On March 9, Tamil social media was awash with messages, audio clips, short videos, and personal testimonies from devoted fans: the verdict was out—Ilaiyaraaja’s first public symphony performance, in London, was a thunderous success. Throughout the day, WhatsApp groups were flooded with congratulatory messages from delirious fans, and it became clear that this was a watershed moment not only for the creator but for millions of his fans who had eagerly awaited this event. After all, this was also a promise kept (more on that later).

When the maestro, fondly called Raja by legions of fans, took to X in May, 2024, to announce that he had composed a full-fledged pure symphony in a matter of 35 days, his aficionados were overjoyed, not only because of the imminent musical feast that awaited them but also because their idol was back to doing what he does best—enthral and enchant followers through his musical explorations. For quite some time before this, Raja had become a polarising figure in Tamil Nadu, earning the ire of millions of his fans by stepping into one controversy or the other, most notably his endorsement of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, with many of his fans refusing to separate the musical from the political.

For fans of a certain vintage, the symphony also brought back bittersweet memories of his first such announcement in the early 1990s. Then too, he made a pilgrimage to London and returned to much fanfare, with everyone eagerly awaiting the commercial release of a symphony. Days turned into months and years but there was no sign of the treat.

Later, it became common knowledge that Raja, for reasons best known to him, had done the musical version of “pulping” a book: he had collected all available tapes of the symphony’s recording and stashed them away somewhere safe. No one knows why, and unless he reveals the reason, it would be impolite to guess.

After an agonising wait of more than three decades, Raja’s fans can now heave a sigh of joy that their icon’s symphony, albeit a new one, has come to fruition with no less an orchestra than the esteemed London Royal Philharmonic (RPO). The RPO website hailed Valiant as a “groundbreaking milestone in global music history”. It also said: “This momentous achievement highlights Ilaiyaraaja’s unparalleled artistry and cements his legacy as a trailblazer across cultures and genres.”

Also Read | A cultural crossover

When a beaming Raja received a standing ovation, it was a triumphant moment for him and also everyone who had supported him in his musical endeavours through the years, cinematic and otherwise.

And when he himself sang Idhayam Poguthe (from the 1979 Tamil film Puthiya Vaarpugal), supported by the orchestra, during a crowd engagement coda when several acclaimed pieces from his cinematic oeuvre were performed, it was a reminder that Raja’s romance with the Western classical genre had begun much earlier than imagined. In fact, despite his dalliances with various musical styles, be it rock’n’roll or disco, baila or Hindustani, Raja has always been faithful to his Carnatic and Western classical moorings.

Mozart in ‘Veettukku’

As early as 1977, a year after a sensational debut in Annakkili, he was already displaying a felicity to introduce Western classical arrangements in the preludes and interludes of his songs, notably in the scintillating Senthoora Poove (16 Vayathinile), which fetched S. Janaki the national award for best female singer. Strangely enough, Raja himself did not receive a national award or nationwide acclaim for the remarkable soundtrack, where he demonstrated that the fusion between Tamil folk music and Western classical could be a match made in heaven. (He would later go on to do this in greater depth in films such as Mudhal Mariyadhai, Kadalora Kavithaigal, and Thevar Magan.)

In 1977 he introduced Western classical arrangements to the preludes and interludes of his songs, notably in the scintillating Senthoora Poove (16 Vayathinile).

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Over the next three years it became evident that Raja’s penchant for Western-style arrangements was here to stay, accompanied by his singular theme tracks in films as well as richly-conceived background scores. One can confidently assert that Tamil film music fans, who had until then not bothered to look beyond songs, began to cherish the beauty of background music, popularly known as BGM, only after Raja’s arrival. Raja had quietly played a key role in edifying the average music listener and elevating the audience’s standards of musical discernment through his innovations; he was, in fact, moulding their musical sensibilities. Unconsciously, they had acquired the ability to appreciate his sophisticated musical explorations, which became more frequent in the 1980s.

Around the same time, he began placing Easter eggs every now and then in his songs, sometimes in the unlikeliest of films, by incorporating pieces by Western masters in a way that was palatable to the lay listener. Thanks to the Internet explosion and diligent excavation by devoted fans, we now know that Dvorak came to us as Chittu Kuruvi (Chinna Veedu), Antonio Ruiz-Pipo was refashioned as Entha Poovilum (Murattu Kaalai), Rimsky-Korsakov was introduced to us in Chittukku (Nallavanukku Nallavan), Mozart in Veettukku (Kizhakku Vaasal), and Georges Bizet in ABC Nee Vaasi (Oru Kaidhiyin Diary).

Also Read | The Carnatic wars

This was his way of paying tribute to those who had influenced him but he continues to be accused of “lifting” from the West. His critics call it plagiarism; his fans call it inspiration.

Crossing oceans

Raja’s first major non-film excursion was the 1986 album How To Name It, a fusion of Carnatic and Western classical that was meant as a tribute to Tyagaraja, the venerable Carnatic icon, and J.S. Bach, one of the greatest names in Western classical. It remains a memorable outing that familiarised his fans with concepts such as the fugue, even though the entire album had distinct Carnatic overtones.

He topped it two years later with another fusion album, Nothing But Wind, which was a jambalaya of Hindustani flute (by the renowned Hariprasad Chaurasia), violin solos, and synthesiser sonatas. Emboldened by the success of these albums, and perhaps realising that it was time for him to move on to the next big thing, Raja decided to try his hand at a full-fledged, pure symphony in 1993. Unfortunately, it did not catapult him into international stardom as was widely expected, which rankles among millions of his fans who firmly believe that he belongs in the global pantheon of musical icons.

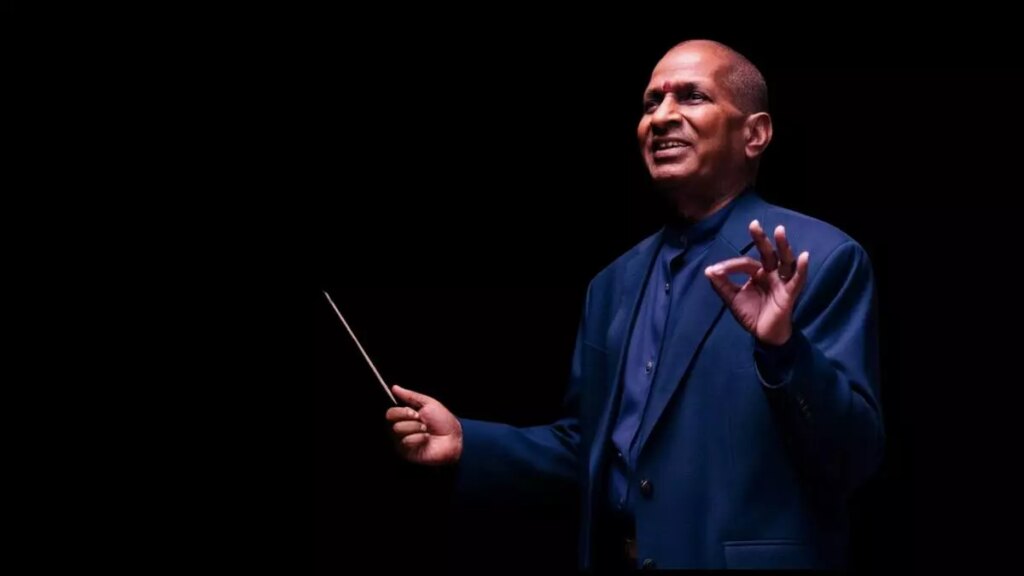

Ilaiyaraaja waves to the gathering as he returns from his Symphony performance in London. Chennai, March 10.

| Photo Credit:

ANI

In 2005, an inspired Raja decided to set a selection of ancient Tamil Saivite hymns to music, and Thiruvasakam in Symphony was born. An oratorio composed and orchestrated by him, it also featured lyrics in English by American lyricist Stephen Schwartz and was performed by the Budapest Symphony Orchestra. Although a seminal album, its reach did not extend beyond Tamil shores. (An oratorio is a composition containing dramatic or narrative text for choir, soloists, and orchestra or other ensemble.)

Since the 1960s, several Indian artists have travelled overseas and established their musical ideologies, cultivating a faithful audience along the way. But they mostly belong to the Carnatic or Hindustani schools of thought. Very rarely do we see someone cross the ocean and set the Western stage on fire by speaking its own musical language. (Maya Neelakantan, a 10-year-old guitar prodigy from Chennai, comes to mind. In 2024, she stormed the US by unleashing a two-minute heavy metal solo at the America’s Got Talent audition. Watch it here.

Raja has always lacked the marketing chops to successfully export himself. He has been immersed in the process of making music through his career. So, it is particularly heartening to see him finally get global acclaim. Perhaps Valiant will usher in an age of global interest in his music.

Music, a third language?

Even today, many themes, preludes, interludes, and BGM bits that bear Raja’s signature are imprinted in the collective consciousness of the community of Tamil music lovers. Although examples are too many to mention, the songs and BGMs of (in no particular order) Aboorva Sagotharargal, Punnagai Mannan, Thalapathi, Aan Paavam, and Raja Paarvai would be a good place to start.

In south India, the musical landscape has changed beyond recognition since Raja’s heyday, but his greatest hits continue to be in circulation and his less-known and even obscure melodies enjoy sporadic bursts of popularity, much of which depends on the whims of social media. His legacy continues to enchant older fans and captivate a new generation just discovering his genius through YouTube and FM radio. The mandatory obeisance paid by budding music directors periodically sends a forgotten song skyrocketing, most recently witnessed in last year’s sleeper hit Lubber Pandhu. Every day there are fresh converts to the religion. The explosion in Internet surfing has also resulted in fans digging deep into his vast oeuvre to engage in some delightful decoding.

The mandatory obeisance paid by budding music directors periodically sends a forgotten song skyrocketing, most recently witnessed in last year’s sleeper hit Lubber Pandhu.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

In what other ways can a society indebted to the legend express its gratitude? For starters, we could, and should, boost interest in Western classical music. Chennai has a long legacy of Western classical and choir music, thanks to the colonial influence (Chennai historian V. Sriram elaborates on this fascinating chapter of the city’s history in this YouTube episode.)

It’s the ideal moment to use Raja’s symphony as a springboard to generate greater interest in the genre, first in the city that made him and then across the State.

The powers that be could also consider including elementary lessons in music at the school level. Western classical has long been seen as alien and it is high time we demolished that notion and embraced the genre as our own, just as China, South Korea, Japan, and Singapore have done. For starters, the Centre could stop insisting on the three-language formula and instead let the State include music in lieu of a third language. After all, what can be a sweeter language?

Finally, Raja’s achievements in scaling various musical summits must get the academic recognition they deserve. His music, one hopes, will become the subject of some serious study in the foreseeable future. The least we can do is take a few steps in the direction where he has taken giant leaps forward.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/ilaiyaraaja-return-valiant-symphony-london-triumph-after-controversy/article69320033.ece