The estimated dementia prevalence in India is 7.4% among adults aged 60 and older. This translates to about 8.8 million Indians currently living with dementia. The prevalence is projected to increase significantly in the coming years, with estimates suggesting a rise to 1.7 crore (17 million) by 2036.

And it is also increasingly recognised in India as a condition far more complex than memory loss. Dementia represents a progressive decline in cognitive abilities, including language, executive functioning, behaviour, and the capacity to perform daily tasks. Alzheimer’s disease remains the most well-known form of dementia, but it is only one of many. Indian clinicians are now focusing on comprehensive evaluations to identify reversible causes, clarifying diagnoses using advanced biomarkers, and staying informed about global advances in therapy — all while staying grounded in clinical realities and patient context.

Identifying reversible causes — a health priority in dementia care

According to Prabash Prabhakaran, director and senior consultant- neurology, SIMS Hospital, Chennai, dementia is often misunderstood as only memory loss, whereas one of the earliest signs could be executive dysfunction –such as a person forgetting how to prepare a familiar dish . He also emphasises the importance of looking for apraxia, which is the loss of learned motor skills, along with changes in gait and bladder control. A distinctive pattern like “magnetic gait,” where a person shuffles slowly and cannot lift their feet properly, may offer clues pointing to specific subtypes such as Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Even in patients with clear signs of cognitive decline, Dr. Prabhakaran warns against over-reliance on imaging or biomarker tests in isolation, stressing that without a robust clinical picture, these tools can mislead more than help.

One of the most critical steps in dementia care in India is to rule out reversible causes before settling on a diagnosis like Alzheimer’s. This clinical vigilance ensures that treatable conditions are not missed. For instance, vitamin B12 deficiency is a common cause of cognitive issues, especially among vegetarians, and can be easily corrected with supplements. Hypothyroidism is another frequently overlooked condition that can mimic dementia and is reversible with thyroid hormone replacement.

Dr. Prabhakaran shares that cases of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus — where dementia presents alongside gait instability and bladder dysfunction — can sometimes be reversed almost miraculously by draining around 30 ml of cerebrospinal fluid. There are also rarer possibilities like autoimmune dementia, which constitutes about two to three percent of cases. In such instances, antibody testing for approximately 23 known markers is now available in India. Familial dementia and vasculitis-related cognitive disorders also fall into this category of conditions where early detection can dramatically change outcomes. As Dr. Prabhakaran puts it, “Even if just one patient benefits from identifying a reversible cause, the clinical effort is worth it.”

Clinical evaluations to rule out health risks

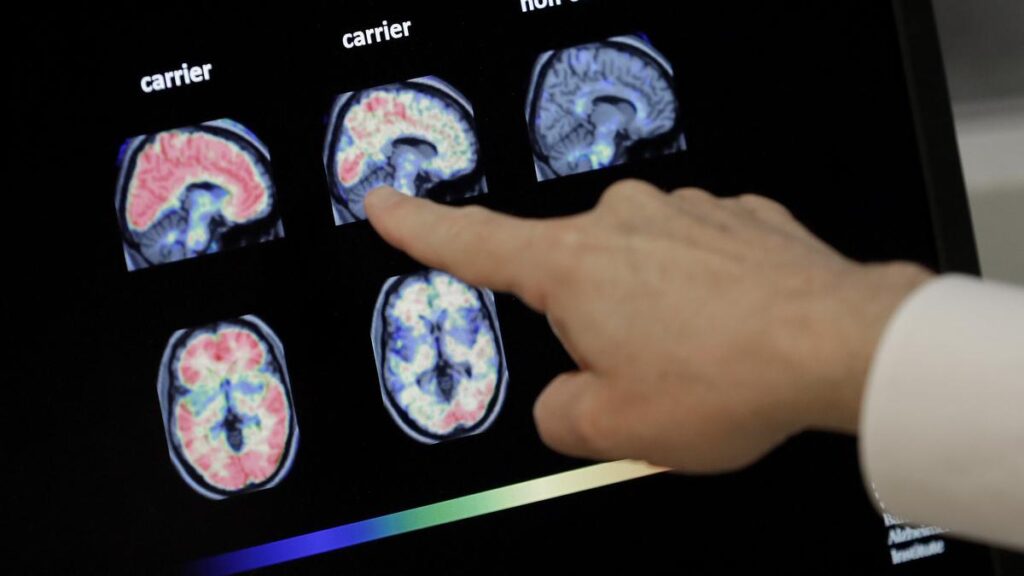

Imaging continues to be a helpful tool, not for confirmation but for exclusion. MRI scans are used to rule out brain masses, hydrocephalus, and vascular insults. While certain patterns of brain atrophy, particularly in the temporal and parietal lobes, may suggest Alzheimer’s disease, these findings are supportive rather than definitive. FDG-PET scans, which measure glucose metabolism, can reveal hypometabolism in specific brain regions, often correlating with suspected Alzheimer’s pathology. However, PET scans are advised only when there is already a strong clinical suspicion — they are not used as screening tools.

A major advancement in recent years is the use of blood-based biomarkers that measure levels of tau protein and beta-amyloid — proteins central to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. These are available in India but remain expensive and are not part of routine diagnostics. Dr. Prabhakaran explains that these tests are best used in specific scenarios: when the clinical presentation is ambiguous, when there is mild cognitive impairment, or in cases of early-onset or rapidly progressing dementia. He cautions against using biomarkers indiscriminately, underscoring that their role should always be hypothesis-driven.

Srividhya S, associate consultant, department of neurology, Rela Hospital, Chennai notes that biomarker changes can occur nearly 20 years before symptoms appear. She highlights the usefulness of these tests in ruling out Alzheimer’s, pointing to their strong negative predictive value. A negative result can give both doctors and families confidence to pursue alternative explanations and care pathways.

The role of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing also deserves attention. U. Meenakshisundaram, director & senior consultant, neurology, MGM Healthcare, Chennai, notes that Indian labs now offer CSF analysis for beta-amyloid and phosphorylated tau at a cost of around ₹20,000–₹25,000. Although it requires a lumbar puncture and is thus more invasive, many patients and families opt for it if it provides diagnostic clarity. He also mentions that newer, less invasive serum-based tests for Alzheimer’s biomarkers have recently been approved in the United States, though these are not yet available in India.

Post-diagnosis medical care and management

In terms of treatment, there is growing global excitement about novel therapies. Dr. Meenakshisundaram emphasis that two monoclonal antibodies — lecanemab and aducanumab — have been approved in the United States in recent months. These therapies target amyloid plaques and aim to slow disease progression. Though not yet available in India, their approval marks a turning point in how the medical community thinks about Alzheimer’s care.

Aditya Gupta, director, neurosurgery & cyberknife, Artemis Hospital, Gurugram, stresses that we are now in an era where the goal is not just to manage symptoms but to attempt to modify disease progression. He says that early diagnosis paired with these emerging therapies may finally allow patients and caregivers to move from despair to hope.

However, across all experts, there is consensus on several guiding principles. First, dementia is not synonymous with Alzheimer’s disease. Diagnosing someone with Alzheimer’s prematurely, especially without ruling out other causes, risks missing treatable conditions. Second, investigations must be pragmatically chosen. Dr. Prabhakaran insists that tests should only be performed if their results will influence clinical management. There is no merit in subjecting patients to expensive tests that do not offer actionable insights. Third, biomarkers are tools — not solutions. They should only be used when the clinical context supports their necessity. Finally, there is a strong push to empower caregivers with knowledge. Early, accurate diagnosis, even if it confirms an irreversible condition, helps families prepare and cope more effectively with behavioural changes and caregiving needs.

Cautious hope

Experts say that the outlook for dementia care in India is cautiously hopeful. Clinicians are well-informed and increasingly equipped with both traditional tools and cutting-edge diagnostics. Public awareness is growing, particularly among caregivers who seek clarity and early intervention. The next challenge lies in making diagnostics and future therapies more accessible and affordable. With global trials progressing and India’s healthcare ecosystem adapting rapidly, dementia care may soon offer more definitive pathways for diagnosis, management, and even therapeutic intervention.

Dr. Prabhakaran adds, “We are on the cusp of a change. A decade from now, early detection may not just offer clarity — but treatment.” For now, the focus must remain on early clinical evaluation, ruling out reversible causes, and empowering caregivers with the knowledge and resources they need to navigate this complex condition.

Published – June 07, 2025 04:59 pm IST