What is the cost of being born a woman?

In Heart Lamp, a collection of 12 short stories, Banu Mushtaq provides various answers to the question—women pay with obedience, servitude, their bodies, and ultimately, their lives.

In the collection’s third story, “Black Cobras”, Aashraf chases after her husband Yakub, who abandons her once she gives birth to a third daughter. He remarries, dreaming that his new wife will give him a son, while Aashraf starves trying to feed the children and getting medicine for the sick infant. The mutawalli (caretaker of a waqf property) and other men in the village watch her run around, and do nothing to help even when she pleads with them.

Also Read | Banu Mushtaq: The rebel writer

Mushtaq’s stories show how the very notion of life is gendered, how women are valuable but not valued. Men long for sons; daughters arrive as symbols of disappointment and shame. Their presence is tolerated only because they serve a purpose: to clean, cook, and raise their siblings. They are not cherished, their labour is. Heart Lamp is an intimate portrait of the struggles, desires, and resilience of Muslim women, combining poignant storytelling with incisive social critique.

Speaking truth to power

Many of the stories are inspired by Mushtaq’s own life experiences, and the interactions she has had with other people. Written over the course of 33 years, the collection, translated by Deepa Bhasthi, has been shortlisted for this year’s International Booker Prize. Mushtaq is a celebrated Kannada writer, lawyer, and activist who emerged from the Bandaya Sahitya (Protest Literature) movement of the 1970s and 1980s—a progressive movement that challenged caste, class, and gender hierarchies in Karnataka. As the Booker judges note, Heart Lamp speaks “truth to power and slice[s] through the fault lines of caste, class, and religion widespread in contemporary society, exposing the rot within”—a powerful endorsement of Mushtaq’s fearless storytelling, moral clarity, and the political urgency that shapes her work.

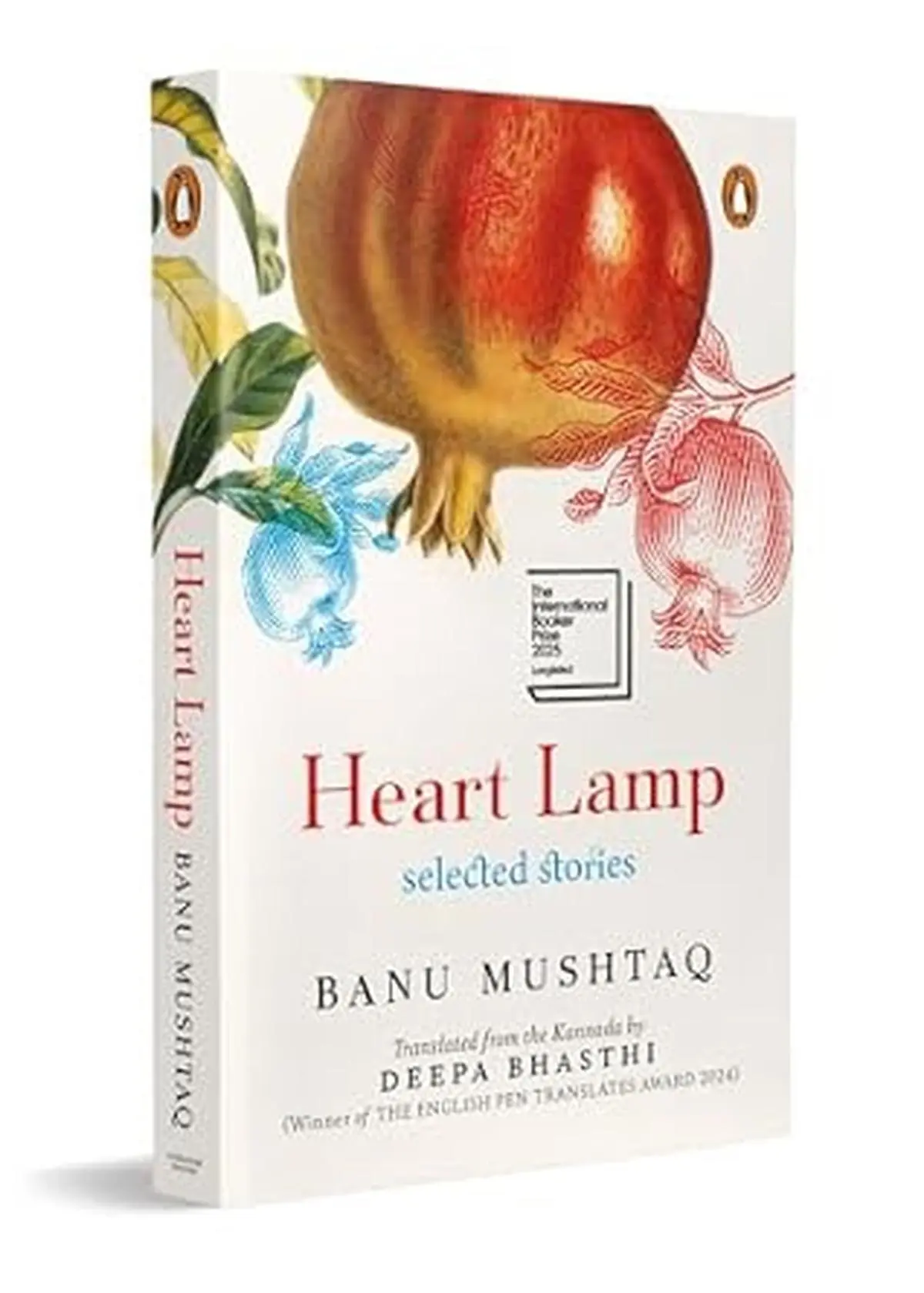

Heart Lamp: Selected Stories

Written by Banu Mushtaq, translated by Deepa Bhasthi

India Penguin

Pages: 224

Price: Rs.399

What makes each story compelling is its complex layering and unexpected narrative turns. The stories resist simplicity—the structures are often non-linear, and the woman introduced at the beginning may not be in focus at all, but a witness to another woman’s life. It serves to underline how the lives of all women are interconnected. Above all, Mushtaq’s women are neither saints nor victims—they are just human.

In “A Decision of the Heart”, all Akhila wants is some form of control over the domestic space which she shares one wall away with her mother-in-law. But her husband, loyal to his mother, weaponises Akhila’s frustration, marrying off his mother without her consent. When Akhila realises her mistake, it is far too late.

In another story, “High-Heeled Shoe”, Naseema intentionally drives a wedge between her husband and his brother Nayaz for her own benefit, ignoring the toll it takes on her sister-in-law, Asifa, who bears the brunt of Nayaz’s crazed delusions. In Mushtaq’s stories, women fight for each other, but they also fight each other. She reveals how women are pitted against one another under patriarchy, which does not let them realise that the entire gender is are under various degrees of oppression.

Hierarchies among women

Mushtaq details how class and caste shape the hierarchies among women, granting privilege here to deny dignity there. In the story, “The Shroud”, Shaziya, an affluent woman, casually neglects the final, modest request of Yaseen Bua—a widowed domestic worker. Her callousness is telling: Bua is poor, powerless, and of no social consequence to Shaziya, who feels no need to show her the respect she would offer to someone of higher standing. Oppression flows not just from men, but also among women.

Heart Lamp is a collection of 12 short stories.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

In writing about the lives of ordinary women, Mushtaq turns her gaze upon ordinary men too, showing how they do not necessarily need to beat up their wives to wield power. In many cases, their felt superiority expresses itself in just indifference. Religion comes to their aid. While Islam grants women financial rights and protection, men selectively interpret these teachings to suit their purposes. Under the display of piety lie greed, lust, and the routine denial of women’s autonomy. In stories such as “Fire Rain” and “Black Cobras”, the male protagonists are mutawallis preoccupied with maintaining a good public image, and their self-importance is fuelled by their social position, which blinds them to the emotional and material needs of their own families.

Mushtaq’s male characters, though often hurtful and dismissive, may not immediately appear monstrous—and herein lies the rub. Their indecency is so normalised and the bar is set so low for them, that it takes time for their awfulness to sink in. Entitlement, arrogance, and emotional negligence are rarely seen as forms of oppression and yet they shape the everyday lives of the women in the stories. At one striking moment, Yakub shouts at Aashraf, “Lei! If you who squats to pee has this much arrogance, how much arrogance should I, who stands to piss, have?”

Let there be daughters

This is why all the women in Mushtaq’s stories wish their daughters to be educated, independent, and empowered. Their resistance is quiet but resolute: a determination to break the cycle, not for themselves, but for their daughters. In the titular story, “Heart Lamp”, even as the “lamp in Mehrun’s heart had been extinguished a long time ago”, she still hopes through her daughter. The thread of intergenerational struggle and resilience runs through the collection; Mushtaq’s women may be battered by circumstance, but they do not surrender.

It is no accident that many of these stories do not have neat endings. Mushtaq resists resolution because the struggles of her characters are ongoing battles. Within that tension lies possibility as women continue to resist, reclaim, and imagine new futures for themselves.

Basthi’s translation beautifully captures Mushtaq’s signature dry humour and the characters’ quirky personalities. She blends English with local expressions and Kannadiga mannerisms in a way that global audiences can connect with Mushtaq’s work. Bashti avoids italics and footnotes, inviting readers to experience the text without interruption, allowing them to absorb new words naturally and immerse themselves in another language as they read.

Also Read | Unveiling answers

Here, a minor niggle. Since the stories were written over decades as separate pieces, not intended to be part of a collection, they seem repetitive at times. The themes and characters seem a bit predictable after a while.

The anthology closes fittingly with “Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord!”—the title the cry of a long-suffering woman to god. Learning to empathise by getting into somebody else’s shoes is the beginning of the process of change. The woman flings the challenge at god himself: “If you were to build the world again, to create males and females again, do not be like an inexperienced potter. Come to earth as a woman, Prabhu!

“Be a woman once, Oh Lord!”

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/literature/banu-mushtaq-heart-lamp-international-booker-muslim-women-fighting-patriarchy/article69556675.ece