The great auteur was a filmmaking polymath like none other. He was a director, screenwriter, author, lyricist, background narrator, costume designer, art director, sound designer and, of course, a music composer. Starting with his 7th film, ‘Teen Kanya’ (1961), he scored music for all his works, including documentaries. He would also go on to compose music for outside films like Merchant Ivory’s ‘Shakespeare Wallah.’ To celebrate his birth anniversary week, we take a look at his musical career

In Bishoy Chalachchitra (Speaking of Films), a seminal text on film-making, Ray candidly confesses that he is an accidental music composer, a task he took on unhappily, after classical musicians couldn’t deftly create music for his films. For Pather Panchali, for example, Pandit Ravi Shankar recorded extended pieces, which Ray had to cut snippets from to add to his frames. This exercise continued for the next five films with other heavyweights like Ustad Vilayat Khan and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, but Ray noted that it was increasingly becoming a problem. “…Films need precision, maybe a 1.7-second piece or a 23-second interlude. It was becoming a problem to direct the great masters to deliver with that kind of timing…”

His experiments with music started with Devi, his sixth film, for which, although the BGM was by Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Ray composed a lilting Shyama Shongeet. Shyama Shongeet is a semi-classical Bengali genre of spiritual music dedicated to the goddess Kali. Ray’s wife, Bijoya Ray, hilariously notes in her autobiography, Amader Katha (Our Lives), of her coming home one day to have a relative exasperatedly tell her that Ray must have gone mad. He has been blaring Shyama Shongeet all day, singing along with the tracks. This reaction was warranted in a Brahmo family because Ray was an out-and-proud atheist. Not having found any existing Shyama Shongeet that said precisely what he needed in the scene, he wrote and composed one himself. This moment was at the crux of Ray’s approach towards film music–music had to add value to the visual and the narrative, and hence, effective musical components had to be created to make the scene more impactful and full-bodied. The track “Ebaar Tore Chinechhi Ma” (“Now I have finally recognized you”) captures the theme of Devi with caustic irony–the blind deification of human beings without being able to differentiate superstition from sacrosanct. Side note: Ray is still living room conversation because a film from 1960 is shamefully relevant in 2025.

“Ebaar Tore Chinechhi Ma”

From his next film, Teen Kanya, Ray’s anthological tribute to Tagore, he turned music composer for all his films. The music of Teen Kanya and Charulata are fantastic explorations of how Ray moulded Tagore’s music to work for his films. Two stunning examples stand out – In the second story of Teen Kanya, Monihara, Ray expands on the malleability of Tagore’s ‘Baaje Koruno Shurey’ (a song filled with pathos and sorrow), to create the film’s overarching mood of eerie, spooky macabre. In Charulata, it is jaw-dropping to listen to Tagore’s “Mamo Chitte Niti Nritye Ke Je Naache,” a spiritual celebration about god and truth, turn into the background theme for a housewife’s loneliness.

His lifelong obsession with Western classical music gave Ray the foundation to deconstruct Indian genres of music, or set them to a different structure, as heard in the globally-popular version of “Aami Chini Go Chini Tomaare Ogo Bideshini” from Charulata, sung by Kishore Kumar.

“Baaje Koruno Shurey”

“Ami Chini Go Chini”

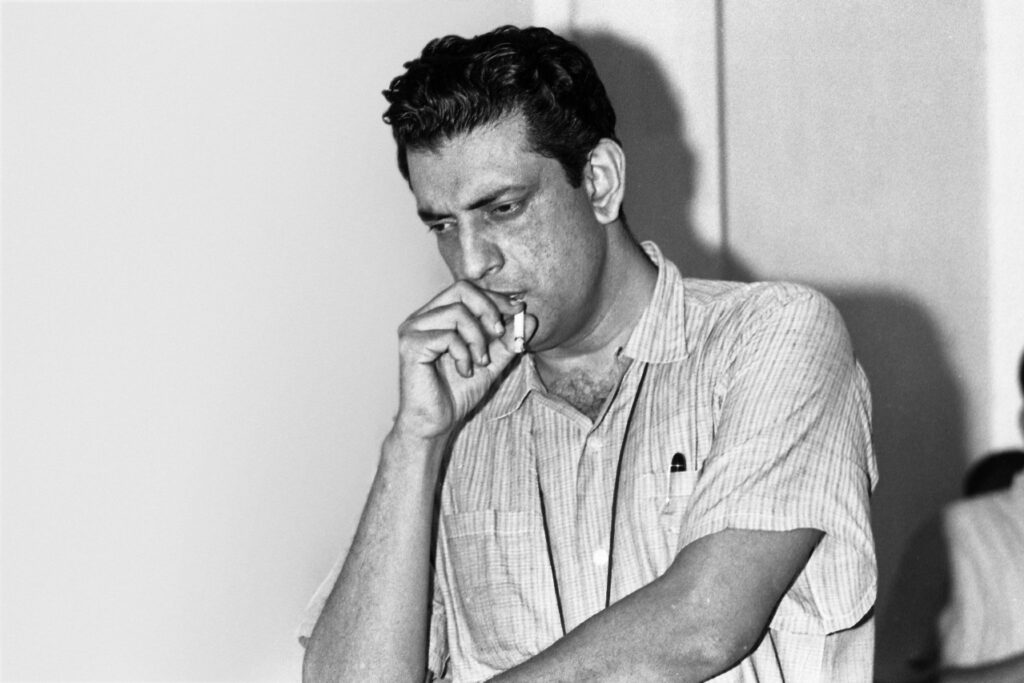

Ray famously said, “…I get too many musical ideas of my own, and composers resent being guided too much.” His teammates and collaborators have often described his jam sessions in their writings, his oscillation between quiet contemplation with an instrument, to maniacal excitement when ideas came to life. Everybody has spoken about Ray anxiously chewing on the corner of a handkerchief till the orchestra got a piece right. This was a young Ray, a have-a-lot-to-prove Ray, too-many-ideas-of-my-own Ray. Ray’s film music amalgamated global styles with Indian sounds. He noted that, for his films, “raga music alone would not do…the average educated middle-class Bengali may not be a sahib, but his consciousness is cosmopolitan…to reflect that, musically you have to blend, do all kinds of experiments…” So, when he finally crafted “Paaye Pori Bagh Mama” for Hirak Rajar Deshe, he turned Hindustani classical music’s upper-crustiness on its head, and created a comic bandish beseeching a tiger to stay put and not attack, masterfully set to Raag Todi. It is a complicated song to perform, but it has filled generations of children and adults with glee.

“Paaye Pori Bagh Mama”

In Hirak Rajar Deshe, Ray also wrote a wonderful Baul song, “Kotoyi Rongo Dekhi Duniyaye,” which is set to the Baul style but has the heart of a protest anthem. He cleverly takes Baul’s melodic, rhythmic, and poetic elements and creates a cutting commentary about the economic divide. I believe Hirak Rajar Deshe is Ray’s most politically-charged film, deserves a top spot in World’s Best lists, and is ironically relevant even today. Ray excelled in using songs to take the story ahead and create an additional narrative layer, almost like a sub-plot for the screenplay. So, while the Baul song in Hirak Rajar Deshe becomes a sub-conversation about the freedom of expression and criticism of authority, in Joy Baba Felunath, he uses a Reba Muhuri bhajan in Braj Bhasha, “Pag Ghungroo Baandh Meera Nachi Re,” to create two perspectives – the bhakts of Machhli Baba, the fake godman, hypnotized by the bhajan during a sabha, like his hokum blinds them, is in contrast to Feluda, Ray’s detective hero, who remains undistracted, as he punishes the criminal. In JBF, Ray uses multiple bhajans to create the mood of Banaras during Durga Puja. The bhajans create the false sense of normalcy everyone is living under, while a sinister plot unfolds.

“Kotoyi Rongo Dekhi Duniyaye”

“Pag Ghungroo Baandh Meera Nachi Re”

Every Ray film can be unpacked and examined from a musical lens, but none will be as exciting as Shonar Kella. A masterclass in the utilisation of regional and folk elements, Shonar Kella, Ray’s other Feluda film, is set completely in Rajasthan, and uses Rajasthani instruments, music, and rhythm to establish a magical world of palaces, deserts, camels, parapsychology, child kidnappers, jewel thieves, and hypnotism. Interestingly, Ray skipped the overfamiliar sarangi for a snappier, percussion-led BGM, that sits perfectly with the sharp murder-mystery that Shonar Kella is. The opening credits is completely set to the Khartal, traditional folk tunes are used throughout the film but in staccato structures, and robust Rajasthani folk songs set the stage for the film’s most crucial sequences.

“Shonar Kella”

I could go on and on, but the auteur always stressed on editing and brevity. So, I should wrap up with saying Ray’s BGMs and OSTs are creative journeys that make for entertaining playlists for movie enthusiasts, while being masterclasses for students of cinema. And, to quote his own lyric: “Maharaja, Tomaare Selaam!” (O King, Many Salutes!)

Arnesh Ghose is a brand consultant, image architect, pop culture columnist, and screenwriter.

Source:https://rollingstoneindia.com/satyajit-ray-as-music-composer/