The latest class VII social science textbook published by the National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT), Exploring Society: India and Beyond (Part 1), has drawn criticism from educators and historians. Released under the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020-aligned curriculum, the textbook omits portions of the country’s medieval past.

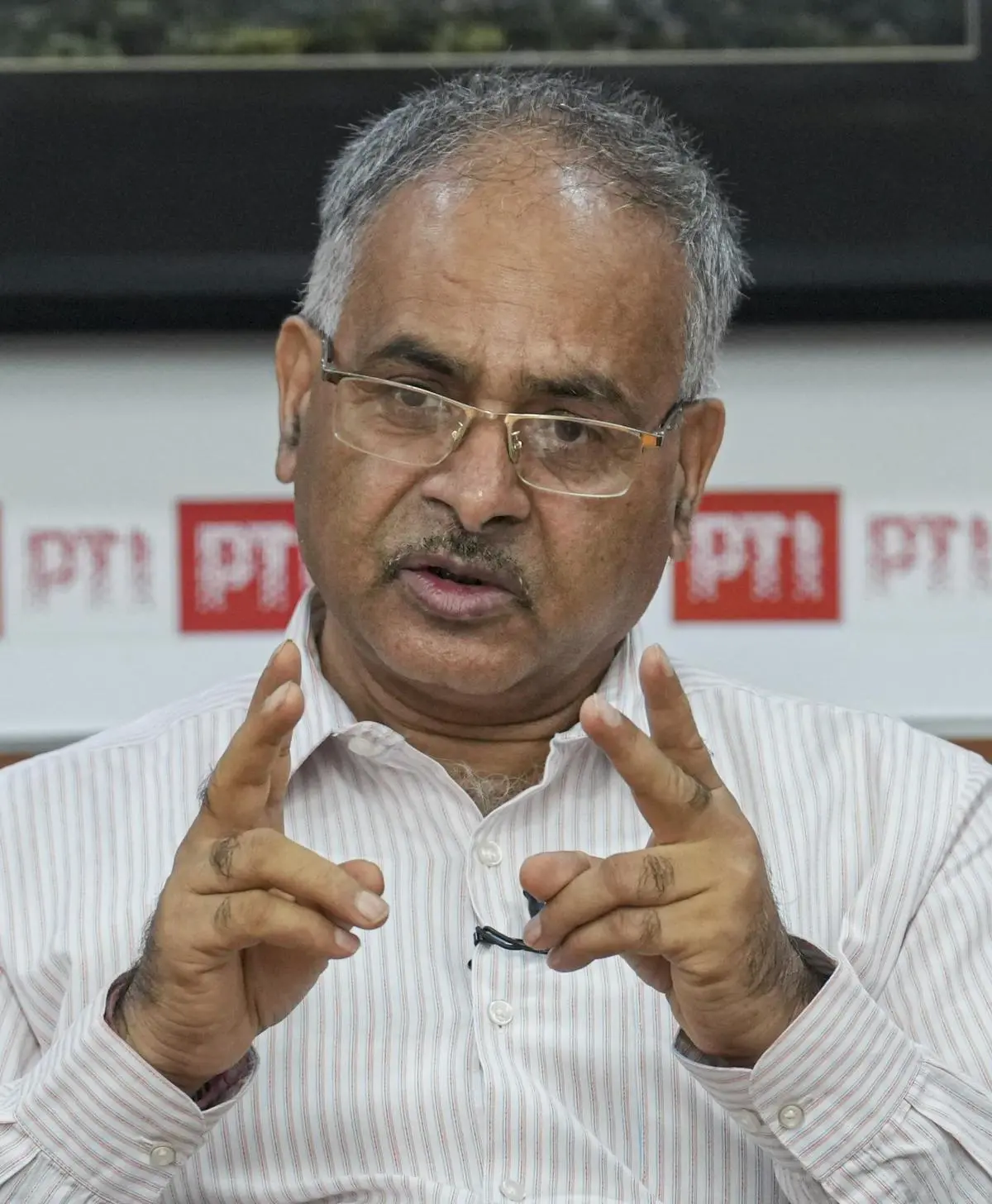

It also introduces content that blurs the line between mythology and historical fact. In the foreword, NCERT Director Dinesh Prasad Saklani frames the textbook as an attempt to promote education rooted in “Indian ethos and its civilizational accomplishments”.

The textbook is part of a broader curriculum overhaul under the new National Curriculum Framework for School Education (NCF-SE) 2023, a key component of NEP 2020. Following the revised textbooks for classes III and VI introduced last year, NCERT has now rolled out updates for classes IV and VII. The new class VII social science textbook merges history, geography, and civics into a single volume, replacing the earlier subject-wise structure. Yet it is the alleged selective erasure and rewriting of historical content that has stirred controversy.

Bypassing Delhi Sultanate and Mughals

Omitting nearly six centuries of medieval history, the textbook bypasses the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals, focussing instead on ancient India between 1900 BCE and 300 BCE. While the 2024–25 reprint of the earlier class VII textbook featured eight chapters covering the 7th to the 18th century, the new edition includes only four chapters, discussing ancient dynasties such as the Mauryas, Shungas, and Satavahanas, ending around the Gupta period. NCERT has announced a second volume to be released later this year, but has not clarified whether the excluded chapters will be reinstated.

For historians, the implications are far-reaching. “If it is indeed the case that the Sultanate and Mughal periods have been dropped entirely, it’s quite an absurd proposition,” said Mridula Mukherjee, the historian and former chairperson of the Centre for Historical Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “Continuity is essential to any historical narrative. Big gaps distort understanding. That’s not how history is written or taught.” She warned that excluding such formative periods disrupts the chronological flow and prevents students from grasping the evolution of Indian society, a core aspect of historical inquiry.

Also Read | Dinanath Batra: The ‘educationist’ who waged war against knowledge

Mukherjee also argued that these exclusions indicate a move to “minimise or invisibilise the role of Muslims in Indian history”. While NEP 2020 does not explicitly prescribe such changes, she said it creates a broad ideological framework—emphasising “indigenous traditions”—that textbook writers interpret in ways aligned with majoritarian politics. “The NEP may use lofty language about critical thinking, but what truly matters is what students read in classrooms.”

One chapter, “How the Land Becomes Sacred”, can be taken as an example of this ideological push, noted the educators. Beginning with a quote from the Bhagavata Purana, it presents India’s geography through pilgrimage routes, temple networks, and sacred Hindu spaces, without clearly distinguishing between mythology and historical fact. Although other religions are mentioned, the focus is overwhelmingly one-sided. The 2025 Kumbh Mela also features in this chapter.

“This is all part of the same trend,” Mukherjee said. “Much of mythology is now being treated as historical fact. Epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata are invaluable cultural texts, but they are not proven history. Students must be taught to evaluate sources—textual, archaeological, oral—critically.”

Increased use of Sanskrit

Bhupinder Chaudhary, a history professor at Maharaja Agrasen College, Delhi University, was more blunt: “Framing geography and history through sacred Hindu narratives without proper context is not just pedagogically flawed—it’s part of a deliberate ideological project.” According to him, the new textbooks flatten diversity and dissent, projecting a narrow, majoritarian vision of India’s past.

NCERT Director Dinesh Prasad Saklani during an interview in New Delhi on June 15, 2024. In the foreword to the latest class VII social science textbook, Saklani frames the textbook as an attempt to promote education rooted in “Indian ethos and its civilizational accomplishments”.

| Photo Credit:

Kamal Singh/PTI

Both Mukherjee and Chaudhary agree that epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata are important—when taught as reflections of societal values, not as literal history.

Another notable change is the textbook’s increased use of Sanskrit. It now includes pronunciation guides and teaches Roman-script transliteration using diacritical signs. Terms like kshetra (area), sutra, and janapada (tract of land) appear in the English edition, often with minimal explanation. “Sanskrit is not the language of all Hindus,” Chaudhary said. “Historically, it’s been a marker of upper-caste dominance. Its imposition through textbooks reinforces cultural hierarchies and undermines India’s linguistic diversity.”

He also pointed to another important aspect: “Despite being a dead language, Sanskrit is being aggressively promoted. All colleges under Delhi University, for example, were recently instructed to hold 20-day Sanskrit workshops for students.”

Rationale of ‘rationalisation’

Over the past several years, NCERT has repeatedly pruned the historical narrative in the name of “rationalisation”. This began during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the educators, with the stated aim of removing overlapping or irrelevant material. In practice, this led to the elimination of major segments on Islamic rule. In 2022, a two-page table on Mughal emperors was removed from the class VII textbook, and the “Kings and Chronicles” chapter on the Mughal courts was dropped from the class XII history syllabus. Sections on Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and post-Aurangzeb political fragmentation were cut from class VIII. By 2023, the Mughal era had been reduced to scattered mentions.

Mukherjee explained the pedagogical impact: “At an early age, you’re impressionable. If you erase the Sultanate and Mughals from class VII, there’s a real chance students will grow up without any knowledge of them.” She noted that the standard sequence—ancient history in class VI, medieval in class VII, and modern in Class VIII—meant students might never revisit these topics unless they opted for history in class XI or XII. “That’s deeply worrying.”

“This is not an isolated change in a textbook. This is a concerted, top-down agenda of rewriting history to fit a majoritarian political narrative.”Bhupinder ChaudharyHistory professor, Maharaja Agrasen College, Delhi University

Modern Indian history has not been spared either. In 2022 and 2023, chapters on the 2002 Gujarat riots, the 1975 Emergency, the Babri Masjid demolition, and Dalit and Naxalite movements were removed or diluted. References to Gandhi’s opposition to Hindu extremism and the ideological background of his assassin, Nathuram Godse, were edited out from class XII political science. In 2024, after the Supreme Court’s 2019 verdict, mentions of the Babri Masjid were deleted, with NCERT citing alignment with “recent developments”. Coverage of the Congress party’s decline post-1989 and the Mandal Commission was also reframed, casting the latter as a positive reform.

According to Chaudhary, this is a clear pattern. “Right-wing leaders, the RSS, and the BJP want to consolidate Hindus as a political bloc. Targeting the Mughals and Sultanate rulers helps create a simplified, unifying narrative.” He noted that Hindu society is inherently diverse and fragmented, and this historical revisionism is intended to forge cohesion through selective storytelling.

‘A majoritarian political narrative’

“This is not an isolated change in a textbook,” Chaudhary said. “This is a concerted, top-down agenda of rewriting history to fit a majoritarian political narrative.” He added that this ideological template is now applied across disciplines. “Curriculum changes in political science, philosophy, and literature have removed content on caste, Kashmir, Gaza—anything that clashes with right-wing views.” Faculty members, he said, have been coerced during Delhi University’s syllabus revision meetings to cut material on caste and conflict. “It’s like Orwell’s 1984. You hide the truth, erase complexity, and train students to think in only one direction.”

Chaudhary warned that the result will be ideologically conditioned minds, not informed citizens. “You can indoctrinate, but you can’t cultivate critical thinking this way.”

Also Read | The blackboard crisis

While NCERT is an autonomous central body and cannot enforce its textbooks on State boards, its content is widely adopted across the country, not just by CBSE-affiliated schools but also by many State boards that model their textbooks on NCERT materials. Although education falls under the Concurrent List of the Constitution and States are free to diverge, the ideological direction set by the Centre often influences local curricula, noted the experts.

Another emerging concern is the narrowing pool of contributors involved in writing these textbooks. Earlier editions were authored by eminent scholars from premier institutions. Today, much of the writing is handled internally by NCERT staff. “Earlier, you had historians like Romila Thapar and Satish Chandra,” Chaudhary said. “Now, it’s the faculty following instructions. These are not scholars working with academic rigour. A serious historian would never allow this kind of rewriting.”

“This isn’t just about history,” he concluded. “It’s about the kind of society we want to build. What we’re cultivating isn’t analysis—it’s loyalty. We’re not producing thinkers. We’re producing conformists.”

Frontline reached out to NCERT for comment but did not receive a response.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/education/ncert-textbook-controversy-medieval-history-omission-nep-2020/article69556504.ece