pensions under NSAP.[4]

Chapter II of the Program Guidelines of NSAP is titled “Salient Features of Schemes of NSAP”. It says that the “Key Principles” of the scheme are “non-negotiable features, based on the Constitutional provision”, and goes on to say that one of the key principles is “Universal coverage of eligible persons and pro-active identification”.[5] The Centre, by deliberately capping the number of eligible beneficiaries of NSAP as per the 2001 Census, is making a mockery of this promise.

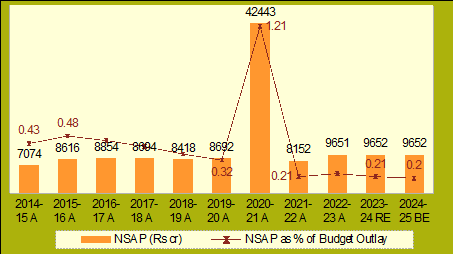

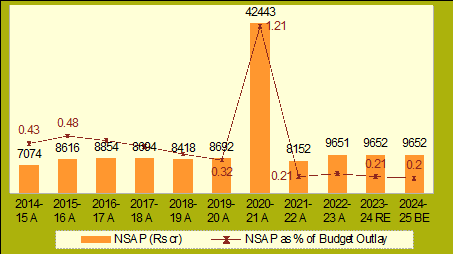

By such duplicitous means, the Centre has managed to keep its allocations for NSAP very low. We give the total allocation for the NSAP during the past 10 years of Modi rule in Chart 13.1. As the chart shows, the Modi Government has kept the budgetary allocation for the NSAP at the scandalously low level of less than Rs. 10,000 crore per year during the past 10 years it has been in power! The only year it made an exception was 2020–21, the pandemic year, that had catastrophic consequences for the people because of the Centre’s callous handling. The pandemic pushed an additional crores of people below the poverty line. The Modi Government initially sought to ride out the pandemic with empty slogans. Subsequently, it released a very inadequate relief package, which was accompanied by a lot of bluster. One of the components of this package was a direct transfer of Rs. 1,500 to all women account holders of Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (a total of 20 crore women). Consequently, the revised estimates for 2020–21 show a jump in the total allocation for NSAP to Rs. 42,443 crore (Chart 13.1). But the very next year (2021–22), despite the fact that the unorganised sector that provides employment to more than 90 percent of the population continued to be in crisis, the Modi Government slashed the spending on this scheme to less than 2019–20 A. Since then, the allocation has seen only a marginal increase in nominal terms.

Chart 13.1: Budget for National Social Assistance Programme, FY15–F25 (Rs. crore)

A better idea of the Modi Government’s prioritisation of NSAP can be had by computing the spending on this program as a percentage of the total budget outlay. The reduction in the allocation in the post-pandemic years is so steep that it is less than the pre-pandemic levels. This year, the allocation as a percentage of the budget outlay has fallen to less than half of 2014–15 — from a tiny 0.43 percent in 2014–15 A, it has come down to 0.2 percent this year.

Increased fiscal burden on states

In 2016, the Central Government took the decision to make NSAP a ‘Core of Core’ scheme, that by definition means that the Centre undertook to fund 100 percent of the requirement for the scheme. However, the allocations of the Centre are so miserly that the States are forced to allocate substantial sums for the scheme.

According to the CAG report mentioned above, 33 States and Union territories implement their own State-level schemes, in addition to the Central NSAP. State schemes serve two purposes:

- to top-up the pension amount because the central contribution is measly. The top-ups range from Rs. 150–200 (in Chhattisgarh and Bihar) to Rs. 2,300 (in Haryana and Andhra Pradesh).

- several States give pensions to additional categories of pensioners to whom the entire pension is given by the State, with no Central contribution. These include categories such as agricultural workers, toddy tappers, etc.[6]

The CAG report says that during the three years 2017–18 to 2019–20, the Modi Government allocated Rs. 26,623 crore for NSAP. The States and UTs spent an additional Rs. 82,836 crore — three times the allocation of the Centre — for the State pension schemes (see Table 13.2).[7]

Table 13.2: NSAP: Centre and State Allocations and Beneficiaries, FY18 –FY20

| Total Financial Allocation | Average No. of Beneficiaries / year | |

| Centre | Rs. 26,623 crore | 2.83 crore |

| Additional Funds Provided by States and Additional Beneficiaries Covered | Rs. 82,836 crore | 1.73 crore |

Data compiled by independent researcher Karuna Muthiah suggests that the total number of beneficiaries of all the pension schemes in the country is more than that estimated by the CAG report and is around 8 crore. This means that the States provide pension benefits to an additional 5.2 crore people, and not 1.7 crore as mentioned in the CAG report.[8]

So, despite being a ‘Core of Core’ scheme, whose entire responsibility should be borne by the Centre, the Centre is spending only 25 percent of the total spending on this scheme, and is providing benefits to only 35 percent of the total beneficiaries of the scheme; the States are funding the remaining 75 percent, and providing benefits to two-thirds of the beneficiaries left out of the Centre’s coverage.

The PMSMY Jumla

Because of the tiny allocation for NSAP, activists and unions have been agitating for a decent old age pension for the aged for years. Apparently ceding to their demand, in his interim budget speech just before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the finance minister announced a new pension scheme for informal sector workers, pompously labelled as Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maandhan (PMSYM), wherein informal sector workers would be given a monthly pension of Rs. 3,000. The FM stated: “It is expected that at least 10 crore labourers and workers in the unorganised sector will avail the benefit of ‘Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maandhan’ within next five years making it one of the largest pension schemes of the world.”

The announcement created a big splash in the media (as desired!). A closer look reveals that the new scheme is a cruel joke on informal sector workers. It is a bigger hoax than the Ayushman Bharat health insurance scheme. Nevertheless, the Modi bhakt media went to town touting it as the largest pension scheme in the world!

Under the PMSYM scheme, workers in the age-group of 18 to 59 years are not going to automatically get a pension of Rs. 3,000 per month upon attaining the age of 60. They will get this pension only after paying a monthly premium for several years, the amount of which will depend upon the duration for which they pay this premium. For instance, a worker who starts paying at the age of 29 would have to pay Rs. 100 per month for 31 years and a worker who starts paying at the age of 18 would have to pay Rs. 55 for 42 years. The government would make a matching contribution. Only then will the worker, on reaching the age of 60 years, get a pension of Rs. 3,000 per month.[9]

The PMSYM scheme only reveals how cut off are PM Modi and his cabinet ministers from the real life conditions of our country’s informal sector workers (even though PM Modi may claim to be a chaiwallah in his younger days). The wages of the unorganised workers are so low, their jobs are so uncertain, their life conditions are so precarious, that asking them to first pay a defined, even though small, part of their hard earned income every month on a scheme from which benefits will flow after 20 / 30 / 40 years is completely unrealistic. Governments have in the past broken so many promises, denied so many promised benefits, to ordinary people on vague excuses that expecting workers to believe the government promise that it would pay them a pension if they deposit some amount for 2–4 decades years is silly, to say the least.

Secondly, the pension is a pittance. For a worker aged 30 today, they will be getting a pension of Rs. 3,000 after 30 years. Even if we take an average annual inflation of 5 percent, the real value of this would be a mere Rs. 700 after 30 years (as compared to today)!

But the biggest problem with this pension scheme is that the pension benefits are supposed to start when the workers reach the age of 60. Unfortunately, a majority of workers will not be alive to benefit from it! While an age of 60 years is good for giving post-retirement benefits to the middle classes, it is completely unrealistic for hard working informal sector workers. Studies show that life expectancy among poor scheduled tribes is only 56.9 years, and for poor scheduled castes is 63 years. This means that life expectancy for informal sector workers would not be more than 60 years; and life expectancy for informal workers doing the hardest jobs, like construction workers and quarry workers, would be even lower than this.[10]

Clearly, the PMSYM was only a 2019 Lok Sabha election jumla. Therefore, it is not surprising that the scheme has failed. PMSYM was to potentially cover 42 crore unorganised sector workers. According to a press release of the Ministry of Labour and Employment, as of 2022–23, the total number of workers who had registered under this scheme was only 49 lakh, or just 1.2 percent of the 42 crore potential beneficiaries, even after five years since its launch.[11]

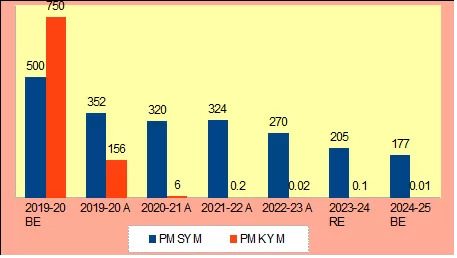

With unorganised sector workers showing no interest in the scheme, the FM has also completely forgotten about it. The budget allocation for this scheme has dwindled from Rs. 500 crore in 2019–20 BE to Rs. 353 crore in 2019–20 Actuals to Rs. 177 crore in this year’s BE — a reduction of 65 percent in nominal terms (see Chart 13.2).

Chart 13.2: Budget for PMSYM and PMKYM, FY20–FY25 (Rs. crore)

Pradhan Mantri Karam Yogi Maandhan

Four months after the launch of PMSYM, the new Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in her maiden budget speech in July 2019 announced another pension scheme named as Pradhan Mantri Karam Yogi Maandhan (PMKYM) for the three crore retail traders and small shopkeepers in the country whose annual turnover is less than Rs. 1.5 crore. She pledged to spend Rs. 750 crore in the first year of the scheme that promised a monthly pension of Rs. 3,000.

The details of this scheme are exactly the same as that of PMSYM. Traders and retailers will not automatically get a pension of Rs. 3,000 on reaching the age of 60. Like the PMSYM, the PMKYM is also a contributory scheme, in which the beneficiaries will get a pension only after paying a monthly premium for several years; the Central government will provide a matching contribution. Thus, a trader who starts paying at the age of 18 would have to pay Rs. 55 for 42 years. On reaching the age of 60 years, she will then get a pension of Rs. 3,000 per month.

The pension is a pittance, and so this scheme has turned out to be an even bigger failure than the PMSYM. In its first year itself, the actual spending on the scheme came down from the allocated Rs. 750 crore to Rs. 155.9 crore. The next year, the actual spending plummeted to Rs. 6 crore, and in 2022–23, it came down to Rs. 2 lakh. This year, the scheme has been allocated Rs. 1 lakh (see Chart 13.2). The allocation has fallen to such a tiny level because as per official data, the scheme had just over 50,000 takers till January 2023.[12]

To Conclude

So, this is Modinomics. It is essentially free market neoliberalism — if you are rich and have money, you have the freedom to make more money by manipulating people’s choices, or by profiting from manufactured addiction, or by indulging in market manipulation and speculation, or by profiting from sickness and misery and illness of people, or by selling weapons of mass destruction, or by making profits from so many other such freedoms that neoliberalism has opened up for the rich; but, if you are poor and don’t have money, you have the free market freedom of dying because of lack of affordable healthcare, or dying because of hunger, or dying because of extreme cold or heat waves, or dying because of no savings and no pensions in old age …

Notes

1. India Ageing Report 2023, p. 50, International Institute for Population Sciences and United Nations Population Fund, https://india.unfpa.org.

2. “Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Performance Audit of National Social Assistance Programme”, p. 16, Report No. 10 of 2023, https://cag.gov.in.

3. “NSAP_Guidelines_Oct2014”, https://nsap.nic.in.

4. Reetika Khera, “Lifeline for Crores of Elderly, But Ignored by the Centre, the NSAP Is a Pension Scheme of Delays”, 12 May 2024, https://thewire.in.

5. “NSAP_Guidelines_Oct2014”, p. 4. op. cit.

6. For details of the State pension schemes, see: Reetika Khera, “Lifeline for Crores of Elderly, But Ignored by the Centre, the NSAP Is a Pension Scheme of Delays”, op. cit.

7. The CAG report actually gives data for four years — 2017–18 to 2020–21. But its 2020–21 data excludes the additional relief given during the corona pandemic, which does not come under the sub-head IGNOAPS, but is under the head “DBT to PMJDY Women Account Holders” in the budget papers. So we have given data only for the first 3 years. Also note that the CAG data for the first three years does not match the data given in the Union Budget figures given in Chart 13.1.

8. Reetika Khera, “Lifeline for Crores of Elderly, But Ignored by the Centre, the NSAP Is a Pension Scheme of Delays”, op. cit.

9. B. Sivaraman, “Interim Budget’s Pension Scheme Is a Big Hoax”, 7 February 2019, https://www.nationalheraldindia.com.

10. Sudhir Katiyar, “Budget 2019: Pension Scheme for Unorganised Workers Is Yet Another Illusion”, 2 February 2019, https://thewire.in.

11. Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-Dhan (PM-SYM) Scheme to Provide Old Age Pension to Unorganized Sector Workers, Ministry of Labour & Employment, 23 March 2023, https://pib.gov.in.

12. Navya Asopa & Shreegireesh Jalihal, “Billboard Governance: Under Modi, Majority of 906 Schemes Faced Funding Squeeze”, 27 May 2024, https://www.reporters-collective.in.

(Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.)