Thirty years ago, at the Cannes Film Festival in 1995, the Caméra d’Or award for the best debut feature was awarded to a film called The White Balloon, a tender portrayal of childhood in a harsh adult world. Told through the eyes of a young girl hoping to buy a goldfish and seeking help from adult strangers who ignore her, the film was compassionate in its portrayal of the gradual slipping away of hope and innocence. The winner, Jafar Panahi, a young Iranian director with a perpetual cheeky grin on his face, accepted the award at a time when dissent in Iranian cinema was not widespread.

Panahi went on to make several acclaimed films after The White Balloon, including The Mirror, The Circle, Crimson Gold, and Offside, but it did not take him long to get in the crosshairs of the Iranian regime. When he took an active role in a protest movement along the likes of the Arab Spring, called Iranian Green Movement, the regime took notice and put him under a 20-year ban from making movies or travelling outside the country.

Also Read | Tell all the truth but tell it slant

If the world had not paid attention to the Iranian auteur with steely moral integrity to rage against the mullah machine until then, it took notice when an empty chair represented Panahi, who was part of the jury in the Berlin Film Festival of 2011, because the Iranian government had banned him from attending it. World cinema’s leading voice of dissent was born.

It was Just an Accident: A thriller caper

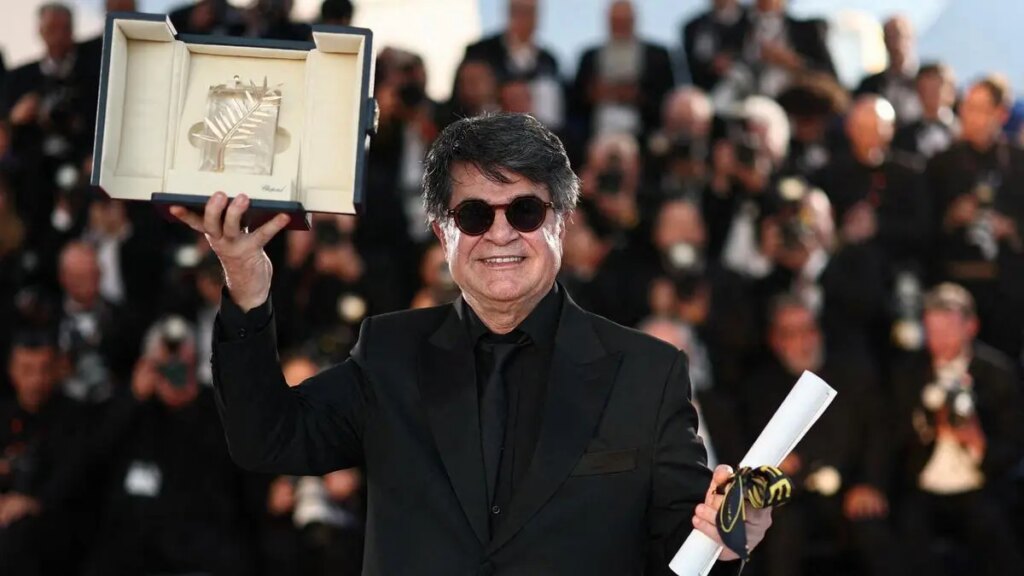

In what is certainly a full-circle moment in his life, Panahi travelled to Cannes this year, screened his film It was Just an Accident in the competition section, and won the most prestigious Palme d’Or award in the recently concluded 78th Cannes Film Festival. The dissident filmmaker’s visit to Cannes was kept under wraps and revealed only after he landed at the Nice airport, days prior to the premiere of his film. Banned from filmmaking and imprisoned multiple times, Panahi went on making films and sending them to festivals, the copies hidden and smuggled out of the country in creative ways.

It was Just an Accident is a thriller caper in which an ex-prison guard, a regime enforcer, is kidnapped by a motley crew of people whose lives have been upturned by his actions—an arrest for not wearing a headscarf, imprisonment for arbitrary reasons, and torture in prison after being arrested in protests. In hauntingly unspooling visuals, Panahi’s subjects weave in and out of indecision, betraying their own morality while they decide how to punish the man. The film is a stark departure from Panahi’s previous films—there is no mix of fiction and non-fiction like in his recent works, No Bears or Taxi Tehran; there is no quiet meditation. It is a direct confrontation with the fact of living in a system that produces broken lives and forces people into rancorous retribution.

A still from It was Just an Accident, directed by Jafar Panahi.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

Like every film since Panahi’s initial arrest in 2009, this one too was shot secretly without permission from the authorities. How the film was sent to the festival is still unclear, but the regime seems to have allowed him to travel outside the country.

“The regime sometimes imprisons opponents it can’t punish severely but it also can’t keep them in prison forever,” said Ardeshir Tayebi, an Iranian journalist who lives in exile in Germany. He added that in order to exercise strict control on its film industry, the regime dictates what gets made and served to people, by harassing some filmmakers while supporting others.

Hijab controversy

Iranian cinema is controlled by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The Iranian body called Owj Arts and Media Organization is a propaganda arm of the regime. The films they produce are not necessarily about Islam or on religious themes, and some of them even have a very modern outlook.

For example, Saeed Roustayi, whose film Woman and Child was also in the competition section in Cannes this year, had his film produced by this very organisation. Even though it appears to portray the struggles of women in a patriarchal society with the judiciary heavily skewed against them, women wear hijab indoors, even in a women-only household, in the film.

This has not gone unnoticed in Iranian circles. Yalda Moaiery, a well-known Iranian photojournalist, wrote on X: “Saeed Roustayi made a film adhering to the mandatory hijab rules, and the cast even appeared on the red carpet wearing something resembling the hijab! Then, he dedicated the film to filmmakers who have been banned from working due to protesting compulsory hijab! Isn’t that a bit cunning, Mr. Roustayi?!”

“In Panahi’s films, the camera never enters any homes. Even if it follows a character to their doorstep, it stays outside and doesn’t go in. That’s because Panahi refuses to show women wearing hijab inside their own homes. Wearing hijab on the streets of Iran is normal, but no Muslim woman wears it at home. However, the regime forces filmmakers to depict women wearing hijab indoors as well,” said Tayebi.

Widespread appeal

While Panahi’s legacy is revered in the West, in his own country, his movies have hardly been released. Films by Panahi and the recently exiled Mohammad Rasoulof are no longer as widely seen inside Iran as they used to be. They deal with serious social issues and do not appeal to a mainstream audience because they are not meant to entertain. Despite all this, people in Iran still find ways to access these films.

Jafar Panahi poses with Juliette Binoche, Jury President of the 78th Cannes Film Festival, Cate Blanchett, Master of Ceremony Laurent Lafitte, and the team of the film during the closing ceremony of the 78th Cannes Film Festival in Cannes on May 24.

| Photo Credit:

BENOIT TESSIER/REUTERS

“When I was a teenager, there were street vendors who used to sell the latest international films on DVD. These films were all illegal and sold without government permission. Among their collections, you found Panahi’s movies. I remember watching The Circle and Offside when I was just a teenager, and they left a deep impression on me. I think Panahi is truly a great filmmaker and storyteller who, because of his artistic integrity, naturally ended up opposing censorship and dictatorship,” said Tayebi.

Panahi’s appeal is widespread. Prantik Basu, a short filmmaker who is currently working on his debut feature titled Dengue, said he turns to Panahi’s work whenever he feels caught in a creative gridlock. “Filmmaking isn’t easy, even when one has all the resources. Panahi’s work reminds me why we keep at it: because cinema is not only an expression, it’s also a need. I especially like Offside, the first Panahi film I saw and often revisit, for the sheer joy, hope and perseverance.”

At It was Just an Accident’s premiere, Panahi said amidst the roar of the standing ovation, “The day I was released from prison, as I emerged and looked behind me at the tall walls, I didn’t know how to feel…was I relieved or anxious? My dear friends still remained imprisoned behind those walls. I asked myself, ‘What am I going to do outside?’”

Panahi has been giving interviews saying that he has every plan to return to his homeland even though the scrutiny and oppression, despite (or because of) his Palme d’Or win, is only bound to intensify.

Also Read | Cinema cannot change the world: Goutam Ghose

“Whether I am banned or not, I still do not wish to make the kind of films they want me to make. I can’t follow the formal or legal way of filmmaking. I want to make the films I feel are necessary to make. It always remains underground or parallel to the official system,” he told Screen magazine. Unlike fellow filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof, who sought asylum in Germany last year, Panahi has been clear about his intentions to go back after his travels.

“I believe part of the regime’s strategy is to pressure artists, activists, critics, and journalists to force them to leave the country. They probably think that if they separate an artist from the people they grew up with and create for, that artist will lose their impact, and it’s probably true. That’s why I think Panahi wants to return,” Tayebi says. Based on social media reports, Panahi has already landed in Tehran. The regime has allowed him in, but his future as a filmmaker who’s able to realise his projects freely remains unclear.

Upon winning the Palme d’Or, Panahi said touchingly, “I hope the moment we all long for and fight for reaches us soon, and we are no longer obligated to go underground to make our films.”

Prathap Nair is a freelance culture journalist based in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/cinema/jafar-panahi-cannes-2025-palme-dor-return-iran-censorship/article69619973.ece