Union Budgets 2014 to 2024 – Article 15:

Budget for Dalits, Adivasis and Minorities

Part A: Dalit–Adivasi Budget

The Constitution outlawed the practice of untouchability and discrimination on the basis of caste, and guaranteed that every citizen shall have equality of status and opportunity. Despite this, the Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) continue to face many forms of untouchability practices as well as social, economic and institutional deprivations. Not only that, they are also subjected to the most horrendous atrocities, ranging from abuse on caste name, murders, rapes, arson, social and economic boycotts, to naked parading of SC/ST women, and being forced to drink urine and eat human excreta.

To tackle this discrimination and exclusion, an important step taken by the Government of India in the 1970s was the launching of the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) and Tribal Sub Plan (TSP). The aim was to ensure the flow of targeted funds from the Central Ministries towards the development of the Dalits and Adivasis, so as to bridge the development gap between these communities and the rest of society. The overall vision was to create an enabling environment for greater participation of Dalits and Adivasis in the mainstream economy and society.

The guidelines under these two programmes clearly stated that each Ministry / Department must allocate funds from their Plan expenditure under a separate budget head / subhead for these Sub Plans, and that these allocations as a proportion of the Plan expenditure should be at least in proportion to the share of the Dalits and Adivasis in the total population. According to the 2011 Census, the population share of Dalits is 16.6 percent and Adivasis is 8.6 percent, implying that the allocations for SCSP and TSP out of the total Plan expenditure should be at least this much respectively.[1]

Successive Union and State governments have shown little interest in implementing these programmes. Consequently, actual allocations for these sub Plans never reached the stipulated norm.

The situation worsened with the coming to power of the Modi Government in 2014. The allocations for SCSP and TCP fell to below the low levels of the previous UPA Government — the allocation for SCSP fell from 7.66 percent of the Plan expenditure in 2013–14 A to 7.06 percent in 2016–17 BE, and for TSP fell from 4.86 percent to 4.36 percent over this period (Table 15.1)!

Table 15.1: BJP Government’s Budgetary Allocations for Dalits & Adivasis (Rs. crore)[2]

| 2013–14 A | 2014–15 A | 2015–16 RE | 2016–17 BE | |

| Plan Budget | 4,53,327 | 4,62,644 | 4,77,197 | 5,50,010 |

| Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) | 34,722 | 30,036 | 34,675 | 38,833 |

| SCSP as % of Plan Budget | 7.66 | 6.49 | 7.27 | 7.06 |

| Tribal Sub Plan (TSP) | 22,039 | 19,921 | 20,963 | 24,005 |

| TSP as % of Plan Budget | 4.86 | 4.31 | 4.39 | 4.36 |

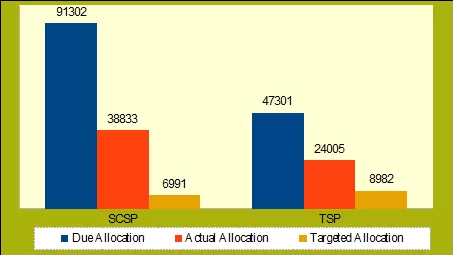

Worse, of the total allocation for SCSP and TSP, only a small proportion of the funds were directed at genuinely benefiting the SC/ST communities. An analysis done by the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR), a democratic secular forum committed to the elimination of discrimination based on caste, found that in the 2016–17 BE, the allocation for SCSP (Rs. 38,833 crore) and TSP (Rs. 24,005 crore) was only 42.5 percent and 50.5 percent of the due allocation respectively. Further, even of this inadequate allocation, only Rs. 6,991 crore, or 18 percent of the total SCSP allocation (and 7.66 percent of due allocation) genuinely benefited the SCs; while only Rs. 8,982 or 37 percent of the TSP allocation (and 19 percent of due allocation) genuinely benefited the STs (see Chart 15.1). A majority of the funds were allocated for schemes and programmes that were very general in nature and had no direct impact on the development of Dalits and Adivasis. Thus, not only was the allocation of funds for these two programmes less than half of the stipulated norm, even this reduced allocation was being done in such a way that allowed the diversion of funds to schemes that did not directly contribute to the actual development of these communities. This was actually a violation of the policy guidelines to these programmes, that clearly state that “SCSP and TSP funds should be non-divertible”.[3]

Chart 15.1: Share of Allocation for SCSP and TSP in Union Budget 2016–17 (BE) (Rs. crore)[4]

DAPSC and DAPST

In 2017, the government merged the Plan and Non-Plan heads of expenditure in the budget. For two years, the Modi Government did not come up with any revised framework for earmarking funds for SCSP and TSP. In the budget papers, SCSP and TSP were now renamed as ‘Allocations for Welfare of Scheduled Castes’ (AWSC) and ‘Allocations for Welfare of Scheduled Tribes’ (AWST), but these allocations were not comparable to the allocations made for SCSP and TSP in the earlier years. They were merely rough estimates made by various ministries of how much of their budgetary allocations were directed towards benefiting SC–ST communities. And so, predictably, allocations for the benefit of these communities as a percentage of total budget outlay further declined.[5]

In 2018, the Niti Aayog finally came up with new guidelines for allocation of dedicated funds within each Ministry / Department for the welfare of SC/ST communities. SCSP and TSP were now renamed as Development Action Plan for SCs (DAPSC) and Development Action Plan for STs (DAPST) [though the Union Budget papers continue to call these plans ‘Allocations for Welfare of Scheduled Castes’ and ‘Allocations for Welfare of Scheduled Tribes’]. These guidelines define for each Ministry / Department the percentage of the allocation for Central Schemes and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CS+CSS) that have to be earmarked as funds for DAPSC (or AWSC) and DAPST (or AWST).[6]

The earlier guidelines for SCSP called for earmarking 16.2 percent of the total Plan outlay in the Union Budget for the Scheduled Castes (this was the proportion of the SC population to the total population); while the TSP guidelines mandated governments to earmark for the Scheduled Tribes 8.2 percent of the total Plan outlay. The new guidelines issued by the Niti Aayog stipulate that 14.9 percent of the total allocation for CS+CSS should be earmarked for DAPSC, and 8.3 percent be earmarked for DAPST.[7]

Since the 2019–20 Union Budget, on the basis of these guidelines, 43 Ministries and Departments have been making allocations for benefiting SC/ST communities within their schemes. The total number of schemes within which these allocations have been made run into several hundred — in 2019–20, 315 schemes had earmarked allocations for AWSC, and 324 schemes had done so for AWST; in 2024–25, this number was 275 and 281 respectively. The problem is, most of these allocations have nothing to do with benefiting SC/ST communities; the concerned Ministries / Departments have made this claim only to do lip service to the targets set out by the Niti Aayog. Only a few schemes genuinely benefit these most oppressed communities of Indian society. According to an assessment made by the NCDHR, in 2019–20, only 89 out of 315 schemes mentioned in AWSC and 21 out of 324 schemes mentioned in AWST had the potential of directly benefiting SC/ST communities; the rest were only general schemes. Likewise, in 2024–25 BE, only 38 out of 275 schemes under AWSC and 45 out of 281 schemes under AWST can be considered to be targeted schemes benefiting SC/ST, the rest are all general schemes.[8]

The NCDHR has made an assessment of the allocations that the various ministries need to make for benefiting SC/ST communities as per the Niti Aayog guidelines, and the actual allocations made. It has also made an assessment of how much of the allocations genuinely benefit SCs/STs — it calls these targeted allocations. The first budget to allocate funds according to the new Niti Aayog guidelines was the 2019–20 budget. We give this data for Scheduled Castes in the six budgets since then (2019–20 to 2024–25) in Table 15.2. As can be seen from the table, the targeted allocations constitute on the average only 22 percent of the due allocations.

Table 15.2: Scheduled Castes Budget: Due, Allocated and Targeted, FY20–FY25

(Rs. crore) [9]

| Financial Year | TotalCS+CSS(1) | Due Allocations as per Niti Aayogguidelines (2) | (2) as % of (1) | Actual Allocationfor SCs (3) | (3) as % of (1) | TargetedSchemes for SCs (4) | (4) as % of (1) |

| 2019–20 BE | 951,334 | 141,309 | 14.9% | 81,341 | 8.6% | 34,833 | 3.7% |

| 2020–21 BE | 8,98,430 | 1,39,172 | 15.5% | 83,257 | 9.3% | 16,174 | 1.8% |

| 2021–22 BE | 10,81,427 | 1,61,260 | 14.9% | 1,26,259 | 11.7% | 48,397 | 4.5% |

| 2022–23 BE | 12,30,836 | 1,82,976 | 14.9% | 1,42,342 | 11.6% | 53,795 | 4.4% |

| 2023–24 BE | 14,19,910 | 2,03,991 | 14.4% | 1,59,126 | 11.2% | 30,475 | 2.1% |

| 2024–25 BE | 14,64,479 | 2,14,109 | 14.6% | 1,65,493 | 11.3% | 46,192 | 3.2% |

| Total | 70,46,416 | 10,42,817 | 14.87% | 7,57,818 | 10.62% | 2,29,866 | 3.28% |

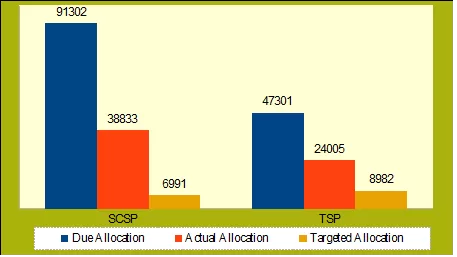

In Chart 15.2, we present this data in graphic format. It gives the targeted allocation for benefit of Dalits as a percentage of due allocation for AWSC as per Niti Aayog guidelines. As can be seen from the chart, this percentage has fluctuated between 11.6 and 30 percent. Chart 15.2 also gives the gap in absolute numbers for each of the six years. The total loss to the Scheduled Castes because of this non-compliance with Niti Aayog guidelines over the six-year period 2019–20 to 2024–25 is Rs. 8.13 lakh crore.

Chart 15.2: Scheduled Castes Budget: Targeted Allocation as % of Due Allocation and Total Gap in Allocation for SC, FY20–FY25 (Rs. crore) [10]

In Table 15.3, we give the assessment made by the NCDHR of how much of the allocations made for AWST genuinely benefit the Scheduled Tribes over the period 2019–20 to 2024–25. The table shows that the targeted allocations constitute only 31% of the due allocations.

Table 15.3: Scheduled Tribes Budget: Due, Allocated, Targeted, FY20–FY25

(Rs. crore) [11]

| Financial Year | TotalCS+CSS(1) | Due Allocations as per Niti Aayogguidelines (2) | (2) as % of (1) | Actual Allocationfor STs (3) | (3) as % of (1) | TargetedSchemes for STs (4) | (4) as % of (1) |

| 2019–20 BE | 947,228 | 76,592 | 8.1% | 52,885 | 5.6% | 21,628 | 2.3% |

| 2020–21 BE | 8,95,043 | 77,034 | 8.6% | 53,653 | 6.0% | 19,428 | 2.2% |

| 2021–22 BE | 10,77,460 | 88,077 | 8.2% | 79,942 | 7.4% | 27,830 | 2.6% |

| 2022–23 BE | 12,26,282 | 98,664 | 8.0% | 89,265 | 7.3% | 43,586 | 3.6% |

| 2023–24 BE | 14,18,244 | 1,15,672 | 8.2% | 1,19,510 | 8.4% | 24,384 | 1.7% |

| 2024–25 BE | 14,63,079 | 1,22,400 | 8.4% | 1,24,909 | 8.5% | 41,730 | 2.9% |

| Total | 70,27,336 | 5,78,439 | 8.25% | 5,20,164 | 7.2% | 1,78,586 | 2.55% |

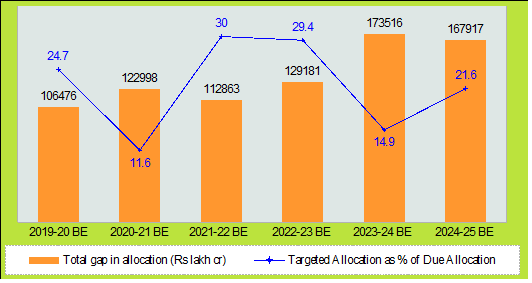

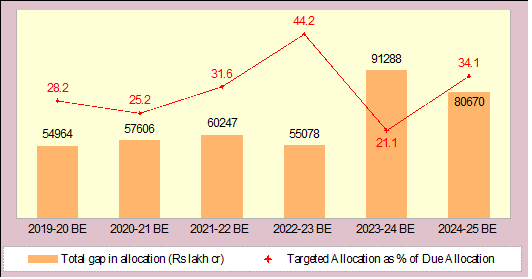

We present this gap between the targeted allocation and due allocation for Scheduled Tribes in graphic format in Chart 15.3. The total loss to the STs because of the unwillingness of the various ministries and departments to follow the spirit of the Niti Aayog guidelines is Rs. 4 lakh crore.

The loss to the SC and ST communities because of lack of concern of the Modi Government towards these most oppressed sections of the Indian society totals Rs. 12.12 crore! To put this amount in perspective, it constitutes one-fourth of the total budget outlay for this year.

Chart 15.3: Scheduled Tribes Budget: Targeted Allocation as % of Due Allocation and Total Gap in Allocation for ST, FY20–FY25 (Rs. crore) [12]

Allocation for DSJE and MoTA, FY15–FY25

The data that best reflects the total unconcern of the Modi Government for the condition of Dalits and Adivasis is the budget allocation for the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment (DSJE) and the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA). As per the guidelines for DAPSC&ST, the DSJE is supposed to take the lead role in monitoring the implementation of DAPSC, and the MoTA is the nodal ministry for DAPST. But the Modi Government has slashed the budget outlay for DSJE and MoTA to very low levels!

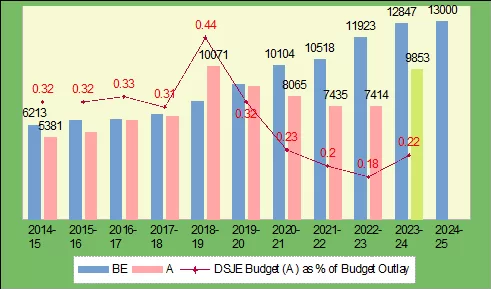

Chart 15.4 gives the budget allocation (BE) and budget spending (A) for DSJE for the 11 Modi budgets presented so far.

Chart 15.4: Department of Social Justice and Empowerment: BE and Actuals, FY15–FY25 (Rs. crore)

Note: For 2023–24, the figure is RE, not Actuals.

As the chart shows, while the budget estimates have seen a continuous increase in recent years to Rs. 13,000 crore in 2024–25 BE, actual spending has continuously declined even in nominal terms — from Rs. 10,071 crore in 2018–19 A to Rs. 7,414 crore in 2022–23 A. Over the 8-year period 2014–15 A to 2022–23 A, actual budget spending of DSJE has increased at an average annual growth rate of only 4.1 percent,[13] which means a decline in real terms. The actual budget spending of the DSJE is so small that as a percentage of total budget outlay, it was a miniscule 0.18 percent in 2022–23; not only that, it has fallen by 44 percent over the period 2014–15 to 2022–23 (from 0.32 percent to 0.18 percent — see Chart 15.4).

For 2023–24, the revised estimates for DSJE show a significant increase to Rs. 9,853 crore. Considering the attitude of the Modi Government towards this department during the previous 9 budgets, in all probability, the actual spending should be much less (we will know this figure in the next year’s budget papers)

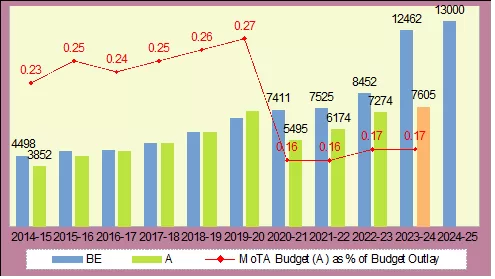

Chart 15.5 gives the budget estimate and actual spending for the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA). For this ministry too, budget estimate has increased to Rs. 13,000 crore in 2024–25 BE. Last year, the BE was Rs. 12,462 crore, but RE is only Rs. 7,605 crore. Therefore, in all probability, actual spending for 2024–25 should turn out to be about the same as 2023–24 RE and 2022–23 A (Rs. 7,274 crore). Like for DSJE, for this ministry too, the budget spending in 2023–24 RE is a tiny 0.17 percent of the total budget outlay. This figure was 0.23 percent in 2014–15; implying a reduction of 26 percent over this 10-year period.

Chart 15.5: Ministry of Tribal Affairs: BE and Actuals, FY15–FY25 (Rs. crore)

Note: For 2023–24, the figure is RE, not Actuals.

Allocation for Welfare of SCs in 2024–25 BE

Let us now take a closer look at AWSC in this year’s budget papers. As given in Table 15.2 above, only 3.2 percent (Rs. 46,192 crore) of the total allocation for Central Schemes and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (Rs. 14.64 lakh crore) is targeted towards genuinely benefiting the Scheduled Castes, in contrast to the Niti Aayog guidelines that call for an allocation of 14.6 percent.

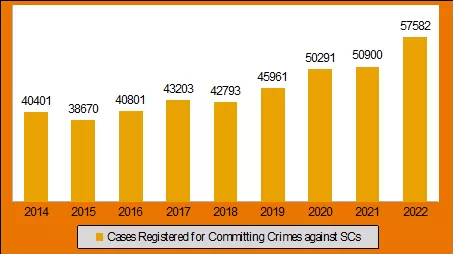

Crimes against Scheduled Castes have risen by 42.5 percent during the Modi years. According to data given by National Crime Records Bureau’s report Crime in India, a total of 40,401 cases were registered for committing crime against Scheduled Castes in 2014; in 2022, this number had zoomed to 57,582 cases (Chart 15.6). Particularly distressing is that atrocities against Dalit women have doubled over these 8 years — over the period 2014 to 2022, total registered cases of rape of Dalit women have gone up from 2,233 to 4,241, which means that more than 10 Dalit women are being raped daily.[14] Despite this high crime rate, the Centre has allocated only Rs. 550 crore for the implementation of Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes Prevention of Atrocities Act.

Chart 15.6: Rising Crime Against Dalits, 2014 to 2022 [15]

SRMS and NAMASTE

The ‘Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act’ was passed in 2013 with the objective to end manual scavenging. This act laid down a detailed definition of ‘manual scavenger’ as an individual engaged or employed for manually cleaning or handling in any manner, human excreta. Those persons who clean excreta using devices and protective gears are not deemed as manual scavengers, as per the Act.

However, despite this Act, and several orders by the Supreme Court and High Courts directing the Union Government and State governments to implement it,[16] manual scavenging continues to exist in the country. According to the website of the Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA), a non-profit organisation working to eliminate this inhuman practice, “the practice of manual scavenging continues to exist in many forms. Even the government promotes such an occupation. Workers are employed by the municipalities and the Indian railways to carry out manual scavenging. Manual scavenging is also carried out in private homes and in community toilets.” The website goes on to say that “One of the main reasons for the existence of manual scavenging is usage of dry latrines. According to the 2011 census, there are 26,07,612 dry latrines in India. Manual scavengers are employed in cleaning these latrines.”[17] The data given on the website of SKA indicates that there may be tens of thousands and probably even a few lakh manual scavengers in the country even today.[18] Hundreds of workers continue to die while cleaning sewers, because of lack of protective equipment.[19] According to data compiled by SKA, 43 manual scavengers died in just the six months between 1 February 2024 when the FM presented the interim budget and 23 July when she presented the full budget for 2024–25.[20]

The Modi Government has never been serious about eliminating this practice. The most important scheme in the budget for rehabilitating manual scavengers is the ‘Self-Employment Scheme for Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers’ (SRMS). The total budgetary allocation for this scheme in the 9 budgets from 2014–15 to 2022–23 is Rs. 1,325 crore, but actual spending is less than 20 percent of this — Rs. 242 crore.[21]

In 2023–24, the Centre released a smokescreen. It changed the name of the scheme to “National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem” (NAMASTE). A note on the scheme released by the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment says that the focus of the scheme will be “on prevention of hazardous cleaning and promotion of safe cleaning practices through trained and certified sanitation workers.”[22] Only the name has been changed; the budgetary allocation continues to be paltry — in 2023–24, Rs. 97.4 crore were allocated for the scheme; the revised estimates show a spending of less than one-third, Rs. 30 crore. In 2024–25 BE, the allocation has been increased to Rs. 117 crore; how much will the government actually spend will be known two years later.

Budget Allocation for Education for SC/ST Students

The Ministry of Education claims that that 14.8 percent of its budget allocation is directed towards the benefit of Scheduled Castes, and 8.1 percent towards the benefit of Scheduled Tribes in 2024–25 BE. The Department of School Education and Literacy (DSEL) claims an allocation of Rs. 13,717 crore under AWSC, and Rs. 7,589 under AWST; while the Department of Higher Education (DHE) claims this allocation to be Rs. 4,174 crore and Rs. 2,122 crore respectively.

However, the major part of these allocations is for general schemes, they are not targeted at the welfare of SC–ST students. Thus, within the allocation of DSEL under AWSC and AWST, schemes like Support to Samagra Shiksha, Support to PM POSHAN, Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan, Navodaya Vidyalaya Samiti and PM Schools for Rising India (PM SHRI) have been included which are general schemes, they are not targeted at benefiting SC–ST students. But such schemes constitute 98 percent of the total allocation of DSEL under both AWSC and AWST.[23]

Likewise, the allocation of DHE that is claimed to be directed at benefiting SC–ST students includes schemes like Grants to Central Universities, Support to IITs, University Grants Commission, World Class Institutions and Pradhan Mantri Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan. None of these schemes directly benefit SC–ST students. They constitute 85 percent of the total allocation of DHE under both AWSC and AWST.[24]

The only education schemes that genuinely target SC–ST students are scholarship schemes like the Pre-Matric and Post-Matric Scholarships — for SC students, these schemes come under the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment, and schemes benefiting ST students come under the Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

For SC students, the allocation for Pre-Matric Scholarship has increased from Rs. 209 crore in 2022–23 A to Rs. 430 crore in 2023–24 RE and Rs. 500 crore in 2024–25 BE; for ST students, this has increased from Rs. 357 crore in 2022–23 A to Rs. 412 crore in 2023–24 RE and Rs. 440 crore in this year’s BE.

The allocation for Post-Matric Scholarship for SCs (Rs. 6,360 crore) constitutes 49 percent of the total DSJE budget. For ST students, this scholarship has been allocated Rs. 2,433 crore this year.

Allocation for Welfare of STs: Eklavya Schools

The Modi Government has drastically reduced the budget allocation for the important scheme ‘Development of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups’ from Rs. 256 crore in 2023–24 BE (and zero in the revised estimate) to a mere Rs. 20 crore in 2024–25 BE.

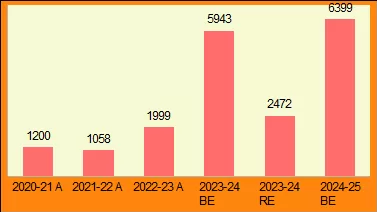

On the other hand, nearly 50 percent of the allocation of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (Rs. 6,399 crore out of Rs. 13,000 crore) has gone to Eklavya Model Residential Schools (EMRS), whose stated aim is to provide quality middle and high-level education to ST students in remote areas. The allocation for these schools has zoomed in the past few years (Chart 15.7).

Chart 15.7: Budget Allocation for Eklavya Model Schools, FY21–FY25 (Rs. crore)

The media is full of articles eulogising this initiative of the Modi Government. But no one is asking, why is the Modi Government —

- which is so unconcerned about the condition of our tribal communities that the actual targeted budget that genuinely benefits them is only 30 percent of the due allocation (for AWST);

- which is so apathetic about the condition of this most marginalised section of our society that the budget for Ministry of Tribal Affairs, the nodal ministry for tribal affairs, is a tiny 0.17 percent of the total budget outlay (in 2023–24 RE);

- which is so disinterested about educating our children that it has slashed the budget for the Department of School Education and Literacy as a percentage of total budget outlay by 45 percent in the eleven Modi budgets presented so far;

— suddenly showing so much interest in educating our tribal children?

Actually, if we closely examine the scheme, it will become evident that the Modi Government is not really interested in providing ALL our tribal children good education. The government plans to open one Eklavya school in every block in the country with more than 50 percent tribal population and at least 20,000 tribal people. It plans to set up 728 EMRSs by 2026. Each school is to have 480 students.[25] This means these schools will have a maximum enrolment of 3.49 lakh students. The total tribal children population (age group 6 to 17 years) is around 2.76 crore.[26] This means that at the most 1.26 percent of our tribal children will get to study in these elite model schools.

Even so, why is the Modi Government so keen on pushing ahead with model schools for Adivasi children? It appears to us that the reason is ideological — the BJP–RSS want to increase their hold over the tribal communities, for which they are seeking to create a tiny educated elite among the tribal people which is imbued with their saffron ideology? What better way to do it than to use state funds for this purpose!

Part B: Minorities Budget

As per the 2011 Census, religious minorities make up 23.39 crore of India’s total population of 121.09 crore (19.28 per cent of the total population). Of these, Muslim total 14.2 percent, Christian 2.3 percent, Sikh 1.7 percent, Buddhist 0.7 percent, Jain 0.4 percent, Other Religions & Persuasions 0.7 percent, and Religion Not Stated 0.2 percent.

Muslims not only constitute the largest section among the minorities (74 percent), their condition is also the worst. By and large, the Muslim community continues to live in conditions of pathetic poverty, comparable to that of Dalits and Adivasis. Indeed, their condition may even be worse off than Dalits, as Muslim Dalits do not have Scheduled Caste status and so do not benefit from the limited affirmative action policies adopted by the State for the advancement of the non-Muslim and non-Christian Dalits.

The dismal condition of the Muslims was well brought out by the Sachar Committee, set up by the Government of India in 2005 to enquire into the social, economic and educational status of the Muslim community in India; it submitted its report to the Prime Minister in November 2006. The committee presented extensive data to establish that: the literacy and educational conditions of the Muslims are below the national average; their representation in Central government jobs and even banks and Central PSUs is abysmally low; their participation in informal sector jobs is higher than the national average while their participation in salaried jobs in both public and private sector jobs is quite low; access of Muslims to bank credit is low and inadequate; and finally, poverty levels among Muslims (31 percent) are much higher than the national average (22.7 percent) and only slightly better than those of SCs/STs (though slightly worse in urban areas).[27]

Unfortunately, the Modi Government, in keeping with its majoritarian ideology, is further marginalising this most marginalised section of Indian society through its economic policies. This is evident from a cursory glance at the minorities budget.

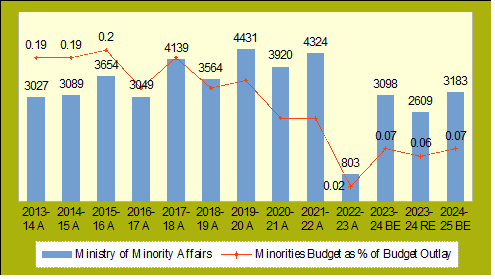

Chart 15.8: Budget Allocation for Ministry of Minority Affairs, FY14–FY25,(Rs. crore)

In January 2006, the Ministry of Minority Affairs (MoMA) was carved out of the Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment to ensure a more focused approach towards issues relating to the notified minority communities, namely Muslims, Christians, Buddhists, Sikhs, Parsis and Jains. During the years of the UPA Government, budget allocation for MoMA increased rapidly, starting from Rs. 144 crore in 2006–07 RE to touch Rs. 3,027 crore in 2013–14 A. Since then, the budget has virtually stagnated, and declined in recent years. The budget spending in 2023–24 RE is just Rs. 2,609 crore, a 14 percent cut even in nominal terms as compared to 2013–14 A! The budget allocation in 2024–25 BE is Rs. 3,183 crore. The sharp decline in the budget allocation for MoMA becomes more evident when we compare it to the total budget outlay. Over the 11 Modi budgets presented so far (2014–15 A to 2024–25 BE), this has fallen from an already tiny 0.19 percent to an infinitesimal 0.07 percent (Chart 15.8).

Clearly, the Modi Government has totally forsaken this ministry — the budget allocation has absolutely no relation to the proportion of the minorities in the population of the country.

In comparison, the budget allocation for the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment is Rs. 14,225 crore. It has more than doubled from its budget allocation of Rs. 5,784 crore in 2014–15 A. Additionally, the Niti Aayog has also issued guidelines asking all Ministries to allocate a certain percentage of their scheme allocations for the welfare of Dalits.

For comparison’s sake, to give an idea of Modi Government’s ideology and priorities, the budget for the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways in 2014–15 A was Rs. 33,048 crore; in 2024–25 BE, it had grown to a huge Rs. 2,78,000 crore, an increase of more than 700 percent. The budget for building roads and bridges is 87 times the budget for improving the condition of one-fifth of the country’s population, the majority of which continues to live in abject poverty.

Allocation for Various Schemes

With such a small allocation for MoMA, obviously all the important schemes within the ministry have tiny allocations. The only scheme that has seen some increase is the Pradhan Mantri Jan Vikas Karyakram (PMJVK). The objective of the PMJVK is to develop socio-economic infrastructure and basic amenities in identified Minority Concentration Areas to improve the quality of life of people in these areas and reduce imbalances as compared to the national average. On the basis of 2011 Census data, around 1,300 minority concentration areas have been identified across the country. Despite the huge geographical area of this scheme, while it was allocated Rs. 1,650 crore in 2022–23 BE, actual spending was only Rs. 223 crore; the allocation has come down to Rs. 550 crore in 2023–24 RE and Rs. 911 crore this year. It only indicates the low interest of the Modi Government in addressing “the development deficits in the selected Minority Concentration Areas”.[28]

Apart from the PMJVK, the Ministry of Minority Affairs has several other schemes, all of which are grouped under three heads: Education Empowerment, Skill Development and Livelihoods, and Special Programmes of Minorities. Most of these schemes have tiddly budget allocations ranging from Rs. 1 crore to Rs. 20–30–40 crore! Clearly, all these schemes exist only on paper:

- Half the budget of the Ministry of Minority Affairs is allocated to Education Empowerment — Rs. 1,573 crore. Of this, the largest part has been allocated to Post-Matric Scholarship. The allocation for it is Rs. 1,145 crore this year, slightly more than last year’s revised estimate of Rs. 1,000 crore. While this sum looks significant, its inadequacy becomes evident if we compare it to the allocation for Post-Matric Scholarship for Dalit students — it is Rs. 6,360 in this year’s budget estimate, nearly six times the budget allocation for minority students, though the population of minorities is more than that of Dalits. Most of the other education schemes have very small budgets, or have been scrapped / have zero budgets. For instance, the merit-cum-means scholarship, which is aimed at supporting meritorious students from poor backgrounds to pursue professional and technical courses, has been allocated only Rs. 34 crore this year — a sharp decline from Rs. 346 crore allocated in 2021–22 A. Between 2014 and 2022, this scheme had benefited over 1.5 lakh new applicants on an average every year.[29]

- The allocation for ‘Special Programmes for Minorities’, which was always very low, has halved over the period 2015–16 to 2024–25. It was Rs. 7.5 crore in 2022–23 A, Rs. 18 crore in 2023–24 RE, and has been allocated a more generous Rs. 26 crore in this year’s BE, same as last year’s BE. This program has the important scheme ‘Hamari Dharohar’, for conservation and protection of culture and heritage of minorities — it has not been given any allocation this year.

- Funds for the minority programme ‘Skill Development and Livelihoods’ have been brought down to a niggardly Rs. 3 crore, from Rs. 499 crore in 2021–22 A, Rs. 245 crore in 2022–23 A and Rs. 64 crore in 2023–24 RE. This head includes schemes like Skill Development Initiatives, Nai Manzil, Upgrading Skills and Training in Traditional Arts/Crafts for Development (USTTAD) and Leadership Development of Minority Women. Most of these schemes have been wound up. The largest scheme under this category used to be Skill Development Initiatives or ‘Seekho aur Kamao’. It aimed to tackle unemployment among minorities by imparting quality skill development training. Its budget has been reduced from Rs. 268 crore in 2021–22 A to zero this year. This is despite the scheme benefiting around four lakh people in seven years till 2021.[30] The programme Nai Manzil helped youth get better employment in the organised sector; while the USTTAD scheme aimed at preservation of traditional crafts — both have no allocation this year. All these programs have been scrapped, despite the fact that in 2016, the Minority Affairs Ministry had included several success stories from these programmes in a report titled “Initiatives and Achievements of two years” released by it.[31] There is also no provision for Central share in the equity of National Minority Finance and Development Corporation; it was granted Rs. 61 crore last year.

- Even within the low budget allocation for minorities, the FM is resorting to subterfuge. In 2023–24, she announced a new scheme for skilling, entrepreneurship and leadership of minorities, called PM-Viraasat Ka Samvardhan (PM VIKAS). Pompous name, duly named after our Prime Minister. The footnote to the programme says that the scheme has components like USTTAD, Hamari Dharohar, Seekho aur Kamao, all of which are also included in the programme ‘Skill Development and Livelihoods’ mentioned above. PM Vikas was allocated a budget of Rs. 540 crore in last year’s BE, the RE show a spending of Rs. 326 crore, and this year’s allocation is Rs. 500 crore. How much will the Modi Government actually spend on this programme we will know in the coming years.

Notes

1. This is well established. See for instance: “Giving Dalits Their Due”, Frontline magazine, 22 January 2014, https://frontline.thehindu.com.

2. For 2015–16 and 2016–17, we have given the RE and BE respectively, as we do not have the Actuals for these years, because the government abolished the classification of Plan expenditure and Non-Plan expenditure in 2017–18.

3. “Planning Commission Guidelines for SCSP and TSP”, cited in: Implementation of Scheduled Caste Sub Plan & Tribal Sub Plan in the Union and State Budgets of India: A Study Report, p. 32, 2011, CBGA, https://www.cbgaindia.org.

4. Dalit Adivasi Budget Watch: 2015 to 2017, National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights–Dalit Arthik Adhikar Andolan, http://www.ncdhr.org.in.

5. Neeraj Jain, “Budget 2018–19: What Is in It for the Common People?”, Janata Weekly, 15 April 2018, https://lohiatoday.com; Article can also be viewed in Archive: April–June 2018, https://janataweekly.org.

6. Guidelines for Earmarking of Funds for Development Action Plan for SCs and STs (DAPSC & DAPST), NITI Aayog, https://www.niti.gov.in.

7. Estimate made by National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights–Dalit Arthik Adhikar Andolan from the new guidelines issued by Niti Aayog on 1 April 2018 available at eUthan Portal, MSJE, GoI (this estimate is given in Table 15.2).

8. Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2024–25, National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights–Dalit Arthik Adhikar Andolan, 23 July 2024, http://www.ncdhr.org.in; and Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2019–20, National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights–Dalit Arthik Adhikar Andolan, May 2019, http://www.ncdhr.org.in.

9. Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2024–25, ibid; and Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2020–21, National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights–Dalit Arthik Adhikar Andolan, February 2020, http://www.ncdhr.org.in.

10. Calculated from data given in ibid.

11. Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2024–25 and Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2020–21, ibid.

12. Calculated from data given in ibid.

13. CAGR. Our calculation.

14. Crime in India, Volume 2, various years, available online at https://www.ncrb.gov.in.

15. Ibid.

16. Tanya Arora, “SC Asks Union, State to Eradicate Manual Scavenging Completely, Ensure Compensation, Rehabilitation and Education”, 30 October 2023, https://cjp.org.in; Mohamed Imranullah S., “Manual Scavenging Continues Despite Groundbreaking Growth in All Fields, Laments Madras High Court”, 29 April 2024, https://www.thehindu.com.

17. Crisis: Safai Karmachari Andolan, https://www.safaikarmachariandolan.org.

18. See also: Pavithra K.M., “The Curious Case of Data on Manual Scavengers”, 3 January 2022, https://factly.in. Two surveys done by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment in 2013 and 2018 identified 58,098 manual scavengers in the country. [Source: Manual Scavenging, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, 7 December 2021, https://pib.gov.in.] After that, the government has not done any survey. But other surveys carried out at around the same time estimated that there were around 50 lakh sanitation workers in India (including toilet cleaners), 20 lakh of whom were working in high-risk conditions.[Source: The Hidden World of Sanitation Workers: Media Briefing, WaterAid, 14 November 2019, https://washmatters.wateraid.org.]

19. See for instance: Pratyush Deep, “Delhi Says It Has No Manual Scavengers. How Have Over 45 of Them Died in 5 Years?”, 27 September 2022, https://www.newslaundry.com.

20. “Despite Unabated Deaths, Manual Scavenging Finds No Mention in Union Budget”, 28 July 2024, https://cms.thewire.in.

21. Our calculation, from Union Budget papers, various years.

22. Budgetary Allocation for Elimination of Manual Scavenging, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, 2 August 2023, https://pib.gov.in; National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE), Department of Social Justice and Empowerment, Updated: 4 November 2024, https://socialjustice.gov.in.

23. Our calculation. We have taken the list of schemes within AWSC and AWST which are general schemes from: Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2024–25, op. cit.

24. Our calculation. We have taken the list of schemes within AWSC and AWST which are general schemes from: Dalit Adivasi Budget Analysis 2024–25, p. 8, ibid.

25. Debabrata Mohanty, “The Opportunity, and Politics, of Eklavya Schools in Tribal Areas”, 21 February 2023, https://www.hindustantimes.com; Eklavya Model Residential Schools, Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 533, To be Answered on – 25/07/2024, https://sansad.in.

26. Data from: UDISE+ Report, 2021–22: Flash Statistics, Table 12.3, https://dashboard.udiseplus.gov.in.

27. Summary of Sachar Committee Report, 7 December 2006, https://prsindia.org.

28. From the footnote to the Ministry of Minority Affairs 2024–25 budget papers.

29. Ashwine Kumar Singh & Sumedha Mittal, “38% Drop in Minority Affairs Budget; Education, Livelihood Schemes Take a Hit”, 21 February 2023, https://www.newslaundry.com.

30. Ibid.

31. Ismat Ara, “How Budget Allocation for Ministry of Minority Affairs Declined”, 12 January 2023, https://frontline.thehindu.com.

(Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.)