“Democracy” in Kashmir rests on two locks: a loose one that guards the occasional ballot box, and a tight one that guards the prison cell. Engineer Rashid has encountered both. The people of Baramulla turned the key on the first, electing him by a landslide. The state, however, holds the key to the second—and has so far refused to turn it.

In February 2025, the Delhi High Court granted Sheikh Abdul Rashid—popularly known as Engineer Rashid—a two-day custody parole to attend the Parliament session on February 11 and 13. This concession, predictably, came with conditions. Rashid was barred from using a mobile phone, prohibited from speaking to the media, and allowed to interact only with designated officials. Even so, he used his fleeting presence in the Lok Sabha to raise concerns over the recent deaths of two civilians in Jammu and Kashmir, allegedly at the hands of security personnel. He called for investigations. For accountability.

More recently, Rashid petitioned the Delhi High Court to waive a newly imposed financial barrier: daily travel expenses of Rs.1.45 lakh to attend Parliament from March 26 to April 4. Democracy in Kashmir, it seems, now comes with a price tag—Rs.8.74 lakh for six days of representation that the court declined to urgently address.

This was not Rashid’s first encounter with the peculiar decorum of Indian democracy. He had already made history in 2024 by winning the Baramulla Lok Sabha seat from behind bars—defeating none other than the current Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Omar Abdullah. But winning an election and being permitted to function as an elected representative are, as any astute observer of Indian politics knows, entirely different matters—especially in the case of Kashmir.

Also Read | If I am a BJP man, then why did BJP put me in jail?: Engineer Rashid

When his name was called in Parliament on July 5, 2024, Rashid did not rise from a legislator’s bench. He entered the chamber under heavy police escort, granted a two-hour custody parole to take his oath as Member of Parliament. On his request, the court allowed his wife and children to be present—provided they produced valid identification. The terms of his parole were as stringent as they were symbolic. No phone. No conversations beyond the assigned officials. And, above all, no media interactions. His hands were unshackled, it seemed, only for the sake of optics.

His offence? Not one proven in a court of law, but an accusation under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

UAPA: Blurred lines

This is not just about Rashid. It is about the law that enabled his arrest—one repeatedly invoked in Jammu and Kashmir, often blurring the line between justice and prolonged incarceration without trial.

Khurram Parvez, a prominent human rights activist, was arrested in November 2021 under the UAPA. His detention drew international criticism, with concerns that the law was being misused to suppress legitimate human rights work.

Asif Sultan, a journalist, was detained in August 2018 under the UAPA for allegedly supporting militant groups. Although granted bail in April 2022, he was re-arrested under the Public Safety Act, resulting in more than five years of imprisonment without a conviction.

Fahad Shah, editor of The Kashmir Walla, was arrested in February 2022 under the UAPA for his reporting. He faced multiple arrests and detentions, spending approximately 21 months in jail before being released in November 2023.

To understand the circumstances leading to Rashid’s imprisonment, one must rewind to May 30, 2017, when the National Investigation Agency (NIA) registered a case under Section 120B of the Indian Penal Code (criminal conspiracy) and the UAPA. The original accused included Lashkar-e-Taiba founder Hafiz Saeed and other secessionist leaders allegedly involved in raising funds through hawala channels to finance terrorist activities in Jammu and Kashmir. Rashid’s name did not figure in the case at the time. He was absent from both the initial charge sheet filed on January 18, 2018, and the supplementary charge sheet of January 22, 2019.

“Engineer Rashid’s case is not an outlier, but a case study in how India’s legal architecture—particularly the UAPA—has, in its zeal to protect “national security”, turned preventive detention into a permanent condition.”

On August 9, 2019—just days after the abrogation of Article 370—Rashid was arrested amid a sweeping crackdown on Kashmiri political leadership. His formal inclusion in the case came later, when the NIA, in a striking act of prosecutorial improvisation, named him in the second supplementary charge sheet on October 4, 2019, alongside four others.

Today, Rashid stands as a stark illustration of the legal machinery in motion—a sitting Member of Parliament who has taken the oath in the House but cannot raise questions; who has won an election but remains behind bars. His case, like many others, reveals how under laws such as the UAPA, detention can function as punishment in itself—requiring not conviction, only accusation.

The UAPA, enacted in 1967 to target activities threatening the “sovereignty and integrity of India”, has grown more draconian with each amendment—in 2004, 2008, and most ominously, in 2019. With every expansion, the law has further blurred the line between the accused and the condemned.

What makes the UAPA truly alarming is its inversion of judicial principles: it shifts the burden of proof, rendering bail almost illusory. Section 43D(5) of the Act allows courts to deny bail if the accusations appear prima facie true. The catch? This threshold requires no substantial evidence—merely a prosecution claim that the allegations seem credible. In effect, the accused must prove their innocence even before the trial begins. It is a legal sleight of hand where punishment precedes verdict, and trial—if it ever occurs—is an afterthought.

Unsurprisingly, the UAPA has been applied most zealously in Jammu and Kashmir, where democracy often takes coercive forms. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, nearly 37 per cent of all UAPA cases in India in 2022 were registered in Jammu and Kashmir. Yet, the conviction rate stood at a mere 3 per cent. This is not the mark of a law targeting real threats—it is the signature of a law wielded to wear people down into silence.

Denying bail, dubious charges

But let us look a little closer at Rashid’s case. What, exactly, are the accusations against him?

According to the NIA, Rashid was not merely a politician but a covert actor working to “legitimise” the United Jihad Council, an umbrella group of militant outfits in Jammu and Kashmir. He allegedly used public platforms to propagate separatist ideology and maintained links with terrorist organisations. The evidence? An email. One Khawaja Manzoor Ahmed Chishti reportedly wrote to Yasin Malik, instructing that a package be handed over to “Shaikh Rasheed Sahib”. Chishti was never arrested—an omission Rashid’s defence team has noted. Then there is the matter of money. The NIA claims Rashid secured funds through the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, with cash couriers discreetly delivering the money for “anti-national activities”. A witness—years after the fact—recalled seeing hawala operator Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali hand Rashid an envelope between 2011 and 2014. Contents unspecified. Intentions presumed. Recollections retrospective. Inferences circumstantial.

Now, a brief detour—Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali. The name may ring a bell. He was at the centre of the 2019 Supreme Court judgment in NIA v. Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali, which turned the idea of bail under the UAPA into a near impossibility. The Supreme Court overturned a Delhi High Court ruling and held that bail could only be granted if the court was fully convinced that the allegations against the accused were not prima facie true. In effect, this shifted the burden onto the accused to disprove the charges—without the benefit of a trial. The judgment cemented the UAPA’s true power: not in securing convictions, but in enforcing prolonged incarceration.

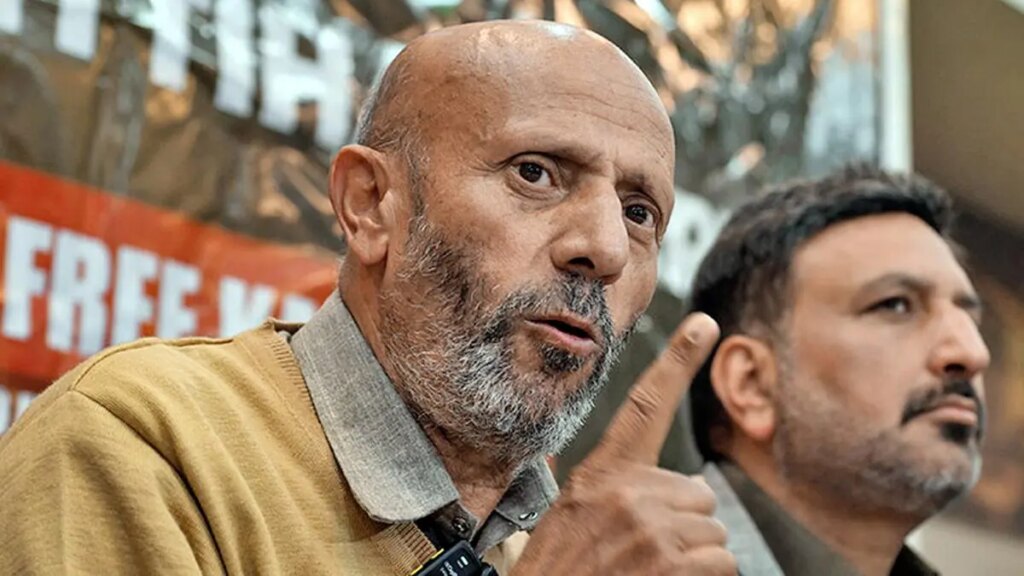

Engineer Rashid addressing a rally in Baramulla district on September 12, 2024. Few victories lay bare the contradictions of Indian democracy as starkly as Rashid’s.

| Photo Credit:

IMRAN NISSAR

Another charge against Rashid? A Facebook post. The NIA pointed to a social media statement in which he allegedly defended Hafiz Saeed, saying that while one might disagree with Saeed’s politics and methods, he was ultimately pursuing a political rather than a global Islamist agenda. A nuanced view, perhaps—but nuance has never been the UAPA’s strong suit. Then came the question of association. The NIA alleged that Rashid shared a “close relationship” with Watali, said to be a financial conduit between Pakistan and Kashmiri separatists. This claim relied on statements from two protected witnesses, one of whom suggested that Rashid, during his tenure as an MLA (2008–18), was used by Watali to further unlawful activities. How, exactly? That remains unclear.

Rashid maintains that the NIA’s case against him rests on a dated Facebook post and the statements of two protected witnesses. As for the email referencing “Shaikh Rasheed Sahib”, he insists it did not refer to him. More significantly, he has already been discharged from charges under Sections 20, 38, and 39 of the UAPA—provisions related to membership of, and support for, a terrorist organisation. He has also challenged the legality of his arrest, arguing that he was never provided with written grounds for his detention.

Kashmir’s favourite law

In Kashmir—where the State sees resistance in every murmur and subversion in every sigh—the UAPA has become routine, embedded in the very fabric of governance. And if a sitting MP, elected with an overwhelming mandate, struggles to secure bail, what hope remains for ordinary Kashmiris? Rashid’s imprisonment is not only about alleged terror funding—charges that were absent from the original charge sheets—but about sending a message: elections may be conducted, but power resides elsewhere. The ballot box may open, but the prison door stays shut.

The misuse of the UAPA has only intensified. Critics, journalists, students, even comedians—anyone voicing dissent—now risk falling afoul of this law. It is no longer confined to enemies of the state; it manufactures enemies where none exist. A bureaucratic guillotine that halts dissent at the indictment stage.

Incarceration under the UAPA is not merely a deprivation of liberty; it is a methodically deployed political weapon. In Kashmir, where the arrests of political figures have long signalled both repression and strategy, Rashid’s prolonged detention has served two purposes: it has galvanised his supporters while simultaneously allowing the State to manage the terms of electoral engagement.

The arrest: An orchestrated duality

For Rashid’s supporters, his imprisonment was more than a legal predicament—it became a lasting metaphor for Kashmiri political subjugation. His sons, Abrar and Asrar Rashid, led his 2024 Lok Sabha campaign, foregrounding his prolonged detention as a symbol of resilience and injustice. The narrative struck a chord with voters, casting Rashid as a committed advocate for Kashmiri rights, silenced not by due process but by political design. His incarceration lent him an aura of authenticity. He was not just another politician seeking office; he was a man whose body bore the imprint of state repression—a leader deemed too dangerous to be free.

This perception energised a segment of the electorate, particularly those who viewed his continued imprisonment as emblematic of the broader suppression of Kashmiri political agency. His campaign, steered by his sons, became an exercise in making his carceral condition hyper-visible. In a sense, the prison cell replaced the campaign stage. His absence became his most compelling presence.

Abrar Rashid, son of Engineer Rashid, addressing an election rally on behalf of his father in the Soibug area of the Baramulla Lok Sabha constituency on May 16, 2024.

| Photo Credit:

NISSAR AHMAD

Yet if incarceration conferred moral authority on Rashid, it also served the State’s interests in ways too strategic to overlook. The Central government’s approach to electoral politics in Kashmir has long rested on regulating participation—permitting just enough space for disruption, but never for consolidation. Figures like Rashid are often allowed to operate within a narrow corridor: enough freedom to stir the pot, but not enough to overturn it.

The Awami Ittehad Party (AIP), founded by Rashid in 2013, was fielded in multiple constituencies during the 2024 election, prompting speculation that the party—wittingly or otherwise—was being used to fragment the anti-BJP vote. With traditional players like the National Conference and the Peoples’ Democratic Party already weakened post-Article 370, a relatively unchecked formation like the AIP risked further splintering the opposition, ensuring no singular Kashmiri voice emerged dominant. Kashmiris, politically astute as ever, recognised the design.

Thus, the state constructed a paradox: a political prisoner whose presence was simultaneously amplified and contained. His imprisonment was instrumentalised by both sides—by his supporters as a mark of legitimacy, and by the state as a tool of electoral engineering.

Also Read | Engineer Rashid’s defiant victory a turning point for Kashmir’s democratic future

Ultimately, Rashid’s incarceration tells a story far bigger than the man himself. Between the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019 and December 2024, more than 2,300 Kashmiris were arrested under terrorism-related charges. Nationally, between 2015 and 2020, of the 8,371 people arrested under the UAPA, only 235 were convicted—a conviction rate of barely 2.8 per cent. But conviction is hardly the point. The genius of the UAPA lies not in establishing guilt, but in enabling punishment without trial. It is a law in which due process is not merely delayed but fundamentally denied; where innocence is incidental, and where accusation itself becomes a sentence.

Few victories lay bare the contradictions of Indian democracy as starkly as Rashid’s. His case is not an outlier, but a case study in how India’s legal architecture—particularly the UAPA—has, in its zeal to protect “national security”, turned preventive detention into a permanent condition.

If democracy in Kashmir is guarded by two locks—one, the spectacle of the ballot box; the other, the silence of the prison cell—then it must be asked: which one truly holds the key to power?

Peerzada Raouf is an assistant professor at O P Jindal Global University. He is currently researching the political economy of carcerality.

Samyuktha Kannan is a student of law at Jindal Global Law School. She researches and writes on carcerality and anti-terror legislations. She is currently working on a project on internet shutdowns in Kashmir.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/politics/uapa-kashmir-engineer-rashid-detention-article-370-democracy/article69385611.ece