When Anish Shah was taking charge at Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M), first as deputy managing director and group chief financial officer in April 2020 and then as the group CEO a year later, Anand Mahindra, who was stepping down from executive functions, told Shah: “There are no holy cows. You can change whatever you want.”

This was the first time since 1945, when the group was founded as Mahindra and Mohammed by KC Mahindra, JC Mahindra and Malik Ghulam Mohammed (Mohammed moved to Pakistan after 1947), that there was going to be a group head from outside the founding family. That came against the backdrop of troubled succession at the Tata Group and Infosys in the preceding few years.

But things turned out differently at M&M, even though Shah started by tackling the most ticklish issue at family-owned businesses: Exiting companies. His reasons were compelling.

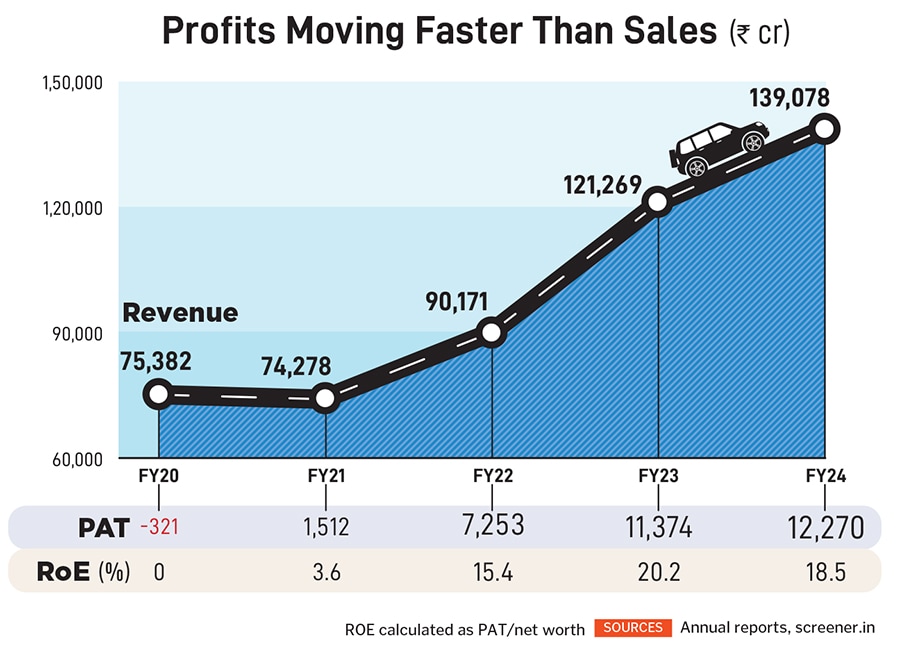

In FY20, losses from international subsidiaries stood at more than ₹5,200 crore, wiping out most of the profits coming from other parts of the group. Its market capitalisation had got eroded by about 70 percent between August 2018 and March 2020.

In the summer of 2020, Mahindra Group made a presentation to analysts in which it vowed to bring the losses closer to ₹300 crore. In the following year-and-a-half, it exited 15 loss-making units. The share price tripled in 12 months.

As things stand today, the group’s mainstay, the automotive business, has come out of its rough patch all guns blazing. As it embraces the electric technology, developed in-house, its products are being liked enough by customers to warrant a quadrupling of capacity in the last five years to about 60,000 units a month.

A substantial part of the increase in revenues has flowed into the bottom line—making its margins, at 19 percent, the best in the industry. Equally important is the less-talked-about farm equipment business, which has an industry-leading 43 percent market share. Its tractors outsell the combined numbers of the next five brands: TAFE, Sonalika, Escorts Kubota, John Deere and New Holland.

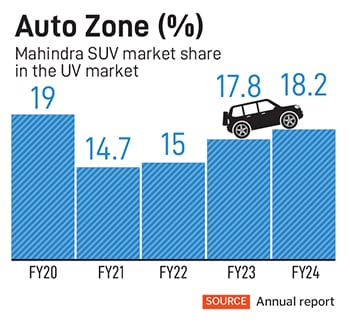

Part of the turnaround can be attributed to the rising tide, post-pandemic, of sports utility vehicles (SUVs), which have pushed sedans to the margins. And SUVs happen to be the core of M&M, boasting bestsellers such as Scorpio, Thar, Bolero, and a bevy of XUVs. But as Shah points out, M&M had the right products in place when the tide rose.

With its focus on SUVs intact, M&M became the second ranked carmaker in India in February, overtaking Hyundai. However, around the same time came job postings by Tesla Motor, suggesting it was ready to roll in India. This dented M&M’s share price.

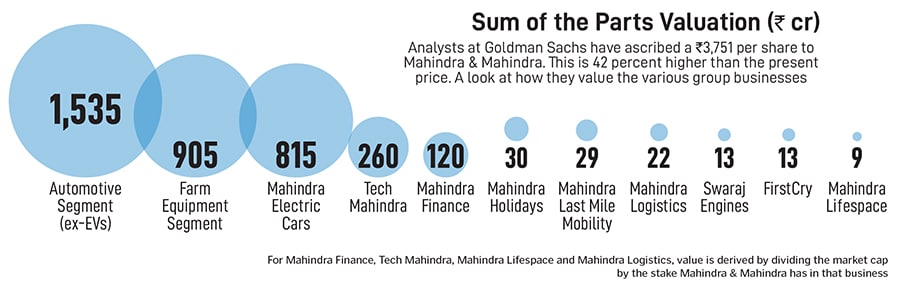

That probably means Shah has a two-fold task at hand. First, he must maintain the dominance of the auto and farm businesses by keeping the SUV pipeline strong while at the same time racing ahead during the inevitable shift to electric vehicles (EVs). It will warm his heart that a Goldman Sachs report dated February 17 estimates that M&M will have about 29 percent revenue share in the Indian electric car market in FY26 versus 7 percent in calendar year 2024.

Secondly, the other businesses—from information technology (IT) services to finance and real estate to renewable energy—require more attention. He has taken the challenge head on and set bold targets that envisage five-fold growth in some segments.

Also read: Forbes India CEO of the Year: M&M’s Rajesh Jejurikar, the risk taker

Remaking M&M

The 55-year-old Shah has an unhurried air about him, which is in sync with the boardroom on the sixth floor of Mahindra Towers, in Mumbai’s Worli area, where he met the Forbes India team at the end of February. Adorned with pictures showing the Bombay of yore—the Colaba Docks, Horniman Circle and the Clock Tower—contemporary business books, Veen water bottles sourced from Bhutan, and plenty of natural light, the rectangular room is functional, understated and unpretentious.

The stillness, though, cannot mask how deep the changes have been running under Shah. Soon after taking charge, he outlined his management philosophy under two broad tenets.

“First, do less, but whatever you do, do it well,” says Shah, in a measured and thoughtful manner. “Secondly, we outlined the behaviours we wanted everyone to exhibit: Being agile, bold and cooperative on a foundation of values.” Values, he cites, were also emphasised in a 1945 hiring advertisement by Mahindra and Mohammed.

The reemphasising of values was important, because when a new person, especially one from outside the owner family, takes charge, others wonder if the identity of the organisation will change. But Shah loved the Mahindra culture and had built relationships across its wings when he was the head of strategy. But most of all, he credits Anand Mahindra.

The reemphasising of values was important, because when a new person, especially one from outside the owner family, takes charge, others wonder if the identity of the organisation will change. But Shah loved the Mahindra culture and had built relationships across its wings when he was the head of strategy. But most of all, he credits Anand Mahindra.

“All the credit goes to Anand,” says Shah. “It is very difficult for anyone to step back and hand over the responsibilities, in this case in letter and spirit… he truly gave that empowerment.”

Anand Mahindra would be feeling vindicated. Last October, when the five-door Thar Roxx was launched, it garnered 176,000 bookings within an hour—more than four times the number of all SUVs the company makes in a month. Car enthusiasts, analysts, rivals and even company executives were stunned.

As Shah points out, “While the car market has hardly grown, SUVs have grown a lot faster.” Car sales stayed flat between FY21 and FY24, rising by a grand total of 9,000 units. In that period, SUV sales sprinted from 1.4 million to 2.5 million—an annual growth of 21.2 percent. Add to that the fact that the company took price increases and revenue rose faster, at 31 percent. Clearly, Mahindra is in the right place with its market share rising from 14.7 percent in FY21 to 18.2 percent in FY24.

Mahindra’s stock went up four times from the Covid lows, with customers waiting up to eight months to get their hands on the Thar. “There is a strong need to maintain a continuous presence [in SUVs] and Mahindra made sure they were not visitors to that segment,” says an analyst. He declined to be named, citing company policy, while pointing out that Tata Motors got distracted with the Indica and then the Nano.

But what M&M is doing is more than maintaining a continuous presence. Its SUVs have been known for being rugged and fuel-efficient. They can be repaired anywhere easily. But with electric, M&M is embracing vehicles that are desired more on the parameters of image and aspiration.

The story of farm sales, too, like autos, revolves around a consolidated market. Most districts have only two to three players. Products get pushed by dealers through their connections with sarpanches and wealthy farmers. For a long time, says Hemant Sikka, president—farm equipment sector, Mahindra’s market share hovered around the 40 to 41 percent mark. “We were just not able to break through,” he says.

Then suddenly this year several things started coming together. The first was product. Both Mahindra and Swaraj brands—the latter came with the acquisition of Punjab Tractors announced in 2007—entered the lightweight tractor segment. This allowed them to sell to orchard owners and rice farmers. The two brands competed in the same markets. The Swaraj range also saw a complete refresh in terms of engine, styling and features. Former India cricket captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni was brought in as brand ambassador. Some out-of-the-box thinking helped, one of them being prime time advertising push during cricket matches.

“When was the last time you saw tractors being advertised during a cricket match?” asks Sikka.

Also read: How India is going electric

Big cars & electric cars

India’s auto industry is working hard to challenge the notion that new technologies see winners from outside the incumbents. In two-wheelers, Bajaj Auto’s electric Chetak is clawing back market share from the likes of Ola. Tata Motors’ entry into the electric car business had a strong start with a 61 percent volume share in 2024.

In Mahindra’s case, it had a 7 percent market share with the electric XUV400. And though there is no doubt that Tesla is a formidable competitor, Shah appears unfazed by news of its impending entry. “I would invite you to try our new products,” he says, referring to the XEV9e and BE6, which received a total of 30,000 bookings in February. The company has targeted sales of 5,000 units per month and the eSUVs have been launched at the premium end.

If current trends persist, Mahindra EV sales could clock 8 percent of total volumes in FY26 but bring in 18 percent of revenue, according to the estimate by Goldman Sachs. That would allow the stock to either maintain its current multiple or trade at a higher multiple. The bank also estimates that the entry of Tesla in a market results in it growing for all players. The pie becoming larger would allow Mahindra to stave off the challenge from the likes of Tesla, BYD and Vinfast.

“I drove both the [M&M] vehicles and was pleasantly surprised,” says Chetan Maini, who founded India’s first electric car company, Reva, and later sold it to Mahindra. Maini now runs a battery swapping business, SUN Mobility. He cautions that it is too early to pass a long-term judgement and one can only be certain after six months of sales.

Electric car companies have over the years used two arguments to sell their products—the cars are good for the environment and that the total cost of ownership math shows EVs are cheaper to own. It is a message that has not got them very far.

“We decided to position our vehicles as objects of desire and around lifestyle—vehicles that just happen to be EVs,” says Ranjan Malik, co-founder at Primalise, a consulting firm that worked with Mahindra on the eSUV launch. The cars come packed with advanced driver assistance system, driver drowsiness indicator, self-parking, and Dolby Atmos sound systems—features that would be found in cars that are usually priced far above the ₹25-35 lakh tag the two M&M models carry. In effect, one must want to talk about the car at a party and not be sheepish about it being cheaper to drive.

The EV business has been spun off, giving the option of an independent stock market flotation in the years to come. For now, Temasek and British International Investment have invested in the four-wheeler electric mobility business at a valuation of ₹80,580 crore, which is about a fourth of the parents’ valuation.

Shah is keenly aware that he has a lot to prove and is keeping costs low. Some manufacturing steps like the paint shop will be common with ICE vehicles, and the assembly line is fungible. The reason why it has been housed in a separate company, Shah says, is because “the reality is that the electric vehicle business has a very different initial path to profitability”. He has not yet taken a call on battery manufacturing, choosing to work with providers, but making clear that the company is responsible for the performance of its products.

Commercial vehicles

A separate company houses the electric three- and four-wheeler commercial vehicle business, where 26 percent of the market has moved to electric. The company believes this market will move a lot faster to electric as the cost of operations matters more here.

Mahindra Last Mile Mobility (MLMM) has a clear first-mover advantage with a 45 percent market share. Here the cost of ownership argument is compelling, with electric three-wheelers being much cheaper to run than their internal combustion counterparts.

Suman Mishra, MLMM’s chief executive, estimates that over a five-year cycle the customer can save ₹4.5 lakh to ₹5 lakh despite the higher initial capital cost. “The amount of time the vehicle spends running or the uptime is the key, as is the availability of finance,” she says.

Again, investors have come into the business, albeit at a much lower valuation of ₹6,600 crore. After failures with the truck business, Mahindra Navistar, ICE two-wheelers, and SsangYong (although that allowed Mahindra to beef up its engineering chops), the evolution of the EV business is being keenly watched and could provide the next rating for the stock.

Growth gems

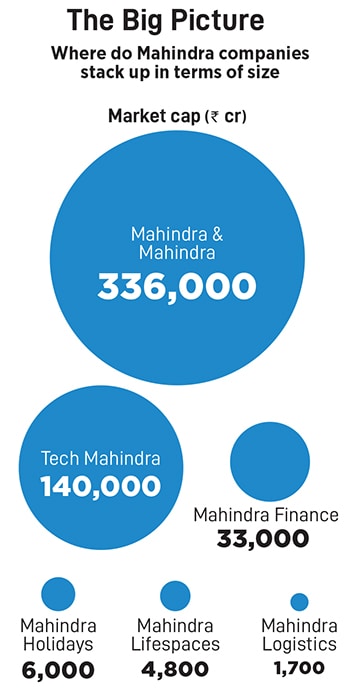

With the core auto and farm equipment businesses on a good wicket, Shah has set his sights on the other businesses in the group. Except for the 26 percent it owns in Tech Mahindra, Mahindra owns majority stakes in each of them. They brought in about a fifth of its ₹12,000 crore profits in FY24. If Shah can get this right, the overall numbers for M&M could look different in five years.

He has started by addressing personnel changes. Over the last two years, almost each of them has seen new leaders. CP Gurnani and Ramesh Iyer of, respectively, Tech Mahindra and Mahindra Finance superannuated. Leaders of Mahindra Lifespaces and Mahindra Holidays moved on to other jobs and were replaced.

Shah has earmarked IT services and financial services to achieve their full potential. Despite being around since 1986, when it was started as a joint venture with British Telecom, the IT business has been afflicted with low margins. At 12 percent or so, its margins are half of what a TCS, Infosys or Wipro makes.

Under new CEO Mohit Joshi, Tech Mahindra is said to be prioritising margins. But even with its FY27 target of 15 percent margins, the business would still be behind the leaders. Soaring visa costs or benched employees on account of a slackening of demand can send those calculations awry.

Mahindra Finance is of a similar vintage as Bajaj Finance. Sure, the two had different starting strategies. But Bajaj was able to capitalise on the rise and rise of personal loans, which, coupled with eKYC, gave it a sustainable moat. Its original business of being a monoline lender for Bajaj scooters has become a thing of the past. Today Bajaj has a ₹500,000 crore market cap, compared to ₹33,000 for Mahindra Finance.

“An underperformer,” an industry watcher calls it, pointing out that Mahindra Finance ends up going through an asset cycle every few years on account of the tractors and commercial vehicles it finances. “They lend a sub-prime product to a sub-prime borrower,” he says. It trades at 1.6 times book despite an AAA credit rating, compared to six times for Bajaj Finance.

The challenge for Mahindra Finance will be to diversify its book to add newer areas, such as housing loans, small business loans and loan against property. But that is easier said than done. These are extremely competitive businesses and diversifying requires new skills in assessing credit quality.

“Statistically [a transition] like this is more of an exception than the rule,” says Sanjay Bakshi, who teaches value investing and behavioural finance at FLAME University.

“Statistically [a transition] like this is more of an exception than the rule,” says Sanjay Bakshi, who teaches value investing and behavioural finance at FLAME University.

Mahindra Finance’s stock is trading where it did in 2018. Raul Rebello, its new CEO, was not available for an interview.

The real estate arm has tried many things. “They have not been able to build a strong product presence or geographical presence,” says Manoj Rajan, former partner at Piramal Capital.

The business did everything from mid to premium as well as affordable housing through its Mahindra Happinest brand. In a highly fragmented industry, the brand was unable to stand out.

To be fair, there are some things the real estate arm has done right. First, it has low debt. Second, it has healthy pre-sales while the market is still strong. Third, it has a healthy pipeline of projects in the redevelopment space in Mumbai. The project completion accounting standard means that a lot of the revenue and profits will be back ended—something the market has realised.

The stock has doubled its valuation to ₹4,700 crore in the post-Covid period. New CEO Amit Kumar Sinha’s plan is to take “calculated bets” with residential projects in Mumbai, Pune and Bengaluru.

The window of opportunity is open until the current up cycle in residential sales inevitably gives way to a down cycle. Once the velocity of sales slows, it becomes a challenge for real estate businesses to maintain profitability as buyers scout around for the best deal.

Shah, who has set a five-fold growth target for the smaller businesses, has already seen their valuation move up from $800 million to $4.2 billion. Some of these comprise newer unlisted businesses like Mahindra Susten, the renewable energy arm. The business has been around for more than a decade. In 2022 it adopted a five-fold growth strategy to develop 7,000 MW of assets. The business has already listed an Invit with the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan as a co-sponsor.

“We plan to build assets and operate them for a year before transferring to the Invit,” says Deepak Thakur, chief executive of Mahindra Susten. Importantly, he has chosen to not get into manufacturing, where frequent regulatory and technology changes can make for a minefield.

Numbers speak

If Shah manages to pull the smaller businesses along, he would have achieved what only a few leaders in corporate India have managed: Demonstrate their skills across a broad range of businesses and industries. The valuation of the group could also double or treble from the about ₹500,000 crore at present.

N Chandrasekaran of Tata Sons has done something similar by focusing on capital allocation and scale, although it could be argued that two of his biggest turnarounds are the cyclical auto and steel businesses which benefited from a favourable cycle.

At Mahindra, there have also been the occasional misfires, like the 3.53 percent stake bought in RBL Bank for ₹417 crore. The explanation offered was that the company planned to gain more knowledge of the banking business, though large corporate groups have not been given banking licences by the RBI after 1994, when the Hindujas set up IndusInd. Based on the current price of RBL Bank shares, the Mahindra stake would be sitting on ₹100 crore mark-to-market loss.

Those who work with Shah say his time as the head of strategy has given him a good understanding of how the group operates as well as its unique culture. But it is unclear how the old guard relates to him, though most of them are out.

Shah, who retains his US passport, is also said to be American-ised in his approach. Someone who has worked with him says it is “hard to read his mind”.

Overall, as a manager, Shah is seen to be driven by numbers. And his numbers speak for themselves.

The stock is nearly a 10-bagger from its Covid lows and Motilal Oswal recently recommended it in its list of ‘Bruised Blue Chips’—companies that went through a challenging time but are back on track.

“I want to keep our strengths, the entrepreneurial spirit, the discipline on capital allocation and the ability to execute intact,” says Shah.

He, too, is on track.

Source:https://www.forbesindia.com/article/leadership/anish-shah-is-breathing-new-lifes-into-mahindra-group-can-he-take-on-the-elon-musk-challenge/95702/1