“Unfortunately for me I was born a Hindu Untouchable. It was beyond my power to prevent that, but I declare that it is within my power to refuse to live under ignoble and humiliating conditions. I solemnly assure you that I will not die a Hindu,”1 thundered Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar at a conference in Yeola, near Nashik, Maharashtra, on October 13, 1935, marking a decisive break with Hinduism and its oppressive caste structure.

Yet, it took him over two decades to take the final step. During that period, he relentlessly fought against caste discrimination, championed Dalit rights, and rigorously studied various world religions. His search for a faith rooted in equality and human dignity ultimately led him to Buddhism.

Historic decision

On October 14, 1956, in a historic gathering at Deekshabhoomi in Nagpur, Dr Ambedkar, accompanied by 360,000 Mahars, publicly embraced Buddhism in what became one of the largest religious conversions in world history. India had seen religious conversions before, but none matched this moment’s scale and symbolic significance.

On May 30 and 31, 1936, he convened a landmark conference in Dadar, Bombay (now Mumbai), to gauge support for the conversion movement following his influential Yeola declaration. Several Sikh and Muslim leaders, along with religious priests, attended, eager to understand his stance on conversion.

Also Read | Why Ambedkar rejected Gandhi’s idea of Dalit emancipation

The conference aimed to devise strategies for implementing the resolution passed at Yeola. While Dagduji Dolas delivered the welcome address, B.S. Venkatrao, a prominent Dalit leader from Hyderabad, chaired the proceedings. The gathering brought together approximately 35,000 Mahars, providing Dr Ambedkar with a crucial platform to articulate his vision of religious conversion as both a spiritual and material necessity.

To ensure clarity in conveying his message, he meticulously prepared his speech, which serves as the foundation of this essay.2 He argued that conversion should be understood through two key dimensions: the social and religious, and the material and spiritual. He framed his discourse around two fundamental questions: What is the purpose of religion? And why is it necessary?

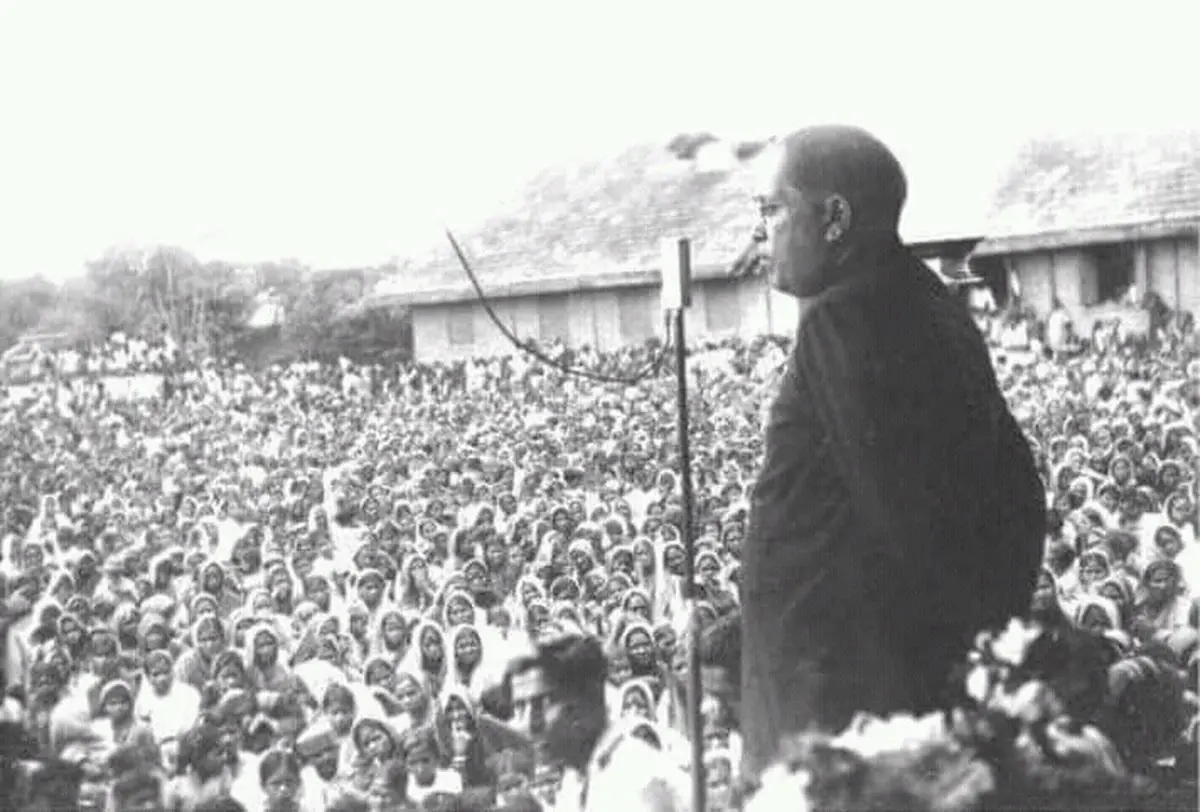

Dr Ambedkar addressing a large crowd of supporters. On May 30 and 31, 1936, he convened a landmark conference in Dadar to gauge support for the conversion movement following his influential Yeola declaration.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

Dr Ambedkar, while agreeing with Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s definition of religion as “that which governs people”, acknowledged its influence in shaping society’s moral foundation. However, he contended that religion could serve as either a vehicle for justice or a tool for oppression. Drawing from various philosophical perspectives on the purpose of society—be it maximising happiness, cultivating human potential, or achieving an ideal order—he maintained that a just society must uphold dignity and equality rather than perpetuate hierarchy.

True religion, he asserted, should empower individuals rather than sustain entrenched power structures. Rejecting the idea that individuals should dissolve into society like a drop in the ocean, he saw religion as a catalyst for liberty, equality, and justice. Given Hinduism’s deeply entrenched caste structure, can it truly function as a vehicle for liberty, equality, and justice?

Hinduism and Dalits

Dr Ambedkar contends that Hinduism systematically divides society into four artificial varnas, rigidly assigning roles and denying the possibility of social mobility, particularly for Dalits, who are positioned outside the varna order. Hindu scriptures, such as the Vedas, Smritis, and Dharmashastras, codify and legitimise this system of graded inequality, imposing harsh penalties on those who defy caste boundaries.

The doctrine of karma further reinforces this structure by attributing an individual’s suffering to past-life actions, thereby discouraging resistance among the oppressed while absolving caste Hindus of accountability for their oppression of and discrimination against Dalits. While other religions, at least in principle, uphold the ideal of universal brotherhood, Dr Ambedkar argues that Hinduism institutionalises social exclusion.

He emphasises that Hinduism’s oppressive ideology extends beyond theological doctrine and deeply shapes the everyday realities of Dalits. Caste Hindu society imposes strict restrictions on Dalits’ mobility, residence, and occupations, perpetuating their subjugation. Dalits are prohibited from entering temples, drawing water from public wells, or accessing roads and public spaces reserved for caste Hindus.

Deemed impure by birth, they are forced to live on the outskirts of villages, which reinforces both their physical isolation and symbolic exclusion from the Hindu social order. Interestingly, this exclusion is not merely spatial but extends to the systemic denial of education and economic opportunities. Dalits are kept away from education and meaningful livelihoods, which confines them to menial labour such as cleaning latrines or disposing of animal carcasses and other forms of manual work that caste Hindus refuse to do.

Dr Ambedkar highlights the consequences that Dalits face when they seek to break free from caste-imposed roles or challenge social norms. Even everyday acts such as wearing a watch, riding a horse, or drinking water from a well can provoke violent retaliation.

A Dalit youth who was attacked by caste Hindus for riding a Bullet motorcycle, on February 12.

| Photo Credit:

BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

A chilling example of this was seen in Tamil Nadu as recently as February 12, 2025, when caste Hindus hacked the hands of a 21-year-old Dalit student from Melapidavur village in Sivaganga district for riding a “Bullet” motorcycle, an act perceived as defying caste restrictions.

Violence against the oppressed

National Crime Records Bureau data show that in 2020, 2021, and 2022, no less than 50,000 cases of violence against Dalits were recorded nationwide each year. These exclusionary practices do not merely marginalise Dalits; they actively dehumanise them, embedding their subjugation in the fabric of caste Hindu society. Such atrocities are not isolated acts but are deeply rooted in religious ideology, which upholds caste purity as essential to maintaining dharma.

Can Hinduism be reformed to dismantle caste and give equality to Dalits? There is an inalienable relationship between Hinduism and its hierarchical social order. One cannot conceive of Hinduism without its caste system. In this sense, belief in Hinduism is inherently belief in caste. This fundamental link is precisely why Ambedkar categorically dismissed the possibility of genuine reform within Hinduism.

He argued that even well-intentioned reformers failed to challenge the core principles of Hinduism that upheld caste. Social reform movements, such as those led by Mahatma Gandhi, sought to eradicate untouchability but not caste itself. As a result, Dalits would continue to do menial jobs and have subordinate positions but be called Harijans.

To highlight the limits of the reform efforts, Dr Ambedkar drew a comparison with white abolitionists in America. While both Black Americans and Dalits suffered systemic oppression, the key difference was that American slavery was legally sanctioned, whereas caste-based oppression in India is sanctioned by religious doctrine.

He observed: “The difference between the two was that the slavery of Negroes [Blacks] had the sanction of the law while your [Dalit] slavery is creation of the religion” (Ambedkar, 2020[1936]:135).

Also Read | Ambedkar and Periyar: On the same page

Dr Ambedkar pointed out that some white Americans genuinely believed slavery was inhuman and were willing to fight against their own brethren. They waged a civil war, shedding their own blood for the abolition of slavery. In contrast, he challenged Hindu reformers with a direct question: “Are you prepared to fight a civil war with your Hindu brethren like the Whites in America…?”

Based on his experience of working with various social reformers, Dr Ambedkar observed that they made superficial adjustments rather than advocating complete dismantling of caste.

The equality question

For Dr Ambedkar, Hinduism inherently denies Dalits the possibility of equality within its caste framework. He illustrated the extremity of caste-based discrimination through examples where Dalit touch is believed to render a person impure, to pollute water, and even desecrate a deity. Rejecting the claims by some Hindus that education, cleanliness, and wealth would lead to equal treatment of Dalits, he argued that even educated and affluent Dalits faced the same social exclusion.

In contrast, Dr Ambedkar (2020:125) emphasised the egalitarian ethos of Islam and Christianity, arguing that true equality “has no concern whatsoever with knowledge, wealth, or dress, which are outward aspects of one’s self”.

He posed two fundamental questions: What value does a religion hold if it denies human dignity? Why should Dalits remain bound to a faith that condemns them to perpetual subjugation, inequality, and mental servitude?

For him, untouchability was not simply individual injustice, but systemic oppression imposed by one class upon another. At its core, caste-based subjugation is about social status—while one class seeks to dominate, the other struggles to resist. How long can this struggle continue?

Dr Ambedkar (2020:118) argues that the struggle between caste Hindus and Dalits is “a permanent phenomenon” as it is embedded in a religious system that presents itself as eternal and unchangeable. Thus, he asserts, caste will persist indefinitely. In this context, a crucial question arises: can Dalits sustain their fight against systemic oppression?

He addressed the dilemma with absolute clarity. Those who are willing to accept a life of servitude, submitting to the dictates of Hindu society, need not wrestle with this question. However, for those who aspire to dignity and equality, serious reflection is necessary.

“In Dr Ambedkar’s view, conversion serves as a powerful act of emancipation: dismantling both social and psychological forms of enslavement, and enabling Dalits to reclaim their agency and self-worth.”

Yet, Dalit resistance is hindered by systemic barriers such as economic deprivation, geographic dispersion, and ingrained psychological oppression. Despite their numerical strength, the geographic dispersion and internal divisions of Dalits hinder any collective mobilisation. The lack of land ownership, stable employment, and legal protection further entrenches their dependence on privileged castes.

More insidiously, centuries of systemic oppression, reinforced by religious dogma and social norms, have inflicted deep psychological scars, perpetuating a sense of resignation and eroding self-confidence. This internalised oppression makes the struggle for dignity even more arduous.

Faced with these entrenched obstacles, Dr Ambedkar argues that Dalits must seek alternative pathways. However, caste-based social morality renders cross-community solidarity elusive: even those who recognise the injustice of untouchability are often passive, constrained by caste and religion. Religious conversion, thus, emerges as a means of dismantling systemic oppression.

Liberation through conversion

For Dr Ambedkar, conversion is not merely a change in faith but a radical act of self-liberation. He contends that as long as Dalits remain within Hinduism, they remain bound by its ideological and institutional frameworks that sustain oppression. Only by severing these ties, embracing a new religious identity, and integrating into an alternative social structure can they access the support, protection, and dignity that have been systematically denied to them.

In Dr Ambedkar’s view, conversion serves as a powerful act of emancipation: dismantling both social and psychological forms of enslavement, and enabling Dalits to reclaim their agency and self-worth. As he emphatically asserts, “Conversion is the only path to eternal bliss” (Ambedkar 2020-143).

Yet, this assertion invites a critical question: does conversion truly liberate Dalits from the caste system?

The question warrants serious consideration, for even after converting—particularly to Christianity, Islam, or Sikhism—Dalits continue to be socially identified as such and remain subject to systemic exclusion and economic marginalisation. In light of this, one must ask: can conversion alone dismantle deeply entrenched caste hierarchies?

The Gidheshwar temple at Gidhagram in West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district, where five Dalits from Daspara offered their prayers for the first time in centuries.

| Photo Credit:

SHRABANA CHATTERJEE

Dr Ambedkar did not ignore the existence of caste in non-Hindu religions, but he drew a sharp distinction between the Hindu social system and those of other religions.

He argued that “if Muslims and Christians start a movement for the abolition of the caste system in their respective religions, their religion would cause no obstruction. Hindus cannot destroy their caste system without destroying their religion” (Bhagawan Das, 1969:51).

Meanwhile, some scholars argue that Dalits can assert equality within Hinduism by reinterpreting its scriptures and challenging traditional practices. In recent years, examples of temple entry movements and Dalits becoming temple priests, an occupation historically reserved for Brahmins, have been cited as both challenges to caste oppression and signs of reform within Hinduism. While these efforts are undoubtedly significant, they fail to fundamentally dismantle the entrenched caste structure. Dalit efforts to enter temples are still consistently met with resistance.

A striking example was the entry of Dalits for the first time into a centuries-old Siva temple at Gidhagram in West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district on March 12, 2025. However, there was a hue and cry from members of the privileged castes, who refused to accept the need for change. The presence of more than 100 police personnel and enormous pressure from the government prevented them from stopping the Dalits’ entry, which was a hard-fought victory.

Relevant vision

Dr Ambedkar’s vision of religious conversion as a means to escape caste-based oppression remains highly relevant in modern India. It is particularly relevant in the context of the new anti-conversion laws, which impose legal and bureaucratic restrictions that undermine Article 25 of the Constitution, which guarantees religious freedom.

These laws disproportionately target marginalised communities, reinforcing Dr Ambedkar’s critique that Hindu society resists any challenge to its caste hierarchy. Although the BJP-led government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi portrays its anti-conversion laws as safeguards against “forced” or “fraudulent” conversions, in practice, the laws curtail the autonomy of Dalits and Adivasis, making religious conversion difficult.

Also Read | Justice Chandru report illustrates eradicating caste in classrooms remains a tall order

One of the most striking examples of structural resistance to Dalit emancipation is the denial of Scheduled Caste (SC) status to Dalits who convert to Islam or Christianity, thereby excluding them from affirmative action policies.

Additionally, ghar wapsi (homecoming) programmes, which seek to pressure Dalit converts into returning to Hinduism, illustrate the continued policing of religious identity.

Dr Ambedkar’s decision to embrace Buddhism was both a personal conviction and an act of defiance against a system that perpetuated oppression. But he too recognised that conversion alone was insufficient—true emancipation required political strength, economic empowerment, and legal safeguards.

Sambaiah Gundimeda is an Associate Professor and Coordinator of the Politics Division at the School of Interwoven Arts and Sciences (SIAS), Krea University, Sri City, Andhra Pradesh.

1 Bhagawan Das (ed.), Thus Spoke Ambedkar: Selected Speeches, vol. 1 (Jalandhar: Bheem Patrika Publications, 1969, page 108).

2 B.R. Ambedkar, “What Way Emancipation?”, in Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, vol. 7. (Bombay: Government of Maharashtra, 2020 [1936], pages 13-147).

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/politics/ambedkar-caste-discrimination-dalit-emancipation-conversion-buddhism-religious-freedom/article69452119.ece