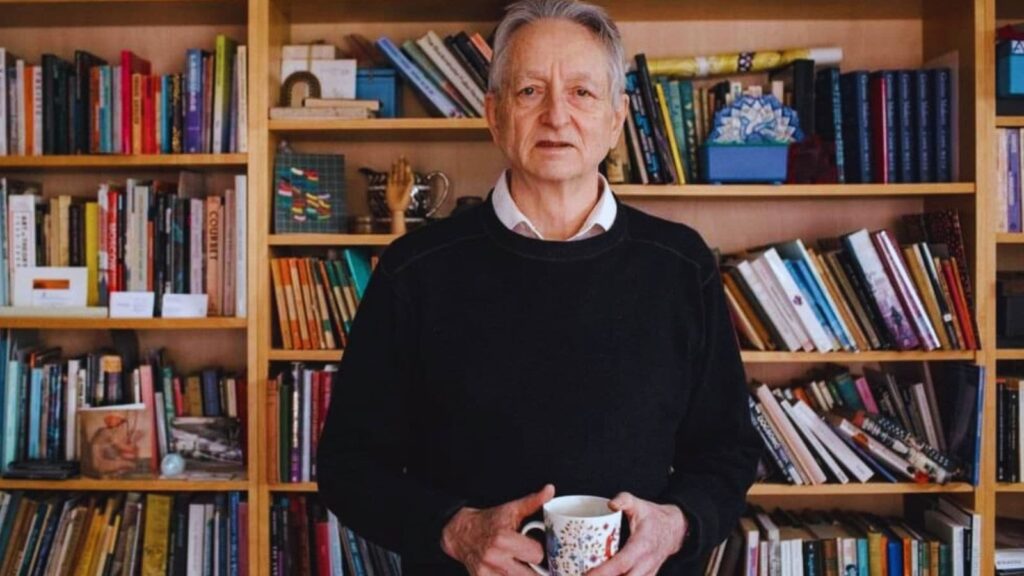

Geoffrey Hinton AI warning: “It’s digital. And, because it is digital, you can simulate a neural network on one piece of hardware, and exactly the same neural network on another piece of hardware, so you can have clones of the same intelligence,” said Nobel laureate Geoffrey Hinton, while explaining why he thinks artificial intelligence (AI) is already superior to humans.

Speaking to British entrepreneur Steven Bartlett on his podcast ‘The Dairy of A CEO’, the renowned computer scientist said that AI is already superior to humans in a number of domains. Hinton cited Chess where he thinks AI is ‘vastly superior’. He said that while GPT-4o knows thousands of times more than most people, the only difference is that these AI models can share their knowledge almost instantly across clones, whereas humans cannot. This, according to Hinton, makes AI immortal and fast learners.

In the one hour thirty-minute long interview, Hinton touched upon numerous concerns surrounding AI, the impact on jobs, and his hopes for the future.

On AI and joblessness

Talking about the threat of AI-induced joblessness, the scientist said that in the past, new technologies did not necessarily lead to widespread joblessness, rather new kinds of jobs were created. He cited the example of ATMs saying that when these machines were introduced, bank tellers did not lose their jobs. Instead, many of them moved on to more interesting tasks. “But I think AI is different. This is more like what happened during the Industrial Revolution, when machines started doing physical labour better than humans. You can’t really have a job digging ditches anymore, because a machine does it faster and more efficiently.”

Hinton believes that now AI is doing the same thing to intellectual labour. He said that for routine cognitive tasks, AI is simply going to replace people. He cautioned that although it may not mean full automation immediately, however, it may likely lead to far fewer people doing the same amount of work, but with the help of AI assistants. When Bartlett said some sections argued that AI will also create new jobs and things will balance out, the Dickson Prize winner said that this time it was different. “To stay relevant, you’d need to be highly skilled—able to do things AI can’t easily replicate. So I don’t think the old logic applies here. You can’t generalise from technologies like computers or ATMs. AI is in a different league.”

Even though the threat of job displacement is real, Hinton believes that AI in sectors like healthcare will be beneficial. “If we can make doctors five times more efficient, we could deliver five times more healthcare at the same cost. And people always want more healthcare if it’s affordable. In such cases, increased efficiency doesn’t reduce employment, it expands output.”

What are some of the biggest AI risks?

When asked what are the big concerns he has around the safety of AI, Hinton enumerated two different kinds of risks. He explained that firstly, there are risks that come from people misusing AI – that’s most of the risks, and all of the short-term risks. Secondly, there are risks that come from AI getting super smart and deciding it doesn’t need humans. When asked if this was a real risk, Hinton said that he is concerned mainly about the second kind of risk. “We’ve never been in this situation before. We’ve never had to deal with something smarter than us. That’s what makes the existential threat so difficult, we have no idea how to handle it, or what it’s going to look like. Anyone who claims they know exactly what will happen or how to deal with it is talking nonsense,” Hinton said.

Story continues below this ad

The 77-year-old went on to say that nobody knows how to estimate the probability that AI will replace us. He said that some, like his friend Meta’s Yann LeCun, who was a postdoc with him, believes that the probability is less than one per cent. “He thinks we’ll always be in control because we build these systems and we can make them obedient.” Meanwhile, he said, others like Eliezer Yudkowsky, believe the opposite. Hinton said that they are convinced that if anyone builds a superintelligence, it will wipe us out. “I think both of those positions are extreme. The truth is, it’s very hard to estimate the probabilities in between.”

What are the risks from bad human actors using AI?

Further into the conversation, Hinton went on to list the risks from bad human actors using AI. He said that cyberattacks have surged dramatically and according to him LLMs make phishing easier and he fears that AI will soon be able to generate novel and untraceable attacks. Another potential threat is that one angry person with the knowledge and access to AI could design deadly viruses triggering a warfare involving bioweapons. Moreover, there is also the threat of election interference. Hinton explained that AI could enable hyper-targeted political ads using personal data of voters. “If someone controls government databases, it becomes easy to manipulate voters.”

He informed the host that AI could lead to social division. Hinton said that algorithms like Facebook and YouTube could use AI to optimise engagement, meaning they could end up showing extreme, anger-inducing content that could likely reinforce bias driving people into echo chambers. There could be the possibility of autonomous weapons, essentially robots that decide to kill. The computer scientist explained that this could lower the cost of war, enabling countries to invade without sending soldiers, making wars more likely. Another critical issue would be job loss. He said that mundane intellectual labour such as legal assistants and call centres will be replaced. He used the analogy of industrial machines replacing muscles, and AI replacing the brain.

On being asked if AI will create jobs, Hinton said, “I’m not convinced. If it can do all mundane intellectual labor, there may not be new jobs left for humans. Some creative roles might remain for a while. But the whole idea of superintelligence is that eventually, it will be better at everything.” When Bartlett asked what people should do, the Turing award winner said that if AI works for us, then we will get more goods and services with less effort. But in case it decides that we are unnecessary, it may get rid of us. “That’s why we must figure out how to make it never want to harm us.” Similarly when asked what his message was for people who are wondering about their careers in the age of AI, Hinton said that it will be a long time before AI matches humans in physical skills. “So I’d recommend training as a plumber.”

Story continues below this ad

Is there something known as conscious AI?

To this, Hinton said that if one’s view of consciousness includes self-awareness, essentially the ability to think about their own thinking, then yes the machine would need to have that. “I am a materialist through and through, and I see no reason why a machine could not be conscious.” Consciousness is uniquely a human trait, and the host asked Hinton if he believes that machines could have the same kind of consciousness. He said, “I’m ambivalent about that at the moment. I don’t have a hard-line stance.” However he added that he thinks that once a machine has some degree of self-awareness, it begins to show consciousness.

“To me, consciousness is an emergent property of a complex system, not some mystical essence floating around the universe. If you build a system complex enough to model itself and process perception, you’re already on the path toward a conscious machine.”

Similarly, Bartlett mentioned that many people wonder if machines can think when a user is not interacting with them, if at all they have any emotions which are inherently known to be biological. To this, Hinton said he does not think that machines can think. However, once AI agents are created they will have concerns. He went on to cite the example of a call center saying that at present, human agents have feelings and emotional intelligence which are actually useful. “If the AI gets ‘embarrassed,’ it won’t blush or sweat. But it might still behave in a way that mimics embarrassment. In that case, yes—I’d say it’s experiencing emotion.”