Culture reporter at Sheffield Documentary Festival

Fish+Bear Pictures

Fish+Bear PicturesTo say China’s women are outnumbered would be an understatement.

With a staggering 30 million more men than women, one of the world’s most populous countries has a deluge of unattached males.

The odds are heavily stacked against them finding a date, let alone a wife – something many feel pressured to do.

To make matters worse, it’s even harder if you’re from a lower social class, according to Chinese dating coach Hao, who has over 3,000 clients.

“Most of them are working class – they’re the least likely to find wives,” he says.

We see this first-hand in Violet Du Feng’s documentary, The Dating Game, where we watch Hao and three of his clients throughout his week-long dating camp.

All of them, including Hao, have come from poor, rural backgrounds, and were part of the generation growing up after the 90s in China, when many parents left their toddlers with other family members, to go and work in the cities.

That generation are now adults, and are going to the cities themselves to try to find a wife and boost their status.

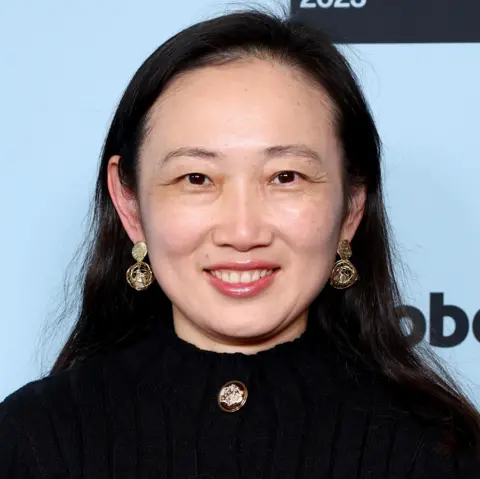

Du Feng, who is based in the US, wants her film to highlight what life is like for younger generations in her home country.

“In a time when gender divide is so extreme, particularly in China, it’s about how we can bridge a gap and create dialogue,” she tells the BBC.

Fish+Bear Pictures

Fish+Bear PicturesHao’s three clients – Li, 24, Wu, 27 and Zhou, 36 – are battling the aftermath of China’s one-child policy.

Set up by the government in 1980 when the population approached one billion, the policy was introduced amid fears that having too many people would affect the country’s economic growth.

But a traditional preference for male children led to large numbers of girls being abandoned, placed in orphanages, sex-selective abortions or even cases of female infanticide. The result is today’s huge gender imbalance.

China is now so concerned about its plummeting birth rate and ageing population that it ended the policy in 2016, and holds regular matchmaking events.

Wu, Li and Zhou want Hao to help them find a girlfriend at the very least.

He is someone they can aspire to be, having already succeeded in finding a wife, Wen, who is also a dating coach.

The men let Hao give them makeovers and haircuts, while he tells them his questionable “techniques” for attracting women – both online and in person.

But while everyone tries their best, not everything goes to plan.

Fish+Bear Pictures

Fish+Bear PicturesHao constructs an online image for each man, but he stretches a few boundaries in how he describes them, and Zhou thinks it feels “fake”.

“I feel guilty deceiving others,” he says, clearly uncomfortable with being portrayed as someone he can’t match in reality.

Du Feng thinks this is a wider problem.

“It’s a unique China story, but also it’s a universal story of how in this digital landscape, we’re all struggling and wrestling with the price of being fake in the digital world, and then the cost that we have to pay to be authentic and honest,” she says.

Hao may be one of China’s “most popular dating coaches”, but we see his wife question some of his methods.

Undeterred, he sends his proteges out to meet women, spraying their armpits with deodorant, declaring: “It’s showtime!”

The men have to approach potential dates in a busy night-time shopping centre in Chongqing, one of the world’s biggest cities.

It’s almost painful to watch as they ask women to link up via the messaging app WeChat.

But it does teach them to dig into their inner confidence, which, up until now, has been hidden from view.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Zheng Mu, from the National University of Singapore’s sociology department, tells the BBC how pressure to marry can impact single men.

“In China, marriage or the ability, financially and socially, to get married as the primary breadwinner, is still largely expected from men,” she says.

“As a result, the difficulty of being considered marriageable can be a social stigma, indicating they’re not capable and deserving of the role, which leads to great pressures and mental strains.”

Zhou is despondent about how much dates cost him, including paying for matchmakers, dinner and new clothes.

“I only make $600 (£440) a month,” he says, noting a date costs about $300.

“In the end our fate is determined by society,” he adds, deciding that he needs to “build up my status”.

Du Feng explains: “This is a generation in which a lot of these surplus men are defined as failures because of their economic status.

“They’re seen as the bottom of society, the working class, and so somehow getting married is another indicator that they can succeed.”

We learn that one way for men in China to “break social class” is to join the army, and see a big recruitment drive taking place in the film.

Fish+Bear Pictures

Fish+Bear PicturesThe film notably does not explore what life is like for gay men in China.

Du Feng agrees that Chines society is less accepting of gay men, while Dr Mu adds: “In China, heteronormativity largely rules.

“Therefore, men are expected to marry women to fulfill the norms… to support the nuclear family and develop it into bigger families by becoming parents.”

Technology also features in the documentary, which explores the increasing popularity of virtual boyfriends, saying that over 10 million women in China play online dating games.

We even get to see a virtual boyfriend in action – he’s understanding, undemanding and undeniably handsome.

One woman says real-life dating costs “time, money, emotional energy – it’s so exhausting”.

She adds that “virtual men are different – they have great temperaments, they’re just perfect”.

Dr Mu sees this trend as “indicative of social problems” in China, citing “long work hours, greedy work culture and competitive environment, along with entrenched gender role expectations”.

“Virtual boyfriends, who can behave better aligned with women’s expected ideals, may be a way for them to fulfil their romantic imaginations.”

Du Feng adds: “The thing universally that’s been mentioned is that the women with virtual boyfriends felt men in China are not emotionally stable.”

Her film digs into the men’s backgrounds, including their often fractured relationships with their parents and families.

“These men are coming from this, and there’s so much negative pressure on them – how could you expect them to be stable emotionally?”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesReuters reported last year that “long-term single lifestyles are gradually becoming more widespread in China”.

“I’m worried about how we connect with each other nowadays, especially the younger generation,” Du Feng says.

“Dating is just a device for us to talk about this. But I am really worried.

“My film is about how we live in this epidemic of loneliness, with all of us trying to find connections with each other.”

So by the end of the documentary, which has many comical moments, we see it has been something of a realistic journey of self-discovery for all of the men, including Hao.

“I think that it’s about the warmth as they find each other, knowing that it’s a collective crisis that they’re all facing, and how they still find hope,” Du Feng says.

“For them, it’s more about finding themselves and finding someone to pat their shoulders, saying, ‘I see you, and there’s a way you can make it’.”

Screen Daily’s Allan Hunter says the film is “sustained by the humanity that Du Feng finds in each of the individuals we come to know and understand a little better”, adding it “ultimately salutes the virtue of being true to yourself”.

Hao concludes: “Once you like yourself, it’s easier to get girls to like you.”

The Dating Game is out in selected UK cinemas this autumn.