Dear reader,

Let me tell you about the most remarkable literary long-distance relationship I have encountered in my reading life.

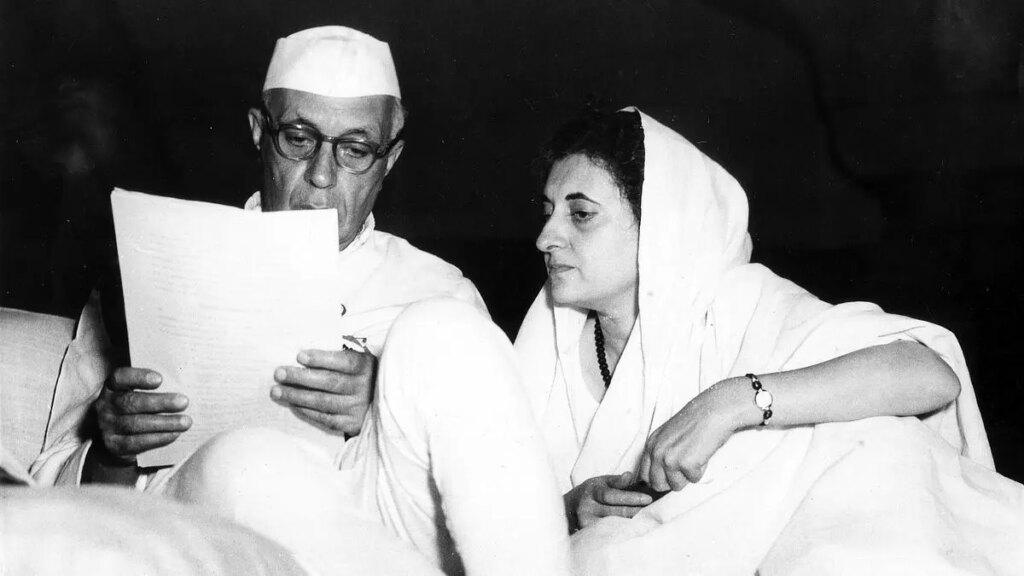

Imagine being a political prisoner and thinking, “You know what would make this incarceration bearable? Writing 196 letters to my 12-year-old daughter explaining the entire history of human civilisation.” That is exactly what Jawaharlal Nehru did while imprisoned by the British in the early 1930s, creating what would become a book I have always admired for its grandeur, simplicity, intellectual richness, and sheer elegance.

You have guessed right: I am talking about Glimpses of World History.

I first read this book during what I like to call my pretentious reading phase in my teens (which, let us be honest, never really ended). What I expected was a dry historical tome. What I got instead was literary parenting so rich and deep that it makes our conventional approaches to teaching history seem lacking in vision.

The book became my unlikely spiritual companion through the chaotic years that followed—a relationship that bordered on the embarrassingly intimate. I would return to it during college all-nighters, career crises, and all that jazz. Each time, like some literary version of those 3D Magic Eye posters from the 1990s, new patterns would emerge that I had somehow missed before.

But the greatest plot twist in my relationship with Glimpses arrived when I became a father myself. Suddenly, passages I had earlier appreciated for their historical insight became an instruction manual for parenting that I never requested but desperately needed. It was as if Nehru had somehow anticipated my future struggles explaining to a toddler why we cannot have ice cream for breakfast and left coded messages across time.

Which is why I thought about the book this past week, when the world was busy chatting about the Netflix psychological drama Adolescence.

As a father to two boys—one in his teens (pray for me)—I especially appreciate the extraordinary nature of Nehru’s parental devotion. To me, his letters represent perhaps the most ambitious act of parenting-from-afar ever documented. Most parents struggle to maintain a meaningful connection during brief separations; I can barely manage a coherent text message from the grocery store. Meanwhile, Nehru built an entire educational framework while imprisoned—a fact that always awed me.

On his daughter’s birthday, unable to give material gifts, Nehru wrote: “What present can I send you from Naini Prison? My presents cannot be very material or solid. They can only be of the air and of the mind and spirit, such as a good fairy might have bestowed on you—things that even the high walls of prison cannot stop.”

Any parent who understands that our most valuable gifts to our children are not material possessions but perspective, knowledge, and wisdom—gifts that transcend physical boundaries and temporal limitations—would connect with the thought here. Though I am pretty sure my son would still prefer the latest PlayStation over my reflections on the Industrial Revolution.

What makes Nehru’s approach to parenting remarkable is his refusal to talk down to his daughter. He treats her not as a child to be protected from complexity but as a developing mind eager to engage with the world’s biggest questions. “It is a good habit to read books,” he writes, “but I rather suspect those who read too many books quickly. I suspect them of not reading them properly at all, of just skimming through them, and forgetting them the day after.” I would not blame you if you felt this was written for today’s social media, information-deluge age.

Indeed, it feels like a direct critique of our age’s skim-an-article-and-pretend-expertise technique that many of us have perfected over the years.

For parents of teenage children wrestling with today’s information-saturated world, Nehru offers a model of engagement that respects young people’s intelligence while providing crucial context. Rather than shielding his daughter from difficult truths, he equipped her to understand and confront them. (It is a historical irony that the very circumstances that shaped Indira Gandhi’s life and career forced her onto a trajectory that collided with the ideals she was brought up with; I am referring to the Emergency.)

In an age when your teenage son is bombarded with information but often starved for wisdom, Glimpses of World History offers a model of education that goes beyond facts to provide perspective. Nehru does not merely teach history; he demonstrates how to think historically—to see patterns, make connections, and understand present challenges in the context of humanity’s ongoing story.

When teenagers have unprecedented access to knowledge but often lack the context to interpret it wisely, Nehru’s focus on transparency feels particularly relevant. He advises: “Even so in our private lives let us make friends with the sun and work in the light and do nothing secretly or furtively. Privacy, of course, we may have and should have, but that is a very different thing from secrecy.”

This distinction between privacy and secrecy offers valuable guidance for parents raising teenagers in the digital age—including this writer. Our children deserve privacy as they develop their identities, but secrecy—a culture of concealment and shame—creates barriers to the honest communication that builds trust.

For parents raising children in a rapidly changing technological world, Nehru’s approach to teaching science offers further insights. He does not merely present scientific facts but stresses the process of inquiry and the evolving nature of knowledge. “Remember that human thought is ever advancing,” he writes, “ever grappling with and trying to understand the problems of Nature and the universe, and what I tell you today may be wholly insufficient and out-of-date tomorrow.”

This humble acknowledgement that knowledge is provisional models intellectual humility for young minds often bombarded with certainties. Nehru’s passion for science shines through: “Science… helps us to understand life, and thus enables us, if we will but take advantage of it, to live a better life, directed to a purpose worth having. It illumines the dark corners of life and makes us face reality, instead of the vague confusion of unreason.”

This sense of wonder about the natural world is a gift any parent can share with their children, regardless of scientific background or ability to remember basic chemistry from high school (ahem).

At a time when young people are staring at an increasingly polarised world, Nehru’s thoughts on communal conflict offer further clarity. He acknowledges the reality of division while reaffirming unity: “Today, sometimes, there is communal conflict in India, and Hindus and Muslims fight each other… It is a shameful thing for any Hindu or Muslim to fight his brother in the name of religion.”

His insistence that “our real interests are one” challenges the zero-sum thinking that dominates many contemporary crises in the country. For parents helping teenagers develop their moral compass in a world of competing ideologies, this approach offers a useful guide to acknowledging difference while affirming our shared humanity.

As your children grow into a world of increasing economic inequality, Nehru’s analysis of economic systems in Glimpses of World History becomes especially relevant. He explains how science and industrial capacity have outpaced our economic models: “Science and industrial progress have gone far ahead of the existing system of society. They produce enormous quantities of food and the good things of life, and capitalism does not know what to do with them.”

His critique of “The doctrine of cut-throat competition between individuals and nations, and the devil take the hindmost! … Capitalism had nothing to do with religion or morality” feels startlingly modern.

In our age of broken attention spans and disposable content, Nehru’s sustained act of paternal love—taking the time to craft thoughtful, nuanced explanations of human history—feels almost radical. What I admire most is his intellectual honesty, telling his daughter: “You must not take what I have written in these letters as the final authority… My likes and dislikes are pretty obvious… I do not want you to take all this for granted.”

As I handhold my own sons through the complexities of the digital age, I find myself returning to Nehru’s simple acknowledgment of the limitations of even his most ambitious educational efforts: “I have written a very long letter to you. And yet there is so much I would like to tell you. How can a letter contain it?”

In this humble admission lies perhaps his greatest parenting wisdom: we can never transmit everything we wish to share, but we must try nonetheless, offering our children not just information but frameworks for making meaning in an increasingly chaotic world.

Reading Glimpses in 2025 feels as if Nehru had a crystal ball. His observations on nationalism, propaganda, economic inequality, and the dangers of misinformation read as though he spent a weekend scrolling through our social media feeds before writing.

In all seriousness, Glimpses of World History offers something increasingly precious: a thoughtful guide to making sense of human experience across time and cultures. Written by a father to his daughter, it reminds us that understanding our past is not merely an academic exercise but an act of love, preparing future generations to create a better world than the one we have handed them.

And is that not what Gen Z, beneath all the memes and digital anxieties, is really looking for? Not just information, but wisdom. Not just facts, but meaning. Not just content, but connection. Nehru’s letters to his daughter offer all of these, wrapped in the most ambitious history lesson ever conceived by parental love.

And that is one of the many reasons why I feel Jawaharlal Nehru continues to be relevant even today—and why I miss him. I belong to a generation that knew him only through stories told by our elders, but fortunately, there are still many in the country who were lucky enough to have met this legend.

P. Krishna Gopinath is one of them. The latest edition of Frontline carries a wonderful first-hand piece by him titled “Nehru comes to town”, in which he recounts his encounter with the country’s first Prime Minister and the impact it had on him. It is a delightful read.

Do read it and share your thoughts—and your criticisms—about Nehru, his writing, his life and his legacy.

Jinoy Jose P.

Digital Editor, Frontline

We hope you’ve been enjoying our newsletters featuring a selection of articles that we believe will be of interest to a cross-section of our readers. Tell us if you like what you read. And also, what you don’t like! Mail us at [email protected]

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/newsletter/the-frontline-weekly/jawaharlal-nehru-indira-gandhi-glimpses-of-world-history-parenting/article69456970.ece