Zarina, in her 60s, has lived in her home in Shiv Vihar in North East Delhi for three decades, where she ran a small business making purses. Exactly five years ago, her life changed forever. “I have nothing now. Not even enough money to restart my business.”

The 2020 Delhi riots erupted during a counter-mobilisation against people protesting the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). The clashes ended in the deaths of 53 people, a majority of whom were Muslim; over 500 people were injured. Properties and livelihoods were destroyed. Shiv Vihar was among the worst affected: Countless families were displaced, and homes, businesses, and schools were left in ruins. And livelihoods were lost.

North East Delhi, with a predominantly working-class population, was the epicentre of the riots, one of the worst in the capital’s recent history. Here many people, mostly women like Zarina, operated small garment manufacturing units in their homes, punching belt holes, sewing zippers or trimming threads.

Zarina recalls February 23, 2020 vividly. “My grandchildren were in school.” When she went to pick them up she saw what she believed was “a festival procession”. But then people began running. She witnessed some dying. “The children were terrified”.

Today Zarina’s son is the family’s sole breadwinner, working as a delivery boy. Like many others, she has received no compensation despite filing a case. And she has no hope left.

Also Read | Scarred & scared

Many families, unable to recover from their losses, left the area. As many as 13 homes in her lane were ransacked and damaged during the riots, says Zarina. At least 12 families have moved away, she added. Many sheltered their Muslim neighbours during the violence. “Our Hindu neighbour hid three to four families, apart from us. Another Hindu family sheltered 90-100 people the first night. They even stood outside to protect us. But soon, their own community turned against them. People said, ‘You protected Muslims.’ My neighbour, Kiranpal, replied, ‘Kisne kaha maine musalmano ko rakha hai, maine toh insaaniyat ko rakha hai (Who says I protected Muslims? I protected humanity).’”

But the pressure of social ostracisation from other Hindu families in the neighbourhood was too much to endure. She sold her home soon after the riots and left.

Zarina’s psychological scars still run deep. “Whenever I think about the riots, my heart pounds. I feel like something terrible is going to happen all over again”, she told Frontline. As for her husband, “It broke him”, says Zarina. He passed away two years ago.

Mohammed Shahid just about survived the riots. Accused of murder, rioting and criminal conspiracy, he lost the use of his right arm after a bullet injury. He is still struggling to piece his life back together. His wife, Shaziya Parveen, told Frontline that Shahid’s only fault was being at the wrong place at the wrong time. “He worked as a painter in Punjab and had come to Delhi just to vote. On his way home, a mob suddenly appeared before him. He tried to hide behind a pillar, but that’s when he was shot from the back”.

Shahid was rushed to a nearby hospital, where he was told that riot injury cases were being directed to the GTB Hospital, one of two government hospitals in North East Delhi. “It was only after nine hours at GTB hospital that my husband received treatment. He remained there for 10 days, and the bullet was still not removed. We shifted him to a private hospital where he showed signs of recovery and his surgery was scheduled for later. But then the crime branch came looking for him and took him away”.

Shahid alleges he was not given proper medical attention during his imprisonment and lost his arm due to medical negligence. After spending 19 months in prison, he was granted bail, but his ordeal continues. “We still can’t get proper treatment. He still has bullet splinters in his shoulder. Everywhere we go, doctors say the same thing: ‘It’s a bullet wound, and we can’t treat it—this is a police case’”. The family, with three young children, survives on Shaziya’s meagre earnings as a tailor, working from her home, with some support from NGOs.

Security personnel conduct flag march during clashes in North East Delhi on February 25, 2020.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Muslims were not the only victims. Geeta and her husband, Dalchand, who live in Karawal Nagar, also in North East Delhi, lost valuables worth nearly Rs.1 lakh. “They [the rioters] set the shop on the ground floor on fire. We were tenants on the second floor,” said Geeta. The shop belonged to a Muslim and was attacked, leaving Geeta’s family trapped in a burning house. “The floor became so hot we couldn’t even step on the ground. Our daughter was on the floor above us and fell unconscious due to the heat. We don’t know how we escaped”.

Hindu residents flee

Geeta’s family spent the next three days living on the road in front of their house. “Where else could we go? We had no one. Several other families, both Hindu and Muslim, also spent those days on the streets as their homes burned down. We didn’t eat or sleep for three days. Durso ko marne ke chakkar me apno ko hi maarne lag gye (In trying to kill others, people started killing their own)”, Dalchand told Frontline. The couple has filled out several forms, been through many “inspections” but have not yet received any compensation.

They ran a small business selling potatoes; now Dalchand sells vegetables on a rented cart. “We all lived in harmony. Everyone visited each other’s homes. I don’t know how it came to this”, he told Frontline. Most Hindu families have sold their homes and left the area.

A report released last month by Karwan-e-Mohabbat (Caravan of Love), a people’s campaign that supports survivors of hate crimes with legal, social and livelihood assistance, titled The Absent State: Comprehensive State Denial of Reparation and Recompense to the Survivors of the 2020 Pogrom, explores the failure of both the Central and State governments in providing reparation after the 2020 Delhi communal violence.

Syed Rubeel Haider Zaid, an author of the report, told Frontline, “The compensation and relief processes were designed in such a vague manner that they actively excluded victims rather than providing them support.” Terms such as “relief”, “ex gratia”, and “compensation”, were used interchangeably; and the Delhi government handed its responsibility to the North East Delhi Relief Compensation Commission (NEDRCC)—a commission originally tasked with evaluating property damage rather than ensuring rehabilitation for victims. So, many riot victims never received meaningful aid.

In the immediate aftermath of the violence, the State government disbursed ex gratia relief and death compensation to several families but the overall compensation was a fraction of what the courts had mandated for survivors of the 1984 Delhi riots. In the five years since the riots, no payments have been disbursed to survivors. Thosewho sought medical care at non-government hospitals were denied aid simply because their injuries were not officially recorded in government hospital reports.

Zaid pointed out, “The requirement to file an FIR for a medical-legal certificate discouraged victims, as many feared they would be arrested while approaching the police”. So, several survivors, like Shahid, who had been shot, were not treated promptly, leading to permanent disabilities.

Meanwhile, displacement became an inevitable consequence of the 2020 Delhi riots, as it is with most communal violence. “Many families left Delhi because they felt unsafe or had lost their homes,” Zaid said. However, the government’s assessment of displacement and property loss was deeply flawed. Initially, compensation was only given to landlords, leaving tenants—many of whom were daily wage earners—without financial support. After an appeal, tenants became eligible, but many had already left the city, making it difficult for them to claim compensation.

Also Read | The aftermath of the Delhi riots

The economic devastation was severe; several businesses in riot-affected areas never recovered. “Many people were hesitant to restart their shops because they were waiting for compensation that never came,” Zaid said. Out of the estimated Rs.153 crore in damages assessed, only Rs.21 crore was acknowledged by the NEDRCC. Worse, nearly half this amount was allocated to government property damages, thus reducing the funds available for victims.

The riots also impacted schools in North East Delhi, where most private schools offer classes only up to Class VII (the only government school that offers education up to Class XII is in a Hindu-majority area.) “Many Muslim children stopped going to school out of fear”, said Zaid. The report documents cases where riot-affected students were denied readmission and labelled dangai (rioters). “One student missed his board exams because his house was burned down. When he tried to re-enrol, he was told he would become a rioter anyway and was denied admission”.

Communalism has led to dropouts due to trauma, financial distress and children being forced into work. A social worker engaged with riot-affected families in the area told Frontline that in many households, young girls, even those underaged, were hurriedly married off after the riots just so they could move out of the area. “There are now entire families where no child goes to school because they have started working instead,” Zaid told Frontline.

Five years after the riots, cases filed by the Delhi Police have been dismissed in several instances. More than 2,000 people were arrested during the riots, and 758 cases were registered. Of these, courts have delivered verdicts in 126 cases, with more than 80 per cent resulting in acquittals or discharges due to witnesses turning hostile or failing to support the prosecution’s case.

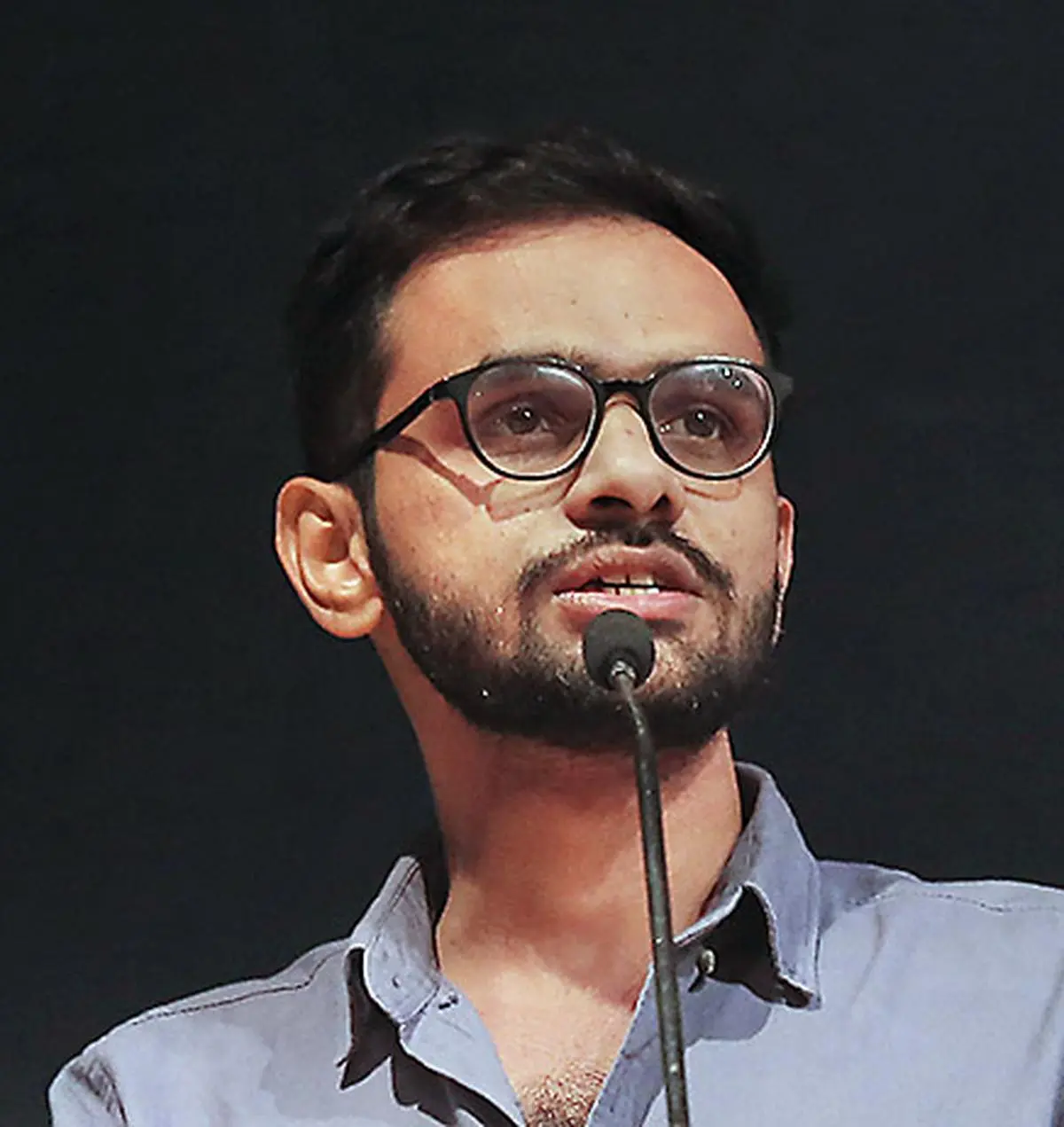

Students leader Umar Khalid remains in prison after the 2020 Delhi riots.

| Photo Credit:

EMMANUAL YOGINI

On February 24, Mohammad Shahnawaz was acquitted in a murder by arson case after the court found major contradictions in the statements of eyewitnesses. He had spent five years in prison. Among those arrested were 18 student leaders and activists charged under the anti-terror law, which restricts access to bail. Only six of them have been released in five years, while others, including Umar Khalid and Gulfisha Fatima, remain in custody awaiting trial.

Human rights activist Harsh Mander told Frontline: “The effort of the police and state machinery appears to be twofold: one, to absolve the perpetrators of violence, and two, to turn the victims into criminals wherever possible. We have seen this happen across cases of lynching, and the Delhi riots are no exception.” When courts declare that someone has been falsely accused, the logical next step should be: full acquittal; compensation for their suffering, and criminal accountability for those who framed them, said Mander. “But we are not seeing that. At best, people are being released after years in jail, with no consequences for those who falsely implicated them.”

Although those accused of inciting violence–such as Kapil Mishra, now Delhi’s Minister for Law and Justice–have only advanced politically, the scars and trauma of the riots still weigh heavily on the victims.

Meanwhile, last Friday, Holi in North East Delhi, was, not surprisingly, one of the most heavily guarded celebrations in recent years. While most of the city was a riot of colours and lights, its streets remained eerily desolate. Security was stepped up, with more motor and foot patrols, and over 25,000 police personnel reportedly deployed. The reason: Holi this year coincided with the second Jummah (Friday) of Ramadan, prompting concerns over potential unrest.

Clearly, the imprint of the 2020 riots has, five years on, not worn off in the national capital.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/society/delhi-riots-2020-survivors-await-justice-compensation-five-years-later/article69344521.ece