To call a film “brave” is a fragile compliment, because it is not as much about the film itself as about the context in which the film was made and released—“hand on the primal bone/… taking the word from the stream/ Fighting the sand for speech, fighting the stone”, as the poet Dom Moraes said. To call a film “brave” is to demand a society where such words need not be used—the act of this film being exceptional is in the hope that one day such films might be unexceptional. To call a film “brave” is to foreground the weak threshold of gumption in society, and to then gesture at the film hovering stratospherically over it. To call a film “brave” is to mourn a world where such bravery is needed in the first place.

If text and context—what you are saying and which environment you are saying it in—are different beasts, then one of the abiding facts of life under fascist gunpowder can be the collapse of text and context, where bravery becomes the text’s central organising aesthetic and political force. Bravery is not a “formal” property of the text; bravery becomes a formal property of the text—the bridge between those two statements is lapsed freedom.

Telling reaction

As Kunal Kamra’s comedy special Naya Bharat landed him in hot soup, with the Eknath Shinde faction of the Shiv Sena vandalising the venue and Kamra insisting that he would not kowtow to their hooliganism and apologise, the text was pulverised, elevated, honed, burnished, and held aloft by the context. If the French essayist Roland Barthes argued for the “death of the artist”, where we do not mine meaning from the intention and biography of the artist, Kamra’s show produced not just the foregrounding, but also the grounding of the artist in the text.

Also Read | Ukraine’s truth is in the present tense

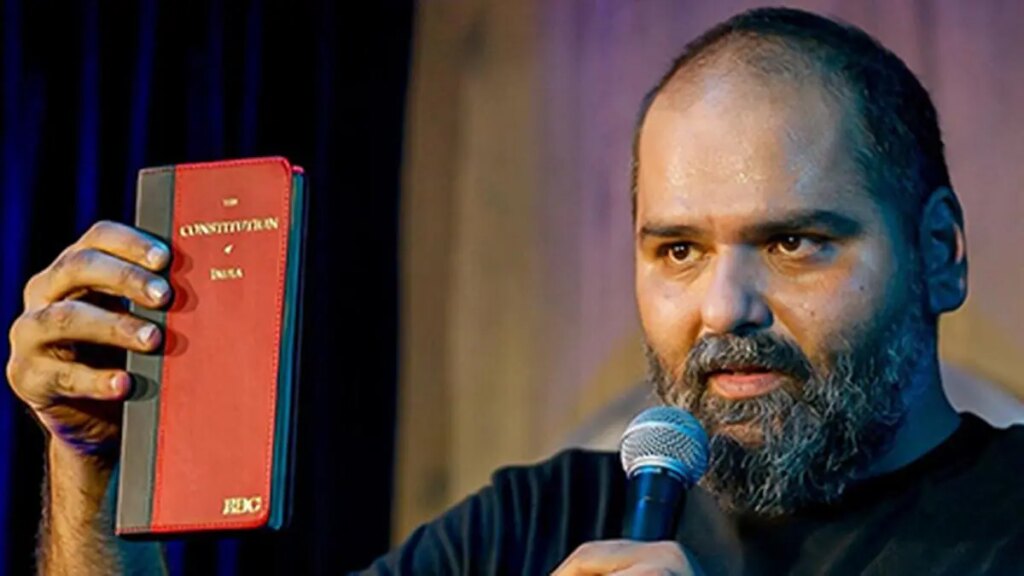

This is not to say that the art of stand-up is itself rendered to the background, but that art is sublimated into the artist in a complicated move. In Kamra’s Naya Bharat and his reaction to its aftermath, his art is the manifestation of the world he is making it in. To be moved by the show—especially towards the end when he whips out the Constitution as an insurance policy against possible violence—is to be moved by its mere presence. It sounds weak, but to have an emotional reaction to a joke is to see how satire has shamelessly fulfilled its purpose—to be. Against all odds.

Kamra’s pinpricking

Kamra is not particularly rip-roaring. That is not his style of comedy either. It is a monotone, stuck somewhere between being bored and amused by life, rendered conversationally. But his pinpricking has often deflated far too many egos, landing him on a no-fly list, for example, of five Indian carriers—making him the first Indian comic, and the third Indian ever to face such a ban—for heckling Arnab Goswami on video on a flight. On his YouTube channel, he hosts films that the mainstream has been afraid of—for example, Anand Patwardhan’s Reason, which was denied permission to be screened by the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, till the Kerala High Court squashed the order.

Kamra’s jokes are not in service of their punchline, because the mere telling of his joke is the punchline. The fact that he can speak of the Ambanis, Narendra Modi, Amit Shah, Eknath Shinde, and Nirmala Sitharaman obliquely or directly or oblique-directly is the joke. Audacity, a genre demand for stand-up, is taken to its logical extreme by putting Kamra’s future on the line—will he be able to perform in Maharashtra again?

Videograb showing Shiv Sena workers vandalising the venue of Kunal Kamra’s show in Mumbai‘s Khar area on March 23.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Watching the comedy special, before it blew up, one was keenly aware of being in the presence of a powder keg. Kamra too had that knowledge, and despite that he kept digging, kept laughing, watching the political establishment from the future fling dirt on him. That way, the spectatorship was twisted beyond the simple act of presence. Spectatorship is now suspended between presence and foreshadowing, between enjoying the now and fearing the later. This suspension, this inability to be present, too, is a gift of fascism.

What is often forgotten about this genre of bravery is the exhaustion that allows its anger to be released. The screenwriter and lyricist Abbas Tyrewala, commenting on the special, wrote: “Did no one else get the fact that he didn’t particularly care about being funny? He was simply picking a fight because he’s f***ing had it.”

Logic of freedom

The strategies that Kamra uses in his stand-up are twofold—and the problem with the strategies is that they are logical, and he thinks logic is a loophole that he can squeeze through in a legal system that privileges power over justice, parody over truth. One strategy is when he does not name the punchline of his joke, but points to it in heavy, evident tones that, in a court of law, will not be admissible as guilt.

Also Read | Chhaava and the mythology of anger

When Aaditya Thackeray of the Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray faction of the Shiv Sena asked Eknath Shinde “Mirchi kyun lagi?” (Why are you so provoked?) when Shinde was not named in the set is an example. The punchline, not Kamra’s speech, was meant to be puzzled into shape in your mind, Aaditya Thackeray noted. As Kamra said in the show, “If you understood this joke, you won’t be angry, and if you are angry, you can’t file an FIR.” The punchline folds itself into another layer and another punchline—if you are a fascist, you are dumb.

To aid this alluding, Kamra used words that have already been levelled at the butt of the joke. As Kamra said in his non-apology after the ruckus: “What I said”—the word gaddar or traitor—“is exactly what Mr Ajit Pawar (first Deputy Chief Minister) said about Mr Eknath Shinde (second Deputy Chief Minister).” The underlying logic—if Ajit Pawar is not being punished for it, why should I—is both valid and stupid. Politics dances on the borderline between farce and fact.

Kamra ended his show by raising a copy of the Constitution, flashing its logic of freedom. But the Constitution is a top-down document: its tenets did not entirely seep into the society it was trying to structure, and this freedom is theoretical. As we have seen in the comments by Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis, when he speaks of freedom of speech what he really means is the freedom of comfortable speech. That your freedom of speech is not accompanied by freedom after speech and that this freedom is not really freedom. To choke a person and ask him to breathe is not really an act of allowing life, is it?

Prathyush Parasuraman is a writer and critic who writes across publications, both print and online.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/columns/kunal-kamra-naya-bharat-shinde-constitution-comedy-vandalise-controversy/article69372668.ece