Byline: Umesh Isalkar

Poonam was relieved when MRI and PET scans confirmed her endometrial cancer was in the early, manageable Stage 1. A Kanpur resident, she travelled all the way to Pune for what was supposed to be a routine hysterectomy. But during surgery, a sentinel node (the first lymph node where a cancer is likely to spread) procedure using a fluorescent dye revealed three tiny cancerous lymph nodes that conventional imaging had left undetected. They were promptly removed, and a follow-up radiotherapy course done. A year later, Poonam remains cancer-free. Sheela from Haryana wasn’t so lucky. The absence of the dye technique had led surgeons to indiscriminately remove lymph nodes in her case. But they missed critical ones, leading to a recurrence in an overlooked area.

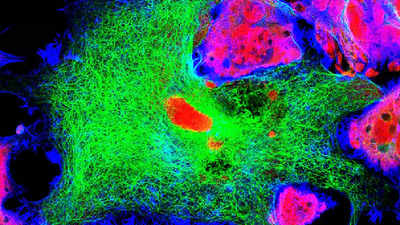

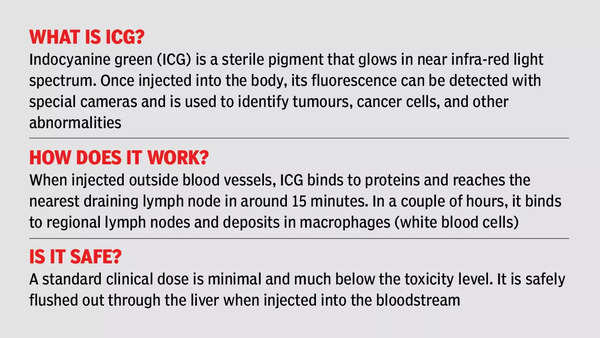

The fluorescent dye, called Indocyanine Green (ICG), has revolutionised onco surgeries across the world, particularly for breast, colorectal and oesophageal cancers. Advanced cancer centres in India equipped with laparoscopy and robotic systems frequently use ICG technology to detect these cancers. “Before ICG, we often removed lymph nodes closest to the tumour assuming they were cancerous, which led to high recurrence rates. But this technology allows us to precisely target and remove only the affected nodes, drastically reducing recurrence, unnecessary surgeries and improving survival rates,” says Pune-based robotic onco surgeon Dr Shailesh Puntambekar, the first to be credited with successful womb transplants in India. And the dye costs only Rs 1,200 per patient, making it highly cost-effective, he adds.

A 2020 meta-analysis published in The Lancet Oncology reported that sentinel node biopsies using ICG reduced cancer recurrence rates by 30% compared to traditional methods. Another study by the US National Cancer Institute found early-stage breast cancer survival rates to jump from 75% to over 92% with the adoption of ICG.

Why then is this cutting-edge technology yet to find widespread use for uterine and endometrial cancer surgeries in India? Doctors cite several logistical hurdles. “The uterus is internally located and requires a per vaginal (through the vagina) injection of ICG before surgery, which poses practical difficulties for surgeons. Centres performing robotic-assisted hysterectomies find it easier to use this technology, but traditional surgical approaches are less conducive,” explains cancer surgeon Dr Rudra Prasad Acharya, secretary of the Indian Association of Surgical Oncology.

Experts also point out that nearly 80% of endometrial cancer procedures in India are open surgeries, often involving extensive lymph node removal, which also yields higher surgical fees and greater professional satisfaction for some surgeons. Besides, detecting the dye in open surgeries requires a specialised ‘spy’ camera that costs a prohibitive Rs 25 lakh.

Not just that, there are only about 7,500 gynaecological surgeons trained in laparoscopic surgery, compared to 45,000 who only perform open surgeries. But adopting ICG technology is not a steep learning curve, says Dr Acharya. “Surgeons can become proficient after observing a handful of cases and performing guided procedures.” Also, he says the ICG dye is more readily available now, making it a routine tool in many cancer centres for breast, colorectal and oesophageal surgeries. So, using it for uterine cancers shouldn’t be a problem.

Uterine and endometrial cancers predominantly affect women aged 50 and above. According to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), both these cancers are on the rise, with over 1.75 lakh new cases reported annually. “Sentinel node mapping with ICG should be a standard part of surgical protocol, especially for early-stage uterine and endometrial cancers. The benefits far outweigh the challenges. It’s not just about sophistication in technology but also about improving survival rates and reducing unnecessary surgical interventions. We need a paradigm shift in outlook, where patient outcomes take precedence over procedural preferences,” says Dr Puntambekar, recalling dramatic improvements in patient recovery when using this approach.

Pioneering work at Hyderabad’s Basavatarakam Indo American Cancer Hospital and the Aster Group in Bengaluru has shown the clinical advantages of ICG. AIIMS Delhi has also published data on its routine use. But many cancer centres in India are yet to embrace it fully, rues Dr Acharya. “The shift is essential, given that 90% of India’s 1.75 lakh annual endometrial cancer cases are diagnosed in Stage 1. Expanding the use of ICG technology could greatly improve patient outcomes and reduce unnecessary surgeries,” says gynaecologist and laparoscopic surgeon Dr Sunita Tandulwadkar, national president of the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India.

Quote: This technology allows us to precisely target and remove only the affected lymph nodes, drastically reducing recurrence, unnecessary surgeries and improving survival rates

Dr Shailesh Puntambekar, Pune-based robotic onco surgeon