When Nayak (1966) won a special award at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival, the great Italian poet-filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini was on the jury and was known to have shown great enthusiasm for the film. Sixty years later, the crisis of conscience depicted in the film, newly restored, forces one to reimagine its contours. Ray’s cinema evokes new sensations with each viewing, the intricacies in his films taking on new life for the introspective audience. Years ago, Marie Seton, in her magnum opus, Portrait of a director: Satyajit Ray (1971), had alluded to the presence of allegory in Nayak. A European critic, in reviewing the film, had found its content to be more substantial than the Greta Garbo-John Barrymore classic, Grand Hotel (1932), more lucid than the Italian auteur Fellini’s 8½ (1963), and more alluring than Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957), and far more entertaining than all three.

Also Read | Satyajit Ray wrote 52 letters to ‘Jana’ over 16 years. Who was she?

Such exaltation was not uncommon when it came to Satyajit Ray. One would often come across reverent remarks declaring him to be “among the most intuitively right in all movie-making”, “one of the most conscious artists who ever lived”, “our greatest living director”, etc. Western critics have compared Ray to the likes of Chekov, Renoir, Buñuel, Antonioni, Éric Rohmer, Howard Hawks, etc., and one of the greatest proponents of realism in cinema. Andre Bazin expressed admiration for the Indian director after watching Aparajito. But American film critic Pauline Kael alone came closest to capturing the essence of his cinema: “Ray’s simplicity is arrived at, achieved, a master’s distillation from his experience”.

Let us start our journey with the elements that leap to the mind at the first instance.

Train

The metaphor of the train in Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1955-59) has been the subject of unyielding discourse in world cinema for critics and film academics alike. His 1966 film, Nayak, digs into a complex narrative, conceived and realised within the confines of the train, in itself a phallic symbol.

In Pather Panchali (1955), the train chugs and whistles its way through the darkness in its first appearance off-screen as Apu sits studying on the porch, next to Harihar. A few feet away sits Sarbojaya, braiding Durga’s hair, and Indir, engrossed in futile attempts at threading a needle. The whisper of modernity–remote and unattainable–brushes past the quiet banality of everyday rural life. When Apu and Durga see the train for the first time, the rustic imagery of agrarian farmlands around them disappears for a moment as the train hurtles ahead. And in Apur Sansar (1959), the final film in the trilogy, Apu’s tiny rooftop universe is located beside the railway track, transformed into a complex metaphor as a gloomy, burgeoning modernity unfurls itself in all its contradictions in a haze of billowing smoke and clatter. After Aparna’s death, as time stands still, Apu decides to free himself from the chokehold of misery, presumably by throwing himself onto the railway track. The train motif thus turns into a paradox of civilisation.

And in Nayak? In his 13th directorial venture, Ray turns to a unique storytelling as the entire narrative unfolds within the train. Leo Braudy had mentioned Ray alongside Renoir and Rossellini in his work, The World in a Frame (1976), to illustrate his concept of “open cinema”, where the plot becomes as extension of the real, natural world; yet, in Nayak, Ray subscribes to Braudy’s presumption of a “closed cinema” as he conjures up within the air-conditioned glass panels of the train (the drapes cannot be drawn despite one’s best efforts) a cosmos that affords one only passing glimpses of the world outside. Nayak unravels aboard that which, for Apu, stands for an obscure hallmark of civilisation, piecing together bit by bit the dreams, ambitions, tensions, anxieties, greed, fears and insecurities of a disquieting modernity.

From train tracks to psychological traps, Satyajit Ray’s Nayak is a haunting meditation on moral failure, cinematic realism, and post-Independence disillusionment.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

The train in Nayak denotes not only the fast-paced contemporary life, but also its beauty–a specimen of what Aldus Huxley called “organised lovelessness”. A symbol of the rhythm of life. In Ray’s own words, his films offer no sentimental resolution, etching out, instead, the inherent schism between the real and the superficial, the “eye” as opposed to the eye, the past vs the present, cinema vs theatre, games vs play, and the paradoxes of the irrational vs stark rationalism, carved in discreetly dripping, invisible blood.

But above all, the train is a symbol of the phallic. The unspoken story of Arindam (Uttam Kumar) and Pramila (Sumita Sanyal), unexplored, the hint of it teasing the viewer as it uncoils in the deep underbelly of the film. In an early scene, Arindam answers the telephone.

Arindam: Yes?

A woman’s voice: You’re going to Delhi?

Arindam: Yes

The woman: By train?

Arindam: By train

The woman: Would you like me to meet you at the station?

Arindam: I’d rather you didn’t

We see Pramila and Arindam at the onset of their relationship, its fallout suggested only in the second dream sequence, reminiscent of an expressionist work of art. We are briefly introduced to the stage director Sankarda (Somen Bose), who played a pivotal role in Arindam’s life. Even the latter’s association with the trade union leader, Biresh (Premangshu Bose), reveals itself within the space of two concise sequences. Pramila’s tale alone remains unfinished. Ray chooses to give the audience the merest of hints, like fractured images on broken glass. It seems obvious that Arindam dropped all pretence of modesty after that first meeting and let himself be seduced, but we never quite see the affair unfold.

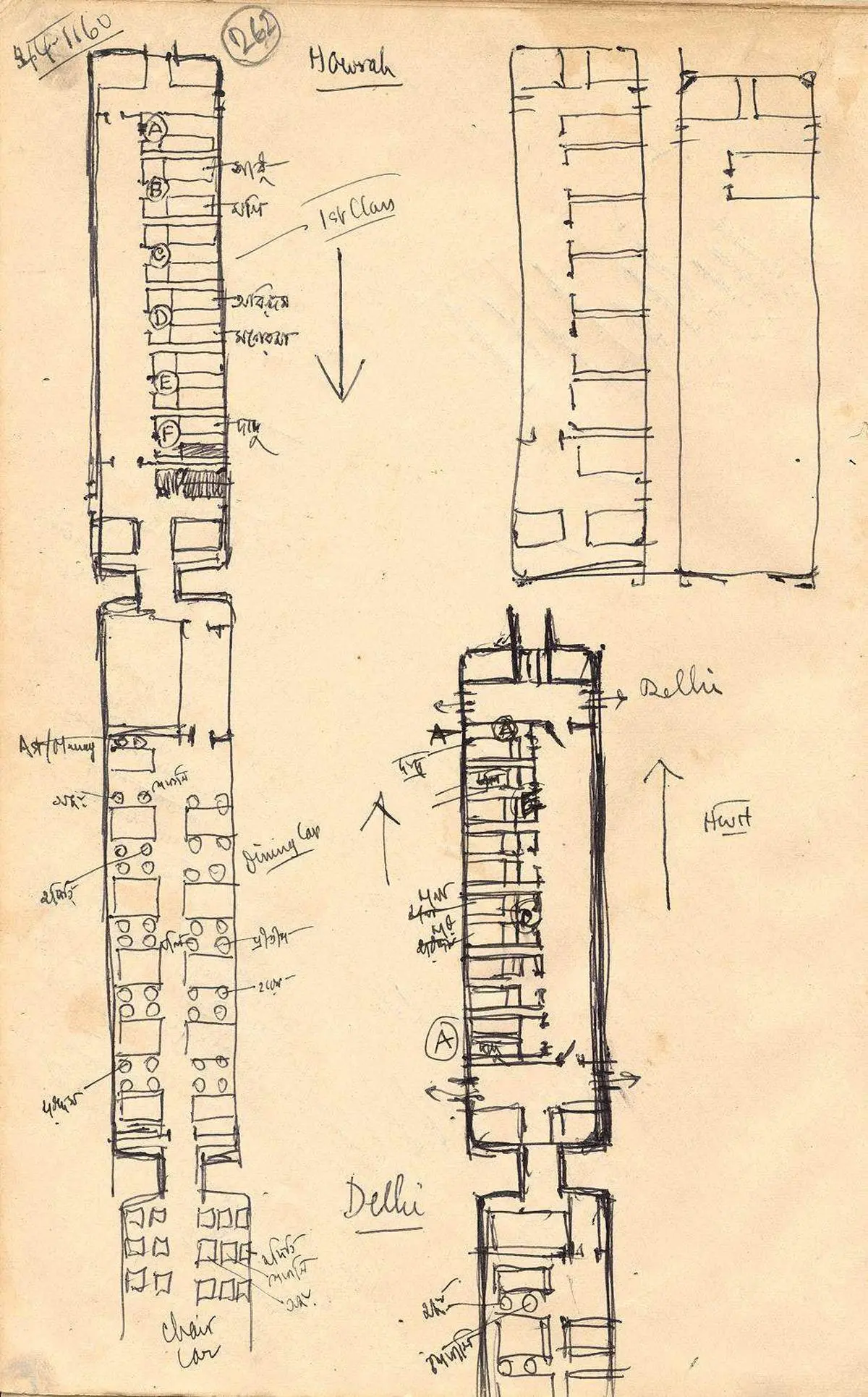

Satyajit Ray’s sketchings from his personal notebook.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

An inescapable dream sequence. Crowds of men and women in dark glasses behind a white door. Pratidwandi (1970), perhaps, is the only other film where such poignant expressionism spills onto the screen. It is clear from Arindam’s conversation with Aditi after the first dream sequence that both dreams rise from the depths of his consciousness. The second is an expression of his guilt-stricken conscience, the loneliness of a solitary existence bleeding into each frame with erotic undertones.

The scent of temptation finds its way into the roving eyes of industrialist Haren Bose (Ranjit Sen), whose family shares a coupe with Arindam. He lusts after Pritish Sarkar’s (Kamu Mukherjee) (who runs an advertisement firm) wife with every bone in his body “You have a charming wife. Molly Jolly Folly–by Golly! You are lucky, Mr. Barman”. In his drunken state, he makes a gaffe addressing Sarkar as Barman. Pritish convinces Molly to put on an act of sensuality. “This is just a game, Molly”. Molly (Sushmita Mukherjee) refuses to comply. Yet, she doesn’t dither when appealing to Arindam to help her make inroads in the film industry. The spirit of Pramila speaks through Molly. Do her eyes tantalise? Molly is ready to shed her inhibitions, refusing to “prostitute” herself for one cause, only to do so for another.

Henri Micciolo believes that Molly’s physicality (as she gives up one act for another) stands at the end of the continuum at the other end of which lies Arindam’s moral prostitution. Even his honest leftist friend Biresh doesn’t hesitate to “use” his image; all he has to do is present himself before the workers… just once. Arindam refuses; he knows that Biresh judges him for his decision. He lacks the courage to shatter the glass ceiling, but neither does he enjoy humiliation.

Prison

The prison motif at the very beginning of the film is crucial. The black and white credit title reminds one of the bars of a prison as the back of Arindam’s head slowly fills the frame. He is brushing his hair. With the last stroke of his brush he is keeping up appearances, while at the same time behind the prison bars stands a man, caged.

Shortly after, the camera pans to reveal his double-bedded room (Arindam is a bachelor), the walls mounted with photographs of the star. He exists in the world of mystique, as he himself explains to Aditi (Sharmila Tagore) later on. An almost narcissistic preoccupation with himself.

His manager, Jyothi (Bimal Ghosh), asks him. “Tell me, what does the film have to offer? Apart from you.”

Arindam: I’m there. Isn’t that enough?

There is, too, a peculiar contempt for the audience. An urge to run them down with a steam roller.

In the first dream sequence, Arindam cries out to Sankarda for help as he drowns in a quicksand of money; this is a trap within a trap, there is no way out.

Later, Aditi compares a star’s life with a plant ensconced in glass. When, after the second dream, the exhausted, inebriated star finds himself in front of the open train door, according to certain Western critics, with an intent to end his life, the serpentine railway tracks seem to shackle him from all sides. The camera’s eye stares at the iron bars, akin to a great slumbering reptile.

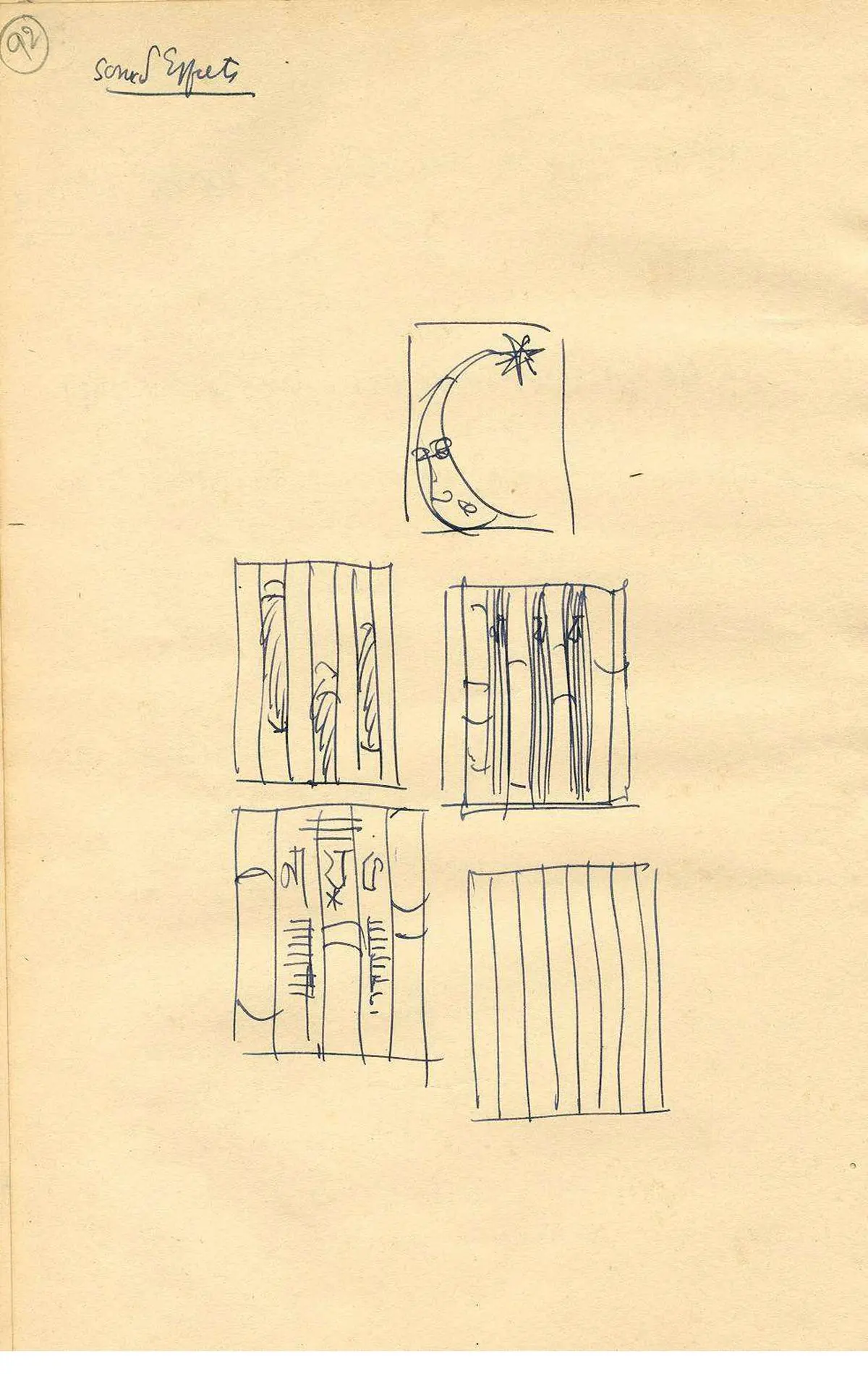

Satyajit Ray’s sketchings from his personal notebook.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

A powerful metaphor for an iron cage. It is the young journalist, Aditi, who drags him out of his perilous prison quite by chance. Aditi watches him sans spectacles as his insides break into pieces–a bare-eyed witness to an agonising truth. Pangs of conscience and remorse course through him. At the summit of success, a nameless anguish shakes Arindam to the core. “As if a gaping void… it’s stuck right here. Not a soul I can share it with…” A gut-wrenching emptiness that is a recurrent theme in several of Ray’s characters. Narsingh, Ashim, Siddhartha, Shyamalendu, Somnath. Only the backdrop varies. A call for help, begging to be saved, to wriggle out of the endless supply-demand chain beneath the boundless skies.

Money

Money plays a vital role in Nayak bringing to the fore the contemporary socio-economic tendencies of 1960s India. Political independence, hard-earned, is already a thing of the past. And an almost unholy fascination for wealth and riches has gripped certain social classes. Only a few stand out: Aditi and a middle-class couple who are her fellow travellers. As he tries to woo industrialist Haren Bose, Pritish, the advertising agent with the twisted mind, observes, “But you know, most youngsters these days tend to lean a little left.”

As Uttam Kumar’s Arindam unravels aboard a moving train, Nayak transforms into Ray’s critique of fame, capitalism, and the actor as a prisoner of image.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

The cash that Arindam counts out before the start of his journey could very well be dirty money. Does he perhaps fear losing himself, and is it this angst, buried deep in his subconscious, that gushes out in his dream as he finds himself sinking in piles of money (note the skeletal claws jutting out of the heaps)? This is not just a fear of being toppled from stardom but a deep-rooted fear of survival in a world steeped in materialism. He is ecstatic, wandering around in slow motion as money showers down on him; his face glows in rapturous joy–perhaps implying an increasing affinity towards material wealth.

Perhaps he is losing touch with his creative self, which in turn has hindered him from doing justice to his last film! Does this mean that somewhere down the line, it is Sankarda who ends up having the last word? Why else would he appear in a grotesque costume and make up to rescue Arindam from drowning?

From industrialist Haren Bose, to Pritish Sarkar, and even the robed monk who shares a coupe with Sarkar and his wife, all are caught in an infinite loop of worldliness.

Pauline Kael notes that Ray’s films seem to document social realities. In Aranyer Din Ratri (1970), the economic class and stature of the four young protagonists determine their social conduct. Hari nearly boasts to Duli, “He gave you five rupees, is it? I’ll give you 25!” Ashim, whose city-bred arrogance defines him from the very start, is seen throwing his weight around; he is by far the most financially secure of the lot. Ray is forever seeking to carve out a deep, inherent construct underneath the glossy exterior. The parallels between Arindam’s life and that of actor Uttam Kumar, who essays the role are striking. Both started out on the stage, got catapulted to stardom, and both got involved with another woman. Both are on the lookout for triumphant success–they want to go ‘to the top, the top, the top.”

Film actors end up as little better than puppets in the hands of the director, the cameraman, etc. It was the legendary stage actor-director and playwright, Sisir Bhaduri, who had originally had this exchange with Ray, says Ray expert Andrew Robinson. The evolution of acting is an important element within the film. Before Pather Panchali, film actors would indulge in an over-dramatised, larger-than-life acting that started changing post 1955 with the release of Ray’s first film. Like Arindam, Uttam Kumar ushered in an era of natural, restrained acting that worked better in front of the camera. Thus, the entire tragic arc of Mukunda Lahiri (Bireswar Sen), who plays the yesteryear actor now fallen from grace, is built on a historical premise. After Uttam’s success, the era of overacting in films gradually faded into oblivion. As Ray himself stated multiple times, cinema calls for a more muted approach when compared to theatre.

Echoing the anxieties of a newly independent nation, Nayak—a masterclass in closed cinema—remains one of Ray’s most layered and intimate films.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

The musical–often Mozartian–structure is recurrent in Ray’s cinema, but the master filmmaker also engaged in a deeper socio-structural analysis. For instance, in Nayak, it is the dialogue between two individuals that forms the crux of the plot. After her first two films with Ray, Sharmila Tagore finds herself enacting roles that interrogate the inner turmoils of man against a gradually rupturing social fabric. Arindam himself teases her, “You’ll be perfect in the role of conscience.” In Aranyer Din Ratri and Seemabaddha (1971), Tagore returns in similar roles, written along the same vein–quizzical, and introspective–shining a lone candle of morality in a slowly crumbling society.

In Ray’s words, Aditi is “slightly snooty, sophisticated”. He gave Tagore a pair of heavy glasses to give her a more mature look. Aditi stays unfazed by Arindam’s glamour until she discovers the extent of his helplessness beneath the facade. She takes a conscious decision to steer away from her inquisitive, journalistic approach, refusing to exploit Arindam at his most vulnerable. She steps away, thinking it prudent to let it go.

In an interview with Aparna Sen in 1986, published in the popular women’s magazine, Sananda (Vol. 1), Ray noted, “I think I have perhaps a subconscious conviction about women–that they are basically more honest, more forthright–because physically they are the weaker sex, there are perhaps certain compensating factors in the general makeup of their characters.”

Also Read | ‘His eyes spoke everything’: Raghu Rai remembers Satyajit Ray

A young girl and a child are the only witnesses to the star’s inner turmoil. Bulbul, alias Sairindhri (Lali Chowdhury), is afflicted with persistent fever. She watches Arindam take a sleeping pill from the upper berth. Bulbul asks innocently, “Won’t you be able to sleep without the pill?” Later on, she is unable to hide her distress as he stumbles into the compartment, completely hammered.

The little girl, Rita, is the other witness. Toward the start of the film came that simple, innocent exchange.

“Kya naam hai tumhara?”

“Rita. Aur tumhara?”

“Mera naam Arindam Mukherjee.”

Later, the sight of the actor in the corridor, wasted and troubled, sends Rita scurrying.

Broken glass over a bathroom sink, a bottle of drink tossed into the darkness, serpentine railway tracks, undisclosed anxieties like molten lava, unrelenting silence, and conversations with Aditi, who sees through the chaos–Arindam cuts across it all. The next morning, the mask is back on. The star is in self-incarceration, sporting dark glasses with an empty smile plastered mechanically across his face.

Chinmoy Guha is an essayist, translator, and scholar of French language and literature, currently serving as Professor Emeritus at the University of Calcutta.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/cinema/satyajit-ray-nayak-film-analysis-berlin-award/article69521583.ece