The government’s decision to include caste data in the upcoming census has sparked debate about state-led enumeration. While proponents see it as advancing equitable policy, critics fear identity politics, data manipulation, and deeper social divisions. Interestingly, such concerns are not new, and echo colonial India’s experience when censuses became political battlegrounds rather than neutral scientific exercises. This struggle played out vividly in the North-Western Provinces and Oudh during the 1901 and 1911 censuses.

The language columns in these censuses, though presented by colonial authorities as tools for collecting objective demographic data, became flashpoints of cultural and religious contestation. Far from reflecting linguistic realities, they transformed into arenas where Hindi-speaking Hindus and Urdu-speaking Muslims competed for numerical and symbolic dominance. This was not simply an administrative issue but a powerful demonstration of how language, religion, and politics converged to intensify communal polarisation.

Notably, the 1891 census did not provoke such tensions, as it made no attempt to distinguish between Urdu and Hindi. Instead, the term “Hindustani” was used for both. As D.C. Billie, the provincial superintendent, observed, most people reported their mother tongue as “Hindustani.” This broad, inclusive label helped avoid stoking communal tensions. But the lack of differentiation also left the door open for future disputes—especially as language increasingly became a proxy for religious identity.

Also Read | Understand every caste-count, not just the broad categories

The 1901 census unfolded in a climate already inflamed by the Hindi-Urdu controversy, which had intensified after MacDonnell’s 1900 resolution allowing the use of both Nagari and Persian scripts in official correspondence. Though framed as an administrative compromise, it was interpreted along communal lines: Hindi supporters saw it as long-overdue recognition, while Muslims viewed it as a threat to Urdu’s established status. By the time of the census, linguistic antagonism had seeped deep into the social and administrative fabric.

Accusations of data manipulation

In this charged context, the 1901 census became a contest for cultural visibility. Allegations of data manipulation surfaced rapidly. Hindi-speaking Hindus accused Muslim enumerators of recording Urdu as their language regardless of actual usage. Urdu-speaking Muslims made the opposite charge against Hindu enumerators. These were not isolated grievances; they were aired prominently in the vernacular press. Arya Mitra (Moradabad) reported in March 1901 that Urdu was being wrongly recorded for Hindi speakers due to an overrepresentation of Urdu-leaning enumerators. Sahifa (Bijnor) countered with accusations that Hindi was falsely recorded in Urdu-speaking regions.

These disputes went beyond clerical errors; they reflected a deeper struggle over communal identity. For many Hindus, declaring Hindi—especially in its Sanskritised form—was an assertion of cultural and religious identity, and a repudiation of Urdu’s Islamic and Persianate associations. Organisations like the Nagari Pracharini Sabha and newspapers such as Prayag Samachar urged Hindus to identify as Hindi speakers, even if their everyday speech included Persian or Arabic words.

Muslim publications often rejected this binary. Al Bashir (Etawah) argued that linguistic differences were overstated and that both communities essentially spoke “Hindustani.” The division between Hindi and Urdu, it claimed, was a colonial fabrication with dangerous consequences. Yet even those advocating linguistic unity felt compelled to defend Urdu’s status. As the historical language of administration, education, and elite culture, Urdu symbolised continuity and power. Its marginalisation was seen as a political loss. Muslim elites mobilised to safeguard its demographic weight and symbolic standing.

In some instances, both communities took proactive steps to influence enumeration. Agra Akhbar (January 1901) reported that Hindu supervisors instructed enumerators to list all Hindus as Hindi speakers. Muslim newspapers like Shararah (Moradabad) accused Hindu enumerators of classifying Persianised dialects as Hindi. Tohfah-i-Hind (February 1901) even proposed a crude communal formula: all Hindus as Hindi speakers and all Muslims as Urdu speakers.

The controversy reached the highest levels of the census bureaucracy. R. Burn, Superintendent of the 1901 Census, acknowledged: “While the preliminary operations were in progress complaints were made by Hindus, on the one side, that Muhammadan enumerators were recording the language of illiterate villagers as Urdu in places where it was certainly something different, and by Muhammadans that Hindus were recording Hindi where Urdu was more correct.” This confirmed that the census had become a site of contestation, with enumerators themselves implicated in the communal divide.

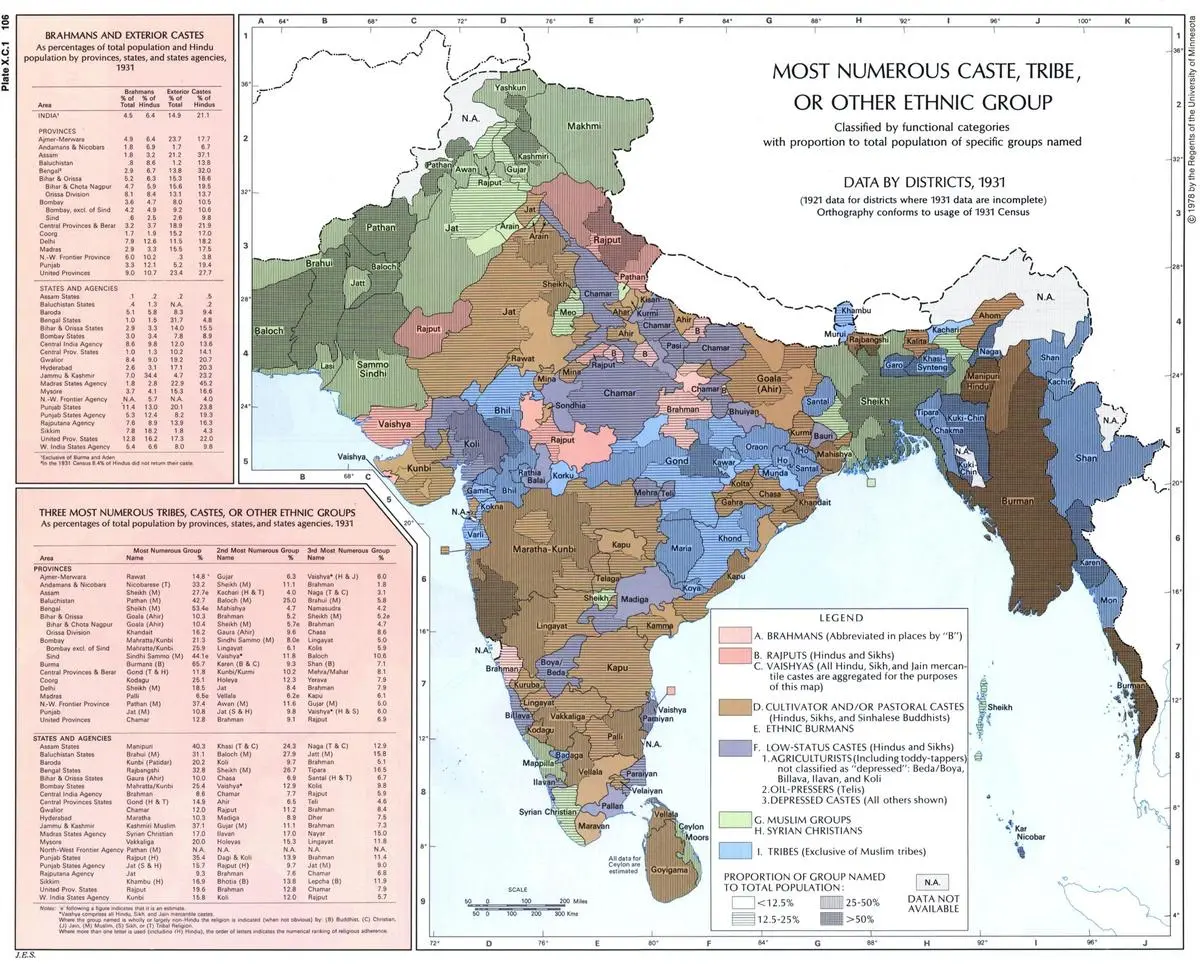

“Most numerous caste, tribe, or other ethnic group” in India by district, according to the 1931 British Census.

| Photo Credit:

ArainGang/X

By the end of the 1901 enumeration, the credibility of the language data had been deeply compromised. What was meant to be an objective demographic exercise was widely perceived as politically manipulated. The language column, rather than being a neutral category, had become a medium for asserting religious and political identity.

The 1911 census

The 1911 census, led by E.A. Blunt, only heightened the crisis of credibility. Reports of misconduct similar to those in 1901 resurfaced—this time with greater urgency. Hindu publications like Abhyudaya and Arya Mitra alleged that Muslim enumerators coerced Hindus into declaring Urdu as their mother tongue, sometimes under threat of legal consequences. Reports from Phulpur (Azamgarh), Balrampur, and Moradabad detailed instructions to census staff to default to Urdu for Hindu respondents.

Muslim periodicals continued to advocate for a return to the more inclusive “Hindustani”. Al Bashir reiterated that Hindi was an archaic, ceremonial language, whereas Urdu—or Hindustani—remained the common vernacular for both communities. They condemned efforts to split the languages along communal lines as artificial and divisive. Yet despite these appeals, anxieties among Muslims were growing. The categorisation of Hindi and Urdu was no longer just a linguistic issue—it had implications for education funding, government jobs, and political representation. A drop in Urdu speakers could justify cuts to Urdu-medium schools or reduce Muslim representation in state structures. Each census form became a potential site of marginalisation.

Also Read | What the caste census could do to Bihar’s election math

Even E.A. Blunt admitted the distortion caused by these tensions. He wrote: “There was a good deal of excitement, and it is probable that the figures were to some extent vitiated thereby.” His observation confirmed that the census had become less a tool for governance and more a mirror of deepening communal anxieties.

The colonial state’s ambivalent role

The colonial state found itself in a paradox. While officials like Burn and Blunt tried to enforce procedural neutrality, the very act of categorising people by religion and language had already politicised the process. Rather than remaining passive record-keepers, the colonial administration and its bureaucratic apparatus became complicit in shaping communal consciousness.

By 1921, the destabilising effects of linguistic classification were acknowledged more explicitly. That year, under Superintendent E.H.H. Edye, enumerators were instructed to record “Hindustani” for those using the region’s common speech, unless respondents specified another language. Edye admitted that past efforts to distinguish between Hindi and Urdu had inflamed communal tensions. The new policy implicitly recognised the political costs of earlier census practices. But the damage had already been done. The 1901 and 1911 censuses had crystallised the perception of Hindi as the language of Hindus and Urdu of Muslims. Shared vernacular heritage gave way to rigid, communal identities. Census data ceased to be neutral facts; they became political tools for asserting dominance and shaping policy.

Summing up, the manipulation and communalisation of census data in early 20th-century north India illustrate how linguistic identity became inseparable from political power and cultural assertion. The Hindi-Urdu controversy turned the census into a symbolic battleground where numbers signified more than demographics—they conveyed legitimacy. In trying to classify and govern, the colonial state ended up deepening the very divisions it sought to manage. The episode is a cautionary tale of how bureaucratic categories can inflame social tensions and how language, when politicised, can become a powerful fault line in the politics of identity.

Mohd Kashif is a Ph.D. scholar, Department of History, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/social-issues/colonial-caste-census-hindustani-hindi-urdu-politics/article69598005.ece