Her day begins with a quiet prayer and a glance at the faded calendar, marked with yet another hospital appointment. For over two decades, Gowramma’s life has revolved around needles, blood bags, prescriptions, and silent strength.

Gowramma is the mother of two grown-up children — Tarun and Santosh — both living with thalassaemia, an inherited blood disorder characterised by reduced haemoglobin production.

Every few weeks, the children need blood, life-saving transfusions that keep them alive, but slowly poison their bodies with iron. The medicine to fight this iron overload is expensive, and the bills never stop. The family has a small garment shop at Peenya, an industrial area in the northern part of Bengaluru, and is struggling to meet an avalanche of medical expenses. Gowramma has not been able to get the free medicines from the government-run Victoria Hospital for the last four months.

At Sunkadakatte, a semi-urban locality in west Bengaluru, life is a daily struggle for 19-year-old Mubeena Ruqsar, who lives with her parents. She was diagnosed with beta-thalassaemia major at just six months. Since then, blood transfusions every three weeks, countless needles, and a growing pile of medical records have all been part of her routine.

Her father, Rahmathulla, works as a mechanic in a local garage. Her mother, Sakina Banu, once dreamed of becoming a teacher but now dedicates every waking hour to managing Ruqsar’s health — tracking her transfusion schedules and watching for signs of fatigue, fever, or distress. They live in a rented two-room house, and save every extra rupee for hospital visits and medicine. The young adult’s treatment involves not just transfusions but also expensive iron chelation therapy.

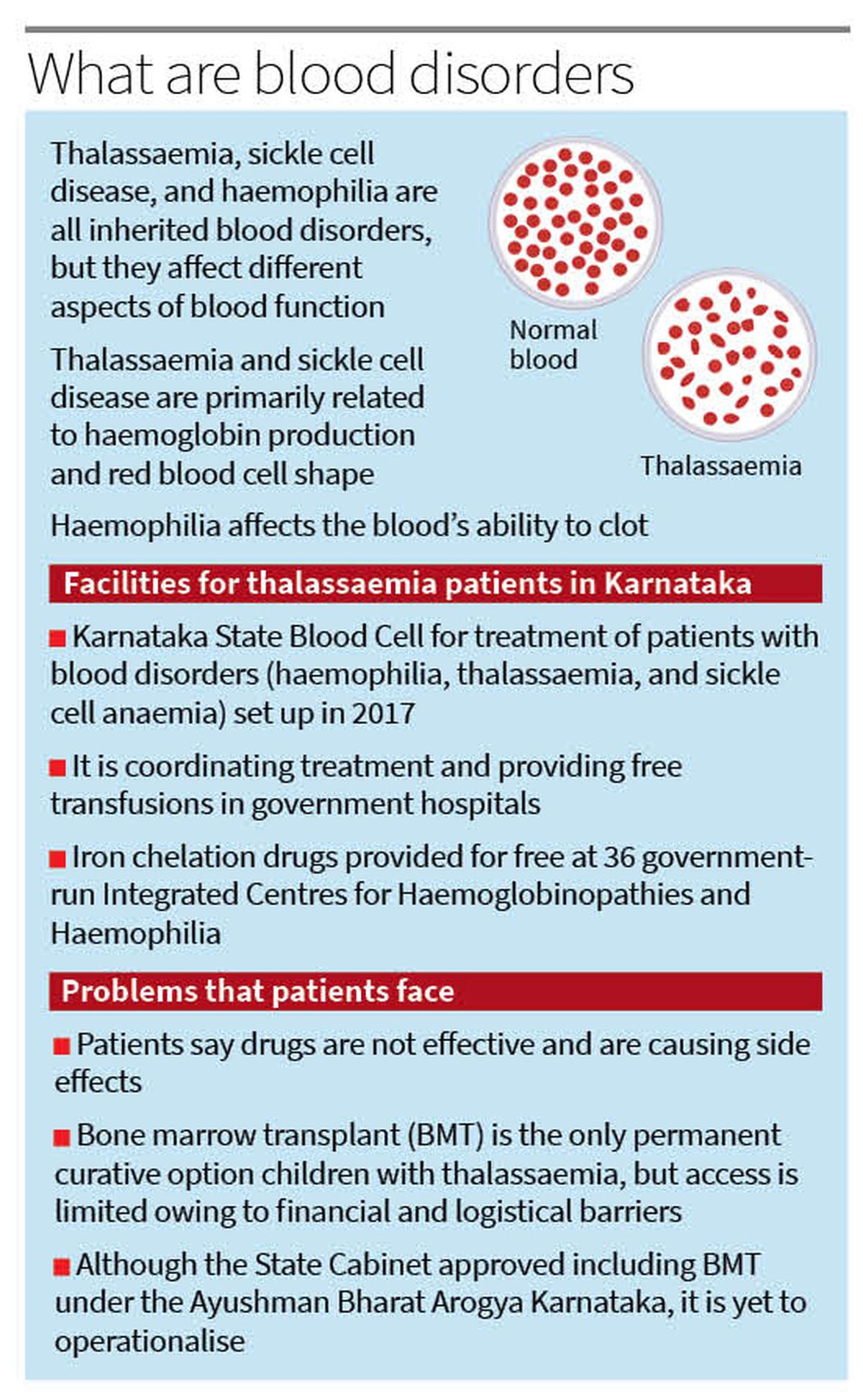

Bone marrow transplant offers the only permanent curative option for children with thalassaemia, but access remains limited due to financial and logistical barriers, according to experts.

| Photo Credit:

K. Bhagya Prakash

Access to drugs

These three are among an estimated 10,000 thalassaemia patients in Karnataka, a number that experts say is growing due to the lack of systematic screening and awareness. No government registry is available to document the number of people living with this disorder.

However, despite the growing burden, public health mechanisms remain fragmented. The State established the Karnataka State Blood Cell for the treatment of patients with blood disorders (haemophilia, thalassaemia, and sickle cell anaemia) in 2017. While this Blood Cell — operating under the National Health Mission (NHM) — is coordinating treatment and providing free transfusions in government hospitals, access to quality iron chelation drugs and specialised care remains uneven.

Although the State is providing thalassaemia drugs for free, short supply and lack of access to standardised drugs are proving costly for patients. Patients, who had been dependent on branded drugs by known manufacturers, are now getting only generic medicine manufactured by smaller pharma companies at the government centres. This is because there has been no response from big players to the tenders floated for procuring the drugs post-COVID-19 pandemic. Officials, who expressed helplessness, said according to norms, the tender has been allotted to the lowest bidder among those who participated.

According to data from the State Health Department, as many as 2,288 thalassaemia patients are registered with the 36 Integrated Centres for Haemoglobinopathies and Haemophilia (ICHH) run under the NHM. These centres, which also run day-care centres, provide free iron chelation drugs and blood transfusion services. Nearly half of the total registered patients have enrolled at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health (IGICH) in Bengaluru, which is the nodal centre.

While free transfusion services are also provided in all government blood banks, in Bengaluru, Rotary TTK Blood Bank’s Bangalore Medical Services Trustand a centre run by Sankalp, an NGO working for thalassaemia, are the two larger transfusion centres. Sankalp also runs a day-care for children at the IGICH and another one at Vasanthnagar, in the central part of the city, where blood transfusions are also done.

Lack of information

Patients from impoverished families, however, do not have sufficient information regarding the free treatment centres. They do not even know where to go to collect free medicines. Gagandeep Singh Chandok, president of the Thalassaemia and Sickle Cell Society of Bengaluru, says there is a need for quality drugs to be made available freely by the government.

“The availability of free iron chelation drugs is limited to one particular brand in government centres. However, this drug does not suit all patients. Although the Centre’s guidelines on haemoglobinopathies clearly say that options such as Desferal injection with infusion pumps should be made available, this is not happening,” he says.

“With the available drugs not effective, most patients have stopped taking them from the government centres. Several patients have developed side effects such as gastritis and a burning sensation in the throat, with no reduction in iron load. As these expensive drugs need to be taken every day, patients are forced to shell out around ₹20,000 every month. Many cannot afford this,” says Chandok.

Apart from the financial burden, thalassaemia patients also face stigma in their day-to-day lives. “This stigma is impacting our social, professional, and personal lives, leading to feelings of isolation, discrimination, and difficulty finding employment or establishing relationships. It is difficult to get leave for regular transfusions, making life difficult,” says Chandok.

Naveen Bhat Y., State Mission director, National Health Mission, says the government is committed to providing iron chelation drugs for free to increase the life expectancy, ensure a pain-free life, reduce disability, and uplift the standard of living of people with thalassaemia and their families. “There is no shortage of drugs. The centres need to submit an indent and take the drugs from the warehouse,” he says.

“It is a matter of concern if the drugs currently being provided to patients are not effective. If patients are developing any side effects or complications, they can inform their doctors at our ICHHs. While we have not received any complaints in this regard from patients or doctors in any of our centres, we will look into this issue and get the potency and efficacy of the drugs tested,” Bhat says.

He says that six labs in the State — IGICH in Bengaluru, K.R. Hospital in Mysuru, Wenlock District Hospital in Mangaluru, Gadag Institute of Medical Sciences, Ballari District Hospital, and Kalaburagi District Hospital — have been upgraded into nodal centres for blood disorders where high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) tests are done to detect thalassaemia.

There are an estimated 10,000 thalassaemia patients in Karnataka, a number that experts say is growing due to the lack of systematic screening and awareness. No government registry is available to document the number of people living with this disorder.

| Photo Credit:

K. Bhagya Prakash

Bone marrow transplant

Sunil Bhat, director and clinical lead, Paediatric Haematology, Oncology and Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Narayana Health, says bone marrow transplant (BMT) offers the only permanent curative option for children with thalassaemia, but access remains limited due to financial and logistical barriers.

Although the Karnataka State Cabinet approved the inclusion of BMT under Ayushman Bharat-Arogya Karnataka in January this year, it has not yet become operational.

However, free BMT is being offered to eligible children from the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe families. Last year, a seven-year-old son of a farmer from Kalaburagi underwent a sibling donor allogeneic BMT at the State-run Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology for thalassaemia. This is the only BMT done for thalassaemia here so far.

The cost of an autologous BMT ranges from ₹7 lakh to ₹15 lakh in private hospitals, and allogeneic BMTs are even more expensive. The stem cells in autologous transplants come from the same person who will get the transplant, so the patient is his/her own donor. The stem cells in the allogeneic transplants are from a person other than the patient, either a matched related or unrelated donor.

To improve access to transplantation for patients in need, DKMS Foundation India is funding a BMT centre operated by Sankalp India Foundation with the medical advice from Cure2Children on the premises of the Bhagwan Mahaveer Jain Hospital (BMJH) in Bengaluru. All the three are non-profit organisations.

D.M. Mohan Reddy, programme director, Sankalp-BMJH Centre for Paediatric Haemato-oncology and Bone Marrow Transplant, says that overall, 520 free BMTs have been done since 2013 under the programme. “We were earlier running the facility at People Tree Hospital and moved it to BMJH in 2021. Here, we have conducted 230 transplants so far with funding from the DKMS Foundation. For the last six months, we are also getting funds through the COAL India Project,” Reddy says.

India CEO of DKMS Patrick Paul says the country faces a shortage of stem cell donors, the core of bone marrow transplants. “Of the total 2,07,553 blood stem cell donors as per our database till April, as many as 42,939 are from Karnataka. Stem cell transplants play a vital role in treating blood cancers and blood disorders, including thalassaemia. However, because of genetic diversity, the chances of finding a perfect match within Indian registries are relatively low, emphasising the need for more donors,” he says.

Consanguineous marriages

Vasundhara Kailasnath, paediatric haematologist and BMT physician at Kidwai, says consanguineous marriages significantly increase the risk of a child inheriting thalassaemia. “This is because both parents are more likely to be carriers of the disease. Thalassaemia is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, meaning a child needs to inherit two copies of the faulty gene (one from each parent) to develop the condition,” she says.

“In Karnataka, studies have identified high prevalence rates especially in north Karnataka districts, apart from Hassan, Chitradurga, and Davangere. There’s also evidence of a high number of carriers and patients needing regular blood transfusions from these districts,” she says.

According to data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), Karnataka has the second-highest number of consanguineous marriages. While Tamil Nadu tops the list, where 27.9% of the female population is married to close blood relatives such as cousins, uncles, and brothers-in-law, Karnataka follows with 26.6%. The national average is far lower at 11%, according to the survey that was conducted between 2019 and 2021.

Besides, Karnataka has the highest number of women aged 15 to 49 married to a first cousin from their mother’s side. While 13.9% of the female population in the State is married to a cousin from the mother’s side, 9.6% is married to a cousin from the father’s side. Marriages to a woman’s second cousin and uncle were at 0.5% and 0.2%, respectively. About 2.5% of consanguineous marriages were to other types of blood relatives, and 0.1% to those who were previously brothers-in-law, according to the report.

Pointing out that people marrying within the family should get tested, Vasundhara Kailasnath says, “Carrier screening, prenatal testing (HPLC), and genetic counselling, apart from public awareness and education, can help reduce the risk of passing on the disorder from parents to children.”

(Names of patients and their parents have been changed on request.)

(Edited by Giridhar Narayan)

Published – May 09, 2025 07:12 am IST