The Supreme Court’s judgment in early April laying down timelines for Governors and the President to act on Bills referred to them for their assent and its decision to use its extraordinary powers under Article 142 of the Constitution to declare that 10 Bills passed by the Tamil Nadu Assembly and pending with Governor R.N. Ravi were deemed to be assented have led to a huge political furore.

Members of the ruling BJP went hammer and tongs against the Supreme Court for its “judicial overreach”.

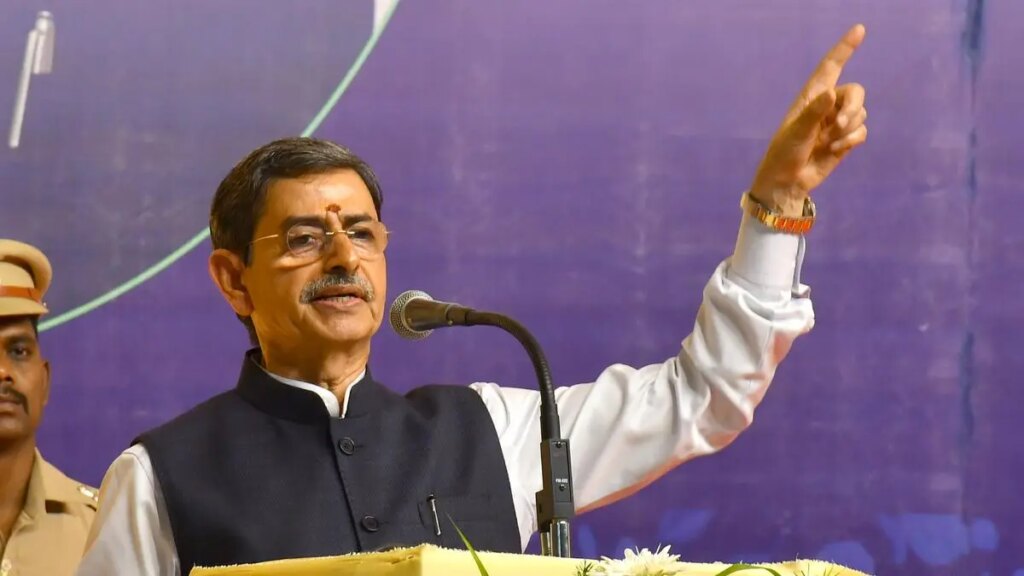

What raised eyebrows, however, was the sharp critique delivered by Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar. He remarked that the judges are legislating, performing executive functions, and acting as a “super Parliament”.

At the centre of the raging debate is the Supreme Court’s judgment passed on April 8 on a petition filed by the Tamil Nadu government against Governor Ravi’s inaction in discharging certain functions—most notably his withholding of assent to, and reservation for the President’s consideration, 10 Bills passed by the State Assembly. A two-judge bench of Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan pronounced its verdict in a 415-page order.

For and against

Away from the high-decibel attacks on the apex court, legal minds have argued both for and against its decision, with the former taking the position that the court had to be proactive while deciding the matter, and the latter fearing that the judiciary may have, in its intent to prevent misuse of power by the Governor, intruded into the legislative and executive domains, thereby setting a problematic precedent.

Also Read | Is Governor R.N. Ravi using constitutional office to challenge Tamil Nadu’s cultural autonomy?

In the judgment, Justices Pardiwala and Mahadevan went into the role of the Governor under Article 200 of the Constitution, which deals with the powers of the Governor with regard to grant of assent to Bills passed by the State Assembly, and said that the Governor does not hold the power to exercise “absolute veto” on any Bill.

The apex court also went into the manner in which the President, under Article 201 of the Constitution, is required to act once a Bill has been reserved for his or her consideration by the Governor. It set a time frame for the President to act in such a situation, also stating that the President “ought to” seek the court’s opinion under Article 143 for Bills reserved for his or her consideration on grounds of perceived unconstitutionality.

It said that the discharge of functions by the Governor or the President under Articles 200 and 201 was not beyond judicial review.

Passing 10 Bills

In another significant decision, the court exercised its powers under Article 142 of the Constitution to declare that 10 Bills that had been pending with the Tamil Nadu Governor were deemed to have been assented on the date they were presented to the Governor after being reconsidered by the State legislature, that is, on November 18, 2023.

Article 142 empowers the Supreme Court to pass any decree or order necessary for doing complete justice in any case or matter pending before it.

DMK leaders and supporters celebrating the apex court’s judgment, in Chennai on April 8.

| Photo Credit:

LAKSHMI/ANI

Govind Mathur, former Chief Justice of the Allahabad High Court, said that the criticism of the apex court that it had exceeded its jurisdiction in the Tamil Nadu case was “absolutely ill-founded and unwarranted, if not mischievous”.

He added that the Supreme Court, while examining the scope of Articles 200 and 201, also looked into its own authority to judicially review the action or inaction on part of the Governor or the President.

He said: “In the present scheme of things, the Governor may take any action with regard to a Bill forwarded to him or her to grant assent. But any decision that the Governor may take has to happen ‘as soon as possible’. It is true that Article 200 nowhere prescribes any time limit, but the term ‘as soon as possible’ reflects urgent action on part of the Governor.”

Referring to the political context in which the judgment came, experts pointed to growing Centre-State tensions, especially in States ruled by opposition parties, and the growing criticism that Governors were working as agents of the Centre. Given the prevailing political scenario across the country, the judgment is bound to have wider ramifications.

Expert opinion

Bishwajit Bhattacharyya, former Additional Solicitor General of India, said: “Article 156(1) of the Constitution stipulates that the Governor shall hold office during the pleasure of the President. President’s ‘pleasure’ can be withdrawn in a split second. ‘President’s pleasure’ means the decision of the Union Council of Ministers. With increasingly debased politics today, the post of Governor has degenerated into a political tool of the Centre.”

He added: “In my view, the apex court was constitutionally obligated to curb any arbitrary inaction of Governor, and to set a time limit. This cannot, by any means, amount to judicial overreach. Any consequential action by the President, therefore, cannot be beyond judicial scrutiny. The judgment is salutary and must be applauded.” There is, however, a view that laying down timelines, when the Constitution itself does not prescribe any, amounts to an overreach by the court.

The Supreme Court and Article 142

The apex court has invoked Article 142 in several matters. They include:

Ordering Union Carbide to pay $470 million to victims of the Bhopal gas tragedy

Banning liquor sales within 500 m of highways

Granting divorce in cases of irretrievable breakdown of marriage.

Vivek Narayan Sharma, a constitutional expert and advocate at the Supreme Court, said: “The judgment under discussion, by mandating fixed periods under Article 200 and Article 201, effectively supplements the Constitution, bypassing the mechanisms it prescribes. By judicially prescribing timelines, the court circumvented both parliamentary process and constitutional remedies, unsettling the delicate separation of powers.”

Sharma also argued that the court, by declaring that the Bills pending with the Tamil Nadu Governor were deemed to have been given assent to, had entered the domain of the executive. According to him, the President in her wisdom may have referred any of these Bills or all the Bills to the Supreme Court to seek its opinion under Article 143 of the Constitution, if it was felt that a question of law had arisen or was likely to arise, which is of such a nature and of such public importance that it is expedient to obtain the opinion of the apex court on it.

“This [Supreme Court’s decision on the pending Bills] is a very serious breach of the constitutional right of the President by the Supreme Court. By invoking Article 142 to declare that 10 Bills ‘shall be deemed to have become law’ from the date of their presentation, the Supreme Court bypassed this constitutional requirement and assumed a function reserved for the executive. This amounts to judicial legislation, a practice the court itself has consistently disapproved of.”

Constitution and evolution

On the question of rewriting of the Constitution, Justice Mathur said the document was not static and that it has evolved over time to meet the changing needs and aspirations of society. He also said that it was wrong to say that the Supreme Court was acting like a “super parliament”.

He said: “The statement that the Supreme Court is acting like a super Parliament is misconceived. The Supreme Court is the custodian of our Constitution. No one, including the President of India, Governor of any State, or even the Supreme Court are above the Constitution. If anyone acts or doesn’t act as per the Constitution, the Supreme Court should judicially review such action or non-action to ensure supremacy of the Constitution. In the Tamil Nadu case, the apex court has done that only.”

On the question of whether prescribing timelines would amount to rewriting the Constitution, the court ruled: “Prescription of a general time-limit by this Court, within which the ordinary exercise of power by the Governor under Article 200 must take place, is not the same thing as amending the text of the Constitution to read in a time-limit which would fundamentally change the procedure and mechanism stipulated by Article 200.”

Court ruling and explanation

The court said that in laying down the time limit, it was guided by the inherent expedient nature of the procedure prescribed under Article 200.

With regard to the court’s decision on the pending Bills, Bhattacharyya pointed to the “peculiar facts of undue delay caused by the Tamil Nadu Governor pertaining to Bills referred to him”. He added: “The Supreme Court held that the Tamil Nadu Governor acted with clear ‘lack of bona fides’.”

Also Read | The curious farce of R.N. Ravi

Explaining its decision on the 10 Bills, the court said in its judgment: “The conduct exhibited on part of the Governor, as it clearly appears from the events that have transpired even during the course of the present litigation, has been lacking in bona fides. There have been clear instances where the Governor has failed in showing due deference and respect to the judgments and directions of this Court. In such a situation, it is difficult for us to repose our trust and remand the matter to the Governor with a direction to dispose of the bills in accordance with the observations made by us in this judgment.”

Meanwhile, legal experts have stressed that while the judgment raises many points that can be critiqued and debated, the reactions can only be described as judiciary bashing.

Justice Mathur said: “The most unfortunate part is that certain persons, while criticising the judgment, have lost their objectivity. A judgment is always open for objective criticism, but in this case, some of the critics, instead of criticising the judgment, are levelling allegations upon the judges and searching motives. This is not only contemptuous but against constitutional morals.”

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/politics/supreme-court-article-142-tamil-nadu-governor-ruling/article69504441.ece