Growing up, sustainability for me was far from the luxury concept it has become today. It was a way of living that expressed itself in the simplest act of my mother taking quarterly trips to Khadi Gramodyog outlets and purchasing yards of pastel-coloured fabrics, which she would later tailor into razor-sharp shirts and mandarin-collared short-length tunics. Many years later, when I first arrived in Delhi, I remember being accosted by peers who would marvel at some of the pieces in my closet. The brand of Indian Middle-Class Motherhood, I’d chuckle internally.

“In Indian households, the word was not used, but it was always there as a concept,” chimes in Kavita Parmar, founder and creative director of the IOU Project and Xtant, an annual international festival celebrating heritage, textiles and craft. For Parmar, who began her career sourcing for major American brands, sustainability was a concept rooted in her heritage. She uses the example of a simple lungi (a kind of cloth wrapped around the waist the two ends of which are knotted together), which in most households makes the journey from being a garment, to a bedsheet, to a towel, and then finally a rag.

At a time when brands globally face the challenge of an ever-increasing consumption force, a fresh crop of Indian creatives are finding an urgent need to centre zero-waste policies and ethical production practices at the heart of their labels. For Ashita Singhal, founder of Paiwand Studio, sustainable fashion was in the everyday mundane. “Whether it was my grandfather’s dhoti or my mother’s sarees, everything was either passed down or used further,” she shares. In fact, it was her mother’s practice of paiwand lagana (repairing clothes) that inspired the name of the brand, with concepts of mending, reusing, and reimagining garments at its heart.

Unlike many in the industry, Singhal doesn’t view sustainability as an imposed moniker; rather, as a by-product of thoughtful design and responsible production. For her, it’s about authenticity — understanding local materials, and addressing local issues. Visiting the Sunder Nagar mill in Delhi, she discovered dusty looms and weavers abandoning their craft due to financial hardship. Singhal vowed to provide employment and preserve the craft of weaving, ensuring that handloom traditions would not be lost to time. “I was deeply moved by what I saw, and it solidified my resolve to work with and uplift these communities,” she says.

This sentiment is the philosophy at the heart of Sonam Khetan’s eponymous label. Launched in 2022, the brand only uses natural dyes, and avoids polyester and animal skins, reflecting Khetan’s vision of a brand that “cares” for the environment, the people who create the garments, and the customers who wear them. “It’s no longer possible to do anything, whether fashion or otherwise, without engaging in the defence of the biosphere,” she asserts.

Khetan’s collections are not dictated by fleeting trends but by a larger, timeless narrative. Her designs blend the richness of Indian craftsmanship with clean, minimalist silhouettes. Whether collaborating with Delhi-based artisans or hand-woven Himalayan wool, Khetan is dedicated to integrating regional and global influences into her pieces. Referring to a piece featuring embroidery inspired by NASA’s satellite map of India’s monsoon winds, she describes her work as not just “wearable art” but a medium of “storytelling”.

But like Khetan and Singhal, challenges galore for such homegrown labels who prioritise sustainability in the development of their brand identities. For Kriti Tula, founder of Doodlage, the higher cost of eco-friendly materials and sustainable production often discourages consumers. According to Khetan, working with materials like khadi silk and khadi cotton is not only more expensive but working with small, sustainable batches limits flexibility. Such challenges also have other spillover effects—raising issues of affordability in a price-sensitive market like India.

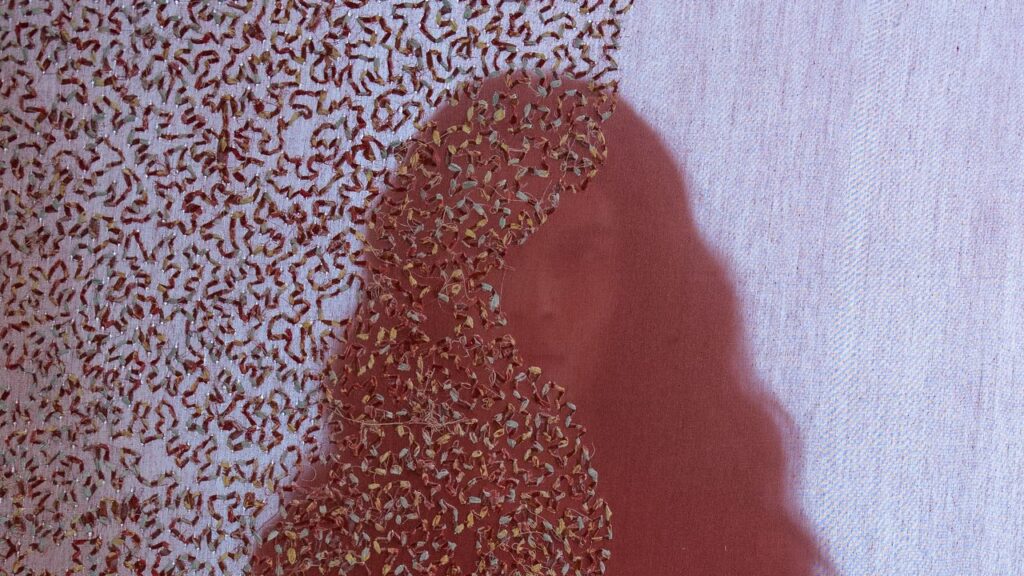

According to Karishma Shahani Khan, founder of the brand Ka-Sha, navigating affordability while maintaining the integrity of the product is a constant “balancing act.” Nonetheless, Khan remains committed to both the environmental and social aspects of sustainability, ensuring that artisans are given consistent work season after season to cultivate their craft. To this end, she has now launched a parallel, sister brand Heart to Haat, that repurposes every centimetre of fabric waste emerging from Ka-Sha’s production.

At Doodlage, Tula tracks the brand’s progress without relying on expensive certifications. Instead, her team spends hours sourcing locally, maintaining transparency in the supply chain, conserving natural resources and ensuring fair wages for workers. “Our ultimate goal is to integrate more advanced tools and benchmarks as we grow,” she shares, envisioning a future where the brand can continue to scale its sustainability efforts without compromising its values.

Denying binaries of luxury brand-positioning and industrial scaling, Parmar muses over the possibility of a business model that makes sustainable fashion emerge from its unaffordable niche corner. She imagines a patented design pattern from a maison, accessed through an affordable cost, and then hand-replicated by local artisans on customised garments. “It would be like listening to a Beatles song. It’s a dream of mine, but every single technology that’s required for it exists,” she adds with a barely concealed smile.