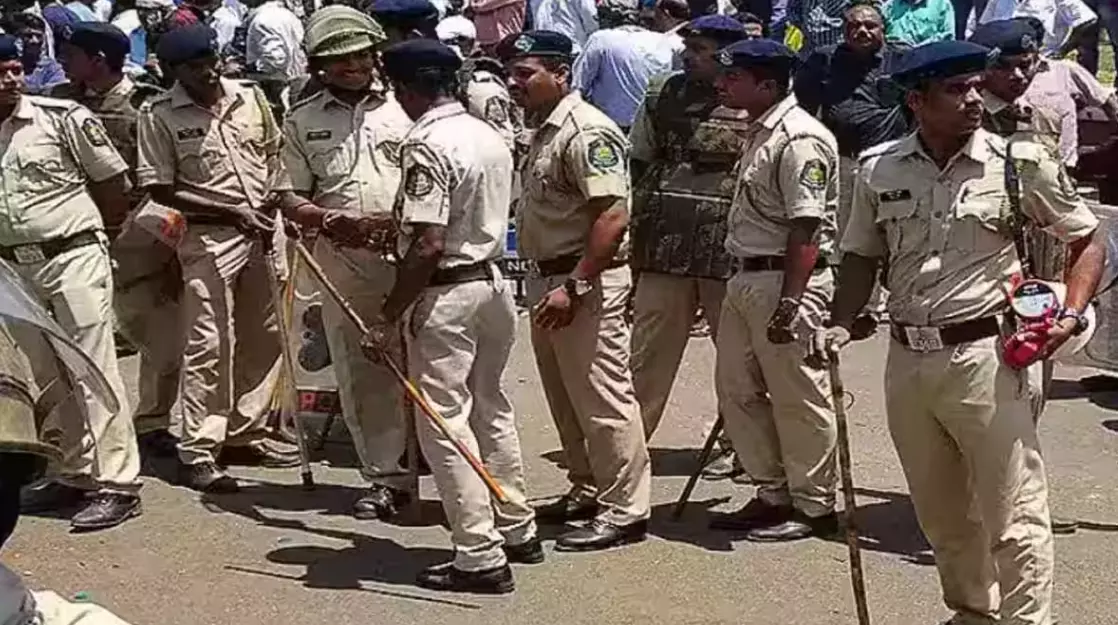

Over the past three years in Bihar, more than 50 Station House Officers (SHOs)—the senior-most officers heading local police stations—have faced disciplinary action for colluding with the very mafias they were supposed to dismantle. These aren’t whispered allegations. The numbers come from official RTI replies, internal police reports, and government records. Together, they reveal a dangerous truth: parts of the law enforcement system are deeply compromised.

Sand and Silence

Drive through Bihar’s riverbeds and the cost of corruption is etched into the earth—deep, illegal cuts carved out by the sand mafia. The trucks don’t stop. The operations don’t hide. And in some districts, neither does the collusion.

In Saran district, a 2024 probe led to the arrest of eight police officers. They weren’t just turning a blind eye to illegal sand mining—they were allegedly collecting bribes to allow it. Some were found with unaccounted cash; others maintained handwritten logs of payments. This wasn’t negligence. It was partnership.

According to an RTI filed by activist Shiv Prakash Rai, over 50 SHOs across Bihar have been suspended, transferred, or formally charged for enabling the illegal sand and liquor trades. Some were caught red-handed; others were exposed after whistleblowers demanded accountability. The most disturbing part? It’s not an exception. It’s the norm.

Liquor Law, Leaks, and Loopholes

In 2016, Bihar banned alcohol. But instead of wiping out liquor, the prohibition birthed a thriving underground economy. From smuggled bottles to backyard breweries, the illegal trade has grown—often aided by those charged with enforcing the law.

In Buxar, liquor worth Rs 40 lakh vanished from police station custody. An internal probe led to the suspension of the SHO and five other personnel. Similar stories have surfaced in Muzaffarpur, Kaimur, and Nalanda, where officers were found either aiding smugglers or accepting bribes to look away.

“The law exists on paper,” said a senior excise official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “But when the enforcers become enablers, even the strongest law collapses.”

Uniform as a Weapon

Perhaps the most chilling stories are those where power was used not for profit, but persecution. In May 2025, in Saharsa, a local youth accused the area SHO of threatening to falsely charge him under NDPS laws unless he paid a bribe. Audio recordings emerged and the SHO was suspended. But for the family, the damage was done. “We raised him to believe police are protectors,” said his father. “Now he won’t even go near a thana.”

These aren’t just administrative failures—they’re human ones, with lasting scars.

A System With Holes

One lesser-known reason behind this corruption is the shortage of official drivers in the Bihar police. Of the 10,000 sanctioned posts, only 3,488 are filled. Many stations rely on private drivers and rented vehicles—creating a dangerous informality.

These drivers have been caught accepting bribes, leaking information, and even acting as intermediaries between officers and mafias. In some cases, it’s outsiders—not trained police—controlling sensitive operations.

What Has the Government Done?

To its credit, the state has taken action. Officers found guilty have been suspended. FIRs have been filed. Inquiries are underway. But experts warn that punishment alone won’t fix a culture of compromise.

What’s needed are structural reforms:

-

Digital FIR registration

-

Body cameras for officers

-

GPS tracking of police vehicles

-

Independent, apolitical oversight bodies

The conversation around police reform can no longer remain theoretical. In Bihar, it’s a matter of survival for the rule of law.

Who Do We Call?

In a just society, a police station is where people run when things go wrong. In many parts of Bihar, people are learning to stay away. When those sworn to protect start protecting illegal profits, the fallout isn’t just in official files—it ripples through entire communities. Trust, once broken, is hard to restore. In villages and towns across the state, that trust is now fractured. The uniform, once a symbol of safety, has become a cause for suspicion.

Until Bihar’s policing system holds itself accountable, the question will remain:

When the protectors cross over, who protects the people?