Studies show that about 10 million people in India live with epilepsy. A significant portion of these cases, over 60%, begin in childhood. According to a study published in The Lancet, a 2021 review conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNESCO, which evaluated 87 school health interventions across Southeast Asia, found that none of these programmes addressed epilepsy.

This omission is particularly concerning in the Indian context, where epilepsy is officially recognised as one of the 23 health conditions covered under the Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK), the country’s flagship national school health initiative. The stark disconnect between policy and practice stresses the need for better systemic measures to address chronic neurological conditions within existing child health frameworks, say experts.

Despite its official inclusion, epilepsy is rarely identified or followed up during school health screenings. Unlike conditions such as anaemia, vision problems, or nutritional deficiencies routinely addressed in the school ecosystem — epilepsy remains off the radar for most frontline health workers and educators. The result is a missed opportunity for early detection, intervention, and long-term support for thousands of children.

What the study did

Addressing this critical gap, a multi-year, field-based study was conducted by a team of neurologists and public health experts at a few sites in Punjab — the study aimed not only to introduce epilepsy care into routine school health systems, but also to understand the barriers — structural, social, and educational — that hinder its recognition and management.

“Epilepsy is very common during childhood, particularly in India, due to birth complications and infections,” explained Gagandeep Singh, professor & head, neurology, Dayanand Medical College, Ludhiana, Punjab, and principal investigator of the study. Yet, children with epilepsy often go undiagnosed or receive delayed care, as seizures are either missed or misinterpreted.

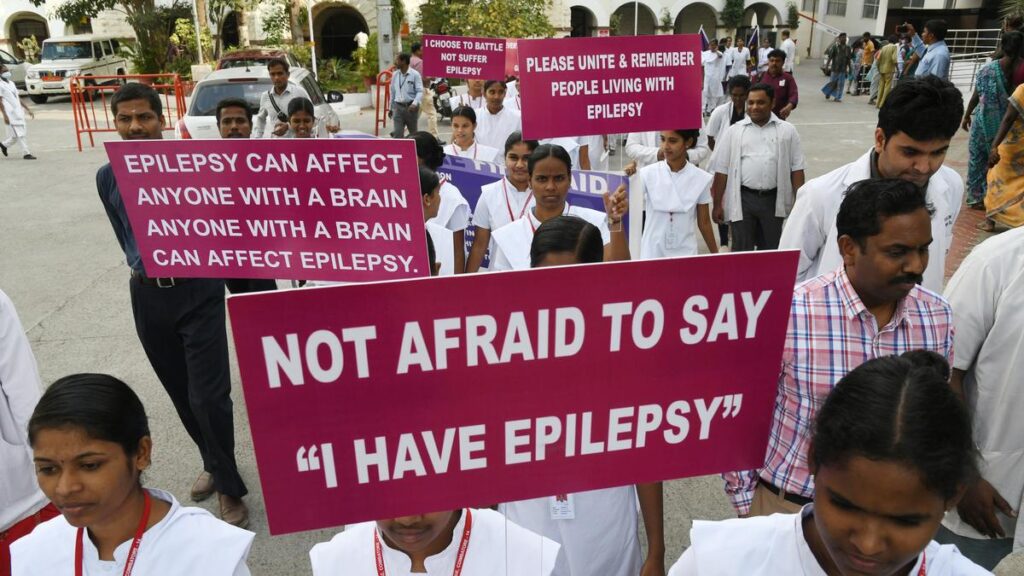

A major concern, as Dr. Singh pointed out, is the stigma and fear surrounding the condition. “Children are being pulled out of schools,” he said. “Either their parents are afraid, or teachers are unsure how to respond to a seizure episode.” The study panel also documented several cases where children faced social exclusion, bullying, or were forced to drop out following a visible seizure in class. The emotional and educational toll is significant, he pointed out.

One of the most significant findings was the lack of any standardised screening or referral mechanism for epilepsy under RBSK. Sulena S., professor, neurology, Guru Gobind Singh Medical College and Hospital, Faridkot, Punjab, the only government-appointed neurologist in Punjab and a lead member of the study said that while other conditions had checklists or standard operating procedures, epilepsy was relegated to anecdotal detection — if at all.

Despite the systemic gaps, Dr. Sulena observed a strong willingness to learn among the RBSK workforce. The team designed a comprehensive training strategy targeting all stakeholders — RBSK medical officers, school nurses, ASHA workers, Anganwadi staff, and teachers. The training focused on recognising common types of seizures, understanding what epilepsy is (and is not), learning appropriate first aid during a seizure, and most importantly, breaking down harmful myths. In several regions, epilepsy is still seen as a contagious or psychological condition — beliefs that exacerbate stigma and delay care.

Recommendations and interventions

To enable sustained change, the team developed educational modules specifically designed for diverse frontline workers and educators. “We created an ecosystem by involving every stakeholder,” said Dr. Sulena. The intervention included blended learning formats– offline workshops, digital videos, illustrated flipbooks, and community outreach sessions.

Modules covered seizure identification, myths and facts, psychosocial support, referral pathways, and classroom emergency response. One of the standout tools was an emergency response card that could be kept in classrooms — an easy-to-use guide for teachers during a seizure episode.

Sheffali Gulati, professor and child neurologist, Department of Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi emphasised that the introduction of seizure diaries — designed to be visual, simple, and interactive — as a critical step in tracking the frequency and nature of seizure episodes in children. “These diaries help children living with epilepsy and their parents,” noted Dr. Gulati. She also pointed out that emergency care procedures, such as CPR and seizure first aid, offer multiple benefits and are valuable for everyone — not just individuals within the epilepsy community.

Impact and future possibilities

Early results from the pilot sites have been encouraging according to the study panel. Teachers have reported greater comfort in managing seizures. Parents have shown improved follow-through with referrals. And, importantly, more children with suspected epilepsy are entering the formal care system rather than falling through the cracks.

The research team is now working on a mobile application to further support awareness, early detection, and continued learning. The app will include multimedia learning materials for children, families, and community workers, along with referral mapping tools to locate nearby neurology support.

This initiative is part of a broader multi-centre project with three operational field sites and two advisory centres. The aim is to create a replicable, scalable model that integrates epilepsy into the national school health architecture as a core priority.

Bridging health and education for inclusive care

“For childhood epilepsy management, we must create a strong ecosystem where all stakeholders — schools, parents, health workers — work together,” emphasised Dr. Sulena. The findings make it clear: epilepsy cannot remain a hidden condition in India’s school health narrative.

The study’s key takeaway is not just the need for awareness, but the importance of dismantling the silos between education and health systems, said doctors. Without that integration, children living with epilepsy risk being left out of both learning and care.

Published – May 17, 2025 07:00 pm IST