Zindagi Zindagi is my ideal type of social drama: one in which the societal issue at hand threads ineluctably through our characters’ personal journeys. Although, in an overarching sense, this film is “about” caste, each individual moment is simply about a person. Neither do the human stories that welcome you into this narrative world feel underdeveloped, nor are the structural inequities the film critiques depicted other than with the seriousness they demand. Perhaps yet more rarely–and despite its being both a social drama and an ensemble piece–this quiet, beautiful film also features a breathtaking central romance. Zindagi Zindagi was produced by Nariman A. Irani and A. P. Sharma and distributed by Jan Pictures. Story, screenplay, and direction are all by Tapan Sinha; Khwaja Ahmed Abbas wrote the nicely chewy dialogues.

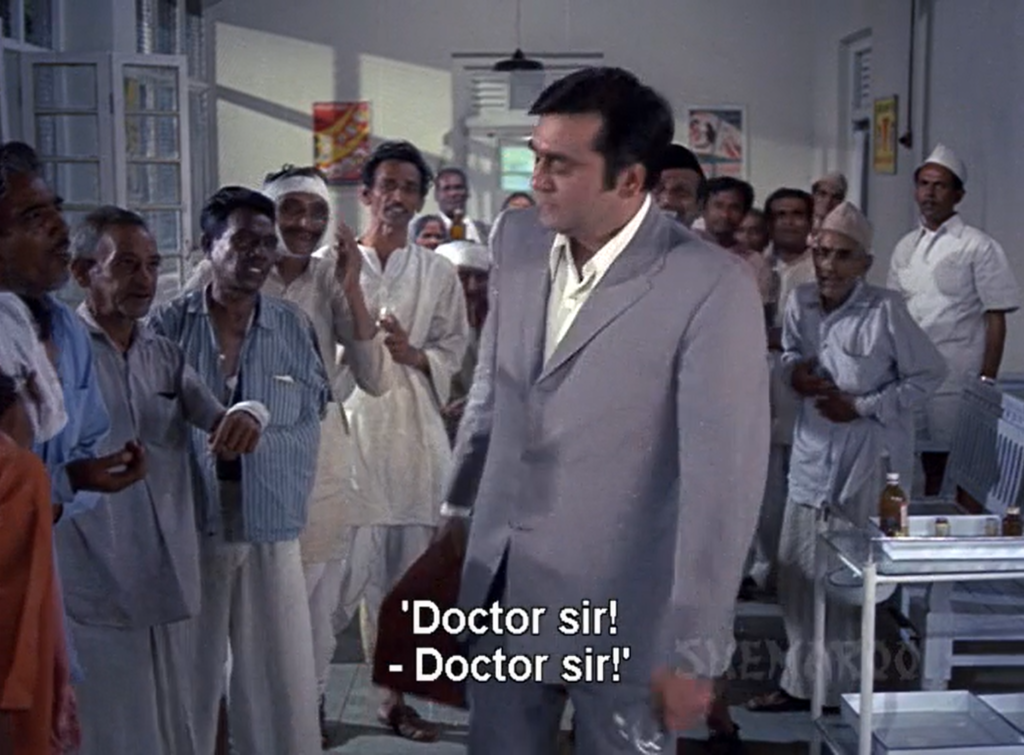

Despite a propitious academic background, Dr. Sunil (Sunil Dutt) has in middle age risen to no greater status than that of a rural doctor sahib. He, as the only physician at Ashanagar’s underfunded, essentially unsupplied hospital, must mollify a clamorous ward of convalescents with no more than “sweet words and bitter quinine.” The hospital’s social atmosphere has recently reshaped itself around Choudhary Ramprasad (Ashok Kumar), a current cardiac inpatient and erstwhile union board president. Ramprasad holds court from the open ward, which he just cannot stop reminding people he paid to have built; outside, his less patrician, less principled son Shiv Prasad (Ramesh Deo) is mustering the reelection campaign. It is to this barely functional facility that widow Meeta (Waheeda Rehman), on the basis of a long-ago acquaintance with Dr. Sunil, comes to seek treatment for her crippled son Babu (Master Tito). Meeta and child quickly settle in as semi-permanent houseguests of Dr. Sunil’s–ignominious appearances be damned.

In Zindagi Zindagi, pain does not purify. We might admire our characters when they make a personal sacrifice in deference to some larger good, but that suffering does not hold the inherent merit another breed of social issue film might accord it. In the slowly unfolding backstory segments, we see Meeta and Dr. Sunil make honest but uncomfortable homes for themselves within situations they were not entirely free to choose: her to support her child independent of her exploitative extended family, him to provide a humane public voice and some degree of medical care to a backwater village. By the time the film opens, both have prioritized their senses of justice towards others–while starving their own sympathies. They tend to face their predicaments with good-humored hopelessness; the first night Meeta is a guest in Dr. Sunil’s home, she asks him if he ever got around to getting married–with an flattered note evident in her voice–and he cannot help but laugh sweetly. A particularly bittersweet vivisection of the feelings comes when Meeta entrusts Babu to Dr. Sunil for a consultation at the big-city teaching hospital; old colleagues naturally assume that (as both Meeta and Sunil might have preferred) the afflicted child is his own. But these passages, which in another film might be unmitigated melodrama, trend inexorably towards a reclamation of selfness, agency, and joy. So much abnegation, and then–!

To me, the most interesting performances of this film were those of Ashok Kumar and Ramesh Deo, who make for an unusual but believable father-and-son pair with their contrasting politics and interpersonal ethics. Although Shiv Prasad is a self-evidently despicable bully, Ramesh Deo plays him with the kind of supreme confidence that works its way around to being charisma. You can understand why people would want to follow him. Playing up the performative aspects of the union board campaign, Shiv Prasad even gets a proper song picturized on him (“Kon Sacha Hai Kon Jhutha Hai”); I’m not sure if I would vote for his dad on the basis of that performance alone, although I might be prevailed upon to buy a used car from him, or something. Ramprasad’s insistence on remaining in the general ward, in spite of the risk of infectious disease and numerous offers of a private room, keeps whole hospital hostage to his own garrulous, self-absorbed, weirdly charming bombast. Ashok plays Ramprasad as a deeply principled man whose principles the viewer is unlikely to condone; he is constitutionally incapable of remembering the name of anyone he deems unimportant. Despite lesser run-time, other long-term patients in the general ward also emerge as distinct personalities and a microcosm of the surrounding village: Dayaram (Anwar Hussain), Ismail (Iftekhar), Ratan (Jalal Agha), and Heera (Deb Mukherjee). Though the ward often seems on the brink of outright war, the sweet background romance between Heera and milkmaid Shyama (a very young Farida Jalal) treats us to a glimpse of a possible kinder future.

I was surprised to learn that S. D. Burman’s score for this movie netted him a National Film Award–not because it is in any way bad, but because it isn’t showy or hummable. Most of the songs serve to set tone rather than being a focal point of themselves; they underpin action like “Piya Tune Kya Kiya Re” or oversee the transitions between present moment and flashback as the title song “Zindagi Ae Zindagi” repeatedly does. (Both of those are sung by S. D. Burman, too.) There are, however, two songs that would fit for enjoyable listening in isolation. Heera and Shyama address the lovely “Khus Raho Sathiyo Khus Raho Sathiyo” to the whole ward as they prepare to leave Ashanagar. Although it truly is as happy as that mukhda would suggest, something can be made of the fact that we are told to rejoice only at these friends’ departure, that their best chance for happiness is in some utterly different place. Meena and Dr. Sunil trail behind the young couple step by step until they are over the hilltop and fully out of sight, as though trying to walk them to the doorstep of a second life. The most tuneful song of all also most directly expresses the film’s theme: “Teri Jat Kya Hai, Meri Jat Kya Hai.” The lyrics are warmly clever and the playful percussive accompaniment ably complements the picturization, in which a young Sunil tries to cheer his mother up by divining good humor out of an unjust situation.

I suppose the mostly abstract music suits the tone of this film, in which we spend so much time tuned to the fleeting, quotidian conversations of the hospital inmates and are sometimes asked to enjoy pure image–as in the long, lovely sequences spent following Meeta and Babu’s cross-country path toward Ashanagar. Those beautiful, attentively observed visuals highlight both a worthwhile world and the harm its precious human creatures so needlessly do to one another. One patient’s tattoo reads “Love is true, God is good,” but an more accurate motto for Zindagi Zindagi might be “Hope is real:” an infected joint, properly excised, can still bear weight. Even in Ashanagar, about half of the tubercular patients live. It could even be worth getting married about.