In this wide-ranging conversation, acclaimed Kannada filmmaker Girish Kasaravalli shares his insights on Satyajit Ray’s distinctive cinematic vision with essayist, academic, and translator Chinmoy Guha. From Ray’s “lyrical humanism” and episodic storytelling in Pather Panchali to his evolving political voice across different phases of his career, Kasaravalli talks about how Ray revolutionised Indian cinema by creating a minimalist idiom that transcended regional boundaries while remaining deeply rooted in local realities. The conversation was held as part of an event organised by the Satyajit Ray Film Society, Bengaluru, during Ray’s birth centenary year.

Excerpts:

It’s a great honour to have with us Girish Kasaravalli, one of the legends of post-Ray Indian cinema. I remember my first encounter with him through his film Ghatashraddha (1977) when I was in my second year of MA in Calcutta University. It was a revelation. It was so ruthlessly honest about the ground reality and yet artistically so different from his contemporaries. We shall basically be interested in knowing his views about the films of Satyajit Ray.

Let me begin by citing a letter by Rabindranath Tagore, written on November 26, 1929, to thespian Sisir Bhaduri’s brother Murari Bhaduri: “I think the new art of cinema is yet to grow. The quest for originality is the objective of art, and every artist seeks the freedom of self-expression. Otherwise, its dignity is compromised. Till now, the slavery of cinema to literature has made it undignified; no artist has been able to liberate it from this slavery by his own talent.”

This finally happened when Ray arrived on the scene of Indian cinema. Eric Rhode wrote in the chapter “Internationalism” in his monumental book A History of the Cinema from Its Origin to 1970 that a revitalised Swedish film industry led by Bergman, the emergence of Satyajit Ray as a major director, and the recognition of the Japanese (he meant Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, and Ozu), who “enlarged the perception of cinema” in the 1950s.

Although influenced by Vittorio De Sica’s neo-realism, one thing was clear: Ray’s narrative was different. There was an inner lyricism ‘à la Renoir’ and an incredible sense of structure. Even if it looked realistic on the surface, it operated on various levels and his images were unconventionally creative and cinematic. For the legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ray’s films “had an upsetting beauty”.

There was also a nuanced characterisation, a flurry of echoes and cross-references, a structural harmony reminiscent of Mozart, and impeccable editing. (Ghatak called him the finest editor in the country). Also, it almost seemed like actors such as Subir Banerjee, Soumitra Chattopadhyay, or Sharmila Tagore were born to play those characters in Ray’s films. Like Tapen Chatterjee was born to play the role of the singer in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne.

André Bazin said as early as 1957 that Ray strung the cluster of images in a completely new way, and this left traces in memory. Ray did a kind of humanisation of cinematic discourse in a way that Indian cinema had not witnessed before. Before I move on to Girish, I would like to remind readers that Ray never repeated himself and stubbornly went on exploring the ways of the world, much like Girish himself.

Now, to Girish, one of the pioneers of Indian cinema (I won’t use the term “parallel cinema” but would say “real cinema”). Before you speak, let me tell you that I’ve watched all the films you’ve made over the years.

You were born in Kesalur, Thirthahalli, Shimoga, Mysore State (now Karnataka). You came from a family of freedom fighters and agriculturalists. All this matters. And then you eventually got drawn to the touring talkies and then, one day, you delved deep into the human psyche, and the camera spoke with you; the camera became so eloquent and yet so precise, which is reminiscent of Ray.

So, Girish, you were a budding pharmacist and then enrolled at FTII Pune, where you won a gold medal. What was your first exposure to Ray?

Well, I had heard about Ray even before joining the Film Institute in Pune. In Pune, we used to have screenings of two different films a day, at 5:30 pm and 9:30 pm. The film screened at 5:30 pm used to be a classic, and the one at 9:30 pm would be a contemporary film. I had heard a lot about Ray’s Pather Panchali but could not watch it yet, so I was dying to watch it. Particularly because one of my classmates, after every single screening every day, would say, “No, no! Pather Panchali is far, far superior to this!” He would say the same for every film. Then, finally, one day, when Pather Panchali was screened, I got completely bowled out and I realised why my classmate would call the film superior to any other films we had seen so far. It’s still my favourite Ray film. But before Pather Panchali, I had seen Pratidwandi in Hyderabad, where I had been working as a pharmacist in a company, IDPL. So, that was my first encounter with Ray.

Girish Kasaravalli revisits his first impressions of Pather Panchali, traces Ray’s stylistic innovations, and explores the filmmaker’s influence on the evolution of post-Independence Indian cinema.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Well, Pratidwandi was a very special film in Ray’s oeuvre… one of his most experimental, using techniques Ray never used again. But, Pather Panchali, as you said, still remains your most favourite Ray film. Why?

Well, you mentioned a few minutes ago that Ray was influenced by the neo-realists. Indeed, he was. Yet his way of seeing was quite different and unique. His was a kind of realism coupled with lyricality, a sort of lyrical humanism, if I may so call it. Ray tried to bring in a new kind of minimalistic idiom into cinema, which was quite different from all the filmmakers of the time and even today. Andrew Robinson said, “Ray’s is a kind of art that conceals art”. This is exactly what I liked most about Pather Panchali. And, Ray plays a very significant role in the history of cinema because the kind of films he started making were totally different from the other films being made at that time. In that sense, he heralded a new style, a style which can be found in Pather Panchali, where he did not use any linear narrative. This was something extraordinary at that time.

Pather Panchali is very episodic and also very polyphonic in nature, but the way Ray arranges all these sequences is unique. When Truffaut left the cinema hall, saying Pather Panchali was “full of paddy fields,” it was André Bazin who held him and told him to watch the film again, as Bazin was already moved by the unmanipulated representation of the baffling visuals. And, though Pather Panchali was wrongly compared to the films of Robert J. Flaherty, Ray’s films did not, at all, resemble Flaherty’s. Also, the whole notion of evil, which was not there in Ray’s film, baffled the larger Western audience.

Also Read | Still on the rails: Ray’s Nayak and the restless shadow of a star

This is probably because they were influenced by Western modernism.

Yes, but the film was not, at all, about evil. Ray had rather a holistic approach.

Yes, and I think that’s part of Ray’s humanism. Even the most mischievous or roguish characters in Ray are not evil but rather sad and lonely. Perhaps Ray had a sense of sympathy for all human beings, irrespective of good or evil.

Yes. You know, in literary parlance, there’s something they call the Advaitic way of representation or non-linear representation. Ray did just that. In Ray’s films, all characters are important, even the minor, the peripheral sidekicks, everyone.

“Well, I believe all great artists are critical insiders. While watching a film, an artist, unlike a common man, would question himself, “Am I also not a part of it?” Ray did it too.”Girish Kasaravalli

Yes, even the headmaster in Aparajito or the doctor who comes in to see Durga just for a few moments in Pather Panchali all come alive. They are all painted as complete human beings, even if they appear for a few seconds.

Very often, people say Ray’s political statements are muted. But I don’t agree. I believe politics can be shown in two ways. One way is to look at quotidian life and see the resistance built within the characters. The other way is strongly ideological. You, as the director, take an ideological stance and observe and let everything happen on screen from a vantage point. Ray never does that. Instead, he looks at smaller details with which he constructs a universe. There are many such beautiful “constructs”. If you take any of these scenes away, nothing will happen to the narrative, because, as I said, like in Pather Panchali, Ray’s films are very episodic.

Episodes, if I may say so, are juxtaposed in the form of a montage. In Pather Panchali, there are basically five regular characters, and all are thinking of something positive to happen in their lives. Starting with Pisi, who, with her very poor eyesight, is threading a needle. She hasn’t given up hope. Sarbajaya, the mother, is thinking of her girl Durga getting married into a well-off family. Durga, who has no serious concern in her life yet, keeps wondering if she had two binunis (strands of hair), and then, Harihar, the priest and father, is seen giving Apu, his son, English dictation, and on its being done, Harihar praises Apu. Then the father asks his son to write the spelling of “wealth”. And then, Apu hears a train passing and asks Durga, “Didi, have you ever seen a train… let us go and see the train.” And with this, the scene ends.

What purpose does it serve? It doesn’t serve any purpose in terms of the plot, but it does serve a purpose in terms of its idea. It’s a story of a family which is hoping and striving to make their life meaningful. That’s why I called Pather Panchali “a montage of optimism”. Despite all the odds of life, Ray never makes his characters dispirited. That’s what I like most about Ray and his Pather Panchali. It’s through this optimism that Ray offers his political views. That’s why I said Ray was different from the neo-realists. And, when many say Ray’s films do not have strong political statements, I wonder, isn’t looking at life with all its complexities a political statement? However, in Ghare Baire, Ganashatru, and in the city trilogy, the political statement is even more pronounced.

Through the lens of Apu’s journey, Kasaravalli explores how Satyajit Ray crafted a deeply humanist vision of Indian childhood, loss, and resilience.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Yes, and, I think, in Sadgati too.

Yes. You see, David Robinson used the phrase “the rightness of the images”. Ray had this rightness in his films. The rightness of the images is not only about presenting real situations but also about the humanising spirit that works behind everything. As in Indian music, when the musician plays the sympathetic string juxtaposing it with the other string of the sitar, you get to hear the desired swaras made even richer because of the ambience created; Ray also juxtaposed his images to perfection.

I think the rhythms in Ray’s films and the lyrical quality of his images are very important.

Yes, very much. When Ray was asked if his craft was all about realism and humanism, he said, “There’s more than humanism in my films. Much more is the lyricism of the images instead”. So, the rhythm and the lyricism in Ray are not mere decorative elements, but they are as important as the humanism to drive home the narrative. He uses the lyricism to create the empathy he had for all his characters.

That’s right. So, it’s clear that many have missed the lyrical quality while focusing only on the details and narrative of his films. Now, another thing you said is that Ray imbibed all kinds of influences from Renoir and De Sica and Hollywood. You called Ray a “critical insider”, just like you yourself are. You also gleaned from all sorts of influences in your Ghatashraddha, or Tabarana Kathe, or Gulabi Talkies.

Well, I believe all great artists are critical insiders. While watching a film, an artist, unlike a common man, would question himself, “Am I also not a part of it?” Ray did it too. It happens to almost every artist. An artist, while witnessing someone else’s art, does not merely stand outside and pass comments, but he himself critically immerses empathetically in the work as an insider. And that’s why Ray can make even his own characters so full of life. Like when Durga steals a fruit in Pather Panchali, Sarbajaya scolds and slaps Durga for it, but in the end, we will see Sarbajaya also take a coconut without anyone seeing her. So, these keen observations that Ray makes of human life help us to understand that neither the mother nor the daughter is bad, but rather their life compels them to do the things they are doing. And yet Pather Panchali is a celebration of life. And so is Mahanagar, one of my favourites. It’s one film, I think, that one needs to study in greater detail. It’s very crucial to understand why we empathise with the character of Arati, or how Ray constructs the middle-class milieu and also his construction of mise-en-scène.

Do you think, Girish, that Ray’s mise-en-scène revolutionised the world of cinema? For example, in Mahanagar, Dada and Boudi, Subrata and Arati are busy in an intimate conversation; the young sister comes up and pulls the curtain. These details are, I think, what make Ray’s films so fantastic and stand apart. What do you think?

Yes, absolutely. I think that’s why Pauline Kael, while talking about Ray, says, “His films do not make an impact because of their great performance or story but because you realise you are suddenly part of it.”

Now, I would like to know how you consider the significance of the beauty of quotidian life in Ray’s films. Personally, I have always admired the same in all of your films, but what do you think of Ray in this line?

The quotidian is always very significant in Ray. Ray knew how to bring out the best of the quotidian, how to make it look the most beautiful of all and that’s exactly what he did.

Kasaravalli reflects on how Apu’s world in Pather Panchali embodies Ray’s lyrical realism—where everyday struggles become moments of quiet transcendence.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

I remember Stanley Kauffmann, in an article in The New York Times, wrote that “Ray is so close to his material that every detail seems meaningful”. I think this is so very true for your films, too. By the way, let me just remind our readers of the great films you made, such as Ghatashraddha, Naayi Neralu, Dweepa, and, of course, Ek Ghar in Hindi. Besides, you made great films on Ananthamurthy and Adoor Gopalakrishnan. Another thing, Girish… Ray wrote his own screenplays. Do you think that helped him to conceive things the way he wanted?

Yes. Of course. That is why stories in Ray’s or even in my films are not narrated; they rather unfold or unveil right in front of you. When nobody is telling you the story but the story itself gets unveiled before you, you no longer just watch the film but participate in it. That’s what the case is with my characters Narmada or Nagi and so on.

Another aspect you have repeatedly said about Ray is of his universal vision.

Yes, Ray had the ability to lift a story from a regional socio-political milieu to a universal one. He never chained himself to a particular vision or idea. That’s why you can watch his films anywhere and still relate to them. He knew how to lift the local to the height of the global, universal. But I think this is a quality not specific to Ray but to all great filmmakers. That’s why you see a film by Kurosawa and you can relate to it sitting in India.

So, as I get it, you are basically pointing to Ray’s rootedness. And I think that’s a quality you and Adoor share with Ray. You and Adoor make films in Kannada and Malayalam, and yet reach out to a universe beyond. Of course, you have had the influence of other greats such as Ozu, Antonioni, and Kurosawa on you.

But the multilayered storytelling and the transition to the universal in your films remind me of Ray. And, critic Shiladitya Sen has found something very significant. As early as 1958, in a letter to Soumitra Chattopadhyay, who was playing Apu in Apur Samsar, Ray wrote, “As Apu fights with prejudices, my own feelings get into the character”.

Ray also had a similar mindset, and he was also journeying like Apu from the local to the universal. Coming to you, for example, in Tabarana Kathe, we all can identify with the central character so magically portrayed by Charuhasan. And, in the end, when the clerk hides behind the typewriter, we also hide ourselves, and this trajectory makes the character universal. We all relate to him. So, do you think, somehow, even in the subconscious domain of your mind, you have been influenced by Ray?

Well, in one of my interviews, I stated, when it comes to Indian cinema, Ray was an important influence on my craft. But there were a great number of texts in Kannada literature that influenced me. But what I admired in Ray is that he kept on transforming his idiom from the first phase of Pather Panchali. And then in the second phase, when he made Pratidwandi and Aranyer Dinratri and many other great films, his approach to cinematic idiom changed entirely.

Ray’s portrayal of Apu marked a turning point in Indian cinema—an intimate, unsentimental gaze at boyhood that Kasaravalli says redefined how stories could be told on screen.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Yes, each of his films is different from the other. Girish, you have said Aparajito is an instance of pure cinema. I’ll not ask you to define what pure cinema is but do you not think the scene of Harihar’s death is one of best scenes in the history of cinema ever?

Yes, of course. I fully agree with you.

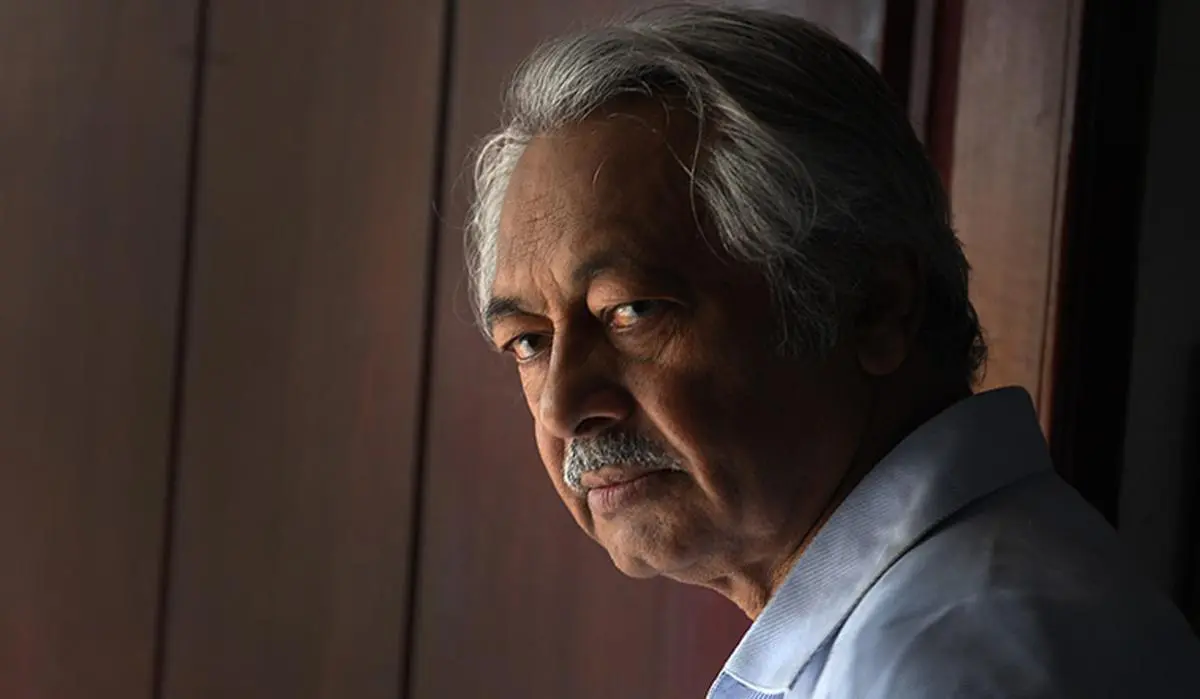

Essayist, academic, and translator Chinmoy Guha.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

You said Aparajito is pure cinema. I remember a similar comment by Arturo Lanocita who said, “The purity of the images corresponded to the purity of the subject. We have witnessed a kind of self-revelation of the Indian film art.”

Talking of Aparajito, I remember the monkey feeding scene in the film. It’s, again I say, purely magical. You cannot adequately explain it, but only enjoy the scene. It’s pure bliss, so full of a rhythmic ecstasy and this kind of a lyrical ecstasy is possible only in cinema.

On the other hand, as I was telling you, if you consider a film of the second phase of Ray’s career, then you’ll notice the drastic change in his approach to the idiom of cinema. In Aranyer Dinratri, Seemabaddha, or Jana Aranya, the blissful lyricism is gone, as it has been replaced by a grim montage of portrayals of lives with the least prospects and reasons to celebrate. Through the story of Somnath, lakhs of Somnath come to the fore. We are reminded of the unrest going on then, not only in Calcutta but in the entire nation and the entire world. The scene, capturing tonnes of job applications pouring in and out of the post office mailbox, speaks volumes about the grudges borne by the millions of educated youth wronged in the country.

If we closely observe this scene, then we’ll understand Ray does not use form merely as a tool to drive home the plot. In fact, Ray didn’t like the word “form”. Instead, he would call it “container”. And the “container” itself is a statement in Ray’s films. That’s why the form (I call it so for convenience) he uses in the city triptych Pratidwandi, Jana Aranya, and Seemabaddha is itself a statement. The chronicling of these three films in this order is apt because in Pratidwandi, Siddhartha, the protagonist, is highly idealistic. In the second film, Jana Aranya, Somnath, despite getting involved in some unfair business, still has his share of scruples. But Shyamalendu in Seemabaddha hardly hesitates in doing something immoral. This journey of moralistic degradation is deliberately maintained by Ray in the protagonists of his triptych just to reflect on the socio-political issues of the time. If this is not a political statement, then what is?

Don’t you think there’s a great amount of anger in Jana Aranya?

Yes. Siddharthais still very poetic, very romantic, hearing birds everywhere he goes. But, Shyamalendu is absolutely corrupted from the very beginning of Seemabaddha. And, from the middle of the film, Jana Aranya, Somnath is so full of unrealised anger.

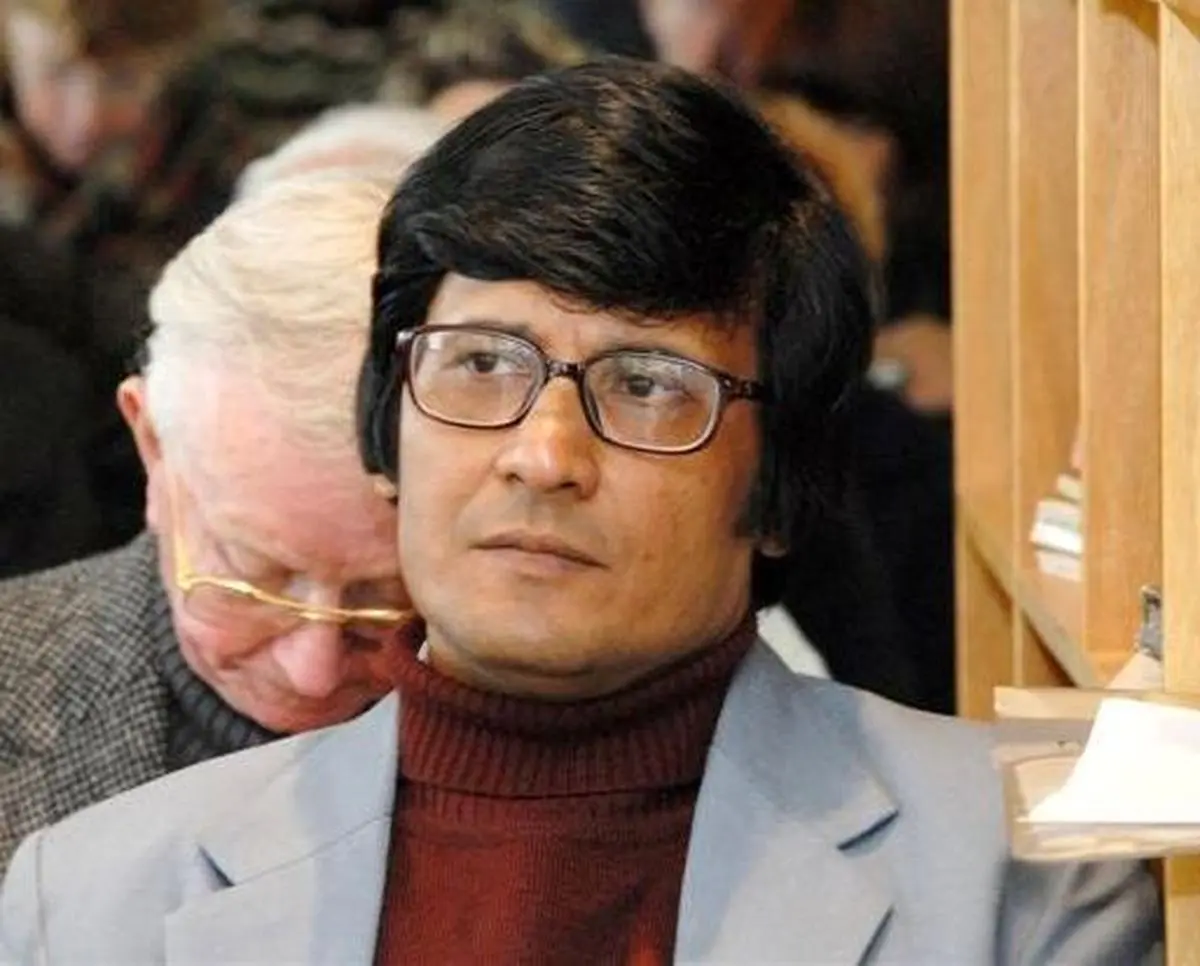

Chunibala Devi in a still from Pather Panchali. Kasaravalli draws parallels between Ray and the neo-realists, unpacking the distinct lyrical humanism that set Ray apart from global auteurs like De Sica and Renoir.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

True. Pauline Kael, speaking of the three protagonists of this triptych, has said, “It seems they are Apus in a corrupted state”. And, in another interview, you said that you liked the transitional aspect of Ray. I think, here too, the transition of Apu happens through difficult phases of conflicts and psychological crises and the pain and loneliness remain. One thing, Girish, I have found in your films too: an essence of loneliness. You often use darkness and other deep images in order to deal with several kinds of transitions through echoes and cross-references. This is, I think, one of the most important strands in your cinema. Don’t you think this is equally true of Ray?

Yes, very true. That is why, in films like Ghare Baire, he is very vocal about the political issues of the day. However, in his later films, his treatment of the subject becomes more restrained.

And as the understatement continued, Ray could play more with the complexities of the character, as in Seemabaddha. This I have found in your films too. Another thing that seems very interesting to me is that in your films, much like in the films of Ray, there are very strong female characters like Gulabi and Hasina. They sort of resist artistically any kind of oppression. I remember Derek Malcolm said, “Ray is best at showing how people live”. I think this applies to your films too. And I have often found many Apus in your films as well. I mean, in many of your films, I have found a constant resonance of Apu’s character. Am I correct to think so?

Yes. And in my works, just like in Ray, children play a very significant role. Children’s perspective is unadulterated and spontaneous, and I juxtapose their perspective with that of the adult world, where they have all kinds of calculations and permutations. You mention an important word: “manipulation”. Yes, Ray never tried to manipulate his audience. Rather, the audience enjoys a sense of autonomy when they watch Ray’s films. Ray was not judgmental. And that’s a great quality. You don’t get a film director every day who lets his audience enjoy this autonomy. And that is why, whenever occasionally Ray became judgmental, I had a problem with that. Like in the last scene of Mahanagar, where Arati helps the Anglo-Indian girl, or the nurse in Pratidwandi lights the match, Ray gives us a statement. Ray became judgmental.

I once interviewed Ray about this. Particularly speaking of Pratidwandi, he said that he never became judgmental. It was rather Siddhartha who got judgmental, and that’s why Ray had to bring in the negative shot.

[Smiling] But I still can’t accept it, because the entire film was not shown from Siddhartha’s perspective. For me, it’s a little problematic. Another problematic thing in Pratidwandi is the scene where Ray tried to make a statement by equating killing the hen with Naxalite insurgency. How could he equate the Naxalite movement to butchering a hen!

“Yes, Ray never tried to manipulate his audience. Rather, the audience enjoys a sense of autonomy when they watch Ray’s films. Ray was not judgmental. And that’s a great quality. You don’t get a film director every day who lets his audience enjoy this autonomy. ”Girish Kasaravalli

Well, Girish, we will now talk a bit about your films, such as Gulabi Talkies. So full of details taken straight from life! You show life as it is. I know there are various influences embedded in your unconscious. But I somehow feel you are responding to Ray in Kraurya (1996). Am I right?

Yes. Actually, when Ray passed away, I tried to rethink what his films actually meant to me. And then thinking of Pather Panchali, which dealt with the story of the lifestyle of people from the first leg of the 20th century, in Kraurya, I tried to recreate a response to Pather Panchali’s treatment of society by setting my film on the last leg of the century. But in between Pather Panchali and Kraurya, our society has undergone so many changes and has become even more dehumanised. So yes, that’s how Kraurya is, my response to Ray. But altogether, all my films deal with the issue of dehumanising. I think all great filmmakers do that. Even Kurosawa did that in all his films.

In your films, like in Ray, every detail is significant. Isn’t it?

I think you are talking about images. In that case, yes. But images are not merely visual. They are born out of sounds, like in Pather Panchali or even through architecture, like in Jalsaghar. When I want to use images in my films, I want them to be of three kinds: iconical, indexical, and metaphorical, and the juxtaposition of these three types of images…

Girish, sorry to interrupt you but I remember Adoor Gopalakrishnan saying, “Ray has touched the soul of images”. What do you think about this remark?

Yes, I also believe that and that’s what fascinated me, among other things, about Ray. Ray made use of several kinds of images, like the aural and the tactile ones, among others. Also, I would say that the imagery in the early Satyajit Ray films was quite different from that of the later Ray.

Yes, and you know I keep telling my students that the early Shakespeare was miles apart from the later Shakespeare. I think, like you said, this also applies for Ray. I also often compare Ray with Beethoven. The early romantic Beethoven cannot be found in the brooding Beethoven of the last phase.

Yes. I think that’s true for every artist. The world, the society, is constantly evolving and hence undergoing significant changes. So, artists, being a part of that society and world, will also change and evolve.

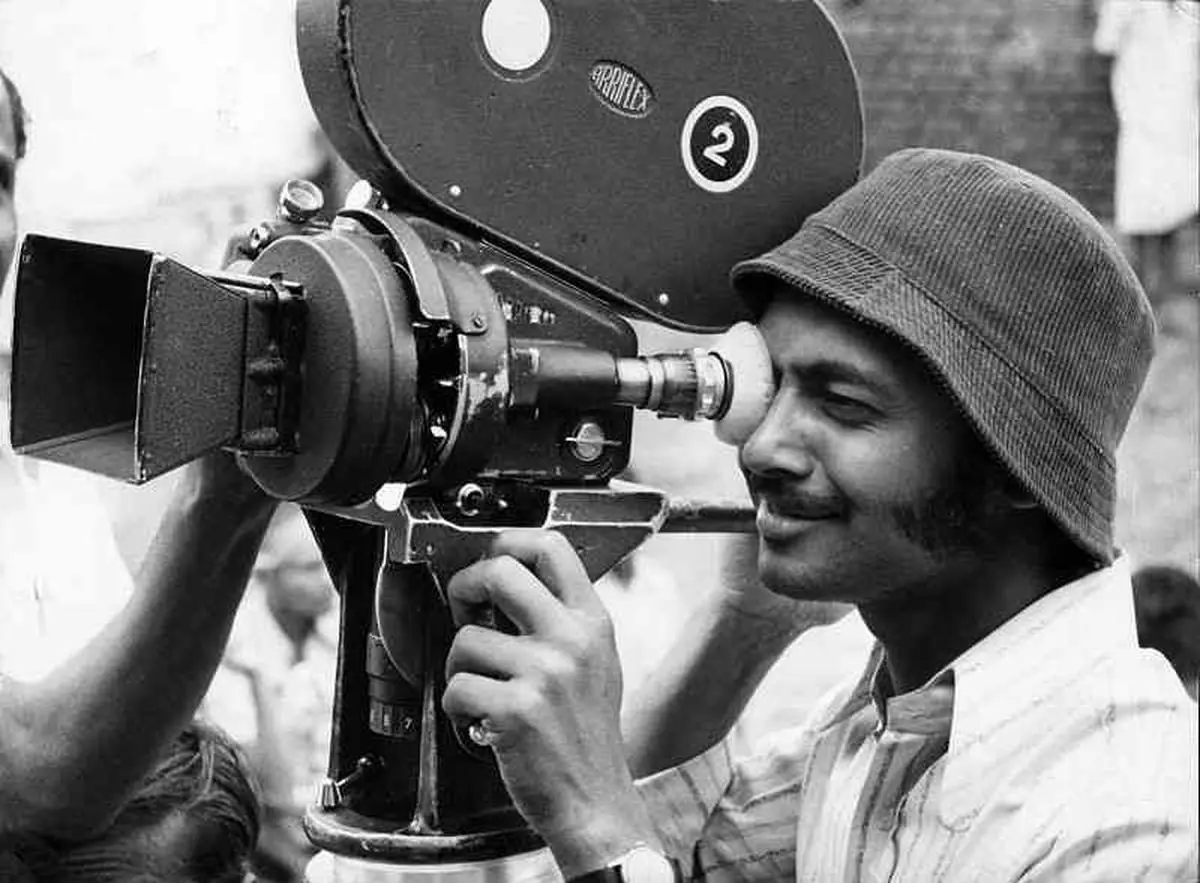

Girish Kasaravalli speaking at an event in Bangalore in August 2024.

| Photo Credit:

BHAGYA PRAKASH /THE HINDU

Ray also said, “I make films that have direct coordination with human breathing.” I think that’s also evident in the structures of his films. Do you think Western music helped Ray with those structures which he would eventually use in his films?

Definitely. Ray’s immense knowledge of music definitely helped him. Once someone understands the kind of music that has inspired Ray and has been formative in his artistic upbringing, it becomes easier to follow the pattern of his films. Besides, he repeatedly spoke of the influence of the symphonies, which he used so sporadically in films such as Charulata.

Also Read | The producer who saved Satyajit Ray’s films twice

Well, let me say it for readers that Ray saw Girish’s film Ghatashraddha (1977), which was based on Ananthamurthy’s short story, at Madras Filmotsav in 1979 and Ray was overwhelmingly impressed by the unique style of this young director. Everything in the film was totally different from all the films that had been made in India till then. The starkness juxtaposed with poetry, accompanied by the child’s idyllic innocence, created a whole new interpretative space.

And then, when Girish wanted to show Mane to Ray, the latter was already very ill and passed away in 1992, an incident that disturbed Girish greatly because he understood how important Ray was for humanity. Girish, I remember one critic remarking, “Ray seems to achieve more and more with less and less”. And, I think, we have to learn a lot from people like Girish Kasaravalli and Adoor Gopalakrishnan. But, here we are… almost at the end of our discussion.

What I would like to say now is that there’s a growing superficiality, lack of authenticity, and soul searching in Indian cinema, which hasn’t helped the matter. Of course, Girish and Adoor are bright exceptions. Tapan Sinha once said, “If one watches Bergman for 50 minutes, he will change”. I think, similarly, watching Ray can also be a life-changing experience. But before we end, I would like to remember that once in an interview given to Frontline, you talked about ‘samachittata’. Equanimity and stoicism. What do you think of it now?

Well, one of the great qualities of Ray is that he always maintains an emotional distance from his characters. Never does he allow too much of emotional extravagance or grandeur. So, the audience never gets carried away by a scene or a sequence in Ray. If you think of a film like Cleopatra, the very grandeur of Cleopatra’s first entry in the film takes all focus away from the essence of the film. But that is not the case with directors such as Ray, Kurosawa, Bergman, or even Renoir. In fact, Renoir was a great influence on Ray.

But I think Tarkovsky gets carried away… Doesn’t he get lost in the maze?

No, because in Tarkovsky’s case, it’s different. Because he is not talking about the mundane reality. What Tarkovsky talks about is very philosophical.

Alright! So we have come to the end of our discussion, as all good things must come to an end. Thank you, Girish, for explaining everything so lucidly. We all know that you have been working diligently for such a long time. I remember T.S. Eliot, who once said, “No artist of any art has his complete meaning alone.” The tradition also reverberates. Girish, you have also created your own artistic space. I will end with a statement by William Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.”

I hope we have been, in some ways at least, able to touch the infinite in Ray and some of the other giants of world cinema. And that’s all because of you, Girish. Thank you so much!

Thank you!

Chinmoy Guha is an essayist, translator, and scholar of French language and literature, currently serving as Professor Emeritus at the University of Calcutta.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/interviews/girish-kasaravalli-on-satyajit-ray-cinema-legacy-indian-filmmaking/article69522639.ece