Mansur al-Hallaj, a 9th-century Persian Sufi mystic, was brutally executed in 922 CE in Baghdad for proclaiming “Ana al-Haq“ (I am the Truth/God), a mystical utterance deemed heretical by orthodox authorities. His execution was more harrowing than that of prominent dissenters such as Socrates, Jesus, Sarmad, Hypatia, and Bruno.

Scholars note that Al-Hallaj’s proclamation significantly influenced Ibn al-Arabi’s (a Sunni scholar and poet) doctrine of “Wahdat ul-Wujud“ (Unity of Being), which shaped the sensibilities of future mystics. This mystical concept parallels the Upanishadic phrase “Aham Brahmasmi”, which asserts the oneness of self and the Absolute—a precursor to “Advaita Vedanta“, which holds that the Creator and the creation are not separate but fundamentally one. Poet Mirza Ghalib (1797–1869) too echoed this notion of divine unity, walking the fine line between belief and rebellion:

Na tha kuch to Khuda tha, kuchh na hota to Khuda hota,

Duboya mujh ko hone ne,na hota main to kya hota!

(When nothing was, God alone existed;

had nothing been, God would still prevail.

My illusion of separate self has drowned me;

were I not, I would be one with the Divine)

The philosophy also inspired Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911–1984) notably in his poem “Hum Dekhenge“ (We Shall Bear Witness), which was penned in 1979 to critique military dictatorship in Pakistan. Decades later, its powerful message continues to provoke.

On May 13, Maharashtra Police booked three individuals, under Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita, for allegedly endangering national integrity by simply reciting this poem. The poem concludes with the stirring lines:

Utthega ‘Ana al-Haq’ ka naara

jo main bhi hun aur tum bhi ho

aur raaj karegi ḳhalq-e-ḳhuda

jo main bhi hun aur tum bhi ho

The cry of ‘Ana al-Haq’ shall rise— I am part of it, and so are you. And the people of God shall reign—I am one of them, and so are you.

Also Read | Faiz Ahmed Faiz: A poet of defiance, transcending ideology

The verses depict the poem’s egalitarian ethos as they envision a collective uprising against tyranny, not in the name of any one religion, but in the name of shared humanity. Right-wing Hindutva zealots, however, often fixate on the line “Bas naam rahe ga Allah ka“ (Only God’s name shall prevail) in the poem besides “jab arz-e-ḳhuda ke ka’abe se, sab butt uthvae jaenge“ (when from the Ka’aba of God’s earth, all idols will be uprooted).

In classical Urdu poetry, such invocations function symbolically, shaped more by aesthetics than by strict theological assertions. Such metaphors often signify different meanings in different contexts.

Such misreadings have extended to other artists, too. Recently, a viral video of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan singing “Kuch to socho Musalman ho tum, Kafiron ko na ghar mein bithao“(Think for a moment, you are a Muslim, Do not let ‘infidels’ sit in your home.) was widely circulated, with the literal meaning of the lyrics—seemingly promoting communal segregation. But if the poem is understood in its entirety, it suggests the unpredictable nature of the beloved, and not religious denouncement. Ghalib’s following verses, for instance, also use the term hyperbolically to describe a fickle companion:

Qayamat hai ki hove muddai ka hamsafar ‘Ghalib’,

Vo kafir jo ḳhuda ko bhi na saunpa jaye hai mujh se!

(It’s sheer doom that my beloved becomes my rival’s companion, O Ghalib— That ‘faithless’ one whom I can’t even entrust to God!)

Another case is that of Pakistani poet Tufail Hoshiyarpuri (1914–1993). His ghazal “Sanson ki maala par simrun main pi ka naam“ shows the syncretic nature of South Asian literary traditions. Hoshiyarpuri merges Bhakti devotion with Sufi yearning. His work, featured in Soch Mala (A Garland of Thoughts), published by the Haryana-based Sham-e-Bahar Trust, showcases the cultural osmosis between Urdu and Hindi, and “Hindu and Muslim” devotional idioms. Hoshiyarpuri, originally from Hoshiarpur (now in India), migrated to Lahore post-Partition, became a leading radio personality, and wrote for Urdu and Punjabi films. His ghazal and Fateh Ali Khan’s soulful rendition testify to a shared civilisational ethos—an antidote to the binary narratives of nationalism.

Sanson ki maala par simrun main pi ka naam

apne man ki main janun aur pi ke man ki Raam

Ang-ang mein rachi hui hai yun Mohan ki preet,

Aik aankh Vrindavan meri duji Gokul Dhaam

(On the rosary of my breaths, I chant my beloved’s name;

I know my own heart, and Lord Ram knows his.

Mohan’s love is woven into every part of my being—

One of my eyes sees Vrindavan, the other sees Gokul Dham.

Similarly, Faiz rejected the parochialism that followed Partition. His poem “Subh-e-Azadi” (Dawn of Freedom) mourns disillusionment and tragedy accompanying Independence. In an editorial from The Pakistan Times (August 15, 1947), Faiz described the dawn of freedom as “black with sorrow and red with blood”.

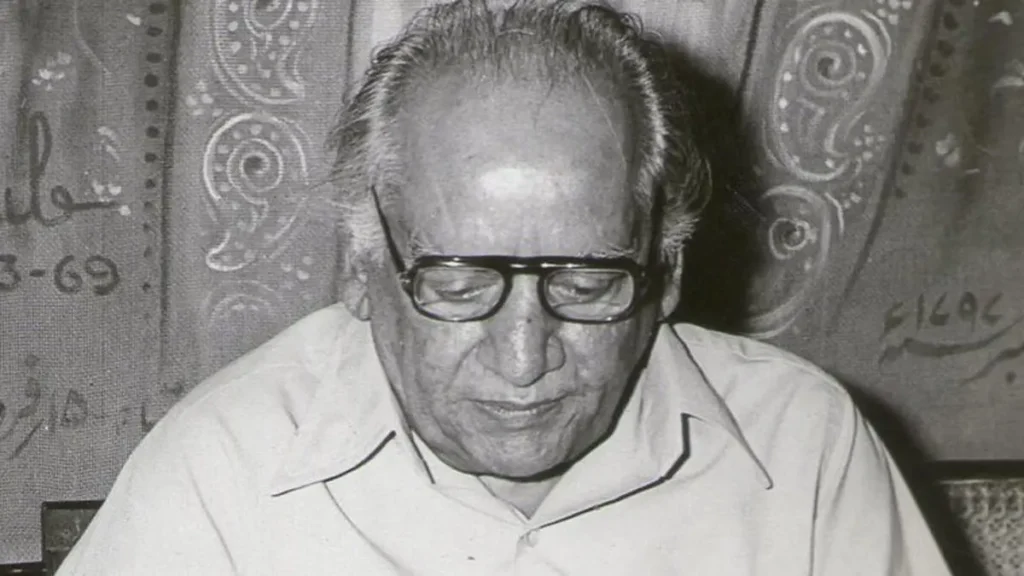

Born in Sialkot and educated in Lahore, Faiz taught briefly in Amritsar and resigned from the Army to work as a journalist. Known as the people’s poet, he was an avowed Marxist who was accused of being an atheist. A close associate of Sajjad Zaheer (a founder of the Communist Party of Pakistan and the All-India Progressive Writers’ Association), Faiz wrote some of his most celebrated poems while imprisoned, first in 1951 and later in 1958.

While exiled in Lebanon during the late 1970s, he edited Lotus, a literary magazine, while continuing to advocate for human rights, peace, and press freedom, before returning to Pakistan in 1982.

Incidentally, “Hum Dekhenge”, written in 1979, was a poetic indictment of General Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship. On February 13, 1986, Iqbal Bano (Pakistani singer) famously performed the banned poem in Lahore’s Alhamra Arts Council before a crowd of 50,000, donning a black sari in defiance of Zia’s cultural edicts. Her rendition ignited the audience, who erupted in chants of “Inquilab Zindabad” (Long live the revolution).

“Hum Dekhenge” has faced renewed scrutiny in India in recent years. The Maharashtra Police bookings reflect a troubling trend: the narrowing of intellectual and artistic space.

Poem in poetic spaces

In 2020, IIT Kanpur formed a committee to investigate its recitation during a protest against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, (CAA) on campus. The panel deemed the poem “unsuitable to the time and place” and recommended counselling for the students involved. In 2022, Faiz’s poetry was also dropped from a Class 10 NCERT political science textbook, sparking criticism from scholars who saw it as part of a broader attempt to sideline dissenting voices in public discourse.

Students during a protest demonstration against the CAA in 2019. Amid anti-CAA protests, students turned to Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge as a rallying cry, invoking a legacy of poetic dissent that unsettles state power and reclaims secular resistance from communal misreadings.

| Photo Credit:

R V Moorthy / The Hindu

In a 2011 interview with this writer, Salima Hashmi, the poet’s daughter, reflected on her father’s literary legacy: “Many who were condemned to death for demanding democratic rights during Zia-ul-Haq’s military regime went to the gallows reciting his poems. My father turned to poetry because he struggled to express his feelings openly—he was often silent. But when he did bare his heart, his words captured the pain of millions. His poetry was a voice of anguish and rebellion.”

Indeed, Faiz’s poetry talks about broader themes of resistance and humanism, often set against the backdrop of political oppression and social injustice, as seen during Pakistan’s turbulent periods. What could be a finer testament to Faiz’s progressive outlook than the following verse he penned:

Aaiye haath uthaaein hum bhi

Hum jinhein rasm-e-dua yaad nahi

Hum jinhein soz-e-mohabbat ke siwa

Koi butt, koi khuda yaad nahi

(Come, let us raise our hands in solidarity,

we, who have forgotten the rituals of prayer,

we, who know only the fervour of love,

no idol, no God, holds our reverence)

Also Read | Ismail Kadare (1936-2024): The writer who outsmarted a dictator

In “Hum Dekhenge”, as well, Faiz’s rebellion echoes the spiritual defiance of Sarmad Kashani (1590–1661), who was executed outside Delhi’s Jama Masjid by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. The Sufi poet was punished for his unorthodox beliefs, including refusal to recite the full Islamic Shahada (declaration of faith)—stopping at “La ilaha“ (There is no god) and not reciting the remaining part “Illallah“ (but Allah)—which were deemed heretical. (His red-coloured shrine is located just outside the eastern gate of the Jama Masjid, alongside the dargah of his Sufi master, Syed Abul.)

In Abul Kalam Azad: An Intellectual and Religious Biography, Ian Henderson Douglas notes Azad’s reflection on “Sarmad Shahid”, critiquing the ulama who condemned him for kufr (unbelief). Azad wrote: “Those deciding on ‘kufr’, standing on the floor of their madrasa and mosque, may consider their ‘throne’ as standing on a considerable height; yet Sarmad stood on that minaret of love from which the walls of Ka’aba and temple were of equal height, and where the flags of belief and unbelief waved together.”

To Faiz, poetry was not merely art—it was resistance. “Hum Dekhenge” is more than just a poem. It is a secular anthem that cuts through dominant dogmas to affirm the moral arc of justice. Despite persistent misreadings, its central message remains clear: Tyranny must fall, and humanity shall prevail.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/faiz-poetry-hum-dekhenge-ana-al-haq-resistance/article69632583.ece