My granduncle, the late S.K. Varma, retired as news editor of The Indian Express in 1982. He held charge for almost two years but did not get the usual extension when he turned 58 because Ram Nath Goenka, apparently a crusader for justice, considered my granduncle a “union-wala”. Varma saheb, as his colleagues knew him, spent many a night during the Emergency (1975-77) sitting on the stairs inside Shastri Bhawan, waiting for the bureaucrats at V.C. Shukla’s Information & Broadcasting Ministry to pass his pages before they could go to press. He had reason to dislike Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, but his antipathy was far from the phoney propaganda we have been subjected to recently.

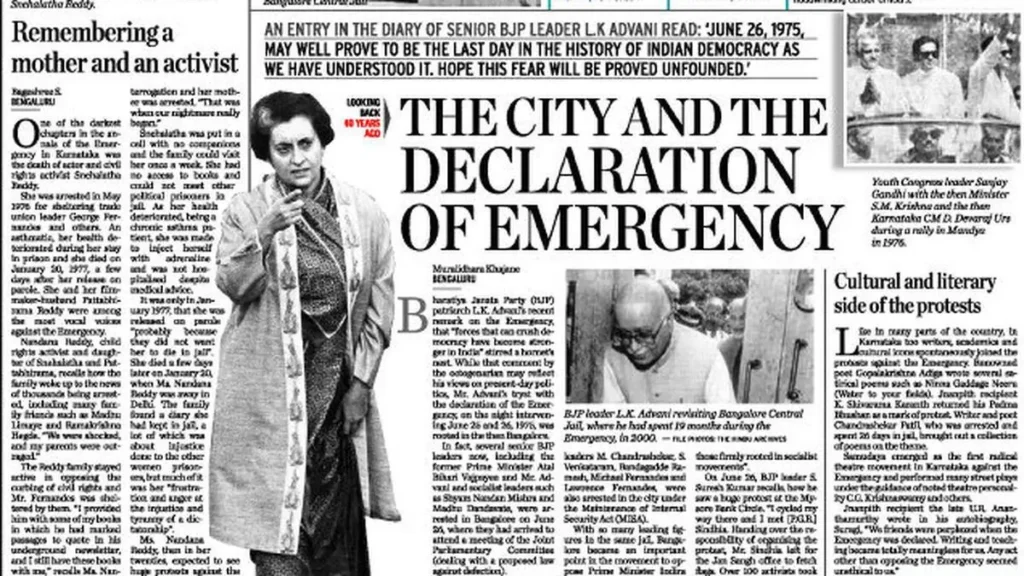

Nobody has openly declared an Emergency now, yet no one needs to get pre-publication approval because no one nowadays dares speak truth to power—former BJP chief L.K. Advani quipped that during the Emergency, the media was asked to bend but instead crawled. Today’s media cannot crawl because it is ensconced in the regime’s lap. Civil liberties do not have to be suspended because they exist only in name.

So, pardon me if I remember my granduncle, who stood for democracy against the British and the Emergency.

Also Read | Shubha Singh: A principled, perceptive journalist who moved through power with clarity and grace

Varma saheb was born in Muzaffarpur, Bihar, in 1922. In early 1943, he left for Patna to work at The Indian Nation under the late C.S.P. Rao. He fled Muzaffarpur because his eldest brother (my nana) prohibited him from participating in the Quit India movement in August 1942 (another brother was arrested). His mother emotionally blackmailed him into an arranged marriage during a visit home. He was having a secret scene with someone from the Women’s Auxiliary Corps of India in Patna, comprising tribal Christians and Anglo-Indians. My granduncle fled with both his wife and girlfriend to Lahore in 1945, where Rao saheb offered him a job at The Daily Herald, which was basically a Hindu mahasabha newspaper.

In Lahore, Varma saheb became pals with B.R. Chopra, a film journalist. He told me a story of a film party at the famous Faletti’s Hotel where he drank and found contemporary cine star Karan Dewan to be a bore. But not too long after, it was clear the country was being partitioned; they would have to leave Lahore.

Such was the tension that when Maulana Abul Kalam Azad held a press conference in 1946, Bhim Sen Sachar, a future three-time Punjab Chief Minister and Congress dissident who would be jailed during the Emergency, stood in as bodyguard. The Maulana was derisively called the “showpiece of the Hindus”. Varma saheb attended the meet and sat next to the Maulana, who offered him one of his “555” cigarettes from a tin.

Chopra invited Varma saheb to come along to Bombay and meet his hero K. Abbas; but my granduncle also got an invitation to join The National Herald in Lucknow, which Jawaharlal Nehru had voluntarily closed down in 1942 (so that it would be easier to reopen than if the government closed it), but reopened in 1945. Going to Delhi was not an option—it was at the time not considered an Indian city, but an English city. To Lucknow he went.

Varma saheb, the nationalist

Varma saheb was a nationalist. When Mahatma Gandhi visited Muzaffarpur in 1934 (the year of the Bihar-Nepal earthquake) my granduncle, then a boy, defied family orders and ran out to Chakkar maidan to hear the greatest political and social mobiliser India has ever known. When Gandhiji died in January 1948, my granduncle travelled to Delhi to be a part of the sea of humanity that witnessed his immersion.

At The National Herald, Prime Minister Nehru once dropped by, and Varma saheb got to see him up close. Feroze Gandhi, Indira’s estranged husband, was the Managing Director in the late 1940s and was a regular at the office. In the 1960s, Varma saheb joined the Express, where his career played out.

Whenever I visited Delhi as a youngster, I stayed with him. He lived the bachelor’s life in Lajpat Nagar, with longtime friend and Express news editor Piloo Saxena, and Piloo saheb’s nephews and niece. There was a daily evening rum-fuelled adda with political discussions, flared tempers, and pork sausages at hand. One night, there was a lot of shouting over Chairman Mao’s death, for instance. Listening to these hard-boiled journalists was a treat. No wonder when I returned to India, I started journalism and lived with my granduncle for a few years.

To me, it is obvious that the ongoing 50th anniversary of the Emergency, when civil liberties were suspended, is false in tone. It is merely lip service by the regime’s various panjandrums, who write purple prose and talk like windbags about the horrors of the Emergency. One gentleman has a book out, on the cover of which he is disguised as Sam Pitroda in a time machine, trying to be some swashbuckler when in fact he was never arrested or jailed. Their utterances ring hollow.

The Emergency lasted 19 months. No political prisoner was jailed longer than that; contrast that with student activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam, who have been in prison for nearly five years.

Also Read | Eyewitness to a withering republic

A few died in jail during the Emergency, like C. Chittibabu, a former Mayor of Chennai who in fact was shielding the present-day Chief Minister, M.K. Stalin, from a lathi charge; Chittibabu’s heart attack resulted. At least one RSS functionary, Pandurang Kshirsagar, also died in custody.

But they are small fries compared to 83-year-old tribal rights activist Stan Swamy’s inhumane treatment. He was repeatedly denied bail on medical grounds despite suffering from Parkinson’s disease. He died in jail. The regime’s crony capitalist friends, who found Stan Swamy a thorn in their sides as they snatch land and exploit it for private profit, would not have shed a tear.

Clearly, the lessons of the fights against the British and the Emergency were learnt by only the pigs that took over in George Orwell’s classic Animal Farm: that securing power only requires a further tightening of the screws.

Aditya Sinha is a writer living in the outskirts of Delhi.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/columns/emergency-indian-press-freedom-sk-varma-legacy/article69764611.ece