Inaugurating the 32nd International Conference of Agricultural Economists in New Delhi on 3 August 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated that agriculture is at the centre of India’s economic policy. He emphasised that small farmers are the biggest strength of the country’s food security. He also highlighted the initiatives being taken by his government in promoting natural and climate-resilient farming.[1]

We examine these claims made by PM Modi in the context of the first budget of his third term, as well as the ten previous budgets presented by his government since 2014.

Whatever happened to doubling of farmers’ income?

It was in February 2016 at a farmers’ rally in Bareilly (UP) that PM Modi first promised that his government would ensure doubling of farmers’ income in five years, by 2022. Soon after, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley repeated the same promise in his budget speech. After that, doubling of farmers’ income remained a staple item in all budget speeches and speeches of ruling party leaders including the Prime Minister. But when 2022 came, both the PM and the FM became silent about this promise, and instead moved the goalpost a further 25 years away, along with a host of new promises that they promised would be fulfilled during this period that was declared as Amrit Kaal.

The reason why the government has stopped talking of farmers’ income, and instead conjured up a new jumla, becomes obvious from the little data available on how much farmers’ income has increased during the Modi years. The Dalwai Committee set up in 2016 by the Modi Government to recommend a strategy for doubling farmers’ income had estimated farming household income in 2015–16 to be Rs. 8,059 per month. For it to double in five years (in real terms, that is, taking inflation into account), farmers’ monthly income should have reached Rs. 21,146 in nominal terms by 2022. It is estimated that the monthly income of farmers had reached only Rs. 12,445 per month in 2022, 40 percent below the target income![2]

And so, the FM in her Budget Speech of 2024 only says that “farmers are our Annadata”, and “efforts for … boosting farmers’ income will be stepped up”. Full Stop!

Let us take a look at the available data on farmers’ income.

The NSSO conducted a Situation Assessment Survey (SAS) of Agricultural Households in 2002–03, 2012–13 and 2018–19. The survey data shows that the average annual farm income (at current prices) per agricultural household from all sources at the all-India level increased from Rs. 25,380 (Rs. 2,115 monthly) in 2002–03 to Rs. 77,112 (Rs. 6,426 monthly) in 2012–13 and further to Rs. 1,22,616 (Rs. 10,218 monthly) in 2018–19. Converting these figures to constant prices, the income of agricultural households in 2002–03, 2012–13 and 2018–19 works out to Rs. 26,971, Rs. 38,900 and Rs. 45,829 respectively.[3]

The annual income for 2018–19 includes an additional source of income that was not included in the earlier surveys of 2002–03 and 2012–13 — income from leasing out of land. In 2018–19, the average Indian agricultural household earned about Rs. 134 per month, or Rs. 1,608 per year, from leasing of land.[4] Excluding this income from the 2018–19 income of Rs. 1,22,616 to make the figures between the various years comparable, the annual income of the average agricultural household in 2018–19 then becomes Rs. 1,21,008 (Rs. 10,084 monthly). In real terms, this works out to Rs. 45,228.[5]

This means that farm income (from all sources) increased at a CAGR of 3.73 percent during the period 2002–03 to 2012–13, which broadly corresponds to the UPA years. During the period 2012–13 to 2018–19, which broadly corresponds to Modi’s first term, this decreased to 2.54 percent.[6]

Not only has farm income growth slowed down during the Modi years as compared to the UPA years, a study of the various components of farm income reveals that agriculture has been pushed into deep crisis.

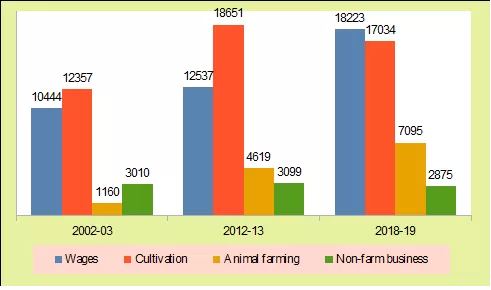

The SAS reports provide data on income for farmer households under four different heads: wages, net receipt from crop cultivation, net receipt from farming of animals, and non-farm business income. The SAS income data, when converted to constant prices, shows that at the all-India level, over the period 2002–03 to 2018–19 (see Chart 9.1):

- annual wage income per farmer household increased from Rs. 10,444 to Rs. 18,223; and

- net income from farming of animals increased from Rs. 1,160 to Rs. 7,095.

Chart 9.1: Annual Income of Agricultural Households by Source

(at constant 2004–05 prices, in Rs.) [7]

The income from both these sources has increased over the two periods 2002–03 to 2012–13, and 2012–13 to 2018–19. However, this has not happened in the case of net receipt from crop cultivation, the most important source of income for farmer households. SAS data shows that:

- net receipt from crop cultivation increased from Rs. 12,357 in 2002–03 to Rs. 18,651 in 2012–13, but reduced to Rs. 17,034 in 2018–19!

The income from crop cultivation in 2018–19 (Rs. 17,034) has fallen to less than income from wages (Rs. 18,223). The Modi Government is pushing our small farmers to become wage labourers!

Even more surprising is that while income from non-farm business marginally increased during the first period (from Rs. 3,010 to Rs. 3,099), it fell sharply during the period 2012–13 to 2018–19 (from Rs. 3,099 to Rs. 2,875) (see Chart 9.1).

We do not have income data for subsequent years. But overall agricultural growth rate data also shows that average agricultural growth during the Modi years is less than that during the UPA years:

- UPA years (2005–06 to 2013–14) — 3.82 percent;

- Modi years (2014–15 to 2023–24) — 3.68 percent.[8]

In all probability, even this low agricultural growth rate during the Modi years is an over-estimate. Harish Damodaran, a renowned journalist and Agriculture Editor of the Indian Express, writes that the government estimates cereal production to have significantly increased to 303.6 mt in 2022–23. On the basis of NSSO’s latest HCES report, it can be estimated that the total annual consumption of cereals by Indian households, in direct or processed-at-home form, was 153.1 mt in 2022–23. Cereal exports totalled 30.7 mt in 2022–23. Cereal grains are also used for manufacture of feed or industrial starch (~ 38 mt), and fermented into alcohol and further distilled into ethanol (50–55 mt). Adding up all this takes the total consumption of cereals to 275–280 mt at best. There is still a difference of around 20 mt. Harish Damodaran asks, “Is the agricultural ministry overestimating production of foodgrains?”[9]

Rising Farmers’ Suicides

The deepening agricultural crisis is pushing our farmers into debt. The SAS of agricultural households carried out by the NSSO in 2019 (mentioned above) found that more than half of India’s agricultural households (50.2 percent) are in debt, with an average outstanding debt of Rs. 74,121. The average debt has gone up considerably since the previous survey in 2013 — by 58 percent. The average annual income of agricultural households was Rs. 1,22,616 in 2019. This means that the average debt was 60 percent of the average income.[10] It also means that a large number of farmers must be much more indebted than this average figure.

The worsening agrarian crisis has pushed the hardy Indian peasants into such despair that they are taking their lives in record numbers. During the first 8 years of Modi rule (from 2014 to 2022), more than 1 lakh farmers and agricultural labourers committed suicide (53,700 farmers and 46,800 agricultural labourers).[11]

Let us now examine the budgetary outlays related to the agricultural sector, to see if the FM has announced some concrete measures to provide relief to India’s farming community from this terrible agricultural crisis.

Jumlas Galore

The Modi Government is a jumla government. Just like the 2015 jumla of doubling farmers’ income in five years, it has come up with a new jumla for agriculture in every subsequent budget speech. To give a few examples:

- In his 2018 budget speech, the then FM Arun Jaitley announced that the government has decided to implement the promise made in the BJP manifesto and has declared Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for crops at 50 percent over production costs. An analysis of the budget papers revealed that the FM had ‘achieved’ this by a sleight of hand: he had lowered the production cost by changing the formula for calculating it![12]

- The corona epidemic hit the country after the presentation of the 2020 budget. During the Covid lockdown later that year, the Modi Government announced a huge relief package for agriculture. The godi media celebrated it as among the most substantial in the world. But most of the relief package turned out to be a mere repackaging of schemes already announced in the 2020–21 BE and previous budgets. A deeper scrutiny of the 2020–21 RE and 2020–21 Actuals reveals that total actual spending of the Ministry of Agriculture and the related Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying in the year 2020–21 was less than the 2020–21 budget estimate! The relief package was only an empty bombast; the Modi Government had actually reduced its spending on agriculture.[13]

- In 2023, the FM announced that the government was going to make India a global hub for millets. Describing millets as “Shree Anna”, she declared: “to make India a global hub for Shree Anna, the Indian Institute of Millet Research, Hyderabad will be supported as the Centre of Excellence for sharing best practices, research and technologies at the international level.” After all the blah-blah, this was the only plan announced. No scheme was announced to provide guaranteed remunerative prices for millets to farmers, which is the most important reason for the decline in acreage under millets.[14]

This year, millets have been forgotten. The new focus is ‘natural farming’ and ‘oilseed production’. In her 2024 budget speech, the FM announced that development of “productivity and resilience in agriculture” is going to be one of the priority areas of the government in pursuit of the goal of viksit Bharat.” For fulfillment of this priority, she announced the following specific actions: i) Promotion of natural farming: “In the next two years, 1 crore farmers across the country will be initiated into natural farming supported by certification and branding.”; and ii) Mission for achieving self-sufficiency in oilseeds: “a strategy is being put in place to achieve atmanirbharta for oil seeds such as mustard, groundnut, sesame, soybean, and sunflower.”

Both these statements are mere rhetoric.

This is not the first time the Finance Minister has announced that priority will be given to natural farming. She had done this in her first speech as Finance Minister in July 2019, and then again in her 2022 budget speech. But the budget allocations for the various schemes meant to promote this have never seen any increase and remained tiny. We discuss this later in this article.

The best way of promoting genuine atmanirbharta in oilseeds is guaranteeing farmers remunerative prices for oilseed production. But that the government is not willing to do, despite massive farmers’ agitations over the issue. Instead, the Modi Government has promoted oilseed imports at the cost of domestic production by lowering import duties on oilseeds. That has led to a surge in import of crude edible oils. During the 12-month period November 2022 to October 2023, India’s imports of edible oils rose by 17.4 percent over the previous corresponding period.[15] Large imports of heavily subsidised edible oils from abroad have resulted in falling farm gate prices for all kinds of oil nuts, dissuading farmers from growing more oilseeds.[16] The government claims that it is reducing import duties to keep edible oil prices in the domestic market low; but that is a lie. The real reason behind keeping oilseed import duties low and promoting oilseed imports is that the Modi Government is seeking to reorient agricultural policies to benefit multinational grain traders, and their Indian collaborators like the Adani and Ambani groups, who are keen to gain control of Indian agriculture. For instance, Adani Wilmar, which is a 50/50 joint venture between Adani Enterprises and Wilmar International, is India’s leading processor of crude palm oil and also the largest importer of edible oils into India.[17] (In September 2024, the Centre suddenly reversed policy and hiked import duty on imported crude palm, soyabean and sunflower oil and on their refined oils, and also permitted the Maharashtra government to procure soyabean from farmers at MSP. The reason for this reversal — Maharashtra assembly elections were due in November, and the State is the country’s second largest soyabean producer.[18])

Let us keep aside Modi’s jumlas, and examine the actual allocations made for agriculture and related ministries in the July 2024 budget.

Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare

For a country like India, where the overwhelming majority of farmers are small and marginal farmers, public investment is critical for agricultural growth, as only the government can invest in improving agricultural infrastructure (such as irrigation) and research (in areas like improving quality of seeds and soil fertility). The Modi Government’s prioritisation of agriculture is best indicated by the total budget outlay for the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare (MA&FW) (see Table 9.1). The outlay for this important ministry is a miniscule 2.75 percent of the total budget outlay. Including the related Ministry of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries (which was earlier a department in MA&FW), the budget allocation increases to 2.9 percent of the total budget outlay — for a sector on which more than half the population depends for its livelihoods (Chart 9.2). This allocation is only marginally higher than last year’s budget allocation (by 5.5 percent), implying a reduction in real terms (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1: Agriculture Budget, 2019–20 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

| 2019–20A | 2022–23 A | 2023–24RE (3) | 2024–25 BE (4) | Increase, 4 over 3, % | |

| Department of Agriculture and Farmer’s Welfare (a) | 94,252 | 99,877 | 1,16,789 | 1,22,529 | 4.9% |

| of which: PM Kisan Samman | 48,714 | 58,254 | 60,000 | 60,000 | |

| Dept of Agricultural Research and Education (b) | 7,523 | 8,400 | 9,877 | 9,941 | 0.6% |

| Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare (a+b = 1) | 1,01,775 | 1,08,277 | 1,26,666 | 1,32,470 | 4.6% |

| Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying (2) | 3,363 | 3,610 | 5,615 | 7,137 | 27.1% |

| Total Agriculture Related Ministries (1+2) | 1,05,138 | 1,11,887 | 1,32,281 | 1,39,607 | 5.5% |

Chart 9.2: Agriculture Budget*, 2019–20 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

* Agriculture Related Ministries = Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare + Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying;

Agri budget = Budget for Agriculture related ministries.

Despite the terrible agricultural crisis, the share of the agriculture and allied sectors in the total budgetary outlay of the Modi Government has fallen by 25 percent during the past five years (from 3.91 percent in 2019–20 A to 2.90 percent in 2024–25 BE). As a percentage of GDP, the allocation is a minuscule 0.43 percent — lower than last year’s 0.45 percent, and 17 percent less than the allocation for 2019–20 A (0.52 percent) (see Chart 9.2).

Bulk of Agriculture Spending on 3 Schemes

Within the declining budgetary outlay for MA&FW, nearly half of the spending is on just one scheme — Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-Kisan). However, it is not an investment for development of agriculture, it is only a relief package meant to provide an allowance to farmers suffering from the agricultural crisis. Even this relief being provided to the farmers is meagre — it translates to a mere Rs. 500 per month. It has not been increased by a single paisa since it was first announced in the 2019 budget. Assuming an average inflation of 6 percent per year, its real value has fallen to just Rs. 345 today. This only means that it is a relief being given out of electoral compulsions; the PM and FM are not genuinely concerned about farmers’ distress. The financial relief it is giving to farmers is much less than the income support to farmers being given in West Bengal and Odisha (which give farmers Rs. 10,000 per year) and Telangana (which gives farmers Rs. 15,000 per acre per year).

Another scheme for which the budgetary outlay is significant is the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY). The scheme aims to provide financial support to farmers suffering crop loss/damage arising out of unforeseen events. The farmer pays the premium at a subsidised rate, the rest is borne by the Centre and the respective State. The budgetary outlay for this scheme is Rs. 14,600 crore this year — which is 12 percent of the total budget of the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare (DA&FW). This scheme is actually a huge scam. The newspapers are full of reports of how insurance companies are not paying farmers compensation in case of crop losses due to vagaries of nature, and thus making huge profits.[19] This is admitted even by the Union Minister of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Narendra Singh Tomar. In a reply given in the Rajya Sabha, he admitted that since the inception of the scheme in 2016–17 to 2022–23, the gross premium collected by the insurance companies totalled Rs. 1,97,657 crore, and the total claims disbursed were Rs. 1,40,038 crore. The insurance companies thus made a profit of Rs. 57,000 crore.[20] The PMFBY dashboard gives a different but similar figure; its data shows that the insurance companies made a profit of Rs. 49,399 crore over the period 2018 to 2022–23 (see Chart 9.3).

For the State of Maharashtra, as per the PMFBY dashboard, the insurance companies collected a gross premium of Rs. 33,946 crore over the period 2018 to 2022–23, and disbursed claims totalling Rs. 22,170 crore, for a total profit of Rs. 11,776 crore (Chart 9.3).

Chart 9.3: India and Maharashtra: Insurance Premium vs Compensation Paid to Farmers, 2018 to 2022–23 (Rs. crore)[21]

A third scheme with a large budget is the Modified Interest Subvention Scheme (MISS). It provides farmers short term loans of up to Rs. 3 lakh for inputs such as fertilisers and seeds, or meeting working capital requirements, at subsidised rates. It has been allocated Rs. 22,600 crore this year. Priority sector lending (PSL) by public sector banks to agriculture (wherein banks are mandated to provide 18 percent of their total lending to agriculture at subsidised rates) has played an important role in the development of agriculture after the nationalisation of banks in 1972. However, since the 1990s, the Centre has been gradually diluting PSL norms, and now loans to corporate farmers and food- & agro-industries are also considered to be priority sector loans. Therefore, in all probability, a significant part of the MISS allocation today goes to benefit agri-business and corporate farmers, rather than small and marginal farmers.[22]

These 3 schemes — PM-Kisan, PMFBY and MISS — consume nearly 80 percent of the budget of DA&FW. All these schemes, especially PM-Kisan and MISS (to the extent it benefits small farmers), are farmer-centric schemes, aimed at providing income support to farmers. While they are important, especially in times of worsening farm crisis, they don’t do anything to tackle the roots of farmers’ distress. The most important strategy for alleviating the crisis gripping India’s agricultural sector is increasing public investment for agricultural development. Earlier, India had several schemes for improvement of the agricultural ecosystem, such as: Integrated Watershed Management Programme, National Afforestation programme (NAP), National Mission for Green India (GIM), Soil Conservation in the Catchment of River Valley Project, National Watershed Development Project for Rain-fed areas, Fodder and Feed Development Scheme as a component of Grassland Development, Command Area Development and Water Management Programme, etc. But the Modi Government is drastically curtailing the allocation for agriculture in the Union Budget, and 80 percent of this limited budget is going towards providing income support and relief to farmers. Therefore, very little money is left for investment in sector-wide support measures necessary for longer-term and sustained improvements in agriculture.

Agricultural Development Neglected

To draw a veil over inadequate funding for various schemes for agricultural development, the FM has subsumed all these schemes under two broad umbrella schemes. The first is the Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY), under which several schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana–Per Drop More Crop, Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana, National Project on Soil and Health Fertility, Rainfed Area Development and Climate Change, Sub-Mission on Agriculture Mechanization including Management of Crop Residue, etc have been merged. From their names itself, it is obvious that these are important schemes for agricultural development. But such is the concern of the Modi Government for holistic development of agriculture that several of these schemes were running only on paper. Thus, in the 2021–22 Budget Actuals, the National Project on Organic Farming had been allocated Rs. 26 lakh, the National Project on Soil Health and Fertility Rs. 8.8 crore, the National Project on Agro-Forestry Rs. 8.4 crore and the National Bamboo Mission Rs. 20 crore. These amounts are not even enough to pay the staff and office expenses of these projects. Since 2023, all these schemes have vanished in the Union Budget papers, as they have been subsumed under the pompous name Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana.

The second umbrella scheme has been given the name Krishionnati Yojana (KY). This clubs together all schemes aimed at strengthening infrastructure of production and marketing of agriculture produce.

After merging around 20 schemes under RKVY and KY in the 2022–23 budget, the FM has drastically cut the budget allocation for these two schemes — as compared to 2022–23 BE, the allocation this year is less by 35 percent in real terms (Table 9.2).[23]

Table 9.2: Budget for Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana and Krishionnati Yojana

(Rs. crore)

| 2022–23 BE | 2022–23 A | 2023–24 BE | 2023–24 RE | 2024–25 BE | |

| Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana | 10,433 | 5,247 | 7,150 | 6,150 | 7,553 |

| Krishionnati Yojana | 7,183 | 4,716 | 7,066 | 6,378 | 7,447 |

| Total budget for Agricultural Development | 17,616 | 9,963 | 14,216 | 12,528 | 15,000 |

Chart 9.4: Budget for Agricultural Development as % of Agriculture Budget

Budget for Agricultural Development = Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) + Krishionnati Yojana (KY); DA&FW = Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare

In Chart 9.4, we plot the Modi Government’s budget allocation for agricultural development (defined as allocation for RKVY and KY) since 2022–23 BE, as a percentage of the total budget for DA&FW. The allocation has declined from a low 14.2 percent in 2022–23 BE to an even lower 12.2 percent this year — an eloquent indicator of the Modi Government’s concern for India’s farm crisis. From the chart, it is apparent that the actual spending for this year too should be much less than the budget estimate.

Reduction in Crop Procurement Budget

Despite all the concerns expressed for the annadata in her budget speech, the FM is silent on the two most important demands of farmers: i) implementation of the Swaminathan Commission recommendation that farmers be given MSP for their produce which is 50 percent over the C2 cost of production (which is the comprehensive cost of production); and ii) the government should evolve a mechanism to ensure that farmers actually get MSP for their crops. While repealing the three farm laws in December 2021 after a year long agitation by the farmers, the Modi Government had promised that it would set up a committee for these demands. Nearly three years later, the government has not initiated any action on this.

Having been forced by the farmers to retreat, the Modi Government is trying to implement the farm laws in a roundabout way. It is gradually winding down all procurement schemes aimed at ensuring that farmers get remunerative prices for their produce. This is evident from budget allocations for various schemes for procurement of farm produce.

The most important scheme that guarantees farmers a decent price for their produce is government procurement for implementing the National Food Security Act (NFSA). In the budget papers, this is called food subsidy. The government buys foodgrains from farmers at MSP, stores a part of it as buffer stock to ensure food security, and organises the distribution of the remaining foodgrains to the people through the countrywide public distribution system. This scheme does not come under the Ministry of Agriculture, but is under the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. The Modi Government has so drastically brought down the food subsidy budget from the peak reached during the pandemic year 2020–21 that spending under this head this year in nominal terms is less than that in 2020–21 Actuals by a huge 62 percent (see Table 9.3)! The reduction in real terms would be around 70 percent![24]

Table 9.3: Budget Allocation for Food Subsidy, 2020–21 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

| 2020–21A | 2021–22A | 2022–23 A | 2023–24 RE | 2024–25 BE | |

| Food Subsidy | 5,41,330 | 2,88,969 | 2,72,802 | 2,12,332 | 2,05,250 |

Two important schemes in the budget of DA&FW meant to assure remunerative prices to farmers for their produce are the Market Intervention Scheme–Price Support Scheme (MIS–PSS) and the Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan (PM-AASHA). PSS-MIS has been in existence for several years, and is meant for procurement of specific agricultural commodities when their prices fall drastically. After spending Rs. 4,007 crore under this scheme in 2022–23 Actuals, the spending on this scheme drastically came down to Rs. 40 crore in last year’s RE. This year, the allocation is zero.

Chart 9.5: Budget Allocation and Actual Spending on PM-AASHA, 2018–19 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

Note: 2018 BE did not have any allocation for this scheme; the scheme was announced in September 2018; so for 2018, the figure is RE. For 2023, the figure is RE, as actual will be known only next year.

The second scheme, PM-AASHA was announced before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections for ensuring that farmers get MSP for pulses and oilseeds. It is supposed to be activated when farm gate prices for these crops drastically fall. But the Centre spent money on this scheme only during the election year 2019, when it spent Rs. 4,721 crore in compensating oilseed farmers. Of this, the government spent 70 percent in the two months preceding the Lok Sabha elections, which began in April 2019. The next year, the Union Budget allocated Rs. 1,500 crore for this scheme, but with the elections over, the government drastically curtailed spending on it to only Rs. 313 crore. For the next three years, the spending on this scheme was zero. Even in the 2023–24 budget estimate, the allocation for this scheme was just Rs. 1 lakh. Then all of a sudden, it dawned on the government that 2024 Lok Sabha elections were near, and it was going to be a tough election fight. And so in the 2023–24 RE, government spending on this scheme zoomed to Rs. 2,200 crore.[25] In the July 2024–25 budget, the FM has further hiked the allocation for this scheme to Rs. 6,438 crore — the highest ever allocation for this scheme (see Chart 9.5). This was clearly done because of the approaching State elections in Haryana and Maharashtra. Soon after the presentation of the budget, on August 4, the Haryana Chief Minister announced that the government would purchase all crops on MSP![26]

Chart 9.6: Budget Allocation for Price Stabilisation Fund, 2018–19 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

The government also procures farm crops under the Price Stabilisation Fund. This scheme is not under the Agriculture Ministry; it is under the Department of Consumer Affairs. This Fund was established to build buffer stocks of important farm commodities like onions, potatoes and pulses, so as to regulate their price volatility. In 2022–23 A and 2023–24 RE, spending on this scheme was down to a token Rs. 1 lakh. Even in the interim budget 2024–25 BE, the allocation remained Rs. 1 lakh. All of a sudden, it has been hiked to Rs. 10,000 crore in 2024–25 BE (see Chart 9.6). The reason is probably the same — the Modi Government’s overconfidence about winning more than 400 seats in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections got badly bruised, it just about scraped through, and so it is desperately seeking to woo farmers in the Assembly elections in Haryana and Maharashtra towards the end of 2024.

Lip Service to Natural Farming

In the long-term, the only solution to the crisis gripping Indian agriculture is promoting organic or sustainable farming techniques in agriculture. In her 2024 budget speech, the FM says that promoting natural farming is going to be one of Modi Government’s priorities as it strives to “take the country on the path of strong development and all-round prosperity.” But this is not the first time the FM is making this claim. She had made the very same claims in her July 2019 budget speech (she then talked of promoting “zero budget farming”), and then again in her 2022 budget speech (this time, she changed her phraseology to promotion of “chemical-free natural farming”). But if we take a look at the fate of the few schemes in the earlier Union Budget documents meant to promote natural / organic / chemical-free farming, it will be obvious that all these pronouncements are mere jumlas. Thus, one of the schemes in the 2021–22 and earlier agriculture budget papers to promote organic farming used to be the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana. Spending on this scheme sharply declined from Rs. 450 crore in 2021–22 BE to a lowly Rs. 89 crore in 2021–22 Actuals. Another scheme used to be National Project on Organic Farming. A footnote to the 2021–22 agriculture budget document states that this project is meant to promote organic farming techniques in the country. The actual spending on this scheme was a princely Rs. 26 lakh that year. The next year (2022), the FM announced in her budget speech that “Chemical-free Natural Farming will be promoted throughout the country”; but both these schemes find no mention in the budget papers — to conceal their tiny allocations, the FM subsumed them under RKVY.

The next year, in the 2023–24 budget, the Modi Government repackaged a sub-scheme of the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana and launched it as a new scheme to promote chemical-free natural farming. It has been given the name National Mission on Natural Farming. The allocation for this scheme was Rs. 459 crore in 2023–24 BE; the revised estimates show that spending has been drastically cut to Rs. 100 crore; we will know the actual spending on this scheme next year.

Budget Allocation for Agricultural Research

Public investment in agricultural research plays a key role in promoting agricultural growth. Unfortunately, the budget allocation for the Department of Agricultural Research and Education has fallen from a low 0.29 percent of the budget outlay in 2014–15 A to an even lower 0.20–0.22 percent during the last 3 years (2022–23 A to 2024–25 BE). India’s public spending on agricultural research and development is less than one-fifth of China.[27] While PM Modi loves talking about Atmanirbhar Bharat, his government is destroying indigenous agricultural development by reducing our already low investment on agricultural research and allowing foreign giant agri-business corporations to enter and dominate this sector. In 2023, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Bayer, one of the world’s largest agribusiness companies, to “develop resource-efficient, climate-resilient solutions for crops, varieties, crop protection, weed and mechanisation.”[28] Before this, ICAR and Bayer had signed research collaboration agreements on cultivation of pomegranates and “Development of Drone based Potatoes Crop Management Technologies”.[29] Clearly, these are attempts to allow corporate tentacles to penetrate and eventually dominate our agricultural economy, by manipulating ICAR’s accumulated public credibility, network and resources. The collaboration with Bayer is particularly dangerous, as it is notorious for promoting toxic chemicals that can cause cancer and other diseases, and is facing several litigations in the US courts. A statement by the Peoples’ Commission on Public Sector and Services, that includes eminent academics, jurists, erstwhile administrators, trade unionists and social activists, has expressed deep concern and anguish over ICAR’s research collaboration with Bayer:

We feel distressed that the Council, which is an apex public sector institution of eminence, the largest of its kind in the world, with its vast network of research associates and field-level extension agencies spread across the length and breadth of the country, which has been coordinating, guiding and managing research and education in agriculture including horticulture, fisheries and animal sciences in India for more than nine decades, an institution which spearheaded the Green Revolution that transformed India’s agriculture and made the country self-sufficient in food grains production, should choose it appropriate to enter into an agreement with a profit-driven MNC and allow it to exploit the Council’s unique brand value, its public credibility and its vast infrastructure to pursue its own commercial plans in the country. In the field of agriculture, ICAR has much more to offer to others than what a private company like Bayer can give…. In our view, such MOUs make a mockery of the so-called “Atmanirbhar” effort of the government, in so far as agriculture is concerned.[30]

Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying

Two important sectors that can help provide some relief to farmers from the agrarian crisis are livestock (this includes the sub-sectors dairy, poultry and meat) and fisheries. The livestock sector provides crucial additional income to a large section of small and marginal farmers. According to NSSO survey data for 2018–19 (see Chart 9.1 above), farming of animals contributed 16 percent of the total income of agricultural households. While income from cultivation declined during the period 2012–13 to 2018–19, real income from animal farming increased at a CAGR of 7.4 percent.[31] And this increase is despite widespread ‘cow vigilantism’, inter-state ban on transportation of animals, and stricter slaughter laws — all of which have adversely affected incomes of farmers from animal farming.[32]

The fisheries sector (fishing, aquaculture and allied activities) is estimated to provide livelihood to more than 1.6 crore people.[33] The budget allocation for the Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying has been increased by 27 percent this year; but this comes on such a low base that the budget outlay for this ministry as a percentage of the total budget outlay is only a tiny 0.15 percent.

Ministry of Rural Development

Conditions in agriculture are intimately tied to the general state of the rural economy, and that is why public spending on rural development is important for the overall development of agriculture.

The Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD) implements several important schemes for rural development, such as Pradhan Mantri Avas Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, and the National Rural Livelihood Mission. It also runs the crucial scheme for rural employment, MGNREGS, and the National Social Assistance Programme that provides pensions and other social assistance to the poor.

Despite being such an important ministry that oversees so many important programmes, the budget outlay for this ministry is hugely disappointing. Total allocation for MoRD is slated to increase by only 4.2 percent this year over last year’s revised estimate — which means a reduction in real terms (Table 9.4)! The budgetary outlay for this year is in fact less than that for 2020–21 A even in nominal terms.

Table 9.4: Budget Allocations for Ministry of Rural Development,

2019–20 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

| 2019–20 A | 2020–21 A | 2021–22 A | 2022–23 A | 2023–24 RE | 2024–25BE | |

| Ministry of Rural Development | 1,23,622 | 1,97,593 | 1,61,643 | 1,77,839 | 1,72,967 | 1,80,233 |

The drastic cut made in the budget for MoRD is better reflected in the allocation for this ministry as a share of the total budget outlay (Chart 9.7) — it has fallen by one-third over this four-year period (from 5.6 percent to 3.7 percent). It is in fact less than the share in the 2014–15 budget too (4.2 percent).

Chart 9.7: Budget Allocation for Ministry of Rural Development, 2014–15 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

Within this ministry, the only scheme whose budget has seen a significant hike as compared to last year’s revised estimate is the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana Rural (PMAY-G) — though its allocation is the same as last year’s budget estimate, Rs. 54,500 crore. The scheme had a target of constructing 3 crore ‘pucca’ houses by 31 December 2024. [It also has an urban counterpart, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana Urban (PMAY-U) that comes under the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs.] While the PMAY-G dashboard claims that more than 2.6 crore houses have been built under this scheme so far [34], the subsidy being provided for building houses under this scheme is so tiny (Rs. 1.20 lakh is given in plain areas and Rs. 1.30 lakh in hilly areas per house) that in all likelihood most of these houses have been built only in government files. Several newsreports available on the internet also say that the scheme is actually one big scam.[35] But ‘the show must go on’. While presenting the 2024–25 budget in Parliament, the Finance Minister stated that the government has decided to construct another 3 crore houses in rural and urban areas, and has made the necessary allocations for this.

Chart 9.8: Budget Allocation for Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, 2020–21 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

Another important scheme under the MoRD is the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) which seeks to build all-weather roads to connect all the 1.6 lakh eligible unconnected habitations in the rural areas in the country. Soon after coming to power, the Modi Government set a target date of 2019 for completion of rural connectivity. In 2022, the MoRD in a press release claimed that “99% of the targeted habitations have been provided all weather road connectivity as on 10.3.2021.”[36] Two years have passed since this claim was made; the scheme should have achieved its target by now. In 2022–23 A, a huge Rs. 18,783 crore was spent on this scheme; and the 2023–24 RE show a spending of Rs. 17,000 crore — even more than the amount spent in 2021–22 A (Rs. 13,992 crore). This year’s budget allocates another Rs. 12,000 crore for this scheme (Chart 9.8). Clearly, this scheme is another big scam; many of these roads are being built only on paper, and shown as washed away during the monsoons. An article in The Wire says: Researchers at Princeton University and the Paris School of Economics have found that almost 500 all-weather roads listed as completed and fully paid for under the PM Gram Sadak Yojana were never built. A Parliamentary Standing Committee that examined this scheme in 2023 has also castigated the government for building poor quality roads under this scheme.[37]

The reason why none of these scams are hitting the headlines is because they are not being investigated. Under the Modi Government, the independence of all investigating agencies has been compromised; even the CAG, supposed to be the supreme audit institution of India that is expected to promote financial accountability and transparency in the affairs of the audited entities, has stopped functioning effectively — its reports have seen a sharp decline under Modi rule.[38]

Let us now take a look at the most important scheme under this ministry, the MGNREGS.

MGNREGS

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) — also called MGNREGA or NREGA (the ‘A’ standing for the Act passed to codify the programme) — is one of the most important social sector expenditures of the Central Government. It is a demand based scheme that guarantees a minimum of 100 days of employment in a year to every willing household. Significantly, it guarantees time bound employment, within 15 days of making such a requisition, failing which it promises an unemployment allowance.

Despite its many limitations such as the provision of providing employment for only 100 days a year and wages below the minimum wage in several States, its benefits far outweigh its faults. In a situation where unemployment and poverty have reached their worst level in several decades, this scheme has been a lifeline for the rural poor. It has the potential to lessen the crisis gripping the rural areas and improve food security. Numerous studies have shown that MGNREGS has had several positive effects, including increasing rural wages, enabling better access to food and thereby reducing hunger, and reducing distress migration from rural areas.[39] On top of it, MGNREGS also leads to the creation of tangible public assets like roads, canals and public wells, among others, which too benefit the countryside.

Notwithstanding these numerous benefits, since it is a UPA scheme, the Modi Government has sought to undermine it ever since it came to power in 2014, by depriving it of the necessary funds. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has in fact called MGNREGS a living monument to the opposition’s failures.[40] The inadequacy of the budgetary allocation made for MGNREGS during the Modi years is obvious from the following facts:

- During the Modi years, the scheme has been able to provide just around 50 days of work to each household in a year (see Chart 9.10) — when the MGNREGS Act guarantees 100 days of work to each willing household.

- All those not given 100 days of work are not being given any unemployment allowance, which is also a guarantee under the scheme.

The only year in which budget allocation for MGNREGS saw a significant increase was the pandemic year 2020–21. The economy collapsed, unemployment skyrocketed, and people migrated back to the villages in crores. The Modi Government was forced to hike its budget allocation for MGNREGS from the budgeted Rs. 61,500 crore (2020–21 BE) to Rs. 1,11,170 crore in 2020–21 Actuals (Chart 9.9). The number of people who took work under this scheme shot up to a record 11.2 crore (Chart 9.10).

Chart 9.9: Allocation for MGNREGS, 2014–15 to 2024–25 (Rs. crore)

Chart 9.10: Employment Provided Under MGNREGS, 2014–15 to 2023–24 [41]

Since then, the Modi Government has been claiming that the economy has undergone a remarkable recovery, and our growth rates are among the highest in the world. But as we have discussed in a previous article of this budget analysis series, this recovery has bypassed the non-agricultural unorganised sector, which provides employment to nearly half the population. Consequently, the demand for work under MGNREGS has continued to be high. In fact, the total number of people who worked under this scheme in all the post-pandemic years has been higher than the pre-pandemic year 2019–20 (see Chart 9.10).

Despite the high work demand under this scheme, a callous Modi Government has reduced the budget allocation for this scheme every year since 2020–21 (Chart 9.9). As compared to 2020–21 A, the allocation this year is 22.6 percent less in nominal terms. In real terms, it is around 39 percent less.[42] The allocation for MGNREGS in this year’s budget is at the same level as last year’s revised estimate, implying a reduction in real terms. The spending on this scheme has declined so steeply that as a percentage of budget outlay, the allocation this year is the lowest in the past 10 Modi years (see Chart 9.9).

Because of inadequate funding, not only has the scheme not been able to provide the mandated 100 days of employment to each willing household (in a year), every year more than one crore people seeking work under this scheme are denied work (Table 9.5). This is again in flagrant contravention of the MGNREGA act, which says that government must provide the necessary funds to provide work to all households seeking work.

Table 9.5: MGNREGS: Number of People Denied Work, 2018–19 to 2022–23 (in crore) [43]

| 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | |

| Total Number of People Denied Work | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.49 |

Last year (2023), a Parliamentary Standing Committee that examined the MGNREGS expressed surprise at the reduction in budgetary allocation for the scheme in 2023–24. It noted that the pruning of funds at budget estimate stage has a “cascading effect on various important aspects such as timely release of wages, release of material share etc. which have a telling impact on the progress of the scheme.” The committee not only asked the Centre to increase its annual budget allocation for the scheme, it also asked the government to extend the employment guarantee provided under the scheme to 150 days.[44]

Instead of increasing budgetary allocations for this scheme, the Modi Government has now come up with a fiendish plan that will discourage people from applying for MGNREGS work, thereby providing justification for the Modi Government to further cut its budgetary spending on this scheme. Since February 2023, it has made wage payments to all those seeking work under MGNREGS conditional on timely uploading of workers’ photographs twice a day, using the National Mobile Monitoring System app. This is causing havoc, as large parts of rural India have poor connectivity. On any day, if the worksite supervisor is not able to timely upload their photographs, workers are denied wages for that day. The budget cut and the National Mobile Monitoring System app are thus made for each other.[45]

The Modi Government has also brought in the Aadhaar-based Payment System (ABPS), under which the worker’s Aadhaar card must be seeded with their job card (which means that all their details in their job card must match their Aadhaar card details). The worker’s wages are then directly credited to a bank account that is linked to their Aadhaar card. The MoRD first mounted pressure on the States to make all wage payments through this system — which led to many workers being denied wages after having worked or workers not being given work because they were not ABPS-enabled. There are also reports that States have deleted job cards of workers who were not eligible for Aadhaar-based payments — according to LibTech India, a consortium of academics and activists, 7.6 crore workers have been deleted from the system over the last 21 months. Now, from January 2024, the Modi Government has made it mandatory that all wage payments under the MGNREGS must be made through the ABPS. As per the government’s own data, as on 11 January 2024, out of a total of 25.6 crore registered workers, only 16.9 crore workers are eligible for ABPS![46]

The evidence is incontrovertible. To compensate for low government revenues because of low direct tax revenues and huge transfer of public funds to the coffers of Modi’s friends, the Ambanis–Adanis,[47] the Modi Government is seeking to strangulate the most important employment guarantee scheme in the country for the rural poor, the MGNREGS.

What should be the budgetary allocation for MGNREGS, to provide 100 days of work to all desirous households? According to Peoples’ Action for Employment Guarantee (PAEG), a MGNREGS research and advocacy group, the scheme needs an allocation of at least Rs. 2.72 lakh crore to guarantee 100 days of work to each willing household. It made this estimate in January last year, in a 2023–24 pre-budget analysis.[48] The government has provided less than one-third of this amount.

Fertiliser Subsidy

Just like it has sought to reduce its food subsidy bill, the Modi Government has been seeking to reduce its fertiliser subsidy bill too ever since it came to power in 2014. But the Ukraine war led to a huge jump in prices of imported fertilisers, forcing it to increase fertiliser subsidy in 2022–23. Over the next two years, its spending on this head has come down again.

Chart 9.11: Fertiliser Subsidy in Modi Budgets, 2014–15 to 2024–25 (Rs. ’000 crore)

In this year’s budget, the FM has reduced fertiliser subsidy by 13 percent as compared to last year’s RE, and by 35 percent as compared to 2022–23 A (both figures in nominal terms). In real terms the decline would be still more. The fertiliser subsidy as a percentage of budget outlay has declined by a huge 43 percent over the past 2 years (see Chart 9.11).

The sharp reduction in fertiliser subsidies has led to an increase in fertiliser prices, further reducing the farmers’ meagre earnings and worsening the crisis gripping Indian agriculture.

The Modi Government is a victim of its own policies. Fertiliser prices in the country are high because the Modi Government has deliberately sought to undermine and privatise the public sector fertiliser industry, in order to promote the private sector fertiliser industry. But the private sector has been more interested in earning high profits from fertiliser shortages rather than increasing production capacity. This has made India one of world’s largest importers of fertilisers and fertiliser materials; and the prices of these imports have zoomed due to the Ukraine war.[49]

There is a very cost-effective and environment-friendly way in which the government can reduce its fertiliser subsidy: by pushing farmers to shift from chemical intensive farming to farming practices that minimise the use of toxic inputs, by using on-farm renewable resources and privileging natural solutions to manage pests and disease. This is known as agroecological agriculture, or more simply, sustainable agriculture.[50] Lakhs of farmers have taken to natural or sustainable farming in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, with exciting results.[51] But as we have seen above, the Modi Government’s claims about promoting sustainable farming are but another jumla.

Why is the Modi Government Strangulating Agriculture?

The real intent behind the Modi Government’s agricultural policies is revealed in a document of Niti Aayog, which was released soon after the Modi Government came to power in 2014. It stated:

“With the corporate sector keen on investing in agribusiness to harness the emerging opportunities in domestic and global markets, time is opportune for reforms that would provide healthy business environment for this sector. Small scale has been a major constraint on the growth of this industry.”[52]

This report of the government’s think tank clearly elucidates the ruling regime’s agenda for agriculture — it is seeking to replace small scale farming by corporate agriculture. This can only be done if small farming is pushed into severe crisis and agriculture becomes so unprofitable that small farmers are forced to sell out their lands to corporate houses and move to urban slums in cities, or become labourers on corporate farms.

This was the real intention behind the three farm laws. We have explained in detail, in two articles published some time ago in Janata Weekly, that the farm laws had been enacted by the Modi Government under pressure from the World Bank and the giant agribusiness corporations of the West, as these foreign corporations want to enter and seize control of Indian agriculture.[53] India’s big corporate houses too are seeking to enter the agriculture sector in a big way. Previously unpublished documents accessed by a group of investigative journalists, The Reporters’ Collective, reveal that the Adani Group had lobbied with the Niti Aayog in 2018 for repealing the Essential Commodities Act that limits companies from hoarding agricultural produce, claiming that it was proving to be a deterrent for industries / entrepreneurs — this was one of the farm laws enacted by the Modi Government two years later.[54]

In April 2020 (at the height of the Covid lockdown!), PM Modi himself launched the SVAMITVA project (Survey of Villages and Mapping with Improvised Technology in Village Areas). The Niti Aayog also released a model Land Titling Act in November 2020, and is mounting pressure on State governments to adopt it. The real purpose behind both is to facilitate the takeover of agricultural lands by corporate houses.[55]

The Modi Government is undoubtedly the most anti-farmer government to have come to power at the Centre since independence.

Appendix: Is Guaranteeing MSP for Farm Produce Affordable?

An important demand of the farmers’ movement is that the Centre bring in a law to guarantee MSP to farmers for their crops.

MSP has been in existence in India for more than five decades. Every year the government announces MSP for 23 crops before the sowing season. They include 7 cereals (paddy, wheat, maize, bajra, jowar, ragi and barley), 5 pulses (chana, tur/arhar, moong, urad and masur), 7 oilseeds (rapeseed-mustard, groundnut, soyabean, sunflower, sesamum, safflower and nigerseed) and 4 commercial crops (sugarcane, cotton, copra and raw jute). Why, then, are farmers asking for a legal guarantee? Because the MSP announcement is only on paper; except for a few crops, there is no intervention by the government to ensure that farmers get this minimum price for their produce. The government intervenes only for rice, wheat, cotton, and occasionally for pulses and other crops; it has also made it mandatory for sugar mills to pay the farmers ‘fair and remunerative price’ (which is fixed by the government) for sugarcane procured from them. Farmers are demanding that the government intervene for the remaining crops too, and insulate the farmers from price volatility and ensure that they get at least the MSP for their crops.

The main reason why successive governments have dithered on legalising this mechanism is because of the fear of excessive fiscal costs of such a guarantee. Analysts have claimed that it would cost anywhere between Rs. 10–18 lakh crore and bankrupt the government. There was similar fear mongering when the UPA government was in the process of enacting the National Food Security Act (NFSA) and the MGNREGA. Not only did these acts not bankrupt the government; on the contrary, they proved to be a lifeline for people during the pandemic.

Let us make a realistic estimate of how much such a legal guarantee would cost the government. The belief that a guarantee to implement MSP means that the government will have to procure all the agricultural produce is a fallacy. That is because farmers consume a part of their produce, and so only a fraction of the produce comes to the market for sale. This is known as marketable surplus. As mentioned above, the government already procures a significant amount of this surplus for some crops at MSP; for sugarcane too, farmers receive the MSP from sugar mills as the government has made it mandatory. For the remaining of the 23 crops for which MSP is notified, agriculture-affairs journalist Harish Damodaran estimates that providing a legally guaranteed MSP would cost the government at the most an additional Rs. 5 lakh crore.[56] Damodaran further explains that actual spending needed would be much less than this, for two reasons. Firstly, the government does not need to buy all the marketed surplus. Just buying a fourth of it will ensure that the market price will be lifted above the MSP level in case of most crops. And secondly, except for the crops which the government subsidises and distributes to the people through the PDS, the remaining crops are going to be sold by the government in the market and therefore it would get much of its expenditure back. This means that actual spending by the government to give a legal guarantee to MSP for all the 23 notified crops would probably be not more than Rs. 2.5 lakh crore (in addition to what it is already spending on crop procurement from farmers).

Another article by T.N. Prakash Kammardi, “It is Possible to Ensure Farmers’ Right to Remunerative Prices Through a Legal Recourse”, also makes a similar estimate. The author, an eminent agricultural economist of Karnataka, estimates that for the principal farm commodities of the entire country, ensuring that farmers receive remunerative prices for their produce would require a price stabilisation fund of around Rs. 2.3 lakh crore.[57]

A third estimate has been made by noted academicians Amit Bhaduri & Kaustav Banerjee. In their article “An MSP Scheme to Transform Indian Agriculture”, they estimate that guaranteeing MSP for farm produce would cost around Rs. 5 lakh crore.[58]

This expenditure of between Rs. 3 to 5 lakh crore will directly benefit around 50 percent of our population, and an additional 20–30 percent population employed in the unorganised sector. It will in turn generate massive positive economic externalities across the entire economy, and greatly boost demand which will greatly boost our industrial production. And this expenditure is entirely affordable — it is of the same order of magnitude as DA to public sector employees (less than 5 percent of the population). And it is much less than the tax breaks and loan waivers being given to big corporate houses, who provide employment to less than 2 percent of the population (we discuss this in a later article of this budget analysis series).

Notes

1. “Agriculture Is at the Centre of Economic Policymaking, Says PM Modi at Global Agri Economists Meet”, 4 August 2024, https://indianexpress.com.

2. Kirankumar Vissa, “A Grim Future: What Happened to the Promise of Doubling Farmers’ Income by 2022?” 5 February 2022, https://thewire.in.

3. A. Narayanamoorthy and K.S. Sujitha, “Trends and Determinants of Farmer Households’ Income in India: A Comprehensive Analysis of SAS Data”, Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, Volume 76, Number 4, October–December 2021, https://isaeindia.org. Other papers available online give similar data. For instance, see: “Why Doubling Farmers’ Income Is Still a Dream”, 15 May 2022, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com.

4. For income from leasing out of land, see: Shweta Saini and Siraj Hussain, “Most Indian Farmers Faced Erosion of Their Real Incomes Since 2012–13 But Survey Can’t Tell”, 13 October 2021, https://theprint.in.

5. Our calculation: 122616 / 45829 = 2.6755; 1608 / 2.6755 = 601; 45829 – 601 = 45228.

6. Our calculation.

7. A. Narayanamoorthy and K.S. Sujitha, “Trends and Determinants of Farmer Households’ Income in India: A Comprehensive Analysis of SAS Data”, op. cit.

8. Our calculation. Data for agricultural GDP growth during the years 2004–05 to 2011–12 taken from: Press Note on National Accounts Statistics Back-Series (2004–05 to 2011–12), 28 November 2018, http://www.mospi.gov.in; data for agricultural GDP growth during the years 2012–13 to 2022–23 taken from: Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24 …, MoSPI, 29 February 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in. Data for 2023–24 is taken from: Press Note on Provisional Estimates of Annual GDP for 2023–24 and …, 31 May 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in. Data for 2020–21 is: Third Revised and Final Estimate; 2021–22 is: Second Revised and Final Estimate; 2022–23 is: First Revised Estimate; and 2023–24 is: Provisional Estimate.

9. Harish Damodaran, “How Demand for Cereals in India Is Changing”, 23 June 2024, https://indianexpress.com.

10. “Income and Debt Account of India’s Farmers – Explained”, 20 November 2021, https://www.indiatoday.in.

11. Calculated by us from: Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India, NCRB, annual reports from 2015 to 2023, https://ncrb.gov.in.

12. Tushar Dhara, “Budget 2018: By Hiking Minimum Support Price, Modi Govt Makes Good 2014 Promise, But All Is Not as it Seems”, 2 February 2018, https://www.firstpost.com.

13. Neeraj Jain, “Budget 2021–22: What Is in it for the People? – Part 2”, 7 March 2021, https://janataweekly.org.

14. “International Year of Millets – Achievements and Shortcomings”, ForumIAS, 22 May 2024, https://forumias.com; Chandra S. Nuthalapati et al., “Indian Millet Cultivation Plagued by Low Yields, Prices, and Profits”, 3 May 2024, https://tci.cornell.edu.

15. 2022–23 (Nov.–Oct.) Import of Veg. Oils – 167.1 Lakh Tons, 13 November 2023, https://seaofindia.com.

16. “Decision to Freeze Import Duty on Edible Oil Will Impact Goal of Achieving ‘Aatma Nirbharta’: Solvent Extractors”, 23 January 2024, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com; “Import Duty Cuts on Essentials Harms Farmers: Unions”, 22 August 2023, https://www.thehindu.com; “Why Farmers Are Not Enthusiastic About FM Sitharaman’s Call for Atmanirbharta in Oilseeds”, 5 February 2024, https://indianexpress.com.

17. For more on this, see: “When Multinational Grain Traders Told an Official Committee Why They Wanted the FCI to Be Wound Up”, RUPE, Mumbai, 24 January 2021, https://janataweekly.org.

18. Harish Damodaran, “Explained: Centre’s Pro-Farmer Turn in Edible Oils”, 24 September 2024, https://indianexpress.com.

19. See for instance: “State Looks to Centre as Crop Insurance Firms Deny Advance to Farmers”, 20 October 2023, https://indianexpress.com; and: “How Crop Insurance Is Used as Political Tool to Leverage Farmers’ Support in Marathwada”, 26 March 2024, https://indianexpress.com.

20. Premium Collection and Insurance Claims under Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, 21 July 2023, https://www.pib.gov.in.

21. Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, Administrative Dashboard, https://pmfby.gov.in. Data accessed on 8 October 2024. The dashboard gives data from 2018. For 2018, we have taken data for both Rabi and Kharif crops. For 2022–23, we have taken data only for Kharif crop of 2022 and Rabi crop of 2023, and excluded data for Kharif crop of 2023.

22. See: Priya Dharshini, “Farm Acts and Misplaced Priorities of Priority Sector Lending”, Centre for Financial Accountability, Delhi, October 2020, https://www.cenfa.org.

23. Our calculation, assuming average annual inflation of 6 percent.

24. Our calculation, assuming average annual inflation of 6 percent.

25. Shreegireesh Jalihal & Navya Asopa, “Modi’s Scheme to Double Farmers’ Income Goes on Overdrive During Elections, Stalls Otherwise”, 7 May 2024, https://www.reporters-collective.in.

26. “Haryana Govt to Purchase All Crops on MSP: CM Saini”, 5 August 2024, https://www.hindustantimes.com.

27. Alejandro Plastina and Terry Townsend, “World Spending on Agricultural Research and Development”, The ICAC Recorder, March 2023, https://icac.org.

28. “ICAR and Bayer Signed a MoU”, 1 September 2023, https://icar.org.in.

29. “ICAR–CPRI Trials Drone-Based Potato Crop Management”, 10 February 2021, https://www.bayer.in; “AIKS Demands Union Government to Immediately Withdraw MOUs Signed by ICAR with Corporate Giants Resist Corporatisation of Agriculture”, 1 November 2023, https://kisansabha.org.

30. “Review ICAR–Bayer MOU: PCPSPS”, 14 October 2023, https://indianpsu.com.

31. Our calculation, based on data in Chart 9.1.

32. See for instance this report: Prachi Salve, “Cow Protection Ideologues Are Destroying Livelihoods”, 10 March 2020, https://www.indiaspend.com.

33. Annual Report 2022–23, Department of Fisheries, Government of India, https://dof.gov.in.

34. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana – Gramin, Dashboard, https://dashboard.rural.nic.in, accessed on 10 July 2024.

35. “Money to Ineligible Beneficiaries, SC/STs Lower in Priority: CAG Flags Faults in Rollout of PM Awas Yojana in Madhya Pradesh”, 23 February 2024, https://indianexpress.com; “PM Awas Yojana-Subsidy Scam”, 16 February 2024, https://tehelka.com; Bhaswati Sengupta & Vikas Mavi, “Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana: Allegations of Corruption, Discrimination, Political Bickering Mar the Scheme”, 16 February 2023, https://theprobe.in; “CAG Pulls Up Govt Over Graft in Implementation of PMAY”, 21 September 2022, https://www.hindustantimes.com (this report is for PMAY-Urban, but it is indicative of the extent of data fudging taking place under this scheme).

36. Implementation of Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, 15 March 2022, https://rural.gov.in.

37. Risha Chitlangia, “Parliamentary Panel Flags Poor Quality of Rural Roads, Slow Pace of Work Under PM Gram Sadak Yojana”, 27 July 2023, https://theprint.in. P. Raman, “Crumbling Infrastructure: A Gift of the Gujarat Model of Neta-Babu-Business Nexus”, 23 July 2024, https://thewire.in.

38. Aakar Patel, “Transparency in Modi Era? CAG’s Working Shows It Remains Opaque”, 17 October 2023, https://thewire.in.

39. See for instance: Sudha Narayanan, “The Continuing Relevance of MGNREGA”, 17 March 2020, https://www.theindiaforum.in; Stefan Klonner and Christian Oldiges, “The Welfare Effects of India’s Rural Employment Guarantee”, Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford, UK, October 2019, https://www.ophi.org.uk.

40. “Modi Says MNREGA Will Continue as a Living Monument to Congress Failure”, Scroll Staff, 27 February 2015, https://scroll.in.

41. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, Scheme at a Glance, https://nrega.nic.in, accessed on 10 July 2024.

42. Our calculation, assuming average annual inflation of 6 percent.

43. Subodh Varma, “MGNREGA: Nearly 1.5 crore Job Seekers Refused Work Till Now”, 23 October 2022, https://www.newsclick.in. “Demand for Work Under NREGA Declines in FY23”, 28 April 2023, https://www.financialexpress.com.

44. Sindhu Bhattacharya, “No Unemployment Allowance, Delayed Payments, Paucity of Work: Parliamentary Panel Decries State of MGNREGS”, 11 February 2022, https://www.moneycontrol.com; Shreehari Paliath, “Rural Jobs Programme Remains Underfunded Despite High Demand”, 24 April 2024, https://www.indiaspend.com.

45. Shreehari Paliath, “No Point in India Growing So Fast If Wages Stagnate and Social Spending Is Slashed”, 8 February 2023, https://www.indiaspend.com; Chakradhar Buddha and Laavanya Tamang, “The Advent of ‘App-Solute’ Chaos in NREGA”, 25 June 2022, https://www.thehindu.com.

46. Rajendran Narayanan, Anuradha De, Chakradhar Buddha, “Aadhaar-Based Pay a Bad Idea for MGNREGS”, 29 January 2024, https://www.thehindu.com; Siraj Dutta, “Forcing Jharkhand’s Workers Out of NREGA”, 9 November 2023, https://www.theindiaforum.in; Sobhana K Nair, “Aadhaar-Linked Pay Becomes Mandatory for MGNREGS Workers”, 31 December 2023, https://www.thehindu.com.

47. We discuss these in detail in article 16 (to be published in Janata Weekly).

48. Shreehari Paliath, “Rural Jobs Programme Remains Underfunded Despite High Demand”, op. cit.

49. See: “People’s Commission Calls for National Fertiliser Policy to Reduce Imports, Strengthen CPSEs”, Newsclick Report, 21 December 2022, https://www.newsclick.in.

50. We have published several articles on the advantages of agroecology in Janata Weekly. See for instance: Colin Todhunter, “Lessons in Freedom: Agroecology, Localization and Food Sovereignty”, 9 July 2023; Shreehari Paliath, “‘When I Share a Seed, it Reinstates a Dying Culture’”, 6 November 2022; and many other articles, all available at https://janataweekly.org.

51. Kundan Pandey, “Community-Based Natural Farming Outshines Other Farming Practices in Andhra Pradesh”, 3 September 2023, https://janataweekly.org.

52. “Raising Agricultural Productivity and Making Farming Remunerative for Farmers”, NITI Aayog, 16 December 2015, http://niti.gov.in.

53. Neeraj Jain, “The Three Agriculture Related Bills: Handing Over Control of Agriculture to Foreign Corporations”, 20 September 2020, https://janataweekly.org; “The Kisans are Right. Their Land Is at Stake – Part 2”, RUPE, 14 February 2021, https://janataweekly.org.

54. Shreegireesh Jalihal, “The NRI and Corporate Houses Behind the Farm Laws”, 20 August 2023, https://janataweekly.org.

55. “The Kisans are Right. Their Land Is at Stake – Part 1”, RUPE, 7 February 2021, https://janataweekly.org.

56. Harish Damodaran, “Explained: What Meeting MSP Demand Would Cost the Government”,

30 November 2021, https://indianexpress.com.

57. T.N. Prakash Kammardi, “It is Possible to Ensure Farmers’ Right to Remunerative Prices Through a Legal Recourse”, 28 March 2021, https://janataweekly.org.

58. Amit Bhaduri and Kaustav Banerjee, “An MSP Scheme to Transform Indian Agriculture”, 11 February 2022, https://www.thehindu.com.

(Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.)