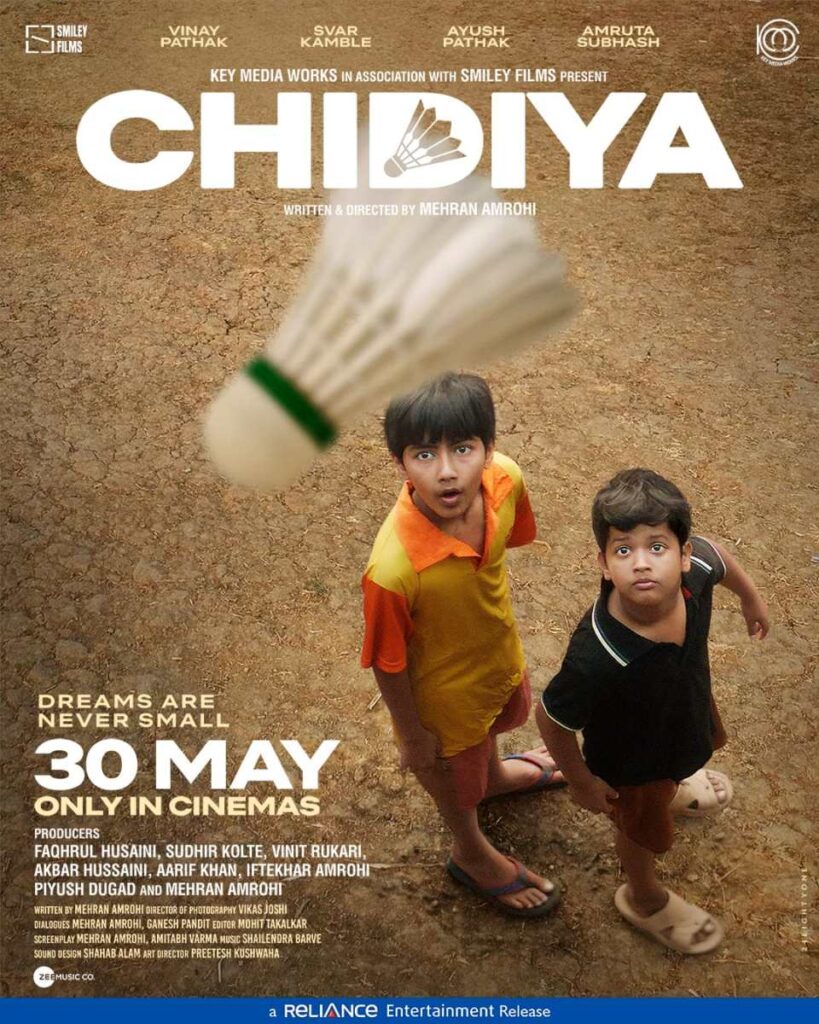

Writer-director Mehran Amrohi’s long-awaited film connects with the child in all of us, thanks to heartfelt performances by young actors Svar Kamble and Ayush Pathak

Rating: ⭐️⭐️⭐️💫 (3.5 / 5)

By Mayur Lookhar

What does a man need? Food, clothing, and shelter. A child, on the other hand, needs education and play. Writer-director Mehran Amrohi’s Chidiya (2025) is a gentle reminder that, regardless of social or economic background, education and play are every child’s birthright.

As the name suggests, Mehran is a distant relative of the late great filmmaker Kamal Amrohi. Unlike Kamal, Mehran has faced a long struggle. Chidiya has been a long time coming. After a special screening, the director revealed he filmed it before the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, the director’s IMDb page lists Chidiya as a 2016 film. With its story set in 2015, the film has clearly waited years for a theatrical debut — but better late than never.

Story

Set in 2015, Chidiya tells the story of two young brothers, Shanu (Svar Kamble) and Bua (Ayush Pathak), who live in a slum in Mumbai. Their father has passed away, and their mother, Vaishnavi (Amruta Subhash), is struggling to make ends meet. Forget school—she’s barely able to feed them two proper meals a day. Desperate, she turns to her brother Bali (Vinay Pathak), a seasoned spot boy, asking him to help find the boys some work on film sets. Though hesitant, Bali eventually agrees and gets them small jobs, mostly serving tea on set.

The boys clearly aren’t enjoying their time on set—until they see the film’s hero (played by Shreyas Talpade) playing badminton in a scene. It’s a sport they’ve never seen before, and they’re instantly curious. After they serve him tea, Talpade notices Shanu staring at a shuttlecock on the table. He asks the production executive if there are any extras. When told there are, he lets the boy keep one.

The boys get their hands on a shuttlecock and manage to find some cheap racquets, setting up a makeshift net and court in their humble neighborhood. But for one reason or another, they never actually get to play. When the film’s next shoot moves to Panchgani, the boys lose hope of ever playing the game.

Screenplay & Direction

The social message was clear from the start of this review. Amrohi has crafted a fairly engaging screenplay with strong writing and impressive performances from the two young actors. The title Chidiya is very thoughtful. Usually, chidiya (sparrow) is a metaphor for girls in feminist stories, but here, the film is about two little boys. More importantly, Chidiya also refers to the shuttlecock, often made from goose or duck feathers. If you clip a bird’s wings, it can’t fly. For a child, it’s like taking away their childhood when they’re denied the joy of sports and education.

Child labour is never acceptable, but it remains a harsh reality in highly populated and economically weaker countries. India has made progress, but many children like Shanu and Bua still end up working just to survive in a tough, unforgiving world. Mehran approaches the issue with care, clearly showing that child labour is wrong. In one scene, Bali reminds his sister Vaishnavi that it’s illegal and that the police wouldn’t be forgiving if someone reported it. Vaishnavi tells him no cop is going to feed her children.

To be clear, Vaishnavi isn’t pushing her sons into labour—she’s weighed down by poverty. When Bali hands her their first wage, there’s no pride or relief on her face, only helplessness. It’s a subtle, powerful moment that shows Amrohi’s maturity as a writer and director, even in his debut film.

Chidiya appears to take flight early on but slows down at times. The film gains momentum in the second half, where the children face even more despair, but Amrohi seems more in control during this part.

Acting

It’s always risky to tell stories like this, where endless trials and tribulations can bore impatient viewers. However, Amrohi has two brilliant child actors at his disposal. Both Svar and Ayush have likely grown since they first shot the film, which may be why they were kept out of the film’s limited publicity.

We remember seeing Kamble as Saif Ali Khan’s son in Chef (2017). Since Chidiya was likely filmed before that, his performance here is even more striking. Svar hasn’t just acted—he has truly lived Shanu’s story. He’s handsome, with a deeply expressive face. The constant struggle just to play badminton weighs heavily on him. Though he tries to keep his feelings inside, the boy can’t hold back when he tears down the makeshift net and court, convinced he and his brother will never get to play. Kamble shows a maturity beyond his years, and after such a powerful performance, we can only hope he continues to grow into an even better actor.

Being the elder, Shanu is the calmer one, while little Ayush Pathak is a boisterous boy—full of energy and talkative, yet still innocent. He’s curious about everything and often asks his mom, “How did I arrive in this world?” At birth, he was named Bhuvan, but his classmates later teased him by calling him Bua, a name that stuck so well even his mother uses it. Though his brother is caring, siblings have their bittersweet moments, and Bua often wonders why his mother, brother, and cousin sister Ishani (Hetal Gada) make him do the hard yards. This kind of sibling banter is something everyone can relate to.

Though he’s just a little boy, it’s Bua who leaves you speechless in a touching scene. While having lunch with their uncle Bali, the older brother sadly asks why their father left them so early. Little Bua then wonders why Bali, who is older than their father, didn’t die first. Bali explains that God calls loved ones home early. He expects the kids to accept this, but Bua suddenly asks, “If that’s true, then will we die before you too?” A stunned Bali can’t hold back tears, and the moment hits the viewer hard as well. At that point, many desi and traditional Indians would say, “Umeed karte hai ke aisa scene karne ke baad, Amrohi ya phir kisi aur ne set par in baccho ki nazar utari hogi.” Given their powerful performances, it’s fair to say Kamble and Pathak carry the film on their young shoulders.

While the child artistes are brilliant, one does wonder how a family struggling to make ends meet still manages to dress the children in fairly decent clothes. Then again, in 2025, it’s all about being presentable. For children who have quit school and are missing out on important years, perhaps director Amrohi could have included a scene where the boys actually learn the sport. Until then, they’re mostly just shown watching others play badminton from the sidelines.

From the young Pathak, we shift to the older one. Vinay Pathak, a North Indian, gives a sincere performance, though he doesn’t quite fit the role of a Maharashtrian character. Still, as Bali, he becomes the voice of the unsung spot dadas and the many humble workers behind the scenes on Hindi film sets. While we often assume Bollywood respects the dignity of labour, the film quietly reveals that this isn’t always the case. Bali isn’t alone in feeling undervalued—one lightman complains that the crew isn’t even served proper tea. The next day, Shanu brings him a larger glass, hoping it might earn him a small favour. These small but telling moments allow the film to subtly highlight real industry issues, unafraid to call out a chindi (stingy) producer.

Inaamulhaq shines as the local tailor who doesn’t walk straight. We’re not the best to judge, but perhaps years of tailoring have taken a toll on his back. He and another Muslim character subtly highlight Mumbai’s inclusive spirit and communal harmony.

Amruta Subhash often shines in such roles, and here too, she delivers a strong performance. While she can be tough on her children, Vaishnavi wouldn’t let anyone else bring harm to Shanu and Bua. Given her circumstances, you can’t help but admire her for standing by her kids despite all the trials and tribulations.

Technical aspects / Music

As the film is set primarily in a slum and features a few scenes at Kamal Amrohi Studio, there isn’t much scope for multiple locations. The music, though not particularly melodious, suits the context well. The song Sasura Mera Natka captures Mumbai’s inclusive culture, blending Hindi and Marathi lines in its mukhda (opening verse)—a lesson for those who tend to go overboard with linguistic pride.

The final verdict

Amrohi’s long struggle to bring this film to theatres is a true mark of resilience. Beyond its social message, it highlights the pure joy a child feels while playing a sport. Back then, there were no grand dreams—just carefree moments filled with happiness. Chidiya taps into that nostalgia, making it a well-intentioned film perfect for the whole family. Without giving anything away, the film’s penultimate scene is a beautiful reminder of where our children truly belong.

Watch the video review below.