Warding off flies with one hand, and holding a weathered mobile phone in another, Kesari Bagri, 40, tries hard to keep her tears from brimming over. She is speaking to her ageing parents, both in their 70s, over a video call. They live in a village in Hyderabad division, Sindh, Pakistan; she is in one of the refugee camps in Rohini, north-west Delhi.

Since the political escalation between India and Pakistan after the Pahalgam attack in Kashmir that killed 26, Kesari has tried speaking to her parents every day over a call even if for a minute. She is worried about their future in a country where Islam is a state religion and Hindus, a religious minority. As per Pakistan’s 2023 census, 3.8 million Hindus live there, up from 3.5 million in 2017, constituting 1.6% of the population, the Press Trust of India had reported in 2024.

Each time Kesari disconnects the phone, she wonders whether it is the last time she speaks to them. She is one of the hundreds of Pakistani Hindus whose lives continue to move in a rhythm matching that of the improving or worsening relationship between the two neighbouring countries.

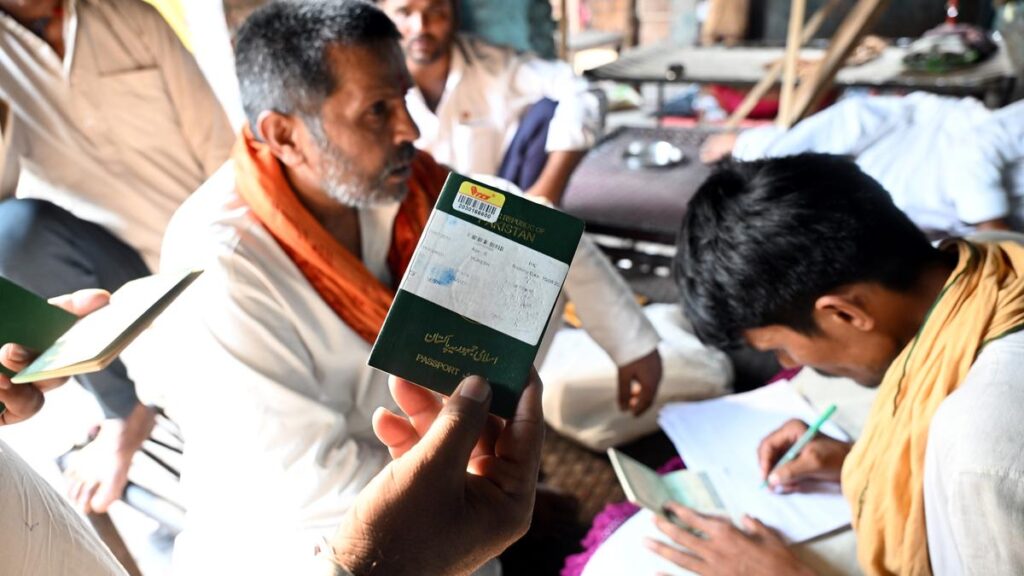

“When the government first said all those who hold Pakistani passports need to go back, we were nervous since nobody at the camp has got Indian citizenship yet (under the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019),” says Kesari, whose camp has 300 people as per the camp head.

Despite the escalations and the Ministry of Home Affairs’ (MHA) orders directing Pakistani nationals to leave the country by April 29 or face imprisonment for three years, the Pakistani Hindu community was assured that they would not be deported, she adds. Over the media accessed over their phones, they heard that those holding long-term visas (LTVs) could stay. The MHA also clarified that Hindus from Pakistan who had sent their applications for LTVs could stay on.

The MHA’s annual 2023-24 report says that 1,112 LTVs had been granted to members of minority communities from Pakistan that financial year. Hindu Singh Sodha, the president of the Seemant Lok Sangathan, a group that advocates for the rights of Pakistani minority migrants in India, says that there are 10,000 Pakistani Hindus whose LTV application is pending with the MHA for more than two years.

A part of the majority

Over the past couple of weeks, India and Pakistan have suspended ties, and India has expelled Pakistani diplomats. India banned the import of all goods originating in or transitioning through Pakistan. The Indus Waters Treaty of 1960 was suspended and restrictions imposed on Pakistan’s use of Indian airspace. No Pakistani mercantile ship is now allowed into Indian waters and no Indian ship will dock at a Pakistani port. Pakistan also halted all trade with India, closed its airspace to Indian aircraft and expelled diplomats.

Kesari’s husband, like many of those in the camp, is a farmer who cultivates wheat and vegetables like he did in Pakistan. Their three children study in a Delhi government school, where they say they faced no problem with admission.

Kesari Bagri (in brown) at the refugee camp in Rohini.

| Photo Credit:

SUSHIL KUMAR VERMA

Recalling the days since the Pahalgam attack on April 22, Kesari says the fear of being deported was much less than the fear of her kin in Pakistan being harmed. “Every time people call for a war between these two countries, I fear that I will never be able to see my parents again,” she says.

Like many other Pakistani Hindus, Kesari’s family too had decided to move to India for their children’s future and for a better life. “Being a religious minority in a country where your voice and pain do not matter causes a lot of mental anguish. When our relatives, who had moved to India since 2011, started telling us that crossing the border would help us, we put together every rupee to get our passports,” she says.

Kesari and her husband, with their children, spent over ₹5 lakh in Indian currency to get their passports and visas and come to Delhi. By 2015, when they arrived, there were already over 500 Pakistani Hindus living in three refugee camps near north Delhi’s Majnu Ka Tila, Signature Bridge and Rohini.

In Majnu Ka Tila and Rohini, there are exposed brick structures for them to live in; at Signature Bridge, with 932 people, it’s just bamboo and tarpaulin. The toilets are temporary and life seems makeshift. Except, these camps began to come into being since 2011.

A makeshift kitchen inside a classroom at the Signature Bridge refugee camp.

| Photo Credit:

SUSHIL KUMAR VERMA

“Our relatives here became our visa guarantors and after months of savings, selling our animals and a prolonged wait for visas, we finally made the move only with a few clothes,” she says.

It has been 10 years now, but she has not been able to visit her parents in Pakistan yet. Choking on her words, she says that when people of her generation leave for India, they know that it is probably the last time they get to see their parents. “To save the community from becoming extinct the people in their 30s have been fleeing Pakistan since 2010,” she says.

While they crossed the border with starry eyes, Rama, 35, Kesari’s sister-in-law, says nothing has changed for them apart from one factor. “There we constantly feared being cornered for not following Islam. If anybody looted us, the police would not act. But apart from being surrounded mostly by Hindus here, what has changed?” she says. Pointing at kuccha roads in front of the cluster, she says the sewers are uncovered, there is dirt everywhere, flies swarm all around, and the youth have no jobs.” With an ironic smile, she says, “We were poor there; we are poor here; only now we belong to the majority.”

Arriving and staying

Joining her, Bhagwan Dass, a 45-year-old Pakistani Hindu in the same camp, says the idea of moving to India was not their fathers’. “Our grandfathers were the ones who saw the Partition, but neither they nor our fathers ever thought of moving to India. They had accepted their fate and despite being a religious minority knew that was their janmbhoomi (place of birth),” he says.

The community started thinking about immigrating when senior Hindu leaders from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) reached out to them in person, assuring them that as Hindus they belong in “Bharat”, he adds.

“The first lot that migrated to India first came by applying for the teerth visa (to visit Hindu religious sites like Haridwar and Mathura). They never went back. Gradually they became guarantors for the next lot of us. That is how our relatives from Sindh have been coming to India,” says Bhagwan, who farms for a living.

As he speaks, his voice fades as the volume of a news channel is raised in his neighbour’s courtyard. Sitting on a khatiya (bed made of rope and bamboo), the neighbour intently listens to the news anchor telling the world about the escalation of tensions between India and Pakistan. As the anchor announces the closing of the Indian air space for Pakistani aircraft and firing along the Indo-Pak Line of Control, more neighbours huddle around the khatiya in the courtyard which many homes have access to.

“In our world, we are accustomed to monthly visits to cyber cafes for visa renewals. We have made peace with it as long as nobody asks us to go back,” says Bhagwan, echoing Kesari’s fears about the safety of relatives in Pakistan.

Bhagwan recalls how in 2019, after the Pulwama attack, he was not sure if his sisters and parents were even alive. “For many days we did not hear from them because our calls were not getting through. We thought that the government there had hurt them, so we had started to accept that we would never hear their voices,” he says. He and the others at the camp refuse video bytes because they do not want to make relatives back in Pakistan vulnerable to attacks.

The cost of war mongering

In the camps across the Capital, the past week has been stressful as it has brought back difficult memories from the past, and the constant fear of technically being a “Pakistani” national despite having the current regime’s support. “Many here don’t have long-term visas. Some have applied and have not received it; some are yet to apply,” said Dharamveer Solanki, 55, a resident of the refugee camp at Majnu Ka Tila.

On April 28, the Delhi police asked the heads of these camps for a list of those who live there, with details of name, age, parents’ names, date of exit from Pakistan, passport and visa details. “In our camp, 181 residents have received their Indian citizenship but 81 are waiting to get it (out of a total of 300),” says Dharamveer, who came from Sindh too.

Hari Dass (left) from the Majnu Ka Tila camp.

| Photo Credit:

SUSHIL KUMAR VERMA

Residents of the camps say that they never felt like they were part of the mainstream in Pakistan. They didn’t send their children to school fearing conversation, there were no formal jobs available to them and most lived in poverty. “There too I did odd jobs, but we were often left without food some days,” says Satram, 40, who came to India two weeks ago. “But here, I can at least make ends meet. We don’t starve; we can eat at the gurudwara.” In Sindh too, Satram remembers sheltering in a local gurudwara.

Hari Dass, 45, runs a kachori-sabzi stall near Signature Bridge and does odd jobs like transporting goods or working as a farm labourer to support his brother in Pakistan, so his brother can join him in India. “Each person has to pay ₹50,000 as a bribe for a passport. Then, there’s the wait for the visa that can take up to a year. All the struggle will now go to waste,” he says.

Hari’s brother and his family reached the Wagah border with their permits a day after the attack and were told they could not cross over. “They were preparing to come to India and settle here, but they are not being allowed to cross over from Pakistan to India despite being Hindus,” he says, dejected.

Edited by Sunalini Mathew

Published – May 04, 2025 09:23 pm IST

Source:https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/moving-from-a-minority-to-a-majority/article69534351.ece