At the peak of her campaign against the devadasi system, Moovalur Ramamirtham Ammaiyar did the unthinkable: she chanted Sanskrit mantras at weddings, explained them in Tamil, and pointed out the anti-women essence in them. More than 80 weddings were held under her leadership. Moovalur’s campaigns did not just break the shackles of devadasi women but also propounded self-respect marriages.

In her handwritten manuscript My Life History, she noted: “Like one possessed, I started making derogatory speeches against the devadasi practice.”

But the feminist anti-caste icon’s story “has been swept under the carpet,” author Jeevasundari points out in the opening chapter “Hidden histories” of her book The Life and Work of Moovalur Ramamirtham Ammaiyar.

The Life and Work of Moovalur Ramamirtham Ammaiyar

By B. Jeevasundari; Translated by V. Bharathi Harishankar

Zubaan

Pages: 149

Price: Rs.495

The book is an outcome of the “Thisaidhorum Dravidam” (Dravidam in all directions) project announced by Tamil Nadu Textbook and Educational Services Corporation in 2021-22. The original work, in Tamil, written by B. Jeevasundari, a feminist researcher, has been translated into English by Bharathi Harishankar, vice chancellor of the Avinashilingam Institute for Home Science and Higher Education for Women.

The political trajectory of Moovalur life, meticulously documented, tells us that she was her own person in both the Congress party and the Dravidian movement. Her struggles to end the devadasi system were intertwined with her commitment to the national cause of independence, self-reliance, uplifting the lives of women, and importantly, her anti-caste politics.

Born to an abjectly poor family from the Isai Vellalar caste in 1883, Moovalur writes in Kudi Arasu magazine (December, 13, 1925) that she was “sold for Rs.10 and an old sari” to Achikannu, a devadasi, when she was only five.

Also Read | 1947: Madras Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication) Act passed

Growing up under the shelter and wings of Aachikannu, by the age of 10, Moovalur was well-trained in dance and music. Her proficiency in Sanskrit, quite uncommon for a non-Brahmin back in the day, helped her decode Vedic rituals. At 17, Moovalur received a marriage proposal from a 65-year-old “young” man who claimed to be in love with her. Going against her foster mother’s wishes, she rejected it. She fell in love with a partner of her choice, her music teacher, Suyambu Pillai, who complemented her principles. He also shunned blind superstitions and social beliefs. Their wedding had no religious rituals, acting as a forerunner to future self-respect marriages.

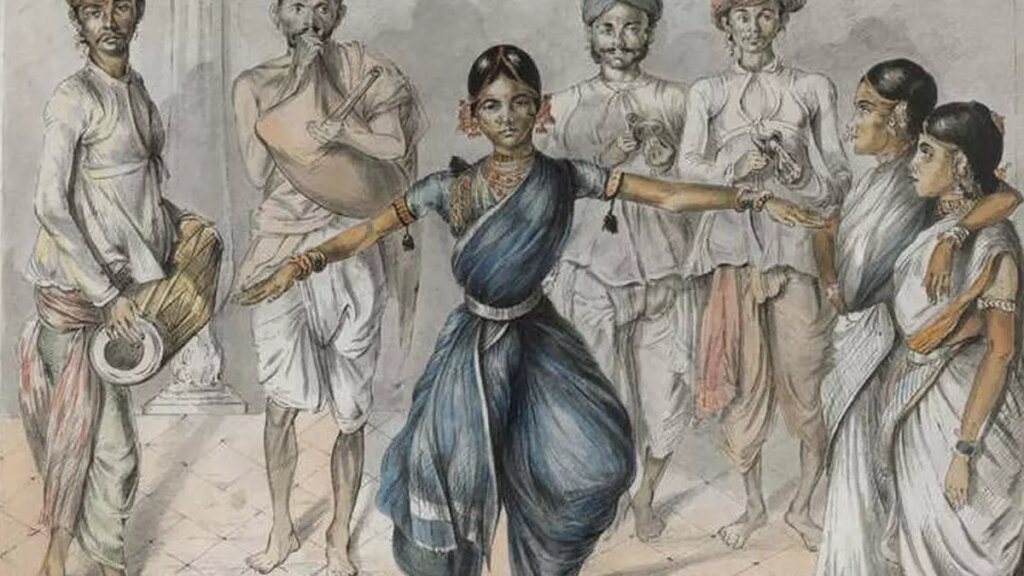

The exploitative devadasi system was an established practice in Thanjavur, Tirunelveli, Madurai, and Pudukottai in Tamil Nadu. Devadasis, the “handmaidens of god,” enslaved by hundreds of temples, were forced to have sex with social elites. It didn’t just stop at that: landlords used them for their assistance in auspicious ceremonies.

Jeevasundari records that no property rights were given to devadasis; they were only entitled to income generated from the property. Ironically and self-servingly, the system granted adoption rights to devadasi women in order to keep the community servile.

When the news of Moovalur campaigns against the devadasi system reached Gandhi, the Mahatma sent her a letter of appreciation. About 35 years later, appreciating her work, DMK founder C.N. Annadurai remarked, “When the late Gandhi was in search of women who would work for the social cause, he could find only Ammaiyar [Moovalur].”

Besides opposition from landlords, Brahmin priests, and powerful leaders, there was also pushback from the devadasi community against the abolition of the system; the community saw it as a threat to their livelihood, and feared the traditional dance form would fade away. The book, however, circumvents the reasons for their objection to the abolition and goes on to note that devadasi women eventually joined Moovalur’s Pottuaruppu Sangam or the anti-dedication association.

Moovalur managed to impress even Gandhi’s counterpart—Mohammed Ali Jinnah. When the British banned a flag march in Kakinada at the All-India Congress conference, she stitched a few flags together, wore it as a sari, and took part in the procession. When Jinnah asked about it, she responded, “It’s a crime to hold the flag in your hand but what can they do if it is worn as a sari?”

When Moovalur became a force to reckon with, she received huge support from the Congress: Thiru.Vi. Kalyanasundaram and “Periyar” E.V. Ramasamy insisted on creating a structured team for her campaigns. She financed the first Isai Vellalar conference all by herself: A remarkable feat, as her parents left behind no wealth, and there were no legal inheritance rights for women in her time.

When Periyar returned from his Soviet trip in 1932 with a deeper understanding of the role of economic freedom for one’s self-respect, he organised a meeting at his Erode residence, which came to be called the “Erottu Paathai” (The Erode way). Moovalur was also one among the political heavyweights—M. Singaravelar, P. Jeevanandam, Kuthoosi Gurusamy, Ramanathan, and others—who attended the meeting. She played a pivotal role in drafting the manifesto of the Self-Respect Movement.

When the Dravidar Kazhagam split and the DMK was formed in 1949, Moovalur asked Periyar “why can’t he name her as his heir?” Such was her agency and proximity to the social justice leader. Jeevasundari plugs the cardinal question at the very end of the chapter “Femininity is forever”: When people like Muthulakshmi Reddy, Ambujammal, and Neelavathi Ramasubramaniam who worked with Moovalur have been honoured by the government, why is she alone ignored?

She directs this question at the Congress, the Dravidian, and the women’s liberation movements, and asks them whether the reason behind leaving her out was that she did not have an upper-caste background.

Today, the people of Tamil Nadu remember Moovalur through the scheme launched under her name by the DMK in 1989, which initially provided marriage assistance to young women, and was later changed into an educational assistance scheme by the same government in 2022.

Only from the Chapter IV are the years of events specified, distinct from the previous chapters when readers have only Moovalur’s age to make sense of the timeline. Jeevasundari acknowledges these gaps and points out that only upon referring Moovalur’s handwritten memoir and articles published in Annai magazine, brought out by DMK minister Satyavani Muthu (one of the earliest Dalit leaders of the Dravidian party) was she able to sketch a clear picture of the icon’s formative years.

The translation of the narration and the original texts written by Moovalur relies on simple language. It maintains a formal tone. Staying true to her lines in the translator’s note, Harishankar keeps her translation “responsive to the original text in terms of its language and culture.”

Also Read | The Pioneers: Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy

Moovalur was also a prolific writer, and the book gives space to her political writings in the annexure. In her essay titled “Islamum Indhiyargalin Nilaimaiyum” (Islam and the Status of Indians), she argues how Aryan preachings damaged rational thinking, enslaving people in the name of caste. She boldly asserts that Tamil ideology and Islamic ideology are similar with a rider that it is not her aim to convert people.

In another article that pins hope on poet Bharathidasan to take the Tamil literary movement forward, she attempts to instil Tamil pride in readers and rues the introduction of Sanskrit words and Brahmanical slang in Tamil films. This critique continues to be voiced by Tamil scholars today.

The book richly supplements her writing on women’s education with the minutes of the meetings organised by the Mayavaram Women’s Welfare Association. The women of the association met regularly at Moovalur’s house in 1944-45 to debate social and political matters. The meetings, which began at the peak of WWII saw illuminating discussions on themes such as “Women’s duty during war,” “War and thrifty practices by women,” “The domestic life of ancient women,” among others.

Moovalur’s legacy lives on. Muthulakshmi Reddy—the first woman doctor in Tamil Nadu, the first Indian woman to be elected to the Legislative Council, the woman who introduced the Bill against the devadasi system—was influenced by Moovalur, according to writer V.R. Devika who authored Muthulakshmi Reddy: Path-breaking Woman in Social Reform and Medicine.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/books/moovalur-ramamirtham-devadasi-abolition-tamil-feminist-legacy/article69166998.ece