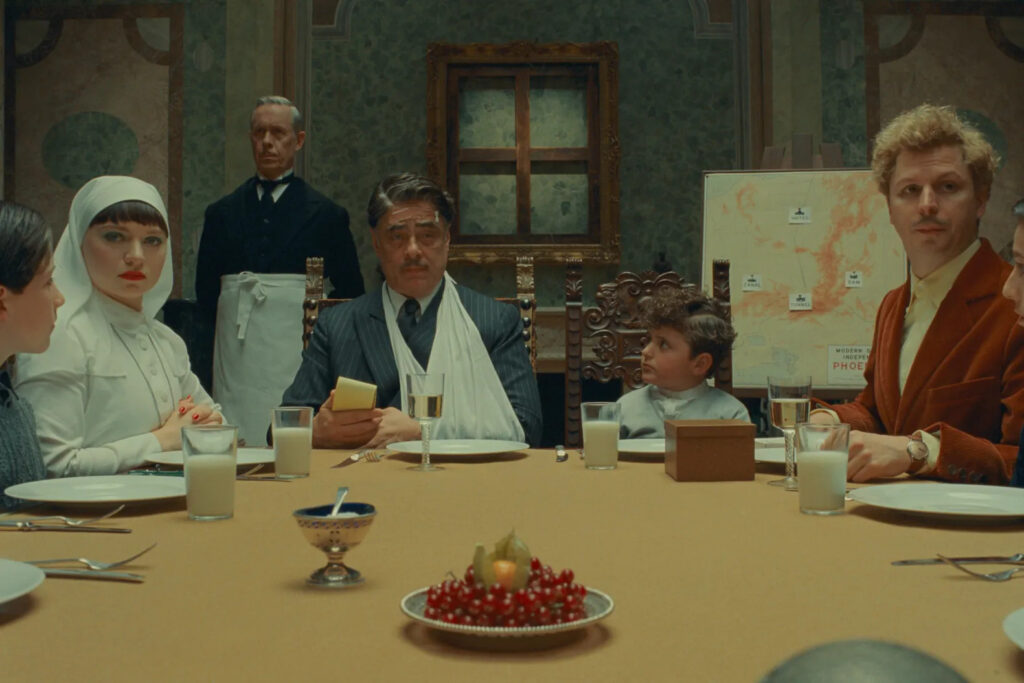

Mia Threapleton, Benicio Del Toro and Michael Cera in ‘The Phoenician Scheme.’

TPS Productions/Focus Features

There are dozens upon dozens of memorable eccentrics, delusional antiheroes, blustery authority figures, sad sacks, screw-ups and all-too-lovable schmucks that populate the 12 feature films and handful of shorts directed by Wes Anderson. It is safe to say that there’s nobody else like Anatole “Zsa Zsa” Korda in his back catalog. (The gentleman’s name alone, being a sui generis mixture of European gentry, old Hollywood callbacks and references to two different film directors, is pure chef’s kiss.) An international magnate of mystery, “a maverick in the fields of armaments and aviation,” and a celebrity business tycoon whose decisions have seismic effects on the mid-20th century’s global economy, Korda has no passport and no country he calls home. He simply resides on top of the world. As played by Benicio Del Toro with equal parts Shakespearean gravitas and Looney Tunes goofiness, he is an apex predator in a bespoke pinstriped suit. Even Royal Tenenbaum would step aside to let this titan of industry pass.

Such headline-making success breeds envy and enemies, of course, which is why a cabal of Korda’s rivals keep sabotaging his planes; when we meet Zsa Zsa, he’s just survived the umpteenth in-flight bombing and crash landing. One can only walk away from so many assassination attempts before their luck runs out. Which is why Korda is keen to secure his legacy. His master plan is twofold: First, he must convince his only daughter, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), to become the heir to his fortune; Korda doesn’t believe his nine young sons, who run the gamut from mischief-makers to nincompoops, are up to the task. The only caveat is that she must avenge his death should he perish. There are several problems with this initial stage, however, given that Liesl has been estranged from her father for years and believes he murdered her mother. Oh, and also, she’s a novitiate who wants nothing more than a convent to call her own.

The second part centers a vast infrastructure project involving a tunnel, a waterway and a “hydroelectric embankment.” Never mind the who, what, how, or why of it — dubbed “the Phoenician Scheme” and laid out via a series of intricate shoeboxes that speak more to the aesthetic favored by the famously fastidious filmmaker than anything else, this is Korda’s bid for immortality. Except the enigmatic Anti-Zsa Zsa committee that’s been bankrolling all those plane bombs have also just tanked the market in terms of the materials needed to build all of this. So Korda must trot the globe in order to ensure that his various investors can “cover the gap” vis-à-vis the funding. He’s decided to drag Liesl and Bjorn (Michael Cera), a tutor he’s hired from Oslo, along for company. Maybe this man who’s used to getting what he wants can convince the nun to get with the program. If Korda happens to bond with his offspring, that’s a bonus.

Both a continuation of Anderson’s highly imitable, endlessly meme-able strain of filmmaking — has any other name-above-the-title auteur of the last 30 years been so associated with one consistent, defining signature style? Please submit your answers via old-timey telegraphs — and an expansion of his thematic preoccupations, The Phoenician Scheme finds our man Wes in a somewhat pensive mood. Father figures have always loomed large in his work, dating back to his debut movie Bottle Rocket (1996), and along with Del Toro and cowriter Roman Coppola (no stranger to patriarchs with large shadows), he’s concocted one doozy of a screen dad. Korda thinks nothing of sequestering his nine sons in a mansion of their own across the street, so they’ll stay out of his hair. When several jump at the site of a praying mantis that Bjorn produces during a rare group lunch at his place, Korda barks, “Are we mice, or men?!” Liesl, for her part, is not happy to be summoned out of the blue after six years of no contact. She’s also aghast when she finds out he’s been spying on her from afar. “It’s not called spying when you’re the parent,” Zsa Zsa replies. “It’s called nurturing.”

But at the press conference at Cannes, where the film premiered last week, Anderson made a point of mentioning that he, Coppola and Del Toro are all raising daughters, and how that aspect factored into the schematics of his latest work. The director doesn’t need to fret about his legacy, but there’s an inherent worry about the responsibilities of fatherhood embedded into the DNA of this espionage-thriller-meets-ensemble-comedy. It’s easy to be anxious about being not just a dad but a bad dad, and while there’s zero sense that Anderson is exorcising personal demons — that’s not his style — the underlying feeling that Korda has come around entertaining the idea of some relationship with his spiritually questing firstborn too late in life is present even in the broader, more outré moments.

Not that The Phoenician Scheme isn’t playful, or filled with the surface pleasures so many of us have come to cherish about Anderson’s specific visual template. Longtime production designer Adam Stockhausen outdoes himself here, creating vivid worlds that run the gamut from exotic, Casablanca-style nightspots to underground-tunnel meeting spaces to treacherous jungle landscapes. Working with Bruno Delbonnel (Amelie, Across the Universe, Inside Llewyn Davis) for the first time, Anderson takes advantage of the French cinematographer’s facility with color, lighting, and an almost faded-Kodachrome look to this 1950s period piece. The cast, per usual, is vast and to die for: Jeffrey Wright delivers rat-a-tat dialogue as a sea captain living a true life aquatic; Benedict Cumberbatch rocks a bitchin’ Rasputin beard as Korda’s brother; Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston do a daffy double act as American businessmen who challenge Zsa Zsa and a prince played by Riz Ahmed to a trial by basketball; Scarlett Johansson shows up briefly as a cousin who runs a utopian commune; the always great Richard Aayode is a revolutionary who commits the sin of shooting up Mathieu Amalric’s chic dance club. A few straight-outta-Andrei Rublev vignettes in black and white suggest an afterlife in which God is played, naturally, by Bill Murray.

Rather, it’s that these set pieces and the supporting cast all serve to further buffer, goose and/or cast a different angle on the central relationship between Zsa Zsa and Liesl. And though most of The Phoenician Scheme is technically a three-hander, with Cera’s nebbishy academic adding to the screwball vibe (on a scale of one to Swedish Chef from The Muppets, his Oslo accent is roughly a six), this is really a two-person joint. Thank god Anderson cast the leads he did. As with a lot of great actors who can switch their pitches up at will, you probably take Benicio Del Toro for granted. The way he lends his alpha male industrialist both a sense of authority, a hint of a swindler’s con artistry, and a slight befuddlement mixed with buried pride over how Liesl stands up to him, all while keeping perfect comic time, is a prime example of why he’s forever courting generational GOAT status. And Threapleton, a relative newcomer, is a major find. It isn’t just that she can hold her own against her formidable scene partner; it’s that she works perfectly in tandem with him while distinguishing Liesl via a less-is-more performance. Told that her life will change irrevocably when she inherits her father’s fortune, the nun gives a barely discernible shrug. It’s like a silent-comedy routine in miniature.

The duo aren’t the only reason Scheme works as well as it does, but they do help lay an emotional foundation that gives Anderson room to build upon. The best of his movies — Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, Fantastic Mr. Fox, The Grand Budapest Hotel — find a way to gel a bigger-picture pathos with the idiosyncrasies, stylistic tics, tricks, and storytelling modes that has made him a beloved figure among both film nerds and discerning viewers desperate for watching big stars have fun. We’d rank this one right next to those. It ends on the closest thing to a simple life that this larger-than-life figure can imagine, taking its sweet time so you can savor the sublime nature of the moment that much more. You leave impressed that Anderson can still manage to do what his does best without succumbing to self-parody here. The blueprint may be familiar. But it’s still a pretty foolproof plan.

From Rolling Stone US.