With the U.S. terminating several research programmes, firing thousands of federal scientists, and cancelling important, high-value federal research grants— $8 billion already and further cuts of almost $18 billion next year for National Institute of Health (NIH), proposed cuts of about $5 billion next year to National Science Foundation (NSF), proposed cut of nearly 25% to NASA’s budget for 2026, and billions of dollars cut in grants to several universities — many U.S. scientists are planning to move to other countries.

According to an analysis carried out by Nature Careers, U.S. applications for European vacancies shot up by 32% in March this year compared with March 2024. A Nature poll found that 75% of respondents were “keen to leave the country”.

The European Union and at least a handful of European countries have committed special funding to attract researchers from the U.S. But the committed funding is dwarfed by the scale of funding cuts by the U.S., and the funding is already highly competitive in Europe, senior scientists from the U.S. moving to Europe in large numbers may not happen.

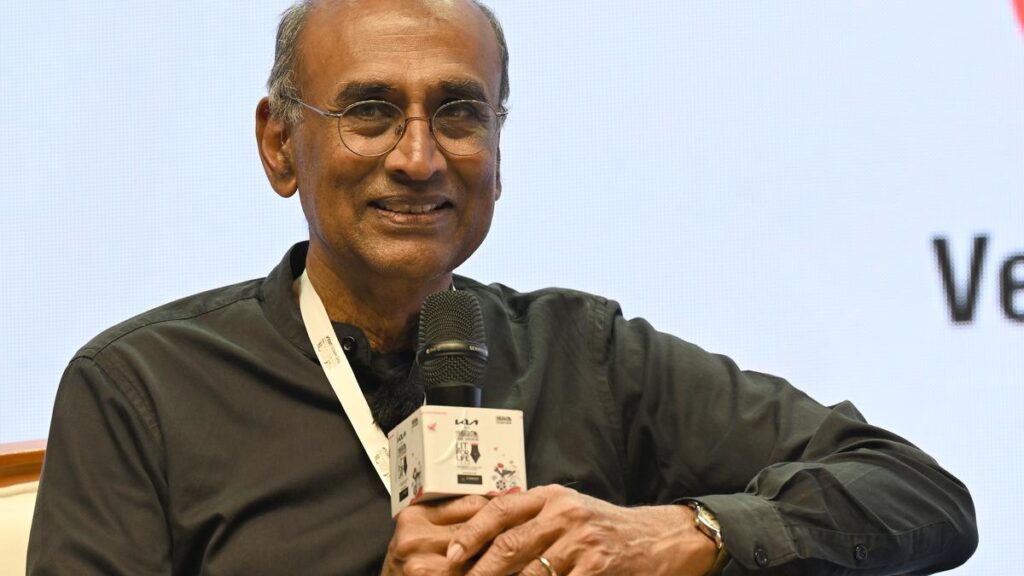

“There will be a few scientists who will move, but I do not see a mass exodus. Firstly, salaries in Europe are well below those in the U.S. Secondly, moving is always difficult both professionally and personally. Finally, the U.S. is still the pre-eminent scientific country, and that will be hard to walk away from. I say this as someone who actually did move from the U.S. to England over 25 years ago, with a salary that was just over half what I was making there,” Nobel Laureate Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, professor at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, U.K., says in an email to The Hindu.

In comparison, India has only a handful of institutions such as IISc, NCBS, TIFR, IISERs and IITs that can possibly attract U.S. scientists. According to him, even the renowned institutions in India are “world class only in some very specific areas”. “I do not see India as a general magnet for international science,” Prof. Ramakrishnan says.

Though funding for science in India has increased in absolute terms, the percentage of GDP allocated to R&D has actually reduced. India’s gross expenditure on R&D is estimated to be around 0.6-0.7% of GDP in 2025. Specifically, with long-term assured funding for basic research, which is an absolute necessity to attract researchers based in America, not guaranteed by existing programmes, can India take advantage of the situation in the U.S.? “India’s R&D investment as a fraction of GDP is much less than China’s and is about a third or less of what many developed countries have, and far below countries like South Korea. It will not be competitive without a substantial increase,” he says.

Lack of funding and infrastructure in India

About funding in general and funding for basic research in particular, Prof. Ramakrishnan says: “Neither the funding, the infrastructure nor the general environment in India is attractive for top-level international scientists to leave the U.S. to work in India. There may be specific areas (e.g. tropical diseases, ecology, etc) where India is particularly well suited, but even in these areas, it will be easier for scientists to do field work there while being employed in the West.” Given a choice between some European country or India, he strongly vouches Europe as “far more attractive as a scientific destination”.

Some of the key pain points Indian science faces are delayed release of funding every year, researcher scholars not being paid scholarship for as long as one year, and whimsical ways in which science policies are changed with little discussion with scientists. Even the Ramalingaswami re-entry fellowship, which aims to support the return of early-career life scientists with at least three years of international postdoctoral training, has faced abrupt policy changes. Currently, there are no national policies to attract senior scientists from other countries. “If India is serious about attracting Indian scientists abroad to return, it needs to provide far better incentives. China has shown that with sufficient investment and a stable commitment, it can be done,” he says.

Funding in India is available mainly from the government agencies such as DBT, ICMR, DST, SERB with negligible private funding. In 2021, the government announced ₹50,000 crore for Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF), which will replace SERB. In December 2024, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Science & Technology and Earth Sciences Dr. Jitendra Singh in a written reply to the Lok Sabha said that only ₹14,000 crore budgetary provision has been made by the government for 2023-2028. The balance ₹36,000 crore will be sourced through “donations from any other sources” including public and private sector, philanthropist organisations, foundations and international bodies. “In many developed countries, the ratio of private to public investment is almost two or more. In India, it is almost the opposite. This is really a failing on the part of Indian industry,” he says.

Years ago, Singapore succeeded in attracting senior scientists to move permanently or as visiting fellows. He attributes Singapore’s success in attracting talent from other countries to high salaries with low taxes, and excellent scientific infrastructure. On the societal front, Singapore, which is clean and well-run, with first-rate schools, health care, mass transit, and safety, has become the desired destination for scientists from developed countries, he adds. Scientists moved from Germany to the U.S. and other countries in the 1930s because they were in significant personal danger. “They and others moved to the U.S. because the U.S. could actually offer more facilities, higher salary, all in a free society. India does not offer any of these advantages,” he says.

Lack of better roads, cleaner air

To attract senior scientists from other countries and to encourage talented people already working in India, he stresses on two critical aspects — scientific and social. “India needs a strong, stable commitment to science, which means not only much more funding but also more stable funding, much better infrastructure and, just as importantly, insulating science from politics and excessive bureaucratic rules and regulations.” About the social factors, he says: “The other detriment to attracting scientists (especially non-Indians) from abroad is India itself. Today, well-off Indians have essentially seceded from public spaces in India. Today, the streets are filthy and full of trash, the sidewalks are not navigable, and the air is unbreathable in most cities… Which non-Indian would want that sort of life for themselves and their children?”

He is full of praise and appreciation for researchers in India contributing to science despite several challenges. “I have many scientific friends in India and I am always amazed by how they manage to do such good work in such difficult conditions, and yet be so cheerful. Young Indians are so bright and enthusiastic, but they are being let down by the country as a whole. India has a demographic dividend — it is one of the few large countries with a youthful population. However, this is a temporary advantage, and if India squanders it, it may find itself unable to be competitive in the future with other Asian countries and the West,” he cautions.

Published – June 19, 2025 12:02 pm IST