Music, by its very nature, is ephemeral — a fleeting art form that exists in time. Yet, throughout history, cultures across the world have sought ways to preserve it, communicate it, and transmit it across generations. The story of music notation is thus not only one of technical innovation, but also of cultural ambition — the desire to give permanence to sound. What began as rudimentary signs above religious texts evolved over centuries into an elaborate system capable of conveying the full complexity of Western classical music. Today, music notation continues to evolve in the digital age, shaped by new technologies and global influences.

Early Traces

Before the advent of any formal system, music was transmitted orally. Ancient civilisations such as those in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India developed sophisticated musical cultures, but they relied primarily on aural tradition and memory. There is some evidence, however, of attempts to record music. A Babylonian cuneiform tablet dating from around 1400 BCE describes a form of music theory and contains what may be interpreted as a form of notation for tuning instruments — though it is far from a usable system for performance.

In ancient Greece, music was considered both an art and a science. Philosophers such as Pythagoras explored the mathematical basis of musical intervals, and by the 6th century BCE, Greeks had developed a form of notation that used alphabetic symbols placed above text to indicate pitch. This system allowed melodies to be preserved, though it was largely abandoned after the fall of the Roman Empire.

The Birth of Western Notation

The foundations of modern Western music notation were laid in the medieval monasteries of Europe, driven by the needs of the Christian Church to standardise liturgical chant. Gregorian chant — the sacred music of the Roman Catholic Church — was initially passed down orally, but as the repertoire expanded, the need for a visual aid became pressing.

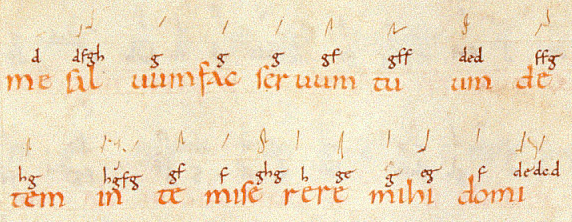

By the 9th century CE, scribes began adding marks known as neumes above the Latin texts of chants. These neumes indicated the general direction of the melody — whether it rose or fell — but not precise pitches or rhythms. They served as mnemonic devices for singers already familiar with the chants.

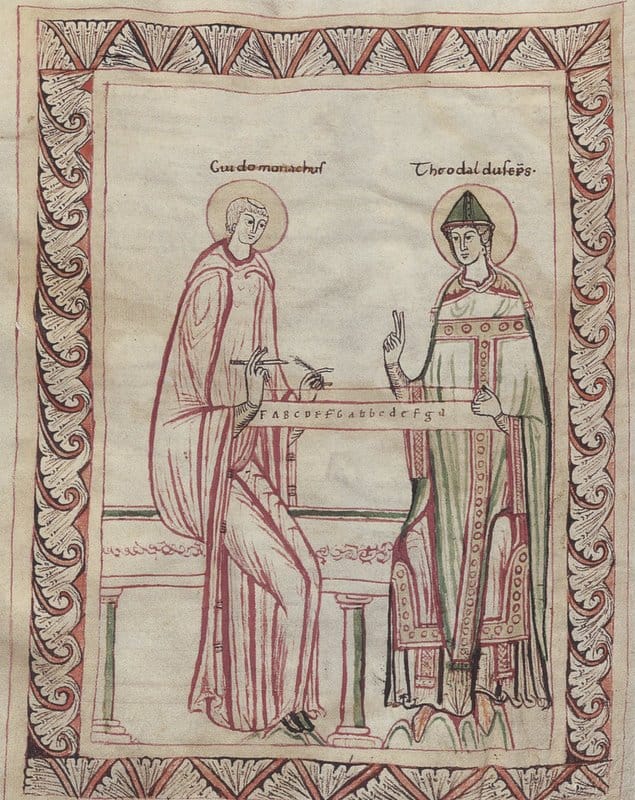

The turning point came in the 11th century with the innovations of Guido of Arezzo, a Benedictine monk. Guido introduced a system of horizontal lines to fix the pitch of notes, using a four-line staff and assigning specific syllables (ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la) to steps in a scale — the origin of the solfège system. His method allowed singers to learn unfamiliar chants with greater accuracy and speed, a remarkable leap in the pedagogy and dissemination of music.

Rhythmic Revolution

While Guido’s system dealt primarily with pitch, the notation of rhythm lagged behind. For centuries, rhythm in vocal music was understood contextually or through poetic meter. It wasn’t until the 12th and 13th centuries — particularly in the schools of Notre Dame in Paris — that composers began to develop ways to indicate rhythm explicitly.

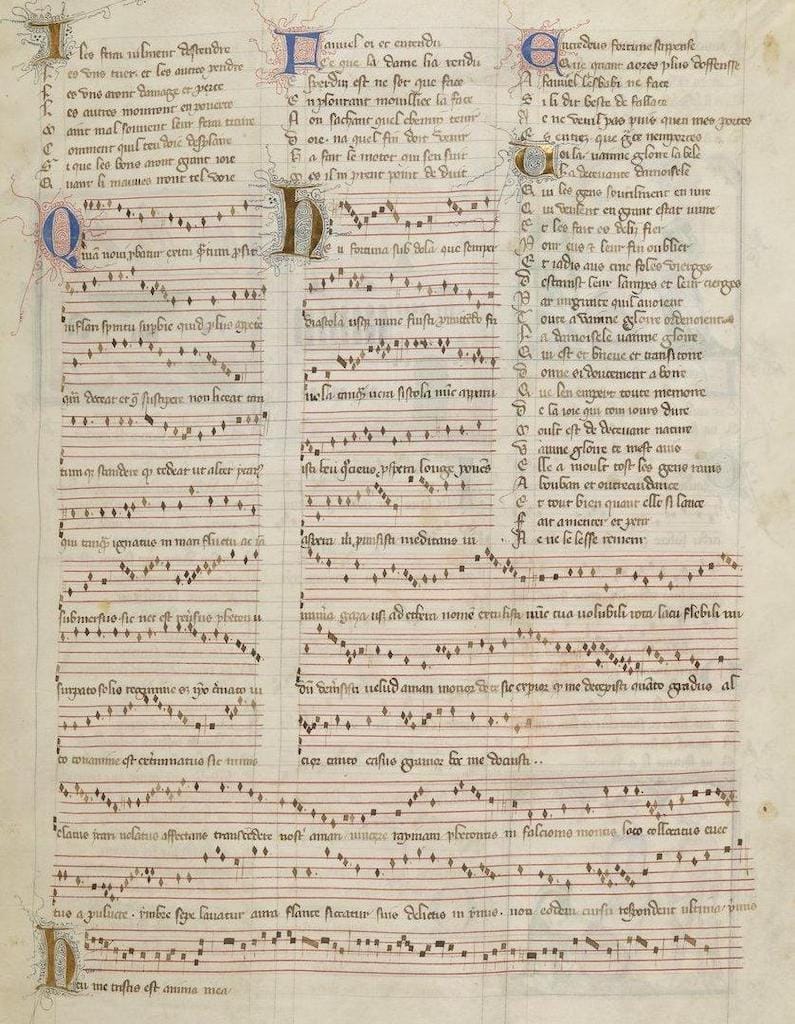

This led to the system of modal notation, which relied on rhythmic patterns called modes (similar to poetic feet) that dictated the duration of notes. Although still imprecise by modern standards, modal notation enabled composers like Léonin and Pérotin to create polyphonic music — music with multiple independent voice parts — that was far more rhythmically complex.

By the 14th century, composers in France and Italy were pushing the boundaries further. Ars Nova (“New Art”), a term associated with the French composer Philippe de Vitry, introduced mensural notation, which allowed for a more flexible and nuanced treatment of rhythm, including duple and triple divisions. For the first time, notation began to reflect the temporal values of notes systematically, giving rise to note shapes that would evolve into the modern semibreves, minims, and crotchets we know today.

Renaissance and Baroque

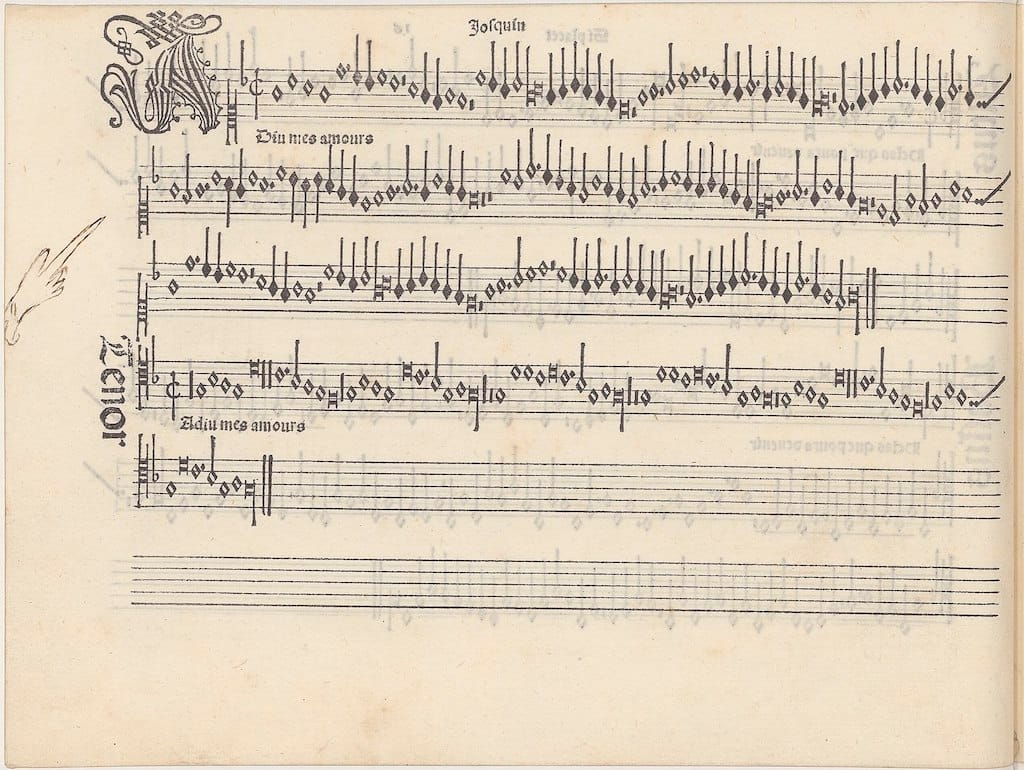

The Renaissance saw a continued refinement of notational practices. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century had a profound effect on music, as it did on literature and science. Ottaviano Petrucci’s Harmonice Musices Odhecaton (1501), the first printed collection of polyphonic music, helped disseminate standardised notation across Europe.

During this period, the five-line staff became standard, and clefs (treble, bass, alto, tenor) were formalised to indicate the relative position of pitches. Time signatures, bar lines, and key signatures also began to emerge, although their use varied between regions and composers.

The Baroque era introduced greater expressive potential into music notation. Composers such as J.S. Bach used complex ornamentation and contrapuntal textures that required more detailed instructions for performers. While some of this was written down, much was still left to the performer’s discretion. The emergence of figured bass — a shorthand system for harmonisation — also illustrates how notation could enable flexibility within a structured framework.

Classical to Romantic

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with composers like Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, the notational system became increasingly precise. Dynamics (e.g. piano, forte), articulations (e.g. staccato, legato), and expressive markings (e.g. dolce, con brio) were regularly used to guide interpretation. The aim was to reduce ambiguity and give the performer a clearer sense of the composer’s intent.

In the Romantic era, this tendency towards detailed notation reached new heights. Composers such as Brahms, Mahler, and Wagner wrote with extraordinary specificity, sometimes including paragraphs of text to accompany their scores. Music notation was now capable of capturing both the structural complexity and the emotional depth of increasingly ambitious compositions.

20th Century and Avant-Garde

The 20th century brought not only new musical languages — such as atonality, serialism, and minimalism — but also new approaches to notation. Composers like Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern extended traditional notation to accommodate twelve-tone techniques, while others, like John Cage, challenged the very notion of fixed scores.

Cage’s graphic scores, for instance, used abstract symbols and images to convey musical ideas, leaving much to the performer’s interpretation. Similarly, composers like Cornelius Cardew and Krzysztof Penderecki developed unconventional notations to represent extended techniques, chance operations, or spatial elements in music.

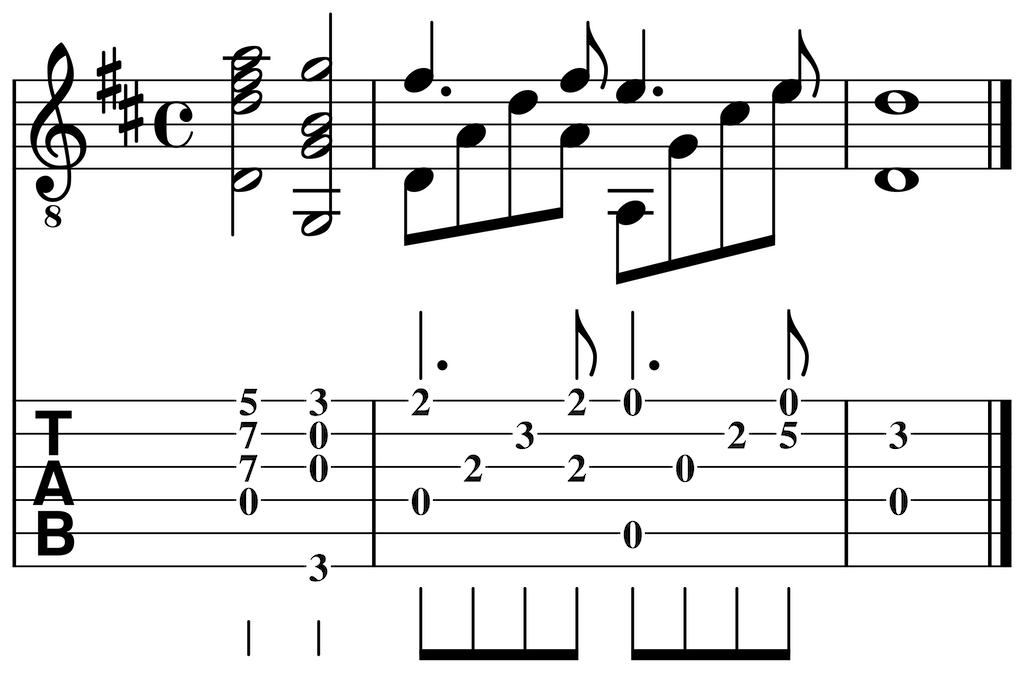

This era also saw the rise of tablature in popular and folk music — especially for guitar — as well as chord charts and lead sheets in jazz and rock, which prioritised harmonic and rhythmic frameworks over precise melodies.

The Digital Turn

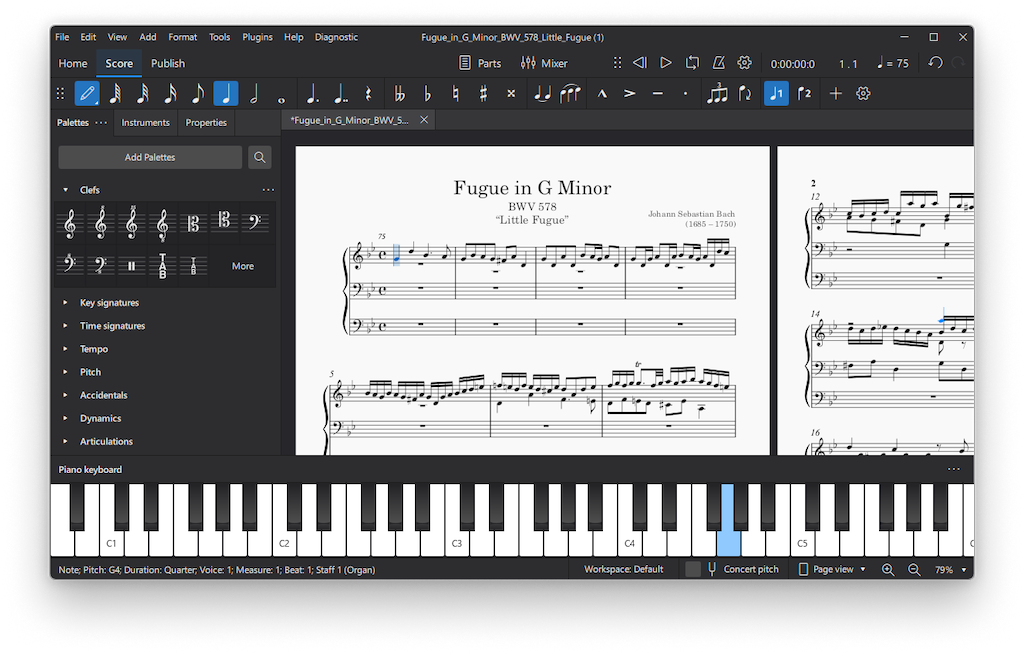

The advent of computers and music software in the late 20th century radically transformed music notation. Programmes like Finale, Sibelius, MuseScore, and Dorico allowed composers and arrangers to write, edit, and print music with unprecedented ease. These tools not only accelerated the notational process but also facilitated collaboration, transcription, and archiving.

Digital notation also enabled playback features, offering immediate audio feedback. For composers, educators, and students alike, this was revolutionary. Moreover, the widespread availability of free software like MuseScore has democratised access to notation tools, breaking down barriers for aspiring musicians across the world.

Beyond traditional notation, the digital age has seen the rise of MIDI and DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations), where sequencing and graphical timelines often replace staff notation. While these systems prioritise performance over readability, they reflect the increasingly diverse ways music is created and consumed today.

The Future of Notation

As we look to the future, the question arises: what role will notation play in an era of AI-generated music, streaming platforms, and real-time performance tools? Some argue that traditional notation, with its Western classical biases, is increasingly irrelevant in a globalised musical landscape. Others see it as a resilient language — a symbolic system that continues to evolve and adapt. Innovations such as interactive scores, haptic feedback, and virtual reality hint at new possibilities for how music might be visualised and learned. At the same time, efforts to notate non-Western music traditions — such as Indian raga, Arabic maqam, or African polyrhythms — suggest a growing desire for inclusive systems that reflect the world’s rich musical diversity.

Source:https://serenademagazine.com/a-complete-history-of-music-notation-from-ancient-symbols-to-digital-scores/