The Constitution of India upholds gender equality and empowers the state to adopt affirmative action for empowerment of women. The relationship between reducing gender inequalities and development is now being increasingly recognised by governments worldwide. One of the strategies being used by governments to promote gender equality and women empowerment is gender responsive budgeting (GRB). GRB is an approach to budget making that acknowledges gender inequality in society and allocates funds to implement policies and programmes that promote the development of a more equal society. One of the tools of GRB is the Gender Budget Statement (GBS) that indicates the proportion of total government budget that is being spent on promoting women empowerment and gender equality.[1]

In India, the importance of gender sensitive budgeting as a tool to address gender equality was first recognised in the Ninth Five Year Plan (1997–2002). It initiated the concept of ‘Women Component Plan’, which mandated that at least 30 percent of the plan allocations should be directed towards women empowerment in all women related sectors / ministries, such as Health, Education, Rural Development, Labour and Employment and so on.[2] In 2005–06, the UPA Government took the important step of bringing out the Gender Budget Statement as a part of the Union Budget. Since then, the GBS has been a component of all Union Budgets. It compiles information submitted by the various ministries and departments on how much of their budgetary resources are targeted towards benefitting women.

‘Largest Ever Gender Budget’

In her 2024–25 Interim Budget speech delivered on February 1, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman talked of giving “Momentum for Nari Shakti”. She stated: “The empowerment of women through entrepreneurship, ease of living, and dignity for them has gained momentum in these ten years” and that “these measures are getting reflected in the increasing participation of women in workforce.”

The Economic Survey 2023–24, released a day before the July Budget, stated, “India is transitioning from women’s development to women-led development with the vision of a new India where women are equal partners in the story of growth and national progress.”[3]

The Union Finance Minister followed this up by declaring in her July Budget speech, “For promoting women-led development, the budget carries an allocation of more than Rs. 3 lakh crore for schemes benefitting women and girls. This signals our government’s commitment for enhancing women’s role in economic development.” The next day, every major media outlet in the country highlighted this statement, as proof of the government’s commitment to women-led development.

2024–25 Gender Budget

On paper, the gender budget for FY 2024–25 has indeed seen a substantial increase as compared to last year: from Rs. 2.38 lakh crore in the BE and Rs. 2.75 lakh crore in the RE, it has increased to Rs. 3.27 lakh crore in 2024–25 BE — an increase of more than Rs. 52,000 crore (Table 14.1).

However, a closer look at the GBS in the Union Budget papers of the past 10 years reveals that a large part of the allocations shown under it have actually nothing to do with targeted welfare of women. Let us discuss this with reference to this year’s BE.

Table 14.1: Gender Budget, 2023–24 RE and 2024–25 BE (Rs. crore)

| Gender Budget | Part A | Part B | Part C | |

| 2023–24 RE | 2,75,095 | 83,260 (30.3%) | 1,76,836 (64.3%) | 15,000 (5.5%) |

| 2024–25 BE | 3,27,158 | 1,12,396 (34.4%) | 1,99,762 (61.1%) | 15,000 (4.6%) |

Figures in brackets are percentage of total Gender Budget.

The gender budget is divided into three parts: Part A reflects schemes with 100 percent provision for women, Part B reflects schemes with at least 30 percent allocations for women, and Part C reflects schemes with allocations for women up to 30 percent.

Part A details schemes that are 100 percent aimed at women. The total budget for this is Rs. 1.12 lakh crore this year, and constitutes 34 percent of the total gender budget (Table 14.1). On the face of it, this shows a serious commitment to women-led development. But if we analyse the details of Part A, we find that 85 percent of it is accounted for by only 3 schemes — Pradhan Mantri Avas Yojana (PMAY) (rural and urban), and National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) (Table 14.2). Even if women are given joint ownership of houses built under PMAY (rural and urban), how is this a scheme that is exclusively meant to benefit women? Yet, 100 percent of the budget allocation for PMAY-Rural has been included in Part A (and it constitutes 48.5 percent of Part A).

Table 14.2: PMAY (Rural & Urban) and NRLM in Part A of Gender Budget (Rs. crore)

| Part A of GBS | PMAY-Urban (1) | PMAY-Rural (2) | NRLM (3) | (1+2+3) as % of Part A | |

| 2023–24 RE | 83,260 | 22,103 | 32,000 | 14,129 | 82% |

| 2024–25 BE | 1,12,396 | 26,171 | 54,500 | 15,047 | 85% |

Table 14.3: PMAY-Urban and NRLM in GBS

| 2022–23 BE | 2022–23 BE | 2023–24 RE | ||||

| Location in GBS | GBS allocation as % of total budget outlay of scheme | Location in GBS | GBS allocation as % of total budget outlay of scheme | Location in GBS | GBS allocation as % of total budget outlay of scheme | |

| PMAY-Urban | Part B | 82% | Part A | 100% | Part A | 87% |

| NRLM | Part B | 50% | Part A | 100% | Part A | 100% |

Strangely, PMAY-Urban was earlier in Part B. In the 2022–23 BE, 82 percent (Rs. 22,955 crore) of the total budget allocation of Rs. 28,000 crore was included in the GBS. Then, in 2023–24, it was shifted to Part A, and the revised estimates show that 100 percent of the budget outlay of Rs. 22,103 crore was included in the GBS. In 2024–25 BE, it has remained in Part A, but now 87 percent of it has been included in the GBS (Rs. 26,171 crore out of Rs. 30,171 crore) (see Table 14.3). All this reshuffling has been done, without any change in the guidelines of the scheme. Even more strange is the case of NRLM. In 2022–23 BE, this scheme was included in Part B, and only 50 percent of the total budget allocation was considered to be women-centric (Rs. 6,668 crore out of Rs. 13,336 crore). In 2023–24 BE, this scheme remained in Part B of the GBS. Then, all of a sudden, in 2023–24 RE, without any change in its guidelines, this scheme was shifted to Part A, and now, 100 percent of its budget allocation was included in the GBS (Rs. 14,129 crore). In 2024–25 BE also, 100 percent of the budget allocation for this scheme has been included in Part A (Rs. 15,047 crore) (see Tables 14.2 and 14.3).

Clearly, the bulk of the allocations under Part A of the GBS are a charade.

Part B of the GBS includes spending for those schemes where allocation for women constitutes at least 30 percent of the provision. The total budget for this part is nearly Rs. 2 lakh crore this year (Table 14.1).

More than 75 percent of the allocation under Part B is accounted for by five departments, all of whom claim that 30–50 percent of their budget is exclusively meant to benefit women. The Department of Health and Family Welfare has claimed an allocation of Rs. 36,725 crore for the Gender Budget, which is 42 percent of its total allocation of 87,657 crore; the Department of School Education and Literacy claims a gender-oriented allocation of Rs. 24,946 crore (34 percent of total allocation); Department of Higher Education claims this to be Rs. 15,671 crore (33 percent of total allocation); while the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation has stated this to be Rs. 36,742 crore (47 percent of total allocation). The Department of Rural Development has already contributed substantially to Part A of the GBS (both PMAY-Rural and NRLM come under this department); additionally, it claims that another Rs. 36,484 crore of its budget comes under Part B. But these are just vacuous claims; no ministry ever submits any report on how has it made these claims, how do its schemes exclusively benefit women, how many women have benefited from its women-oriented schemes, nor is any audit ever done to verify these claims.

Part B also includes allocations like an allocation of Rs. 3,975 crore under the Reform Linked Distribution Scheme of the Ministry of Power. This scheme existed in earlier years too, but it never found mention in the GBS. This year, for some reason, the Ministry of Power (or the FM?) decided that over 30 percent of the total allocation of this scheme can be considered an allocation for women.

By such accounting trickery, the total allocation under Part B of the GBS has swollen to Rs. 1,99,762 crore, and it constitutes 61 percent of the gender budget (Table 14.1).

Part C has only one scheme, PM Kisan Samman Nidhi, and the Ministry of Agriculture claims that Rs. 15,000 crore of this fund is directed towards benefitting women (out of the total allocation of Rs. 60,000 crore for PM-Kisan in 2024–25 BE). But no explanation is forthcoming as to how has this claim been made (like whether one-fourth of the fund is being given to women farmers)? Again, it is just a claim.

Therefore, the claim of our FM that “the budget carries an allocation of more than Rs. 3 lakh crore for schemes benefitting women and girls” is humbug. Most of the gender budget, probably more than three-fourths, has nothing to do with benefitting women exclusively. It is another Modi jumla.

Ministry of Women and Child Development

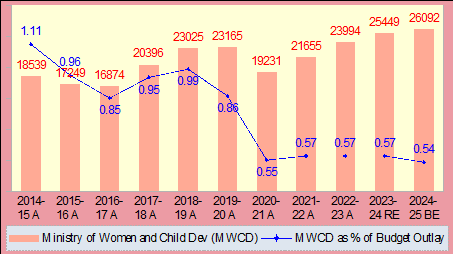

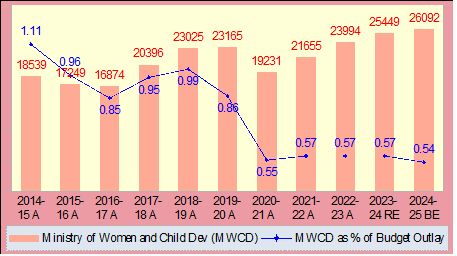

The MWCD is the nodal ministry for the development of women and children. It promotes and monitors the implementation of gender responsive budgeting by other Ministries / Departments. Therefore, budget allocation for this ministry is an important indicator of the Modi Government’s concern for “promoting women-led development.” Unfortunately, over the past eleven Modi budgets, the allocation for this ministry has increased only marginally, from Rs. 18,539 crore in 2014–15 A to Rs. 26,092 crore in 2024–25 BE, which works out to an average annual growth rate of 3.5 percent.[4] This means that the budgetary allocation for this ministry has declined in real terms. This decline in spending is better reflected in the budgetary allocation for MWCD as percentage of budget outlay — it has come down by more than 50 percent, from 1.11 percent of the budget outlay in 2014–15 A to 0.54 percent in 2024–25 BE (see Chart 14.1.)

Chart 14.1: Budget of Ministry of Women and Child Development, FY15–FY25 (Rs. crore)

Genuinely Women Oriented Schemes

Let us now take a look at the few schemes under Parts A and B of the GBS which are genuinely women-oriented schemes.

Ujjwala Gas Yojana (PMUY)

The scheme that has received the most publicity in recent times is the Ujjwala scheme to provide subsidised LPG cooking gas to poor women so as to enable them to transition from traditional cooking fuels such as firewood, coal, cow-dung cakes, etc. to clean cooking fuel. This scheme comes under the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas.

It is an excellent vote-catching scheme, and so the government initially did spend some money on it. At the same time, in keeping with its wont, it got the public sector oil companies to spend hundreds of crores of rupees on an aggressive advertising campaign involving putting up huge hoardings at airports, railway stations, petrol pumps to even bus-shelters across the country publicising the scheme.

According to a reply given in Parliament, as on 30 September 2023, a total of 9.59 crore free connections had been released since the inception of the scheme in May 2016.[5] The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas in a press release claimed that because of the Ujjwala scheme, LPG coverage in the country had jumped to 104 percent as of January 2022, giving the impression that all households in the country now use LPG for cooking.[6]

For the poor to benefit from this scheme on a long term basis, what is important is not just provision of free LPG connections, but also LPG refills at affordable rates. Presently, under the scheme, the beneficiaries are provided a free LPG cooking stove and free first refill. For all subsequent refills (up to 12 refills per year), the government provides a subsidy. However, the price of LPG gas cylinders has soared. Therefore, despite the subsidy provided to PMUY beneficiaries, the rate of subsidised cylinders spiked by 82 percent between January 2018 and March 2023: it was Rs. 496 in January 2018; by March 2023, it had zoomed to Rs. 903. After that, due to electoral considerations, the Centre increased the subsidy, and brought down the cost of a refill per 14.2 kg LPG cylinder for PMUY beneficiaries to Rs. 703 in August 2023 and Rs. 603 in February 2024 (in Delhi).[7]

Poverty in the country is so acute that paying Rs. 600–800 for a LPG refill is unaffordable for most poor women. Consequently, as per data provided by the government in Parliament / RTI data provided by oil companies, as many as one in nine poor families did not take any refill in 2021–22 and 2022–23 (Table 14.4). And as we can see from Table 14.4, 6.37 crore families in 2021–22 and 6.59 crore families in 2022–23 took between zero and 4 refills.

Table 14.4: Number of PMUY Beneficiaries Taking 0–4 Refills in a Year (in lakh)[8]

| Financial Year | No refills | 1 refill | 2 refills | 3 refills | 4 refills | Total |

| 2021–22 | 92 | 161.5 | 148.74 | 130.89 | 103.62 | 636.75 |

| 2022–23 | 118 | 155.81 | 149.24 | 131.19 | 104.27 | 658.51 |

A family of 4–5 persons needs at least 7 to 8 cylinders a year. The total number of PMUY beneficiaries was around 9.34 crore in 2021–22,[9] and it increased to 9.59 crore in 2022–23. This means that at least 60–70 percent beneficiaries continue to use wood or coal for anywhere between 50 to 100 percent of their cooking needs.

Therefore, the claim of the Modi Government that LPG coverage in the country has expanded to 104 percent has little meaning. It is yet another Modi jumla.

MWCD Schemes included in GBS

Most other genuine women-oriented schemes in Parts A and B of the GBS come under MWCD.

MWCD used to have as many as 16 schemes for women’s safety, empowerment and development till 2020–21 (we have excluded schemes funded from the Nirbhaya Fund from this count). Of these schemes, the allocation for 3 schemes, Anganwadi Services, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana and National Nutrition Mission, constituted as much as 98 percent of the total allocation for these 16 schemes (Rs. 17,305 crore out of Rs. 17,675 crore); the total allocation for the remaining 13 schemes was only Rs. 370 crore (all figures for 2020–21 A).

We give below the allocation for some of these schemes in the 2020–21 budget actuals, the last budget in which the actual spending on these schemes is known to us:

- Mahila Shakti Kendra – Rs. 14 cr;

- Swadhar Greh – Rs. 24 cr;

- Ujjawala – Rs. 8 cr;

- Beti Bachao Beti Padhao – Rs. 61 cr;

- Women Helpline – Rs. 13 cr;

- One Stop Centre – Rs. 160 cr;

- National Creche Scheme – Rs. 12 cr;

- Home for Widows (constructed at Vrindavan, Mathura) – Rs. 1 cr;

- Scheme for Adolescent Girls – Rs. 40.82 cr.

In the 2021–22 budget, to cover up the tiny allocation for these schemes, the FM merged all these schemes into 3 umbrella schemes, ‘Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0’, ‘Sambal’ and ‘Samarthya’. In the 2022–23 budget, she again reshuffled these schemes, and also added some new schemes such as ‘Nari Adalat’ that do not find mention in the earlier budget papers. So now we don’t know the amount being spent on Women’s Helpline, or Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, or any other scheme.

Of the total budgetary allocation of Rs. 26,092 crore for the MWCD in 2024–25 BE, more than 80 percent (Rs. 21,200 crore) is for just one scheme, Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, the umbrella scheme directed at providing health, education and nutrition to pregnant and lactating mothers and children. (Of this, Rs. 16,351 crore has been included in the GBS.) We have discussed this scheme in article 12 while analysing the budget outlay for nutrition schemes — its budget has declined in real terms by 32 percent in the eleven Modi budgets from 2014–15 A to 2024–25 BE.

Samarthya has been allocated Rs. 2,517 crore, while Sambal has been allocated Rs. 629 crore, in the 2024–25 budget estimates. (The entire allocation for both these schemes has been included in the GBS.) As can be seen from Table 14.5, actual spending on both these schemes has been much less than the budget estimates during the past two years. In 2022–23, actual spending on Sambal was only 35 percent of the BE, and on Samarthya, it was 82 percent. For 2023–24, the actual spending will be known only in the next year’s budget papers. The revised estimates are 18 percent less than the budget estimates for Sambal and 28 percent less for Samarthya.

Table 14.5: Budget Allocation for Women-Oriented Schemes, FY23–FY25 (Rs. crore)

| 2022–23 BE | 2022–23A | 2023–24 BE | 2023–24 RE | 2024–25 BE | |

| Sambal | 562 | 196 | 562 | 462 | 629 |

| Samarthya | 2,622 | 2,145 | 2,582 | 1,864 | 2,517 |

This means that the Modi Government has further squeezed spending on all the genuine women-oriented schemes that have been subsumed under Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, Sambal and Samarthya.

Most Dangerous Place to be a Woman

In 2018, a poll of global experts on women’s issues conducted by the Thomson Reuters Foundation ranked India as the world’s most dangerous country for women. The respondents were asked where women were most at risk of sexual violence, harassment and being coerced into sex. Afghanistan and Syria ranked second and third, followed by Somalia and Saudi Arabia.

Respondents also ranked India the most dangerous country for women in terms of human trafficking, including sex and domestic slavery, and for customary practices such as forced marriage, stoning and female infanticide.

The poll was a repeat of a survey in 2011, in which experts ranked India as the fourth most dangerous country for women.[10]

The reason why India is being labelled the most dangerous place for women in the world is because India is engaged in outright femicide on its women through practices like sex-selective abortion, infanticide and dowry deaths. According to a 2020 report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the total number of “missing females” in the world over the past 50 years (1970–2020) had gone up to 14.26 crore; of these India accounted for nearly one-third — 4.6 crore. The report estimates that during the past few years (between 2013 and 2017), about 4.6 lakh girls in India were “missing” at birth each year. Missing females are women missing from the population at given dates due to the cumulative effect of postnatal and prenatal sex selection in the past — girls who should have been born and grown up, but have been killed either in the womb or immediately after birth.[11]

Even if the girl survives and grows up, she faces discrimination and lives in fear of being molested / raped all her life. Government data shows reported cases of crimes against women in India rose by 31 percent between 2014 and 2022, when 4.45 lakh crimes against women were registered. This means a crime against a woman is committed every 71 seconds: a woman is molested every 6 minutes, raped every 16 minutes, a case of cruelty committed by either the husband or his relatives occurs every 4 minutes, a woman is kidnapped every 6 minutes, and a dowry death occurs every 81 minutes (all figures for 2022).[12] The above figures are based on reported cases; the actual figures are obviously much more.

And yet, our Prime Minister and Finance Minister, who is herself a woman, do not see it fit to provide a decent budget allocation for schemes to provide assistance, support and rehabilitation to women affected by sexual violence. These include schemes like: Swadhar Greh, which is aimed at providing support and rehabilitation to women in difficult circumstances so that they can lead their life with dignity; Ujjawala scheme for rescuing and rehabilitating women victims of sexual trafficking; Women Helpline to provide 24-hour emergency response to women affected by violence; and One Stop Centre that aims to facilitate access to an integrated range of services including medical aid, police assistance, legal aid/case management, psycho-social counseling and temporary support services to women affected by violence. With little funding, most of these schemes are functioning only on paper. To give an example, while MWCD claims that 752 One Stop Centres (OSCs) are operational in the country,[13] several newsreports that investigated these centres found most of the OSCs to be inaccessible, non-operational and largely unknown to the women they are intended to serve.[14]

Considering the heart-wrenching statistics of female foeticide and infanticide in the country, the least we can expect from our Finance Minister is a decent allocation for the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP) scheme, the most important central scheme targeted at the girl child. The declared aim of the scheme is to end discrimination against the girl child and educate her. The Prime Minister himself launched the scheme in January 2015.

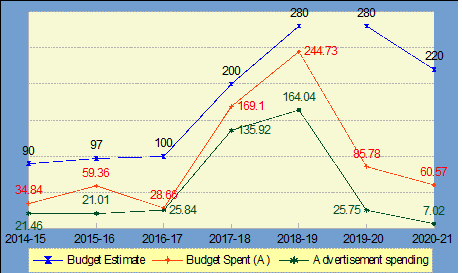

Chart 14.2: Funds Sanctioned, Amount Spent, and Spending on Advertisements Under Beti Bachao Beti Padhao Scheme (Rs. crore) [15]

The funds allocated and spent under the scheme in the 7 Modi budgets from 2014–15 to 2020–21 are given in Chart 14.2. (After that, the Modi government has merged the budget for BBBP scheme with some other schemes into the umbrella scheme ‘Sambal’, so data for BBBP scheme after 2020–21 is not available.) While the total allocation over these 7 budgets is a lowly Rs. 1,267 crore, actual spending is just around half (56 percent) of this, Rs. 683 crore — an average of less than Rs. 100 crore per year. But what is absolutely mind-blowing is that of the total amount spent, nearly 60 percent (Rs. 401 crore) has been spent on advertisements (Chart 14.2)!

Creche Facilities and Working Women Hostels

Before we end this article, let us analyse another women-related announcement made by the FM in her July 2024 budget speech. She stated: “We will facilitate higher participation of women in the workforce through setting up of working women hostels in collaboration with industry, and establishing creches.” This too was much highlighted by the godi media.

If this materialises, this is indeed welcome. But the problem with this initiative is, the Modi Government has put the entire responsibility of implementing this on industry. The Centre has announced no subsidy or financial incentive for the private sector to implement this proposal. Union budget allocation for setting up creches and working women hostels is pathetic. The latest data we have is for 2020–21 A — the spending on Working Women Hostel was a mere Rs. 20 crore (in which not one hostel can be constructed), and the spending on National Creche Scheme was Rs. 11.6 crore. From 2021–22 onwards, these schemes have been merged into an umbrella scheme called Samarthya, whose budget has been declining (we have discussed this above).

This is not the first time the Modi Government has made such an announcement. It had incorporated a similar provision in the Maternity Benefits Amendment Act passed in 2017, which extended the duration of paid maternity leave from 12 to 26 weeks, and also mandated the establishment of crèche facilities in organisations with 50 or more employees in the formal sector. But the government did not allocate any funds to help the private sector implement these provisions; the entire onus of implementing this amendment was put on employers. While public sector corporations like banks and insurance companies implemented the Act, private sector companies avoided taking on this additional financial burden by retrenching women employees. According to a 2020 survey ‘Maternity Benefits (Amendment) Act 2017: Revisiting the Impact’ conducted by the staffing firm TeamLease Services, five sectors — aviation, retail, tourism, real estate and manufacturing — recorded a decline in the share of women in their workforce. It led to net job loss for women of between 13 to 18 lakhs in FY 2018–19 and around 9.1 to 13.6 lakhs in FY 2019–20.[16]

So, if the Finance Minister indeed seriously follows up on her announcement made in the 2024 budget speech and mounts pressure on private sector industry to establish creches and working women hostels, without the government giving any financial subsidy for this, it is only going to lead to yet more job losses for women and a further decline in female workforce participation, which is already among the lowest in the world.

Most importantly, all such announcements have no impact on the condition of 85 percent of our working women working in the unorganised sector. Whether it be the 2017 amendment made to the Maternity Benefit Act, or the latest announcement of the FM on creches, they only benefit women working in the formal sector. Women working in the unorganised sector will only benefit if the FM genuinely increases budget spending on public sector education and health facilities and food & gas subsidy and old age pensions — but as we have seen in the previous articles of this budget analysis series, government spending on these has declined during the Modi years.

The policy measure that will benefit women the most is increasing employment opportunities for them, especially in organised sector jobs. This is of utmost importance to unlock the inherent potential of women. Once women become educated and step outside their home and take up a job, their participation in social production gives them a sense of being an important member of society, they engage with the world and learn to face its challenges, economic independence makes it possible for them to take their own decisions, develop their skills and tastes and develop an independent identity, and all this has a decisive impact on their personality. But as we have discussed in a previous article, the employment schemes announced in the budget — that have been so much praised in the media — are all a farce.

India in the Global Gender Gap Report

Is it therefore any surprise that India ranks at 18th position from the bottom in the Global Gender Gap Index? The Global Gender Gap Index is published annually by the World Economic Forum; it quantifies the gaps between women and men in four key areas: health, education, economy and politics. The 2024 edition of the Gender Gap Index places India at 129 out of the 146 countries surveyed by it. Within South Asia, India ranks behind Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal, and is ahead of Pakistan. Small consolation.[17]

The Modi Government makes tall claims about India developing into an economic superpower. But how can a society develop if half its population is discriminated against and excluded from this development? This had been pointed out by none other than Swami Vivekananda a hundred years ago; unfortunately, even seven decades after independence, his words still ring true:

There is no chance for the welfare of the world unless the condition of women is improved. It is not possible for a bird to fly on only one wing….

In India there are two great evils. Trampling on the women, and grinding the poor through caste restrictions.[18]

An OECD research paper recently attempted to examine gender inequality from a very narrow economistic frame, and quantify the economic costs of gender discrimination. It came up with the staggering estimate that gender-based discrimination in social institutions costs up to $12 trillion for the global economy.[19]

Notes

1. For more on GRB, see: Ritu Dewan and Swati Raju, India Gender Report, Feminist Policy Collective, 2024, https://www.feministpolicyindia.org.

2. Ibid.

3. Economic Survey 2023–24, p. 247.

4. CAGR. Our calculation.

5. Consumption Status Under PMUY, Rajya Sabha Starred Question No. – 76, Answered on 11.12.2023, https://sansad.in.

6. “Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY): LPG Coverage Improves to 104.1% in 2022”, 24 April 2022, https://static.pib.gov.in.

7. Cabinet Approves Continuation of Rs.300 Targeted Subsidy to PM Ujjwala Yojana Consumers, 7 March 2024, https://pib.gov.in; Maitri Porecha, “One in Four Ujjwala Yojana Beneficiaries Took Zero or One LPG Cylinder Refills Last Year Despite Rs 200 Subsidy, RTI Data Reveals”, 31 August 2023, https://www.thehindu.com.

8. For no refills, data from: Maitri Porecha, “One in Four Ujjwala Yojana Beneficiaries Took Zero or One LPG Cylinder Refills Last Year …”, ibid.; “Ujjwala: Over 9 Million Beneficiaries Did Not Refill Cylinder Last Year, Centre Admits”, 3 August 2022, https://www.downtoearth.org.in. For 1–4 refills, data from: Consumption Status Under PMUY, Rajya Sabha Starred Question No. – 76, op. cit.

9. “Ujjwala: Over 9 Million Beneficiaries Did Not Refill Cylinder Last Year, Centre Admits”, ibid.

10. Belinda Goldsmith and Meka Beresford, “India Most Dangerous Country for Women with Sexual Violence Rife – Global Poll”, 26 June 2018, https://news.trust.org.

11. Deepa Narayan, “India Is the Most Dangerous Country for Women. It Must Face Reality”, 2 July 2018, https://www.theguardian.com; “India Accounts for 45.8 Million of the World’s ‘Missing Females’, Says UN Report”, 30 June 2020, https://www.thehindu.com; Against My Will: State of World Population 2020, UNFPA, 2020, https://www.unfpa.org.

12. Calculated by us from data given in: Crime in India 2022: Statistics, Volume 1, NCRB, https://www.ncrb.gov.in.; and: Crime in India 2016: Statistics, NCRB, https://www.scribd.com.

13. A Total of 752 One Stop Centres Operational in the Country Assisting 801062 Women, 6 December 2023, https://pib.gov.in.

14. “Failing Them Again: Beds Remain Empty as One-Stop Centres for Rape Survivors Under Nirbhaya Fund Remain Crippled with Low Referral, Official Apathy”, 18 June 2023, https://indianexpress.com; Srishti Mukherjee and Kumari Rajnandani, “Probing the Reality of India’s One Stop Centres for Women in Distress”, 28 April 2024, https://theprobe.in.

15. Data for 2014–15 to 2020–21: Based on figures given by Smriti Irani, Minister of Women and Child Development, in the Lok Sabha on 10 February 2023. [Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 1511, To be Answered on 10.02.2023, https://sansad.in.] BE for 2021–22 and 2022–23 is not available, as the scheme has been subsumed under the umbrella scheme Sambal. The minister gives the revised estimates for spending under BBBP scheme for these two years in her reply. But advertising expenditure is not available. According to another reply given in the Lok Sabha by Shrimati Irani, for the years after 2020–21, “the component of Media Advocacy has been kept combined for all the sub schemes of Mission Shakti including BBBP.”[Budget Allocation For BBBP Scheme, Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 1762, To be Answered on 16.12.2022, https://sansad.in.]

16. “Maternity Benefits (Amendment) Act 2017: 3 Years Later, Result Far from Satisfactory”, 3 November 2020, https://www.businesstoday.in.

17. Ashwini Deshpande, “Cost of Inequality: What India’s 129 Rank in Global Gender Gap Index Means”, 20 June 2024, https://indianexpress.com.

18. Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Volume 6, Epistles—Second Series, LXXV, 1895, www.ramakrishnavivekananda.info.

19. Gaëlle Ferrant and Alexandre Kolev, “The Economic Cost of Gender-Based Discrimination in Social Institutions”, OECD Development Centre, June 2016, https://www.oecd.org.

(Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.)