We have shown in considerable detail in our previous articles published in the previous two issues of Janata Weekly that the Indian economy is in deep crisis. The actual growth rate of the economy is much less than is being projected by the Modi Government. There is massive unemployment in the country; we estimate that more than half the people of working age are unemployed. There is acute distress; probably around 70 percent of the population is mired in poverty. India is facing a hunger emergency. According to the latest report by the FAO (in association with four other UN agencies) on the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity around the world, 22 percent of the country’s population is severely food insecure, and as many as 55.6 percent of the people are unable to afford a healthy diet.[1] Within the framework of welfare capitalism, the most effective solution to these terrible crises is that the government should greatly increase its spending on the people, by making a huge increase in its budget outlay.

An analysis of the components of the GDP also points to the same conclusion.

GDP in any economy equals: Private Final Consumption Expenditure (PFCE, which is a proxy for household consumption) + Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF, which is a measure of total private investment) + Government Final Consumption Expenditure (GFCE, this means government spending on providing services and goods directly for the country).[2] We present these various components of the GDP in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1: GDP and its Components, 2022–23 to 2023–24 (Rs. Crore)[3]

| 2022–23 (FRE) (2) | 2023–24(PE) (1) | Growth rate (1 over 2), % | |

| GDP at Constant Prices (at 2011–12 prices) | 1,60,71,429 | 1,73,81,722 | 8.2 |

| Private Final Consumption Expenditure (PFCE) | 93,23,825 | 96,99,214 (55.8%) | 4 |

| Govt Final Consumption Expenditure (GFCE) | 16,13,726 | 16,53,333 (9.5%) | 2.5 |

| Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) | 53,46,423 | 58,26,880 (33.5%) | 9 |

Figures in brackets = Share in GDP;

PE=Provisional Estimates; FRE= First Revised Estimates

Table 5.1 shows that the 8.2 percent GDP growth rate clocked in 2023–24 is mainly due to a large increase in private investment (that is, GFCF), which has gone up by 9 percent over the previous year. On the other hand, while private consumption (PFCE) is the biggest component of India’s economy, accounting for 56 percent of the GDP in 2023–24, Table 5.2 shows that growth rate of private consumption has consistently fallen during the post-pandemic period from 11.7 percent in 2021–22 to 6.8 percent in 2022–23 and to a lowly 4 percent in 2023–24. But private investment depends upon growth of demand. This only means that the increase in GFCF observed in 2023–24 is not sustainable, unless PFCE picks up in the coming years.

{Actually, growth in PFCE has been slowing down ever since the Modi Government assumed power in 2014 (even if we exclude the pandemic year of 2020–21) — it was an average of 7.5 percent during the triennium FY15 to FY17, and 6.2 percent during the triennium FY18 to FY20.[4] Such a long stretch of consumption slowdown has not been observed in the last two decades.[5]}

Table 5.2: Private Consumption: Percentage Change over Previous Year [6]

| 2020–21 (3rd RE) | 2021–22 (2nd RE) | 2022–23 (1st RE) | 2023–24 (PE) | |

| PFCE: % change over previous year (at constant prices) | –5.3 | 11.7 | 6.8 | 4 |

PE=Provisional Estimates; RE = Revised Estimates

The growth rate of private consumption is the average for both the poor and the rich. Because of the sharp rise in inequality during the Modi years and the huge increase in poverty levels in the country, it is very likely that the small increase in private consumption in 2023–24 only reflects the rising consumption of the rich; the consumption of the poor may even be in decline. Even mainstream political analysts have characterised India’s economic recovery during the post-pandemic period as ‘K-shaped’: meaning led by the upper class, with growth in demand for premium goods outstripping that for the mass-market segment.[7]

The increasing economic distress being faced by the majority of the people during the past decade can also be observed in data put out by the RBI Annual Report of 2024. It shows that net household savings have fallen to a record low of 5.2 percent of the gross national disposable income (GNDI) in 2022–23, from 7.9 percent in 2015–16.[8] A report in the Economic Times in fact points out that net financial savings of households as a percentage of GDP in 2022–23 had fallen to a five-decade low of 5.3 percent.[9] This means that people are drawing down on savings to fund consumption — an indication of falling incomes and rising distress.

Therefore, for the economy to have a sustained recovery, it is important that the government greatly increases its expenditure. So far as the ordinary people are concerned, even if this does take place, they will only benefit from it if the government increases its spending in such a way that it leads to an increase in domestic consumption and puts purchasing power in the hands of the people. That would lead to an increase in domestic demand, and fuel an increase in private investment.

But before we begin our analysis of Budget 2024–25, let us take a look at the state of the Modi Government’s revenues over the past decade, and the scope for increasing them.

Overview of Modi Government’s Revenues: 2014–15 to 2023–24

In Table 5.3, we have given the share collected by the Centre and the share collected by the States in the total government revenues raised by both.

Table 5.3: Share of Centre and States in Total Revenue Collection* [10]

| Direct Tax Revenues | Indirect Tax Revenues | Total Tax Revenues | Non-Tax Revenues | Total Revenues | |

| Centre | 88.3% | 48.1% | 63.2% | 54.9% | 70% |

| States and UTs | 11.7% | 51.9% | 36.8% | 45.1% | 30% |

*The percentages given in the table are the average of percentages for the years: 2014–15 A to 2021–22 A, 2022–23 RE and 2023–24 BE.

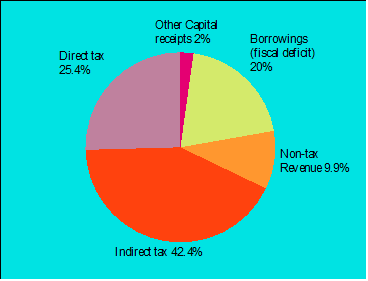

In Chart 5.1, we have given the average breakup of the total revenues of Centre and States during the decade 2014–15 to 2023–24, that is during the first two terms of the Modi Government at the Centre.

Chart 5.1: Composition of Total Revenues of Centre and States, Average: 2014–15 to 2023–24 BE [11]

The data given in the chart are the average of percentages for the years: 2014–15 A to 2021–22 A, 2022–23 RE and 2023–24 BE.

Borrowings includes only the borrowings of the Centre.

The Centre collects 70 percent of the total revenues of the Centre and States [see Table 5.3]. In Chart 5.2, we give the break-up of the total revenues of the Centre.

Chart 5.2: Composition of Total Revenues of Centre, Average: 2014–15 to 2023–24 BE [12]

Data is average for the years 2014–15 A to 2021–22 A, 2022–23 RE and 2023–24 BE.

A critical examination of the data reveals the following.

i) Low Direct Taxes

Tax revenues constitute the biggest part of total government revenues of the Centre and States combined. Over the period 2014–15 to 2023–24 BE, they constituted an average of 68 percent of the total government revenues (Chart 5.1).

Government’s tax revenues have two components, direct taxes and indirect taxes. Direct taxes are levied on incomes, such as wages, profits, property, etc., and so fall directly on the rich; while indirect taxes are imposed on goods and impersonal services, and so fall on all, both rich and poor. An equitable system of taxation taxes individuals and corporations according to their ability to pay, which in practice means that in such a system the government collects its tax revenues more from direct taxes than indirect taxes. The developed countries collect the bulk of their tax revenues from the rich, that is, through direct taxes. The ratio of direct taxes to total tax revenue is 76.6 percent for USA, 67 percent for Japan, 61.8 percent for South Korea, 57.1 percent for Germany, 59.6 percent for UK, 74.5 percent for Australia, and 72.7 percent for Canada.[13] The Economic Survey 2017–18 of the Government of India too mentions that direct taxes account on average for about 70 percent of total taxes in Europe.[14]

In India, the Centre collects the overwhelming share of the total direct tax revenues — 88.3 percent (see Table 5.3).

The Modi Government has been giving huge concessions in direct taxes paid by the rich. First, the Modi Government did away with the wealth tax in 2016; admittedly it was not fetching much revenue even then, but doing away with it was a signal. Then, in 2019 the government reduced the base corporate tax rate for then existing companies from 30 percent to 22 percent, and for new manufacturing firms, incorporated after October 1, 2019, to 15 percent from 25 percent. A press note released by the government stated that the estimated revenue loss due to the corporate tax cut would be Rs. 1.45 crore per year.[15]

Within this lowered tax rate, big companies are able to use loopholes and game the system to pay a lower tax rate as compared to small companies. In the latest year for which data are available, the effective tax rate for large corporations was close to 20 percent, whereas for small firms with the profit range of Rs. 1 crore to Rs. 10 crore, it was 26 percent.[16]

Apart from reduction in tax rates, the Centre has also been giving mind-boggling tax concessions to the corporate houses.

The result of these low tax rates, tax concessions and other transfers to the corporate sector[17] is that the corporate sector is “swimming in excess profits”. This is not a quote from a business newspaper, it is an admission by the Economic Survey 2023–24. It gives data in support of its contention:

“… the corporate sector has never had it so good. Results of a sample of over 33,000 companies show that, in the three years between FY20 and FY23, the profit before taxes of the Indian corporate sector nearly quadrupled. Further, newspaper headlines told us that the corporate profits-to-GDP ratio rose to a 15-year high in FY24.”[18]

The second consequence of this largesse to corporate houses is that the contribution of corporate taxes to the Centre’s gross tax revenues is declining. This can be seen from Chart 5.3. While gross tax revenues of the Centre have increased from 10 percent of GDP in 2014–15 A to 11.4 percent in 2023–24 BE, corporation tax collections have decreased from 3.4 percent to 3.1 percent of GDP.

Chart 5.3: Gross Tax Revenues and Corporation Tax Revenues as % of GDP, 2014–15 to 2023–24

GTR: Gross tax revenues

The third consequence of low corporate taxes is even more bewildering: income taxes are now contributing more to the Centre’s gross tax revenues (GTR) than corporate taxes! In 2014–15 Actuals, the contribution of corporate taxes to the Centre’s GTR was substantially more than that of income taxes — corporate taxes totalled Rs 4.3 lakh crore, while income taxes contributed Rs 2.7 lakh crore. But due to the enormous tax concessions / exemptions given to the corporate sector over the past decade, this has now got reversed. In 2023–24 RE, while corporate tax collections totalled Rs. 9.23 lakh crore, income tax collections were significantly higher at Rs. 10.22 lakh crore. This can also be seen in their relative share in gross tax revenues. While in 2014–15 Actuals, the share of corporate tax collections in GTR of the Centre was 13.2 percentage points more than the share of income tax collections, in 2023–24 RE this ratio had got inverted — income tax collections were now higher by nearly 3 percentage points (see Chart 5.4). This means that the middle classes are now contributing more to Central Government’s tax collections as compared to corporate houses.

Chart 5.4: Trend of Corporate Tax and Income Tax Revenues, 2014–15 to 2023–24

GTR: Gross tax revenues

ii) High Indirect Taxes

To compensate for this revenue loss, the Modi Government has hugely increased indirect taxes:

- it has imposed GST on even essential commodities of daily consumption, like pre-packed and labelled wheat, rice, pulses and other foodgrains, several milk products like curd and paneer, fish and meat, several stationery items like pencil sharpeners and ink, and so on;

- it has hiked excise duty (including cesses) on petrol and diesel — in fact, by 2020, it had increased the excise on petrol by more than 3 times, and that on diesel by 9 times, before reducing it to their present level due to electoral compulsions (see Table 5.4).

Table 5.4: Excise Duty on Petrol and Diesel, 2014 and 2023 (Rs. / litre)[19]

| May 2014 | May 2020 | January 2024 | |

| Excise Duty on Petrol | 9.48 | 32.98 | 19.90 |

| Excise Duty on Diesel | 3.56 | 31.83 | 15.80 |

The total income of the Centre from these two indirect taxes during the past 10 years of Modi rule [2014–15 to 2023–24 (RE)] totals a whopping Rs. 76.99 lakh crore (see Table 5.5).

Table 5.5: Centre’s Revenue from Petrol–Diesel Taxes and GST,

2014–15 to 2023–24 (Rs. lakh crore)[20]

| 2014–15 to 2023–24 | |

| Income from Taxes and Duties on Crude Oil and Petroleum Products | 30.24 |

| 2017–18 to 2023–24 | |

| Income from GST | 46.75 |

| Total | 76.99 |

These two indirect taxes together contributed to more than one-third (35.6 percent) of the total gross tax revenues of the Central Government over these 10 years![21]

The consequence of the direct tax concessions on one hand, and massive hike in indirect taxes on the other, is that in India, for every Rs. 100 collected by the general government (Centre and States combined) as tax revenue, only around Rs. 37 comes from direct taxes, and the rest, ~Rs. 63, from indirect taxes (see Chart 5.6).

Chart 5.6: Direct Taxes as % of Total Tax Revenues (Centre + States), 2014–15 to 2023–24 BE [22]

The burden of paying indirect taxes falls disproportionately on the poor, both individually as well as collectively. At the individual level, a poor person pays a larger portion of his/her income as indirect taxes as compared to the rich. And collectively too, the bulk of the indirect taxes collected by the government come from the poor. A 2023 Oxfam report on growing inequality in India estimates that the bottom 50 percent of the population pays six times more on indirect taxes as a percentage of income compared to the top 10 percent. And of the total GST collected from food and non-food items, 64.3 percent comes from the bottom 50 percent, one-third from middle 40 percent and a meagre 3–4 percent come from the top 10 percent.[23]

It is this huge rise in indirect taxes that is responsible for the steep rise in inflation over the past few years. And it is the poor who are the worst sufferers of rising inflation. So, they are double hit.

iii) Low Government Tax Revenues

Developed capitalist countries not only collect the bulk of their tax revenues from the rich as direct taxes, their total tax collections are also very high. The average tax revenues of the governments of the developed countries (the 38 countries of the OECD) as a percentage of their GDP (this is called tax-to-GDP ratio) was 34 percent in 2022.[24] That is why, in all these countries, while the policies of their governments are oriented towards maximising the profits of big corporations and wealth of the rich, they also collect significant amount of taxes from them and spend it on providing education, healthcare and other welfare services for their people.

The godi media, mainstream economists and corporate honchos are all jubilant about India’s rapidly growing GDP, and are proclaiming that we are going to join the ranks of the developed countries very soon. But they are all silent about the need to increase tax revenues to finance an increase in public investment to tackle India’s appalling unemployment, poverty and hunger crises.

Our GDP may be very large, but the Modi Government is giving so many tax concessions to the rich (we discuss these in a later article) that the total direct tax revenues of the government are very low. The huge increase in indirect taxes has not been enough to compensation for the decline in direct tax revenues.

Consequently, India’s tax-to-GDP ratio (including taxes of both Centre and States) has fluctuated between 16 and 17 percent during the past decade (Chart 5.7).

Chart 5.7: India Tax-to-GDP Ratio, 2014–15 to 2023–24 (in %) [25]

This figure is among the lowest in the world. In 2022, India’s tax-to-GDP ratio was equal to that of Kenya and Burkina Faso; lower than that of El Salvador, Nepal and Chile; significantly lower than that of Türkiye, Bolivia and Nicaragua; and substantially lower than that of Brazil, Uruguay and Namibia.[26] It was less than half of the developed countries.

iii) Low Fiscal Deficit

There is another way in which the FM can increase the budgetary outlay, and that is by increasing government borrowings, or in other words, increasing the fiscal deficit. That fiscal deficit is bad for the economy, and governments should not raise money for increasing welfare expenditures by indulging in deficit financing, is bunkum! This fraudulent theory is a part of the neoliberal ideology being promoted since the 1980s by international capital and its flunkey economists. It had been debunked long ago by John Maynard Keynes, one of the greatest economists of the 20th century. He had argued that in an economy where there is poverty and unemployment, the government can, and in fact should, expand public works and generate employment by borrowing, that is, by enlarging the fiscal deficit; such government expenditure would also stimulate private expenditure through the ‘multiplier’ effect. All developed countries, when faced with recessionary conditions, have implemented Keynesian economic principles and resorted to high levels of public spending and high fiscal deficits — such as during the 2007–09 financial recession and more recently during the pandemic crisis.[27]

The reason why institutions like the World Bank and IMF are pushing developing countries like India to reduce their fiscal deficit is because it creates the conditions for international finance capital to enter and dominate their economies.[28] Most importantly, in the name of reducing the fiscal deficit, the WB–IMF also force these countries to reduce their subsidies to the poor and privatise their welfare services like education and health. With India’s external debt rising, international finance capital and the WB–IMF are in a position to impose conditionalities on the Government of India — and one of these conditions is, reduce the fiscal deficit.[29] And so, FM Nirmala Sitharaman is claiming that a reduction in India’s fiscal deficit would be beneficial for the economy. While presenting the interim budget on 1 February 2024, she stated in her budget speech, “We continue on the path of fiscal consolidation, as announced in my Budget Speech for 2021–22, to reduce fiscal deficit below 4.5 per cent by 2025–26. The fiscal deficit in 2024–25 is estimated to be 5.1 percent of GDP, adhering to that path.”

The average fiscal deficit of the Central Government in the 1980s was around 7 percent of GDP.[30] It is only after the Government of India led by Narasimha Rao with Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister accepted the World Bank imposed Structural Adjustment Programme in 1991 that successive governments at the Centre have been harping on the necessity of reducing the fiscal deficit. Last year, that is, during the financial year 2023–24, the budget deficit was 5.9 percent in the budget estimates. Had the ‘nationalist’ BJP Government resisted international pressure and increased the fiscal deficit to the level of the 1980s (7 percent of GDP), the budget outlay would have increased by Rs. 3.3 lakh crore.[31]

iv) Low General Government Total Revenues

As mentioned above, of the total revenues of all kinds collected by the Centre and the States, including Centre’s borrowings, the Centre collects roughly 70 percent, and the States’ own revenue is 30 percent. Furthermore, while the Centre has great flexibility in raising resources if it wishes to do so, the States have few independent sources of revenue and limited access to emergency borrowings. Therefore, the main responsibility for raising budgetary revenues of the general government (that is, Centre and State governments) lies with the Central government.[32]

In India, the Modi Government has not only been giving huge tax concessions to the big corporate houses, it has also been transferring huge amounts of public funds into the coffers of the rich, through means like loan write-offs, subsidies given in the name of public–private–partnerships, ‘strategic disinvestment’ in public sector corporations, transfer of mineral wealth to private corporations for negligible royalty payments, and so on (we discuss this in detail in a later article). Because of all these concessions and subsidies, not only is the total revenue of the Central government low, the general government revenue (that is, revenue of Centre and States combined) is also low. This is borne out by a comparison with the general government revenues of other countries. India’s total general government revenues as percentage of GDP is among the lowest in the world.

According to the IMF Fiscal Monitor, in 2023, the general government revenue as a percentage of GDP for the 19 Euro area countries was 46.4 percent. For the Middle Income Economies of Europe, it averaged 34.6 percent of GDP, and for Emerging Market Economies of Latin America it was 30.2 percent. But total general revenue of the Government of India (Centre + States combined) was just 20.2 percent of GDP (see Chart 5.8).

Chart 5.8: General Government Revenues as % of GDP: Developed Countries & Emerging Market Economies vs. India, 2023 [33]

So, Can the Government Increase its Revenues?

From the above discussion, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- it should be possible for the Government of India to increase its tax revenues and bring the tax-to-GDP ratio to near that of the Emerging Market Economies (just to remind our readers, the tax-to-GDP ratio of the OECD countries is 34 percent, and that of India’s Emerging Market peers like Brazil, Argentina and South Africa is between 27 and 33 percent[34]). Even if the government increases its tax revenues such that the tax-to-GDP ratio goes up to 25 percent, it would still be less than these comparable developing countries. For this, the total general government tax revenues would need to go up to Rs. 73.84 lakh crore from the estimated revenues of Rs. 54.77 lakh crore in the 2023–24 BE [35] — an increase of Rs. 19.06 lakh crore. The Centre has much greater flexibility in raising resources, so assuming that the entire responsibility of raising this is shouldered by it, that means its gross tax revenues would need to go up from Rs. 33.52 lakh crore in 2023–24 BE to Rs. 52.58 lakh crore, an increase of 57 percent.

- it should also be possible for the Government of India to increase its total revenues by at least 50 percent. If it succeeds in doing so, its revenues would still be only 30 percent of GDP, just about the same as that of its Emerging Market Peers! This would require the general government revenues (Centre + States combined) in 2023–24 BE to go up by 10 percent of GDP, or Rs. 29.53 lakh crore.

These targets may appear to be huge, but as we discuss in a later article of this budget analysis series, considering the massive transfers of public wealth and subsidies the government is giving to corporate houses and the rich, this is very doable.

With this background, let us now discuss the budget outlay in the Union Budget 2024–25.

Budget 2024–25: No Effort Made to Increase Revenues

i) Meagre Increase in Gross Tax Revenues

Despite their being so much scope for increasing tax revenues, the FM has announced no increase in taxes on the rich. Instead, she has reduced corporate tax on foreign corporations to 35 percent from the existing 40 percent! She also announced some concessions for domestic and foreign investors, and minor tax concessions for the middle classes.[36] Therefore, gross tax revenue in the 2024–25 budget has gone up by only 11.7 percent over last year’s revised estimates (Table 5.6).

Table 5.6: Gross Tax Revenue, Fiscal Deficit and Budget Outlay,

2022–23 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

| 2022–23 A | 2023–24 RE (1) | 2024–25 BE(2) | Increase, 2 over 1, % | |

| Gross Tax Revenue | 30,54,192 | 34,37,211 | 38,40,170 | 11.72% |

| Within this: | ||||

| Corporation Tax | 8,25,834 | 9,22,675 | 10,20,000 | 10.55% |

| Income Tax | 8,33,260 | 10,22,325 | 11,87,000 | 16.11% |

| GST | 8,49,133 | 9,56,600 | 10,61,899 | 11.01% |

| Fiscal Deficit | 17,37,755 (6.4%) | 17,34,773 (5.8%) | 16,13,312 (4.9%) | |

| Budget Outlay | 41,93,157 | 44,90,486 | 48,20,512 | 7.35% |

Figures in brackets are percentages of GDP.

Continuing the trend of the past few years, in 2024–25 BE also, income taxes contribute more to gross tax revenues as compared to corporation tax.

Ever since the GST was introduced in 2017–18, the revenue earnings from GST have sharply increased and today exceed the earnings from corporate taxes (Chart 5.9).

Chart 5.9: Trend of Corporate Tax and GST Revenues, 2017–18 to 2024–25

For the ongoing financial year 2024–25, the monthly GST collections have been so robust that they have become embarrassing for the government. For the quarter April–June 2024, GST revenue collections stood at Rs. 5.57 lakh crore, as compared to Rs. 5.05 lakh crore in Q1 last year. And so, from July this year, the finance ministry has discontinued releasing detailed GST collection data on the first day of every month, a practice that had continued uninterrupted for 74 months. No reason has been given for discontinuing the release of monthly GST collection data.[37]

ii) Fiscal Deficit Further Reduced

Continuing with the trend of the past years, the Finance Minister has sought to further reduce the fiscal deficit. She proclaims in her budget speech: “The fiscal consolidation path announced by me in 2021 has served our economy very well, and we aim to reach a deficit below 4.5 per cent next year.” For the year 2024–25, the fiscal deficit is estimated at 4.9 percent of GDP.

She further stated in her budget speech that: “From 2026–27 onwards, our endeavour will be to keep the fiscal deficit each year such that the Central Government debt will be on a declining path as percentage of GDP.”

Interestingly, in a post-budget discussion following this year’s budget, Finance Secretary T.V. Somanathan clarified that this meant that the government was abandoning the target of bringing down the fiscal deficit to 3 percent of GDP, a target which, Somanathan said, “has no scientific basis”.[38] But the government would continue to reduce the debt, which meant that it would continue to reduce the fiscal-deficit-to-GDP ratio, or the current year’s borrowing relative to the GDP, even if not to some irrational 3 per cent target.

As we have pointed out above, it is not just that the fiscal deficit target of 3 percent of GDP has no scientific basis. The theory of fiscal deficit reduction itself “has no scientific basis”.

Budget Outlay Stagnant

With the Finance Minister not making any serious effort to increase government revenues, the budget outlay has increased by just 7.4 percent over last year’s revised estimates (see Table 5.6). In real terms, the increase is marginal.

Overall, over the past 10 years, the total budget outlay has trebled. A better picture of how much the government has increased public investment in the economy is obtained by comparing the budget expenditure to GDP. We present that in Chart 5.10.

As can be seen from the chart, the budget outlay to GDP ratio had peaked during the corona period when it increased to 17.7 percent in 2020–21 Actuals. Since then, it has consistently fallen and has come down to 14.8 percent for this year.

Chart 5.10: Budget Outlay and Budget Outlay as % of GDP [39]

Bowing to Imperialist Dictates

The reason why the Modi Government is keeping budgetary expenditure at such low levels was outlined by FM Nirmala Sitharaman while speaking at a function organised by the Bangalore Chamber of Industry and Commerce some time ago. She said that the government’s perspective towards the Union Budget was that the government should be a facilitator and the private sector should be the key driver of economic growth.[40]

That is precisely what is desired by international finance capital. It wants the Indian government to keep its expenditures low. The Modi Government is bowing to its dictates because of India’s worsening external debt and external accounts situation, as discussed in the previous article of this budget series (published in the previous issue of Janata Weekly). To repeat a point we have made above for emphasis: global financial capital wants the Government of India to keep its budgetary expenditure low because it creates the conditions for private capital, particularly international capital, to take control of the economy and mould it according to its desires. When the government is starved of funds, the paucity of funds becomes an argument for various types of privatisation, such as the privatisation of Government firms, selling shares in public sector firms, promoting ‘public–private partnerships’ on terms very favourable to private investors, hawking off valuable national natural assets such as mines, opening sectors of the economy hitherto closed to private/foreign capital, and the like. All these changes create opportunities for private investors to make financial bonanzas. As we see in a subsequent article, this is precisely what is happening in the country. A staggering amount of mineral wealth has been gifted to the corporate sector on the phony ground that the State did not have the resources to develop it. The Government has been desperately showering gifts on the private sector in an effort to get them to invest in infrastructure. In all of this international finance gets a share of the cream.

For all Modi talk of ‘nationalism’, in reality, the Modi Government is only meekly bowing to imperialist dictates.

Notes

1. Severe food insecurity data is for the triennium 2021–23. See Article 3 for source and calculation of this data. Data for percentage of population unable to afford a healthy diet is for 2022, and is sourced from: The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024, Table A1.6, https://www.fao.org.

2. In this definition, we are ignoring net exports and some other components as they are a relatively minor factor.

3. Latest GDP figures, taken from: Press Note on Provisional Estimates of Annual GDP for 2023–24 and Quarterly Estimates of GDP for Q4 of 2023–24, 31 May 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in.

4. Our calculation. For 2023–24, data taken from ibid. For earlier years, PFCE data taken from: Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24 …, MoSPI, 29 February 2024, https://mospi.gov.in.

5. “A Disconcerting Slowdown: Depressing Consumer Demand Dulls the Shine of India’s Post-Covid Domestic Market”, 12 January 2024, https://www.financialexpress.com.

6. PFCE data is given in GDP tables. Data sourced from latest GDP data, as given in Article 1, endnote 38.

7. See for instance: “Household Consumption Still Weak, But Private Sector Capex Shows Revival”, 31 May 2023, https://www.business-standard.com; “India’s K-Shaped Consumption Pattern Continues Post Pandemic””, 8 May 2024, https://www.fortuneindia.com.

8. Annual Report 2023–24, Reserve Bank of India, May 2024, p. 17, https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in.

9. “Household Savings at Five-Decade Low: A Look at Key Numbers”, 10 May 2024, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

10. Our calculation. Revenues of States include own revenues, and excludes transfers from Centre. For total revenues of Centre + States, we have added: Tax and Non-Tax Revenues of Centre and States + Capital Receipts of Centre (including Borrowings) + Non-Debt Capital Receipts of States (this includes: Recovery of Loans and Advances + Miscellaneous Capital Receipts). We have not included borrowings of States in this calculation. This definition of ‘Total Revenues of States and UTs’ is in accordance with Table II.2, State Finances – A Study of Budgets, p. 5, RBI publication, December 2023. Direct and Indirect tax data of Centre and States taken from: Table 106, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy 2023–24, available online at https://rbi.org.in. Non-tax Revenues of States data taken from: Table 100, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy 2023–24 (data excludes Grants from Centre). Non-tax Revenue of Centre taken from Table 93, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy 2022–23. Capital Receipts of Centre (including Borrowings), taken from: Budget at a Glance, Union Budget documents, various years. To calculate ‘Non-debt Capital Receipts of States’: Data for ‘Recovery of Loans and Advances’ taken from Table 101, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy 2023–24; and data for ‘Miscellaneous Capital Receipts’ taken from State Finances – A Study of Budgets, RBI publication, December 2023.

11. Our calculation. Method for calculating Total Revenues of Centre + States is same as ibid. For calculating Total Revenues, Direct tax, Indirect tax and Non-tax revenues of Centre and States, source of data same as ibid. Borrowings (fiscal deficit) are borrowings of Centre, and data is taken from Table 93, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy 2022–23. Other Capital Receipts include: Other Capital Receipts of Centre (excluding Borrowings) + Non-Debt Capital Receipts of States. Other Capital Receipts of Centre (excluding Borrowings) taken from Budget at a Glance, Union Budget documents, various years. Non–debt Capital Receipts of States — source same as endnote 10.

12. Our calculation. Data sources for all data same as ibid.

13. Rohit Azad and Indranil Chowdhury, “Making a Case for the Old Pension Scheme”, 18 October 2022, https://www.thehindu.com.

14. Economic Survey, 2017–18, Volume 1, p. 57.

15. Corporate Tax Rates Slashed to 22% for Domestic Companies and 15% for New Domestic Manufacturing Companies and Other Fiscal Reliefs, Ministry of Finance, Press Release, 20 September 2019, https://pib.gov.in.

16. “Is India’s Growth Story Benefiting Only Big Capital?”, Prashanth Perumal J. interviews Prof. Himanshu and economist Ritesh Kumar Singh, 27 September 2024, https://www.thehindu.com. Similar but slightly different data is given in: Niti Kiran, “Has India’s Corporation Tax Gamble Paid Off Yet?”, 26 March 2023, https://www.livemint.com.

17. These are discussed in detail in a later Article 16 of this budget series.

18. Economic Survey 2023–24, pp. ix–x.

19. “Excise Duty on Petrol was Rs. 9.48/ltr, Diesel Rs. 3.56 in 2014: Minister”, 1 August 2022, https://www.business-standard.com; “Rajya Sabha Unstarred Question No. 278 to be Answered on 3rd February, 2021: Hike in Cost of Petrol/Diesel”, Rajya Sabha Debates, https://rsdebate.nic.in.

20. GST income: Computed by us from Union Budget documents of various years. Income from Taxes and Duties on Crude Oil and Petroleum Products taken from: “Contribution to Central and State Exchequer”, Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell, https://ppac.gov.in. This figure does not include the dividend income of the Centre from the petroleum sector and ‘Profit Petroleum on exploration of Oil/ Gas’ to the Centre. Both these are also indirect taxes and total Rs. 2.45 lakh crore (for the period 2014–15 to 2023–24).[Source: “Contribution to Central and State Exchequer”, https://ppac.gov.in.] Including this, the total indirect tax income of the Central Government from the petroleum sector increases to Rs. 32.69 lakh crore.

21. Our calculation, based on Union Budget figures of various years. For 2023–24, we have taken the Revised Estimates.

22. Our calculation. Based on data for tax revenues of Centre and States given in: Table 106, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy (2023–24), op. cit. Tax data for States for 2022–23 is RE, and for 2023–24 is BE. For Centre, data for 2022–23 is Actuals, and for 2023–24 is RE from budget documents. The direct and indirect taxes of Centre in the Handbook are the same as calculated from budget documents.

23. “Survival of the Richest: The India Story”, Oxfam Report, 15 January 2023, https://www.oxfamindia.org.

24. Revenue Statistics 2023, 6 December 2023, OECD, https://www.oecd.org.

25. Our calculation. Total tax revenues of Centre and States based on data given in: Table 106, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy (2023–24), op. cit. GDP data is latest data as given in Article 1, endnote 38.

26. C.P. Chandrasekhar, “Budget 2024: An Exercise in Manipulated Accounting and a Poor Attempt at Propaganda”, 4 August 2024, https://frontline.thehindu.com.

27. We have discussed this in greater detail in our booklet: Is the Government Really Poor, Lokayat publication, Pune, 2018, http://lokayat.org.in. See also: Prabhat Patnaik, “The Humbug of Finance”, 5 April 2000, www.macroscan.org; “Keynes, Capitalism, and the Crisis: John Bellamy Foster Interviewed by Brian Ashley”, 20 March 2009, http://www.countercurrents.org.

28. We have discussed this in the context of the WB–IMF imposed Structural Adjustment Programme on the developing countries, including India, in our book, Neeraj Jain, Globalisation or Recolonisation?, Chapter 4, Part B, Lokayat publication, Pune, available online at https://lokayat.org.in. See also: Prabhat Patnaik, “The Humbug of Finance”, ibid.

29. These conditionalities are given in several articles available on the internet. See for instance: Eric Toussaint, “ABC of Debt System”, 6 March 2023, https://www.cadtm.org; “Independent Peoples Tribunal Report”, 9 October 2007, https://www.cadtm.org; These conditionalities are also discussed in several of our publications, such as: Neeraj Jain, Globalisation or Recolonisation?, ibid.

30. Our calculation, based on data for gross fiscal deficit given in the RBI publication, Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, 19 January 2001, Part I: Annual Series, “Table 88: Key Deficit Indicators of the Central Government”, https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in.

31. The projected GDP for 2023–24 as mentioned in the Union Budget documents of that year is Rs. 3,01,75,065 crore.

32. “Resource Sharing between Centre and States and Allocation across States: Some Issues in Balancing Equity and Efficiency”, Draft Report of Study for 15th Finance Commission, Institute Of Economic Growth, Delhi, July 2019, https://fincomindia.nic.in.

33. “Methodological and Statistical Appendix. IMF Fiscal Monitor”, April 2024, https://www.imf.org.

34. Global Revenue Statistics Database, OECD, https://www.oecd.org.

35. Our calculation. We have explained above in endnote to Chart 5.7 how we have calculated the total tax revenues of Centre and States.

36. For more on tax concessions to corporations given in Budget 2024–25, see: “Budget 2024: Modi 3.0 Govt Simplifies Taxes, Fosters Foreign Investments”, 23 July 2024, https://www.business-standard.com.

37. “GST Collection Hits Rs. 1.74 Lakh Crore in June; Finance Ministry Stops Monthly Data Release”,5 July 2024, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com.

38. C.P. Chandrasekhar, “Budget 2024: An Exercise in Manipulated Accounting and a Poor Attempt at Propaganda”, op. cit.

39. GDP data are the latest data, taken from the same source as mentioned in Article 1, endnote 38. Budget outlay figures from Union Budget documents, various years.

40. “To Be World Leader, Private Sector Must Be Key Driver of Growth: Sitharaman”, 21 February 2021, https://www.business-standard.com.

(Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.)