There is a rainbow on my kitchen counter—scarlet tomatoes, amber-in-the mud potatoes, emperors-in-purple slumming as brinjals, a Mardi Gras frolic of bell peppers mauve, green and gold.

The street below my window is a rainbow surge too, a Moebius strip of shifting hues, a Monday morning world on the move.

I usually resent such parallels, but today’s headlines make this a comparison I can no longer avoid.

That rainbow on my counter is crowded with diversities of colour, texture, taste, terroir. What do you think is their common denominator?

Poison.

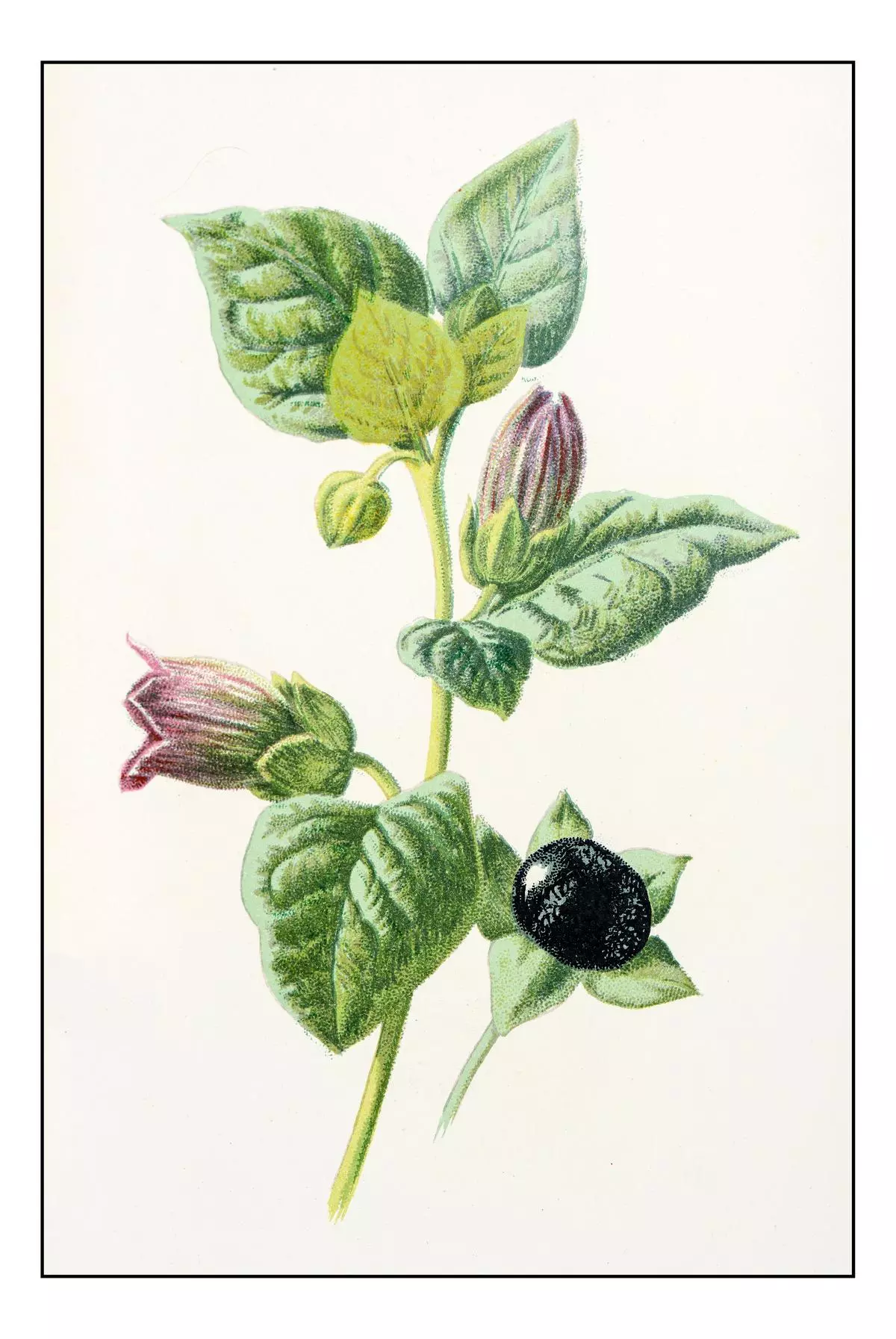

Botanical illustration of Atropa Belladonna (deadly nightshade).

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/ iStock

The rainbow on the street is no different. Judging from our passive endurance of hate and prejudice, for all our visible plurality, our species also has poison as a common denominator.

These vegetables—potato, tomato, brinjal—are common human fodder, but they come from plants that manufacture lethal toxins as defence. They belong in the crowded genus Solanum, which holds more than 1,500 species and is still expanding.

Solanum’s ambiguity is contained in its two common names. Solanum derives from the sun, and implies something warm and nourishing. The other name in the Solanaceae family album is Nightshade, which tells a darker tale. How can we reconcile the two?

Also Read | Snake gourd: A berry in the guise of a reptile

In evolutionary terms, the past is a bad place to be, and that rainbow collection awaiting delectation decided on becoming poisonous as far back as 120 million years ago.

Is evolution cynical?

All poison begins in distrust, and evolutionary studies in plant defences have shown, it is never as simple as that. The distrust originated at an ancient moment of interaction with a perceived enemy; circumstances, climatic and local, defined the enmity. The plant’s defence was against herbivores and insects—we humans hadn’t entered the landscape yet.

****

The world’s most popular Solanum, the potato, was cultivated from wild populations in the central Andes of Peru and Bolivia sometime between 6,000 and 10,000 years ago. So too was an equally ancient Chilean population that arose from the hybridisation of the Andean with a wild species, Solanum tarijense, found in southern Bolivia or northern Argentina. These originals must have been very different in taste and texture from aloo, and would have contained much more of the toxic glycoalkaloids, solanine and chaconine.

Today we only encounter “potato poisoning” when the harvested tubers are stored in bright light and allowed to sprout. The tuber senses an approaching danger and trots out a fresh batch of toxins. A millennium of cultivation has taken the poison out of the potato, and now that the enzyme complex responsible for manufacturing these toxins has been identified, we shall soon be eating potatoes that are entirely innocuous.

The submerged history of the lesser-known Solanums is even more revealing. In the Americas, Asia, and Africa, these endemic plants have long been medicine and food to indigenous populations labelled as “tribal” or aboriginal. For centuries, solanums we dismiss as “toxic” have been processed and consumed safely by these cultures. It is their treasury of knowledge that tomorrow’s medicine must trust.

Fruit and flower of the Dungowan bush tomato.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

The tiny berries of Solanum nigrum (makoa, manathakkali) have been part of Indian cuisine for centuries. The black and red berries pop with tart flavour—but children are cautioned against nibbling the leaves or eating the green berries. The sun-dried berries, fried in a drop of ghee, give a piquant fillip to the most work-a-day sauce or gravy. Poison? No way!

It is in Australia, where new plants are being discovered, that the Solanum really becomes comprehensible. To me these revelations go way beyond botany. They are the new gospels of belief that might yet redeem the stalled evolution of Homo stultus.

On January 20, the new US President declared, in his inaugural address: “As of today, it will henceforth be the official policy of the United States government that there are only two genders: male and female.”

The humble Dungowan bush tomato, from the monsoon tropics of northern Australia, refutes this asinine certainty. “Spiny Solanums” have diversified over the last 10 million years. While the diversity of leaf, flower and fruit is evident to the casual observer, scientists have been so intrigued by its variable reproductive strategies that it has been named Solanum plastisexum.

The plant, discovered 50 years ago, defied classification simply because science refused to accept its changing sexual orientation, or to quote the researchers who deciphered the mysteries of this plant:

Also Read | Tomato: The berry with a wolf

“Some of the confusion surrounding this taxon relates to the botanists’ inability to clearly identify its breeding system due to the species’ non-conformity to any one floral form and/or inflorescence type.

Solanum plastisexum is a new species … (it) is also evidence that attempts to recognise a ‘normative’ sexual condition amongst the planet’s living creatures is problematic. When considering the scope of life on Earth, the notion of a constant sexual binary consisting of distinct and disconnected forms is, fundamentally, a fallacy.”

****

The solanums awaiting my knife compel me to reconsider my own species. If their lethal poisons could be educated by understanding, surely ours can be too? What magic will it require to trick humanity out of the cruelties of caste, the sneering stupidities of religion, the sullen hate of prejudice against language, skin colour and geography?

Solanums, global citizens all, sustain humanity with the plurality of being, their poison transmuted by intelligence. Can we not use our own plurality of being to evolve towards sapience?

Kalpana Swaminathan and Ishrat Syed are surgeons who write together as Kalpish Ratna. They are the authors of Gastronama: The Indian Guide to Eating Right (Roli, 2023).

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/columns/nature-proves-that-the-concept-of-sexual-binaries-is-false/article69210678.ece