John Green, author of bestselling books including The Fault In Our Stars, is a passionate campaigner for eradicating tuberculosis. In his new book, Everything is Tuberculosis, he writes about the history of the disease, the role of the U.S., and why he decided to do something about it. An edited excerpt from an interview:

John Green in Washington, DC.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

A young tuberculosis patient receives medicines from a nurse at a TB hospital in Guwahati.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Your book is part poetic, part philosophical, capturing the story of a disease panning three centuries. What motivated you to write it?

About 1.25 million people died from TB in 2023. It’s overwhelming, and we don’t know how to process these kinds of numbers. I wanted to write about one person and his personal experience with tuberculosis as a way of humanising the disease. I met Henry at a tuberculosis hospital in Sierra Leone in 2019 and he looked pretty healthy, but his TB wasn’t responding well enough to antibiotics. I was in Sierra Leone to learn about maternal health, but when I came home from that trip, I learned that TB is still our deadliest infectious disease.

Patients undergoing treatment for tuberculosis at the Government Hospital of Thoracic Medicine at Tambaram Sanatorium, Chennai.

| Photo Credit:

G. Krishnaswamy

One in four TB patients who dies belongs to India. You are a strong advocate for availability of drugs. For drug-resistant TB, bedaquiline is now open to be manufactured by generic companies. How do we ensure access on the ground?

The TB response in India has gotten much better over the last 10 years due to people like Shreya Tripathi who sued her government in order to get access to the newest and best antibiotic, bedaquiline. Unfortunately, by the time Shreya won the court case and got access to bedaquiline, it was too late for her. I also tell the story of the young survivors of TB who worked with the Indian court system to establish that the bedaquiline patent should not be extended forever. India is the pharmacy of the world and that decision has made it possible for Indian manufacturers to develop bedaquiline that cost 60% less. Hopefully, that will mean fewer deaths from tuberculosis, but unfortunately, with the U.S. stepping back so much, funding to fight tuberculosis is in a real crisis now and it’s not clear who is going to step up. Countries like India have to step up into the vacuum that the U.S. has created. Many people who need bedaquiline still aren’t getting it due to complexities of distributing the medicine, especially to rural communities, and updating treatment guidelines.

A tuberculosis patient receives medicines at a clinic in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Actions of the U.S. government are being felt in developing countries, including India. How do you see such decisions impacting the goal of eliminating TB?

We know that diabetes, for instance, is a huge risk factor for TB, so is HIV. Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death from AIDS and so all of this is interconnected. TB anywhere is a threat to people everywhere there is. That’s why it’s devastating to see the U.S. government walk back on its long-term commitments to health funding. Look at the progress India has made in the last 30 years on child mortality. That’s one of the greatest successes in human history and to see us taking steps backwards is absolutely devastating.

A nurse prepares to give an injection to a tuberculosis patient at the Lal Bahadur Shastri Government Hospital, in Varanasi.

| Photo Credit:

AP

You have been advocating for eradicating TB before U.S. Congress.

The U.S. should care about TB for the same reason that all rich countries should care about it, which is that we became rich largely through extractive colonialism. That has resulted in a wildly unjust and unfair global social order, where some people have access to the newest medications and treatments and other people don’t. That’s a failure of a human-built system. We should also care about tuberculosis because there are 10,000 cases of tuberculosis every year in the U.S. We have a TB outbreak right now in Kansas. This is a prime example of what happens when we don’t do a good job of distributing global resources we have to address healthcare crises. I see this as a product of history. I see the current global TB crisis as a product of the long history of distributing resources unfairly and acting as if some lives matter more than others.

Have you won the cost battle yet with your advocacy? There is major struggle in sourcing a drug of importance, delamanid, that Japan-based Otsuka pharma manufactures, due to high costs ($800-$2400 for 6 to 18 months).

We’ve won the cost battle with bedaquiline but not the distribution battle. We have not won the cost battle with delamanid and that is essential to the future of fighting tuberculosis, because for fighting drug-resistant tuberculosis, delamanid is a very important drug. In countries like India, we need far more delamanid available so that we don’t have stock outs of that critically important drug, and cost is a major barrier there.

You write that in the 19th century being inflicted with TB (known as consumption back then) was fashionable.

In the early 19th century, it was widely believed that only white people could get TB. It was seen as a very ennobling disease that made you beautiful, gave you very pale skin, red cheeks from the fever and wide eyes. All of these became beauty standards in Europe and the U.S. And it was also seen as making you super intelligent, sensitive and a wonderful poet. Charles Dickens called consumption the disease that wealth never warded off, a disease that anyone could get, no matter how rich you were. In fact, the richest person in the 19th century, Jay Gould, died of tuberculosis in his forties. It was imagined as a very different disease from the way it is imagined now, as a disease of poverty.

In the book you write about your struggle with a highly resistant strain of infection which you treated with antibiotics.

It’s important that we invest a lot right now in finding TB cases and in treatment because of the risk of antimicrobial resistance. We are seeing TB that is resistant to more and more bacteria and we need to develop new tools and new classes of antibiotics as also do a good job of distributing current tools and making sure that people are getting timely treatment. My own experience with microbial resistance was a cellulitis infection behind my left eye, between the tissue of my brain and eye that became inflamed. My eye hurt, I went to the doctor. And everybody panicked because it’s pretty close to your brain. The infection wasn’t responding to the first or second line of antibiotics, and so I was hospitalised for a week. It was a really scary experience and it gave me a lot of time to sit, think, look at the ceiling and wonder if I was going to die as a result of this infection. But it was also a reminder that antimicrobial resistance is a threat to all of us.

An article in ‘NYT’ describes you as somebody who wants to eliminate TB, which is an entirely curable disease. As a young adult writer of influence, perhaps you’re on the right track. But you mention in the book that it is very tough to entirely eliminate TB. India has set an ambitious goal to eliminate TB by 2025. Do you think it’s hard to do that?

It would require a lot of resources to eliminate tuberculosis worldwide. But it’s a great investment because every time we end a chain of transmission, we never have to worry about it, because this is a curable disease. In the U.S., hundred years ago, we had almost as many hospital beds for TB patients as we had for all other health care conditions combined. And now we spend very little money on TB because we’ve mostly eliminated it. I believe that will be the case in India, in Sierra Leone, in South Africa. Or in the Philippines or Indonesia. But it won’t be the case until we engage in active case finding, which means sending an army of people out to find TB. Not waiting until people are so sick that they come into a clinic or hospital. It means getting treatment to every single one of those people and it means offering preventive care to their close contacts, their family members. If we did that, we could eliminate tuberculosis. It would require a big investment, but we know that it would pay off in a big way because we know that for every dollar we invest in tuberculosis research and response, we get $40 of economic benefit in return.

Can you elaborate on your advocacy with diagnostic company Danaher to reduce TB test prices?

Danaher manufactures a molecular test called GeneXpert, which can tell whether someone has TB within two hours, whether they’re resistant to one of the first line drugs, and which antibiotics is this person most likely to respond to. Unfortunately, the tests are expensive, and out of reach for low-income countries. We are still diagnosing a lot of tuberculosis through the way we used to in 1880s (by the method of X-rays and sputum microscopy.) I was a part of pressuring Danaher to lower the price of its standard TB test cartridge to produce it at cost instead of making a profit from it, since they make plenty of profit from other tests and in charging rich countries for tests. Eventually, Danaher agreed to cut the price of their test but there’s still a long way to go. But that progress is real and worth celebrating. The cost of test cartridge was $10 and now it’s $7.97.

What is your parting shot to readers when it comes to tackling TB because this is clearly going to be a long fight?

The first battle will be to get USAID and as much funding as possible back in play so that we can have at least some response to TB coming from the U.S. government. I’m also looking at prices for diagnostics and the drugs that are still too expensive, like delamanid.

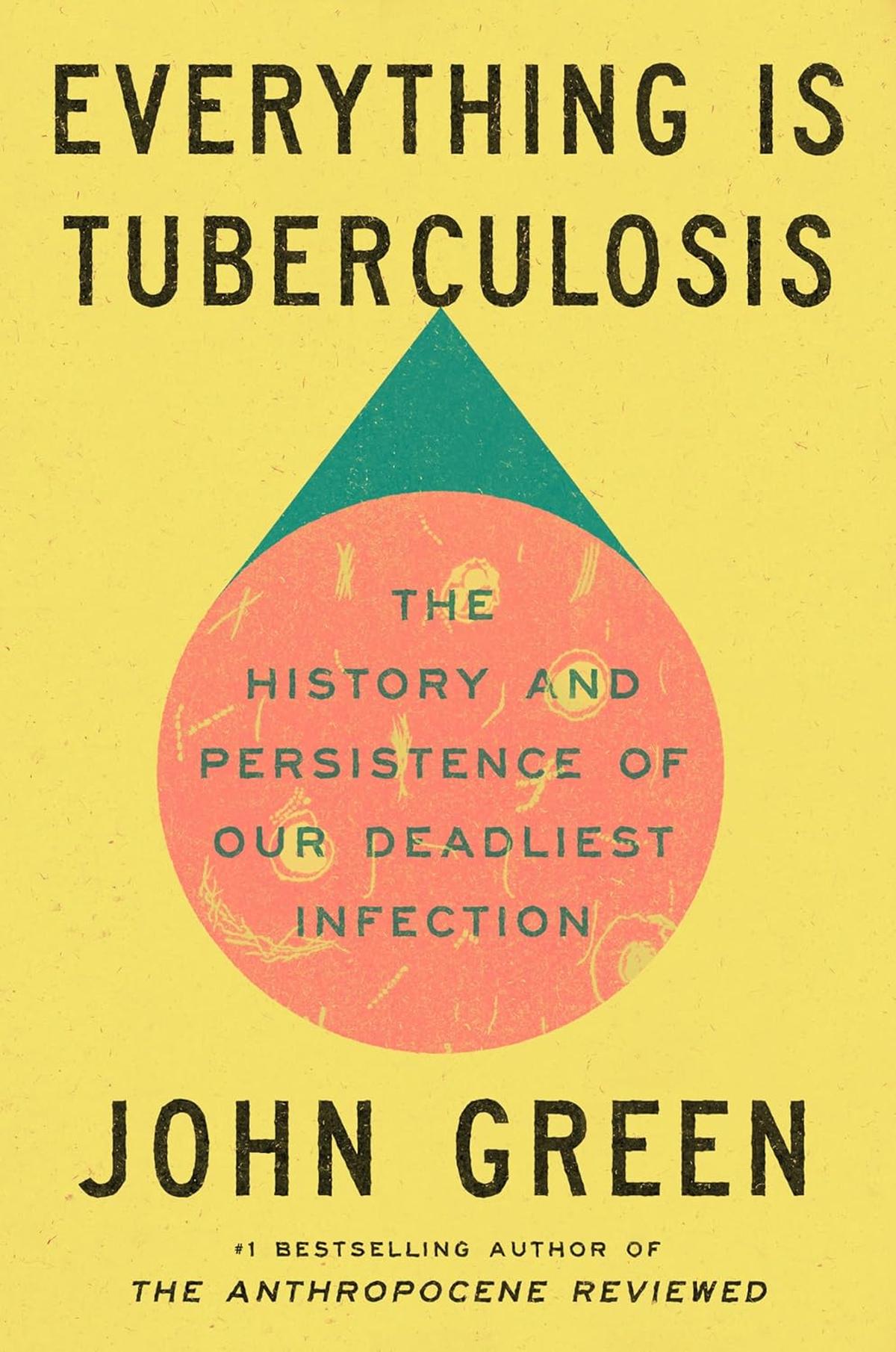

Everything is Tuberculosis; John Green, Penguin Random House, ₹999.

Published – April 04, 2025 09:01 am IST