“Yeh BJP toh bas humari jhuggi ko hattayegi. Humme iss baat ka darr toh hai.” (The BJP will remove our jhuggis. We are scared about this.), says Leela, a dhobi who has lived in Lodhi Colony for 45 years. “Modi has himself said that there will be no jhuggi in Delhi. The people who come to Delhi for work need to live in jhuggis. If they destroy our homes and send us to Noida or Dwarka, how will we come here for work?”

The recent Delhi Assembly election results have sent shockwaves across the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), as party supremo Arvind Kejriwal lost the New Delhi constituency—the very seat where he once unseated former Chief Minister Sheila Dikshit in 2013. Among the communities that were appealed to in the AAP’s campaign was the Dhobi (washermen) community, predominantly belonging to the Scheduled Castes (SC) and considered a long-standing supporter of AAP.

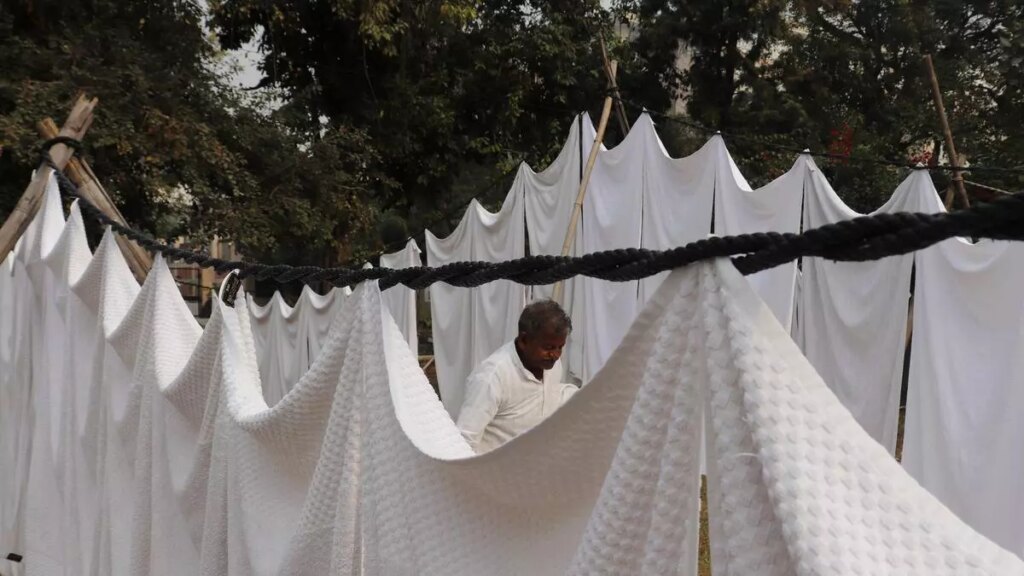

The washers are marginalised, invisible, yet they are tenacious and of huge political importance in Delhi. They have laundered the city’s linen for over 50 years. During its campaigns, AAP pledged “seven guarantees,” to the community, including the creation of a Dhobi Welfare Board, the regularisation of “press” stands, the resumption of the halted licensing process, and domestic-rate charges for power and water. The party had also promised access to quality education, scholarships, skill training for children, and welfare schemes for elderly washermen.

Over the years, several ghats have been modernised: traditional washing by hand was replaced by washing machines; dryers and hydro machines were introduced. But infrastructure has not kept pace with this new technology: drainage is poor, electricity is erratic.

Now, with AAP’s defeat, the community hopes the new government will address their long-pending demands, but they also fear they may not fit into its modernisation plans.

Requests unanswered

Much has changed in the nature of the dhobi community’s work, says Vijay Kumar Kanojia, organising secretary of the Dhobi Employees Welfare Association (DEWA): “But this shift requires space, stable electricity, water, and transportation—none of which are adequately provided.”

License renewal has been particularly problematic, says Karan Kumar, a resident of Ghat 23 in New Delhi constituency. “The government has stopped issuing licenses to us, and if we want to renew our existing licenses, the process gets stuck in the pipeline. They aren’t even transferring the licenses to the next of kin,” he says.

Dhobi ghats, spread across the capital, fall under either the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) or the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD), both responsible for issuing licenses to dhobis of each area. But the community claims that despite repeated applications, their requests remain unanswered.

Also Read | How underprivileged women in a Delhi slum are breaking the glass ceiling

Kanojia explains that while the Congress-era Master Plans had provisions for dhobi ghats near every housing society, no substantial investment has followed since the late 1970s. “Right now, there are around 60 government-operated ghats in Delhi, each with its own ‘pradhan’ (head) elected by the dhobis. But there is no structured government support.”

In 2023, the central government launched the Vishwakarma Scheme aimed to provide toolkits and skill upgradation to people engaged in handicrafts and other small-scale industrial activities, including to washermen. “But without electricity at commercial rates, these machines are useless. The state must ensure infrastructure, not just distribute tools,” says Kanojia.

Frontline reached out to both NDMC and MCD regarding the delay in licenses, but received no response.

Some dhobi ghats remain completely non-mechanised even today. At the ghat on Darbhanga Lane, located near the official residence of Union Minister Nitin Gadkari, most dhobis wash clothes by hand: electricity connections do not exist.

NDMC’s apathy poses enormous challenges to the residents, Anup Kumar, the pradhan of the ghat, tells Frontline. “Our homes were built in the 1970s by the NDMC, and we paid money for them. But today, the NDMC does not hear our pleas for assistance. For instance, our roofs been broken by monkeys, and we requested the NDMC to fix them, with no response. During the monsoon, the roofs leak. At night, the area is pitch dark because there are no streetlights.”

At Lodhi Colony’s dhobi ghat, within the MCD’s jurisdiction, the situation differs slightly. Here, residents say, there is a steady electricity supply, and some improvements were made during the tenure of the former MLA (from AAP); this including the construction of a community washroom, a shaded workspace, and a water cooler. But drainage remains poor, roads are potholed. “During the rainy season, the entire street and even our homes get flooded,” says Leela, 68, a who has lived here for 45 years.

A washerman at the Vivek Vihar dhobi ghat carries hospital bedsheets during the pandemic. New Delhi, June 22, 2020.

| Photo Credit:

SANDEEP SAXENA

Here, the main source of water for washing is a borewell: there is no supply from the Delhi Jal Board, the nodal body for distributing potable water across the capital. Just as in NDMC areas, the dhobis here have received no help with procuring machines. “When I first came here, we washed clothes by hand. Now everyone uses dryers, washers and hydro machines: but we installed them ourselves,” says Leela. “What we need is effective infrastructure, paved roads, clean sewers. Right now, we hire people to clean drains and roads ourselves.”

People in the NDMC area believe that tensions between the former AAP government and the Lieutenant Governor had left their grievances unaddressed. It appears many among the community voted for the BJP for this reason. “People didn’t receive ration cards on time. The public believed that if the Lieutenant Governor was the reason applications were getting delayed, it was better to bring his party to power,” says Ajay Kumar. He explains that while many support Kejriwal’s party, there is a sweeping anti-AAP wave being spread.

Members of dhobi community in Lodhi Colony echo similar sentiments, while acknowledging the work done by AAP. “Kejriwal definitely worked. He developed the Sarvodaya Vidyalayas. The school where I studied used to be a jhopdi (shed), but now it is a four-floor building. My daughter studies there,” says Nitin from Ghat 29 in Lodhi Colony.

Beyond economic and infrastructural challenges, the dhobi community also faces deep-rooted social stigma. “There is no respect for this profession. The word “dhobi” is often used as an insult,” explains Kanojia. He adds that caste-based harassment has grown. “The police are casteist themselves. The cases of harassment don’t get reported and so no steps are taken. There is no survey of our condition. Right now, we are oppressed.”

Also Read | How government neglect left thousands homeless in Delhi’s Tughlakabad

A serious lack of political representation of the dhobi community is a major drawback. Former Bihar minister and senior Janata Dal (United) leader Shyam Rajak, who belongs to the dhobi community, tells Frontline about how his community has been overlooked by all the governments. “In a democracy, numbers matter. Given our population size, we are not taken seriously. That’s why we haven’t seen any schemes to uplift us or address our grievances.”

Delhi has a population of around 10 lakh dhobis, according to some estimates. “If the government truly wants ‘sabka saath, sabka vikaas,’ we would have seen some development in our community,” Rajak adds.

As the political landscape of Delhi shifts, and BJP holds power at both the State and Central levels, the future of the dhobi community remains uncertain, caught between unfulfilled promises, bureaucratic indifference and the threat of displacement.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/politics/delhi-dhobi-ghats-community-casteism-displacement-sanitation-electricity-aap-bjp/article69238506.ece