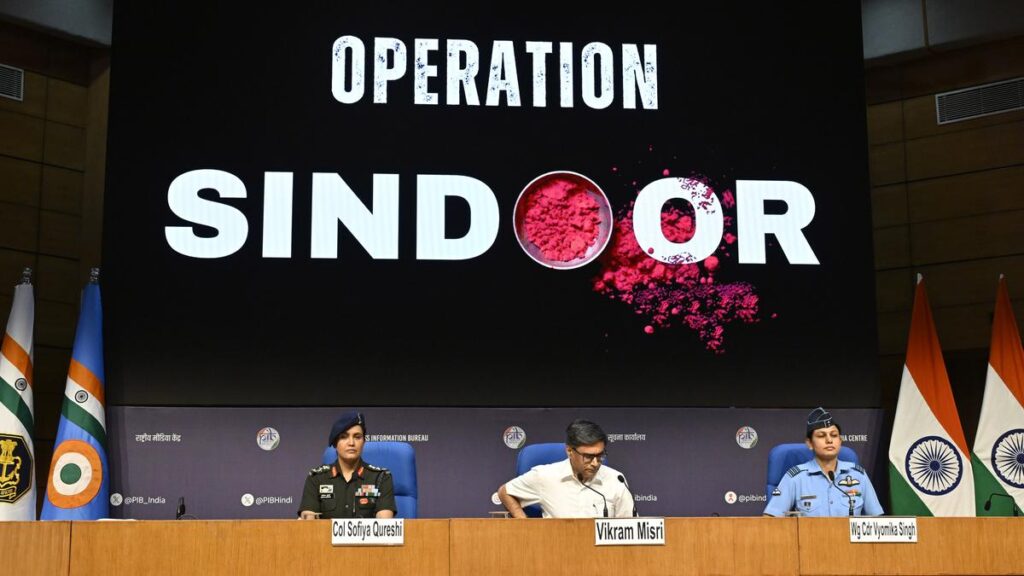

Foreign secretary Vikram Misri (centre) along with Col. Sofiya Qureshi (left) and Wing Commander Vyomika Singh (right) during a press briefing regarding “Operation Sindoor” at National Media Centre in New Delhi on May 7, 2025.

| Photo Credit: The Hindu

India and Pakistan on Saturday (May 10, 2025) agreed to halt “all firing and military action” after several days of heightened tensions between the two nuclear-armed neighbours. The announcement comes in the aftermath of precision strikes conducted by the Indian armed forces against terrorist infrastructure in Pakistan and Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir, in response to the Pahalgam massacre, which claimed the lives of 26 civilians.

While India’s Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri described the strikes as “measured and non-escalatory,” Pakistan denounced them as a “blatant act of war” and alleged civilian casualties. With hostilities now suspended, how will India’s military response be assessed under international law?

Can India invoke the right to self-defence?

Article 51 of the United Nations (U.N.) Charter carves out a narrow exception to the general prohibition on the use of force outlined in Article 2(4), which bars member states from threatening or using force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. It allows the use of force solely in the exercise of self-defence following an armed attack. While the Charter does not define what constitutes an armed attack, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in Nicaragua v. U.S. (1986), interpreted it as “the most grave form of the use of force,” indicating that not all uses of force meet this threshold. Although the Foreign Secretary’s statement did not explicitly invoke Article 51, his description of the missile strikes as a “response” to the Pahalgam terror attack appears to be a reliance on this principle.

However, this right is not unfettered. Article 51 imposes a procedural obligation on member states to “immediately” report to the U.N. Security Council (UNSC) any military measures taken in self-defence. The UNSC then assumes the authority to undertake any action necessary to “maintain or restore international peace and security”. In apparent adherence to this requirement, on May 8, 2025, the Foreign Secretary briefed envoys of 13 out of the 15 UNSC member states on India’s missile strikes. Pakistan’s envoy was not invited, and Sierra Leone remained unrepresented owing to the absence of an envoy in New Delhi.

Can the right be exercised against non-state actors?

The U.N. Charter governs only the conduct of states and, by extension, state-sponsored uses of force. Non-state entities such as terrorist organisations and insurgents operate outside this legal framework, complicating the Charter’s inherently state-centric design. Following the 9/11 attacks, the growing role of such actors in armed conflict prompted some states, most notably the United States, to argue that the right of self-defence under Article 51 extends to military action against non-state actors like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS).

However, the ICJ has adopted a more restrictive interpretation. In cases such as Nicaragua and Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda (2005), it has held that an armed attack under Article 51 includes acts by non-state actors only if they are carried out “by or on behalf of a state.” Accordingly, attribution to a state remains a necessary condition for invoking the right of self-defence under international law.

“It is evident from the Foreign Secretary’s statement that India has not contextualised the missile strikes within the international law framework. However, by asserting that ‘Pakistan-trained terrorists’ were responsible for the Pahalgam attack and describing it as part of ‘Pakistan’s long-standing record of cross-border terrorism,’ India seems to have directly attributed the attack to Pakistan,” Prabhash Ranjan, professor at Jindal Global Law School, told The Hindu.

What is the ‘unwilling or unable’ doctrine?

An emerging doctrine in international law permits the use of force in self-defence against non-state actors operating from the territory of another state, when that state is deemed “unwilling or unable” to neutralise the threat. The United States has been a leading proponent of this doctrine, invoking it to justify the 2011 military operation that killed al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in Pakistan, and the 2014 airstrikes against the IS in Syria, from where the network was orchestrating other terrorist attacks. However, states such as China, Mexico, and Russia have condemned such military operations for undermining the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the host state as well as the U.N.’s collective security apparatus.

However, India’s stance on the doctrine remains ambiguous. At a UNSC Arria Formula meeting in February 2021, India affirmed that the right of self-defence extends to attacks by non-state actors and noted that such groups often exploit the sovereignty of host states as a “smokescreen”. It then outlined three conditions for invoking such a right: i. The non-state actor has repeatedly undertaken armed attacks against the state. ii. The host state is unwilling to address the threat posed by the non-state actor. iii. The host state is actively supporting and sponsoring the attack by the non-state actor. However, legal scholars have pointed out that it is unclear whether these conditions must be met cumulatively or can be applied independently. If read conjunctively, India appears to require state attribution, rendering its support for the doctrine uncertain.

Dr. Ranjan noted that the Foreign Secretary’s remarks that Pakistan had taken “no demonstrable step” to act against terrorist infrastructure in the fortnight following the Pahalgam attack and that the country has long served as a “haven for terrorists” indicate a reliance on the “unwilling or unable” doctrine. “This doctrine does not require state attribution for attacks by non-state actors, thereby lowering the threshold for invoking self-defence,” he explained. “However, this principle is contested and lacks the consistent state practice and opinio juris necessary to crystallise into a rule of customary international law.”

Is proportionality essential in military responses?

Military operations conducted in the exercise of self-defence must comply with the customary international law principles of necessity and proportionality. It is generally accepted that a host state’s unwillingness or inability to neutralise non-state actors engaged in cross-border attacks fulfils the necessity requirement. However, the Leiden Policy Recommendations on Counter-Terrorism and International Law (2010) emphasise that the use of force against the host state’s armed forces or facilities is permissible only in “exceptional circumstances”, such as when the state actively supports the terrorists. On proportionality, there are two competing views: a narrow interpretation limits force to what is necessary to stop an ongoing attack, while a broader view permits action to repel and prevent future attacks reasonably anticipated under the circumstances.

“Since the military strikes on May 7, 2025, were directed solely at terrorist infrastructure, without targeting Pakistani military assets or civilian settlements, they would satisfy the requirements of necessity and proportionality”, Dr. Ranjan said.

What lies ahead?

If the ceasefire agreement between India and Pakistan fails to hold, the UNSC could adopt a resolution calling for an immediate cessation of hostilities. It may also vote on a subsequent resolution to address any further violations, including the imposition of sanctions or the deployment of its own peacekeeping or military forces. However, the successful passage of such resolutions is likely to be shaped by the geopolitical interests of the Council’s permanent members, each of whom holds veto power.

Published – May 10, 2025 09:39 pm IST

Source:https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/how-will-indias-military-response-be-assessed-under-international-law/article69552517.ece