On May 5, 2023, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), officially declared that the global COVID-19 pandemic was no longer an emergency.

Earlier that year, in January 2023, WHO still maintained that the COVID-19 pandemic remained a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), three years to the day after it sounded the highest level of global alert. In September 2022, Dr. Tedros said that the “end is in sight” for the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the world was on its guard again at the beginning of 2023, with new waves breaking out in China after it lifted restrictions in December 2022.

Also Read: The pandemic — looking back, looking forward

Vaccination had widely been considered the mode to bring an end to the pandemic, and the COVID-19 era witnessed a global mobilisation effort. The UNICEF COVID-19 market dashboard noted that 17.2 billion doses had been secured globally. Of these, 13.64 billion had been administered across the world, according to the WHO-UNICEF COVID-19 Vaccination information hub.

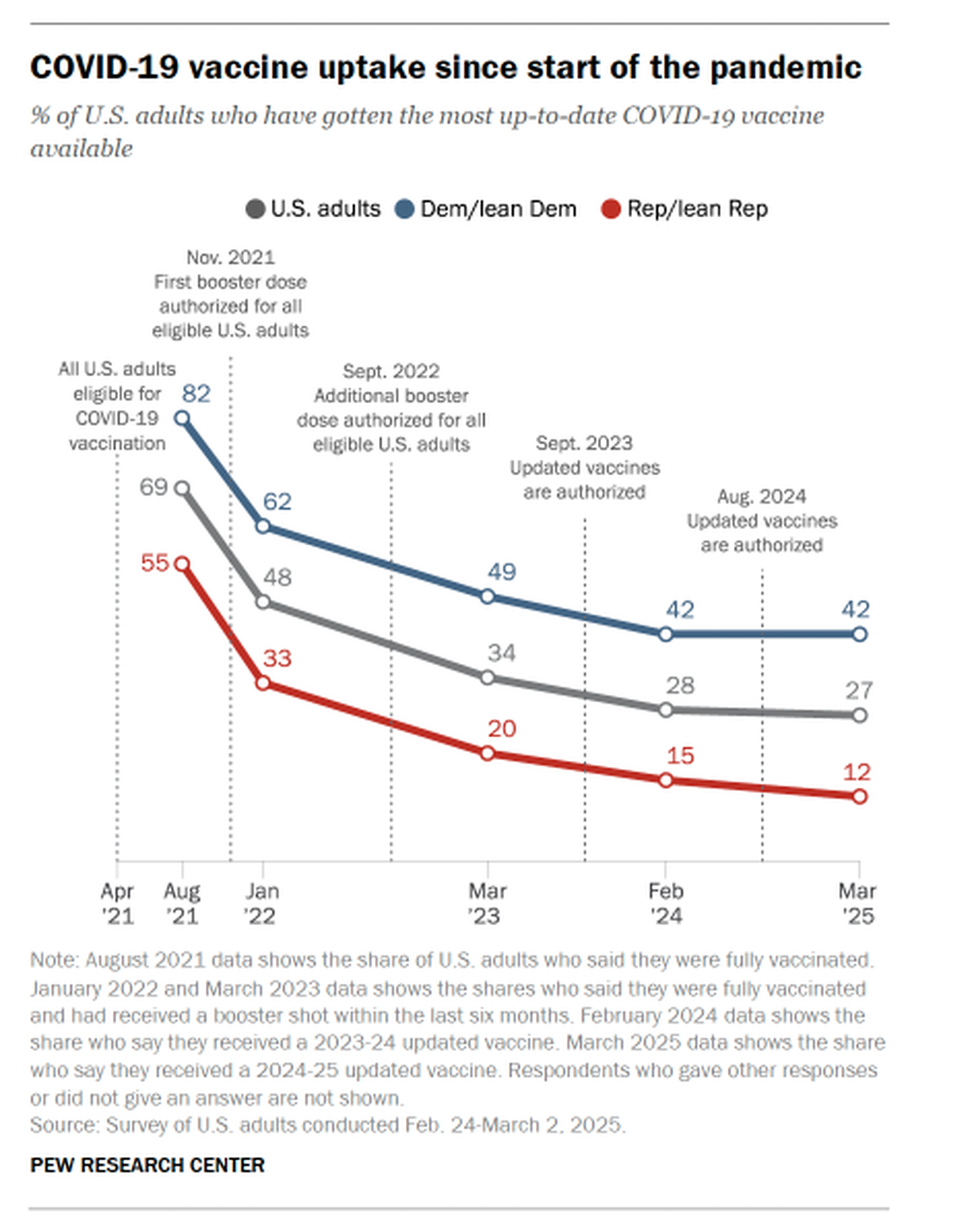

The fear about COVID-19 has, by and large subsided, although it remains extant in pockets across the world. The global vaccination drive, however, is at an end. A recent study by the Pew Research Center found that more adults in America reported getting the updated flu shot than the updated COVID-19 shot after both vaccines became available in August last year.

Here is a throwback to the historic effort to vaccinate the world’s public, amid loss, fear, skepticism and anti-vaccination sentiment.

The vaccination rate

As of March 13, 2023, the global rate for vaccination stood at 72.3% vaccinated (at least one dose) and 67% fully vaccinated, according to a coronavirus tracker run by TheNew York Times. This was the last update since many countries stopped regularly reporting vaccine data post this period.

Of this, four nations- Macau, Brunei, U.A.E and Qatar- reported vaccination rates above 99% – including those who were fully vaccinated. Per government data, Macau used inactivated virus vaccines from Sinopharm CNBG Beijing and mRNA vaccines from Fosun-BioNTech. Meanwhile, Brunei approved the emergency use of the Sinopharm (BBIBP-CorV), Oxford-AstraZeneca, Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines. Per the Emirates Health Services, U.A.E residents had access to Pfizer-BioNTech, Sinopharm, Moderna, and Hayat Vax, and the GEN2-Recombinant COVID-19 Vaccine (CHO Cell) for booster doses. Qatar offered the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines.

India still updates its COVID-19 dashboard, managed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, noting active cases, discharged patients and total deaths. The vaccination tracker however has not been updated since June 19, 2024, where the total vaccination was reportedly 220,68,94,861 — above 2.2 billion doses. At this point, India reported a vaccination rate of 75%, with 70% fully vaccinated. Several persons also took boster doses.

Mainland China, the origin point for the pandemic, reported a total of 94% first-dose coverage- with 91% fully vaccinated. In December 2022, China lifted zero-COVID restrictions after almost three years, followed immediately by a major spike in COVID-19 infections and deaths.

China’s vaccination programme largely relied on indigenously developed vaccines- CoronaVac, manufactured by Sinovac, and Sinopharm, which are both inactivated whole- virus vaccines. Researchers, however, say that mRNA vaccines manufactured by Pfizer and Moderna are more effective. A paper published in December analysed data from Singapore and found that mRNA vaccines were more effective than Chinese vaccines in preventing severe illness in those over 60. China, however, refused offers of surplus mRNA vaccines from the EU.

While there were still countries struggling to achieve widespread vaccination in 2023, the greatest number of vaccines had already been given out in 2021. By June 2022, world COVID-19 vaccinations had touched 12 billion, which increased gradually to 12.9 billion by November 2022. The vaccination programme slowed down considerably in 2022, because most people worldwide had either received two vaccine doses or developed better resistance due to exposure to the virus.

As of March 2023, there were still a few countries which struggled with a low vaccination rate. At the bottom of the ladder were Burundi (0.3%), Yemen (2.6%), Haiti (2.1%), Papua New Guinea (4.2%), Madagascar (8.6%), Democratic Republic of Congo (13%), Congo (13%), Gabon (14%), Cameroon (15%), Senegal (16%) Mali (18%), Algeria (18%) and Syria (19%). It is unclear whether vaccination rates went up after the official end of the pandemic. Further, some countries were absent from the NYT tracker, since they do not report vaccination data.

Causes for poor vaccination rates included both lack of access to vaccines and vaccine hesitancy, among other factors. Vaccine hesitancy is an issue even in developed countries, with approximately 30% of Americans never choosing to get fully vaccinated. A World Bank working paper estimated that one in five adults in 53 low and middle-income countries had been hesitant to receive a vaccine between late 2020 and the first half of 2021.

The vaccines

The following are some vaccines used to stem the spread of the COVID-19 pademic, along with the manufacturer (data from WHO’s COVID-19 vaccination dashboard):

Oxford Astra Zeneca- Vaxzevria

Beijing CNBG- BBIBP-CorV

Bharat Covaxin

CanSino- Convidecia

Chumakov- Covi-Vac

Finlay- Soberana Plus

Finlay- Soberana-02

Gamaleya- Gam-Covid-Vac

Gamaleya- Sputnik-Light

Janssen- Ad26.COV2-S

Julphar- Hayat-Vax

Moderna- Spikevax

Pfizer BioNTech- Comirnaty

Serum Institute of India- Covishield

Sinovac- CoronaVac

Covishield, Covaxin, Sputnik V, CorBEvax, Covovax were the main vaccines in use in India. Others, such as ZyCov-D received the nod for emergency use. Bharat Biotech also launched a nasal COVID-19 vaccine— iNCOVACC.

Other vaccine candidates were developed and tested later, with oral, intra-nasal, aerosol and inhaled vaccines. A total of 64 vaccines were approved for use by at least one national regulatory authority.

Of this, 12 were a part of the WHO’s Emergency use listing (EUL): AstraZeneca Vaxzevria, BBIL- Covaxin, CanSino Convedicia, Janssen Ad26.COV 2.S, Moderna Spikevax, Novavax- Nuvaxovid, Pfizer BioNTech Comirnaty, Pfizer BioNTech Comirnaty (bivalent), SII Covishield, SII Covavax, Sinopharm Beijing -BBIBP- CorV, and SinoVac- CoronaVac, SK Bio- SKYCovione.

The EUL process seeks to establish if new health products are suitable for use during public health emergencies. The first vaccine which received emergency use validation during the pandemic was the Comirnaty COVID-19 mRNA vaccine manufactured by Pfizer/BioNTech. The Comirnaty vaccine required storage using an ultra-cold chain, needing to be stored at -60°C to -90°C degrees. Several other vaccines too needed to be stored at a precise, cooler temperatures, posing dual challenges for storage and distribution, particularly in hot countries.

Not every vaccine has been equally effective against COVID-19. For example, data indicates that monovalent Omicron XBB vaccines provide slightly better protection as contrasted with those containing bivalent variants or monovalent index viruses.

The global vaccination drive

A total of 13.64 billion COVID vaccine doses were administered globally. As per data from the WHO, as of December 31, 2023, 67% of the world population had been vaccinated with a complete primary series (in most cases two shots) of a COVID-19 vaccine, while 32% had been vaccinated with at least one booster dose.

Also Read: Long-term study finds COVID-19 increases diabetes risk

While WHO and UNICEF maintained a COVID-19 vaccination information hub during the pandemic years, annual COVID-19 vaccination data will now be collected through the WHO-UNICEF Joint Reporting Form on Immunisation. Final figures for 2024 will be collected from March to June 2025 and released in July 2025 with other immunisation data.

A detailed visualisation about the global efforts to vaccinate people against COVID-19 was created by a collaborative effort between CEPI, GAVI, UNICEF and WHO, noting milestones in the production and distribution of the vaccine. The COVID-19 vaccine was unique in that its development and clinical trials had to be squeezed into a narrow timeframe, making it the fastest-developed vaccine in history. Just 326 days after the virus’s genomic sequence was published, WHO issued the first EUL authorisation for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Normally, new vaccines usually take an average of 10 years to develop.

By the end of April 2021, nearly every country had introduced the vaccine. Adequate supply was the next issue. High income countries had a headstart and signed contracts with pharmaceutical companies for more supply than needed. Vaccine hoarding and control over the supply chain hindered access to vaccinations for lower-income countries.

Establishment of cold storage chains for storage and transport of the heat-sensitive vaccines was important, too. Further, manufacturing infrastructure was also vulnerable to the impact of the virus. An example was what happened in March 2021 in India. At this point, India was the home of the largest vaccine manufacturing industry in the world. In February and March 2021, it seemed like India would escape the worst of the pandemic: althought it saw high caseloads, it also saw record recovery rates and a lower number of deaths contrasted with its enormous population. However, the arrival of the Delta variant upended the nation. There were around 60,000 new cases a day and a crushing load on the country’s health infrastructure, which faced a shortage of hospital beds, oxygen cylinders and medicines. This was a stiff hike from 15,000 cases a day barely weeks ago. In the face of this new, deadly wave, India suspended vaccine exports to other nations, even with signed purchase orders. Supply was redirected to domestic shores, to try to quell the rising caseload.

An additional challenge was that the COVID-19 vaccines had to be delivered to all age groups, and not just children, as was the case with other immunisation programmes. The three groups which were sought to be prioritised were frontline workers, the immunocompromised and the elderly. Although some regions had adult vaccination programmes— for flu, for example— not every country had this set-up in place.

Ensuring global vaccine access was an uphill task for global health networks. GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, led a global effort to send vaccines to poor and middle-income countries, termed a “historic attempt to achieve global equity.” GAVI, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), WHO and UNICEF co-convened COVAX, the vaccines pillar of the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, which in turn was a global collaborative framework to end the pandemic. The COVAX Country Readiness and Delivery team (CRD) developed the COVID-19 Vaccine Introduction Readiness Assessment Tool (VIRAT), which sought to prepare countries for the quick licensing of vaccines, and also help them deal with policy measures, and logistics pertaining to the introduction and deployment of the COVID-19 vaccines.

The G7 group of advanced economies called for donation of at least one billion vaccines by high-income countries, to aid 92 low and middle income countries which were part of the GAVI Advance Market Commitment supported by the COVAX facility. 1.97- 1.99 billion doses were delivered to 146 countries through COVAX, with prices per dose ranging from $2 to $120. To help vaccinate the public, GAVI, UNICEF and WHO launched the COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Partnership (CoVDP) in January 2022, which supported the AMC 92 and focused on 34 countries which were at or below 10% vaccination coverage. COVAX and the UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) had also set up the COVAX Humanitarian Buffer to fill in the gaps in global vaccine access. (The Buffer stopped accepting new applications after December 31, 2022.)

Although GAVI’s programme was to be wound up towards the end of 2022, on December 8, 2022 its board approved the continuance of its COVID-19 vaccinations in countries supported by the GAVI COVAX -AMC. As per a press release, while priority was to “help countries raise coverage levels and boost high risk groups,” the Board also endorsed plans to start preparing for future evolutions of the virus. COVAX had in place plans for worst-case scenarios and explored “integrating future COVID-19 vaccinations into GAVI’s core programming…” also recognising the need to reduce “the additional burden a specialised emergency response places on countries.”

Post pandemic observations

Seemingly, the COVID-19 vaccine has not become a mainstay of the vaccine basket. In a study conducted in November 2024, 60% of Americans said they would not get an updated COVID-19 shot. Per another Pew Research Center study in March 2025, 53% of the surveyed Americans got neither the flu shot nor updated COVID-19 shot, contrasted with 22% who have gotten both. One-in-five got the flu shot but not the COVID shot, while 5% had gotten the COVID shot but not the flu shot. Democrats were far more likelier than Republicans to get either vaccine; further, Democrats were also more likely than Republicans to report getting the updated COVID-19 vaccine (42% vs. 12%). This is even as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended the updated vaccine to everyone aged 6 months and older before the fall and winter months to protect from severe disease and hospitalization.

Efforts are still underway to strengthen health networks for future pandemic preparedness. In April 2025, after nearly three-and-a-half years and 13 rounds of meetings, WHO member-states agreed on measures to prevent, prepare for and respond to pandemics. On April 16, the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body finalised a proposal for the WHO Pandemic Agreement. The draft, described as a “generational accord to make the world safer,” is to be adopted this month by the World Health Assembly.

The African Union, GAVI, and the G7 group of nations are engagaing in a 10-point action plan to enhance diversification of regional vaccine manufacturing. Meanwhile, CEPI is building a network of vaccine manufacturers in the countries of the Global South, building capacity to produce advanced vaccines to combat emerging public health crises within 100 days.

Some infrastructure gains made during the pandemic are sought to be retained. Africa CDC’s Pathogen Genomics Initiative used data from the pandemic to increase training in genetic sequencing and data analytics, and deliver equipment to researchers. Further, WHO and its partners launched an mRNA vaccine technology hub in Cape Town. Cold storage facilities and disease surveillance systems had been scaled up during the pandemic; these are now being put to use for other purposes.

So also, vaccination networks built during the devastating dates of the pandemic can now be used to address other public health concerns.

Published – May 04, 2025 11:44 am IST