Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) occupies a singular place in the history of Western music. Though he composed in virtually every genre of his time, it is his operas that most vividly reveal the scope of his artistic imagination. Across a remarkably brief career of scarcely two decades, Mozart transformed 18th-century opera through three principal forms—opera seria, opera buffa and Singspiel—imbuing each with unprecedented musical innovation, psychological depth and dramatic coherence. In so doing, he bequeathed works of lasting power and emotional resonance, ranging from comic masterpieces to profound moral dramas and visionary fairy-tales.

The Context of Mozart’s Operatic Journey

Mozart’s early forays into stage works began with schoolboy operettas and solemn Latin plays, but his first fully fledged opera, Apollo et Hyacinthus (1767), already betrays his flair for melody and ensemble writing. A series of Italian operas followed—Il sogno di Scipione (1771), Lucio Silla (1772) and the youthful but spirited La finta semplice (ca. 1768)—before he embarked on the royal commission La clemenza di Tito (1791).

Yet it was in Vienna, between 1784 and 1791, that Mozart’s operatic genius flowered in full. There, under the aegis of impresario Emperor Joseph II and immersed in a cosmopolitan cultural milieu, he produced the three Da Ponte collaborations (Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte), the grand Die Entführung aus dem Serail and La clemenza di Tito, and finally the visionary German Singspiel Die Zauberflöte.

Opera Buffa Redefined: Le nozze di Figaro and Così fan tutte

Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro, premiered Vienna, 1786) shattered the conventions of comic opera. Based on Beaumarchais’s scandalous play, it was subject to censorship for its satirical portrayal of aristocratic privilege. Yet Mozart and librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte transformed the material into a work of warmth and humanity. Figaro, Susanna, the Count and Countess—each character is endowed with music that mirrors their social station and innermost yearnings. Figaro’s buoyant “Se vuol ballare” exudes cleverness and mischief; the Count’s majestic “Vedrò mentr’io sospiro” reveals wounded pride; while the Countess’s poignant “Porgi amor” conveys dignity and wistful compassion.

Crucially, Mozart’s ensembles—duets, trios and that glorious sextet “Sull’aria”—eschew mere comedy for genuine dramatic synthesis. Harmonies shift with astonishing fluidity; motives pass between voices to illuminate shifting alliances and concealed motives. The result is not merely an entertaining farce, but a psychologically integrated portrait of society’s tensions and affections.

Così fan tutte (Thus Do They All, premiered Vienna, 1790) revisits comic territory—the theme of lovers’ faithfulness under trial—but in darker, more ironic hues. The two male protagonists, Don Alfonso’s philosophical cynicism and Despina’s streetwise commentary combine to stage an elaborate experiment in fidelity. Mozart’s score navigates between laughter and pathos: the cheerful “Soave sia il vento” is tinged with a melancholy undercurrent; Fiordiligi’s arias “Come scoglio” and “Per pietà” juxtapose her supposed constancy with a crisis of conscience. In Così fan tutte, Mozart again exploits ensembles to dramatic effect—trios and quartet numbers circulate motives in ever-shifting combinations, illustrating the fluidity of identity and affection.

The Triumph of Dramma Giocoso: Don Giovanni

Don Giovanni (premiered Prague, 1787) stands as perhaps Mozart’s most enigmatic work. Labelled a dramma giocoso, it blends the comic zest of buffa with the moral severity of seria. The title anti-hero, Giovanni, is both seductive Casanova and impenitent libertine. His liaison with Leporello, his long-suffering servant, provides comic relief—even as the drama hurtles towards the supernatural finale.

Mozart’s score captures this moral duality. Leporello’s catalogue aria “Madamina, il catalogo è questo” sparkles with sardonic wit as he lists Giovanni’s conquests; by contrast, Donna Anna’s “Crudele?” and the Commendatore’s grave overtures imbue the work with tragic heft. The climactic “La ci darem la mano” duet intertwines Giovanni’s seduction with Zerlina’s naïve resistance, showcasing Mozart’s genius in fusing vocal lines to convey shifting power dynamics.

Musically, Don Giovanni is revolutionary: the overture itself traverses darkness and light, foreshadowing drama; the orchestration alternates between humour and menace; and in the final scene, the statue’s ghostly summons and Giovanni’s defiance amount to opera’s earliest foray into the supernatural on this scale.

Singspiel and the Magic of Die Zauberflöte

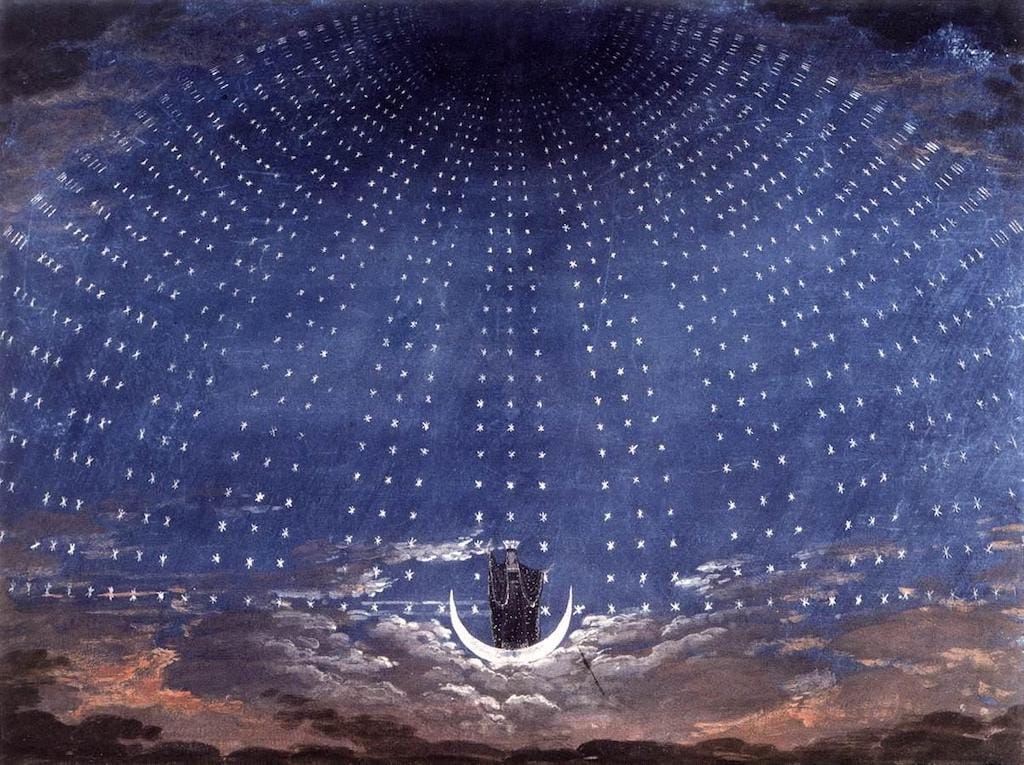

In November 1791—just two months before his death—Mozart unveiled Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), in collaboration with librettist Emanuel Schikaneder. A Singspiel, it incorporates spoken dialogue, popular tunes and Masonic symbolism, yet its mythology rivals any grand opera in profundity. The naive Prince Tamino, his companion Papageno and the Queen of the Night’s icy vengeance set the stage for a journey of initiation, love and enlightenment.

Mozart’s music in Zauberflöte traverses extremes of character: Papageno’s rustic “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” is joyous simplicity; Pamina’s rapturous “Ach, ich fühl’s” touches the sublime; the Queen’s fiendishly demanding “Der Hölle Rache” remains one of opera’s most dazzling displays of vocal pyrotechnics. Yet beyond individual numbers, Mozart weaves a cosmogony of sound: the trials of wind and water evoke colourful orchestral tableaux; the accompanying choruses—Masonic in character—suggest communal transcendence. At once folk-inspired and philosophically profound, Die Zauberflöte stands as Mozart’s final testament to the human capacity for wonder and moral choice.

Opera Seria Revisited: La clemenza di Tito

Completed on commission for the coronation of Leopold II as King of Bohemia, La clemenza di Tito (1791) marks Mozart’s return to opera seria. Critics once dismissed it as conventional, but recent scholarship has reappraised its merits. The libretto by Caterino Mazzolà—adapted from Metastasio—centres on Emperor Titus’s magnanimity towards his conspirators.

Mozart revitalises the form by heightening dramatic continuity and imbuing recitatives with greater tension. The overture’s urgent rhythms propel the drama; Vitellia’s vengeful “Non più di fiori” shatters expectations of regal restraint; and Tito’s renunciation in “Tu fosti tradito” is deeply humane. Through subtle orchestration and carefully wrought ensembles, Mozart transcends the rigid ‘number opera’ formula, giving each scene a sense of organic evolution.

The Hallmarks of Mozartian Opera

Several qualities unite Mozart’s operas and account for their perennial appeal:

- Psychological Veracity

Mozart endowed even secondary characters with individuality. His ensembles are not mere bravura set-pieces, but vehicles for complex interaction: motives pass between voices, reflecting changing allegiances and emotional shifts. - Dramatic Integration

He subordinated rigid forms to the needs of the drama. Arias, duets and choruses emerge organically, driving the plot rather than interrupting it. Recitatives are often orchestrally accompanied to heighten dramatic momentum. - Harmonic Innovation

Mozart exploited unexpected modulations to mirror character moods and narrative turns. In Così fan tutte, for example, sudden shifts to remote keys underscore romantic uncertainty; in Don Giovanni, minor-mode interventions inject menace into ostensibly comic passages. - Orchestral Colour

Though not a late-Romantic orchestrator, Mozart used instrumental timbres with strategic purpose: the basset horn in La clemenza di Tito conveys pathos; woodwind obbligati in The Magic Flute evoke the supernatural; and pizzicato strings often accompany whispered confidences or sly comedy. - Melodic Eloquence

Above all, Mozart’s gift for melody—graceful, flexible and deeply expressive—remains unrivalled. His arias can soar to celestial heights or murmur intimate confession, yet they never feel formulaic.

Legacy and Continuing Resonance

Over two centuries on, Mozart’s operas dominate the standard repertoire. They are staged in every major opera house—often in innovative productions that reinterpret their social and psychological subtexts. Conductors and singers continue to discover fresh depths in Mozart’s scores: period-instrument ensembles shed new light on orchestral balances; historically informed vocal practices renew our appreciation of ornamentation and phrasing; modern directors probe the works’ political, gender and philosophical implications.

Moreover, Mozart’s operatic achievements inspired later composers—Beethoven, Rossini, Verdi and beyond—to pursue greater dramatic realism and musical unity. Even in film and theatre, echoes of Mozartian structure and characterisation abound.

Source:https://serenademagazine.com/mozarts-operas-the-ultimate-study-in-musical-genius/