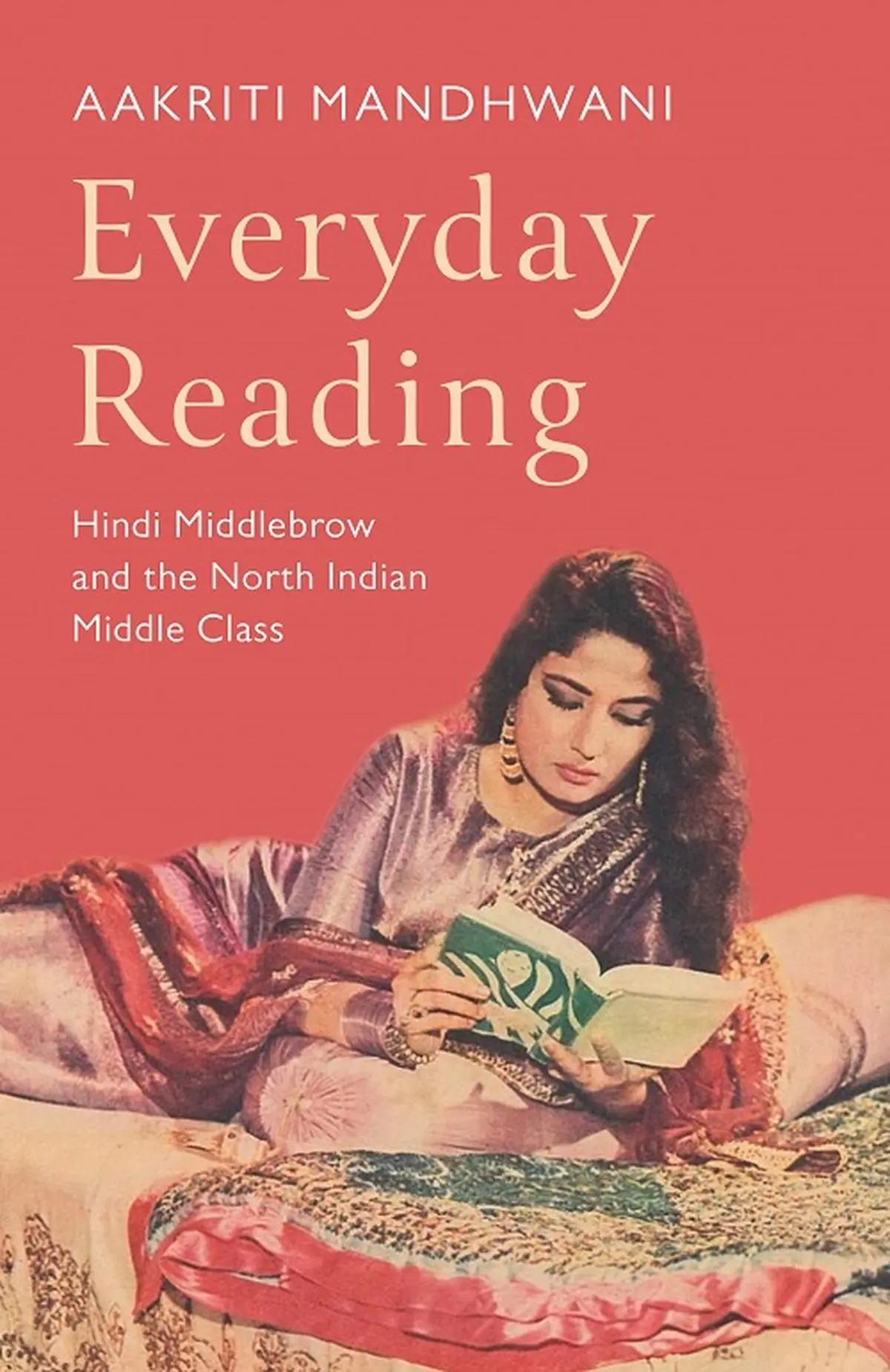

When a beguiling, vintage photograph of a lost-in-a-book Meena Kumari features on a book cover, one expects pleasure, even from an academic study investigating reading for pleasure. Everyday Reading by Aakriti Mandhwani sparked magazine-reading memories of my younger days. Print culture was the big game changer of the 1920s, much like AI today. By the 1940s, cheaply priced mass magazines (in all major Indian languages) were shaping the ways in which the reading classes imagined themselves. This book is a spirited study of the lively mid-20th century “popular” Hindi print cultures and the public sphere they created.

To “understand and reimagine the (reading) middle classes”, Mandhwani categorises the magazines into middlebrow and lowbrow. The middlebrow is seen as something synonymous with Sarita: wholesome, educational, popular but not literary, a magazine that has something for the whole family, and which features aspirational narratives to the exclusion of narratives on poverty and unemployment.

Everyday Reading

Hindi Middlebrow and the North Indian Middle Class

By Aakriti Mandhwani

Speaking Tiger

Pages: 242

Price: Rs.599

Lowbrow, on the other hand, denotes magazines that carried “genre fictions and provided an alternative to the aspirational and consumption aesthetic of middlebrow”. They focussed on the sensational and the thrilling and not so much on building a dedicated readership through interactive advice columns, readers’ letters, readers’ contributions, and so on.

To understand the “emergence, nature and concerns” of the Hindi-reading middle classes, Chapter 1 of the book sets up the magazine Sarita as the undisputed pioneer of the middlebrow. Chapter 2 focusses on a “dilchasp” (engaging) study of the very affordable Hind Pocket Books that published everything: from Ghalib to Gitanjali to Gulshan Nanda. Chapter 3 is a detailed study of Dharmyug, the Hindi weekly edited by Dharmvir Bharti. Chapter 4 studies what are called the “lowbrow” magazines, Maya (Magic), Manohar Kahaniyaan (pleasing stories), and Raseeli Kahaniyaan (juicy stories).

The problem is, what we take as highbrow literature today (writings by Dharmvir Bharti, Agyeya, Kamleshwar, Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi, Amritlal Nagar) took birth as popular literature back then. Hence, the semiotics of middlebrow and lowbrow, no matter how the author situates them, tends to become fuzzy as the publications are analysed. The arbitrary focus on Sarita and Dharmyug—from a bouquet of successful magazines like Kadambini, Saptahik Hindustan (whose cartoon “Musibat hai” was as popular as Abid Surti’s “Dabooji” in Dharmyug), Sarika, Dinaman, Saraswati—is not explained. If one does not get bogged down in categories, the real delight of the book lies in its meticulous endnotes, which challenge the research question(s) and complicate easy conclusions.

Also Read | How deep reading helps us resist fundamentalist thinking

But some context first.

I grew up in a television-free world of the 1970s, steeped in the magazine-reading culture of the day. My mother was an avid magazine reader with a collection of kahani visheshanks (fiction special issues) and prem-katha visheshanks (romance special issues) of the 1960s magazines. These visheshanks featured stories by Amritlal Nagar, Phanishwar Nath Renu, Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi.

To maximise value-for-money, our hard-up, small-town parents relied on lending libraries organised by the news vendor who knew that while magazines were many, pockets were small. Everyone in our neighbourhood bought one magazine and read three more of their choice by paying a small extra charge for a two-day rental. The chawani-mein-char (four old magazines for 25 paise) libraries, too, did brisk business.

The dates—which magazine came on which day—were marked on the wall calendar. We waited for our first copies. The whiff of ink on page, the feverish turning, the equal desire to linger, the paper between fingers. What remains in memory is the gigantic sense of anticipation that fuelled our urgency to read. One had to finish reading with delicate care and without crumpling the pages so that the magazine could be passed on to the next person.

That Kamleshwar, Mohan Rakesh, Mannu Bhandari, Ravinder Kalia were writing in them, that Renu and Nagar were showcased in special editions, that we were reading Bengali greats like Sarat Chandra or Sankar in Hindi translation—all this was completely lost on us. The satire columns penned by Sharad Joshi and Shrilal Shukla were regularly read out aloud, though only for the laughs generated. We read firmly for pleasure, but along with the tacky, a lot of “highbrow” literature by today’s definition was regularly slipping into us.

No one we knew was devoted to only one magazine, which is not a comment on the calibre of magazines like Sarita and Dharmyug. The notion that each magazine had its exclusive reading public defined by circulation figures, which it catered to, is a late 20th century one. Until the 1970s, everyone borrowed, shared, maximised. On trains, one magazine could do the rounds of an entire compartment in a 24-hour period.

Covers of Maya

The thing is, there was so little to consume and even less money. The radio was nightly, the movies occasional, the imported books and comics beyond buying. The paucity of other easily consumed entertainment was the necessary precondition that made mass magazines so attractive. The magazines were always accessible in newer editions via doorstep lending libraries. More than aspiration for things, they fed our imagination. The defining motivation was to imagine and experience new worlds. We were consuming ideas.

And while my view might be just my view, here is Mrinal Pande, who says in her book The Journey of Hindi Language Journalism in India: From Raj to Swaraj and Beyond (2022) that popular periodicals like Dharmyug and Saptahik Hindustan experienced “a renaissance moment post Emergency” with peak circulations, literary greats as editors, featuring dialects and bolis, translating and getting translated.

Coming back to Mandhwani’s categories, I wondered, could I have been consumerist and aspirational when reading Sarita and someone opposite when reading Maya? If the sober Sarita and swashbuckling Dharmyug both constituted the middlebrow, where did Sarika, Dinaman, Saptahik, and Kadambini fit in? How large was the middle? What were we when we were reading Renu’s stories set in rural milieus in Saptahik Hindustan? Did we become as many selves as the magazines we consumed?

Maybe that is why Mandhwani, after defining middlebrow in consumerist-aspirational terms, and realising the contradictions, says at the end of Chapter 2: “The impetus of middlebrow was not just on pleasure or aspirational improvement or subscription to taste; it also lay, as mentioned above, in the need to know.” In a similar vein, she states that “while all middlebrow readers were middle class, all middle-class readers were not necessarily middlebrow and could be reading lowbrow and highbrow publications”.

That is correct.

The magazine “brows” can self-define the widely different magazines but not the writers who wrote for them, or the class or taste or variety of the reader. The more Mandhwani delves into this time-machine-like world locked away in yellowing crumbling paper in yellowing crumbling libraries, she discovers evidence of shifting readerships and fluid writerships.

The chapter on Sarita posits that the mid-century magazine readers were prioritising the everyday, easy-to-read magazine compared with the more literary type of magazine. However, the same chapter also mentions that stalwarts of the Nayi Kahani (new story) movement like Mohan Rakesh and Rajendra Yadav were writing for Sarita. The endnotes of the same chapter reveal that writers like Usha Priyamvada were also writing stories for Sarita though only under an abbreviated, anonymous sounding “Usha”.

Sarita’s reader is posited as an “assertive female reader” seeking space and individuality, but the endnotes reveal that didactic articles upholding the joint family and collective values also featured alongside those championing more individualistic values. Maybe the very contradiction of upholding the old while celebrating the new created space for imagining and articulating individuality?

Everyday Reading by Aakriti Mandhwani is a spirited study of the lively mid-20th century “popular” Hindi print cultures and the public sphere they created.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

Although these magazines favoured the simpler, dialect-laced “non-normative” Hindustani over the official Sankritised Hindi, they were also primarily Hindu spaces, carrying pictures and motifs of Hinduism. I remember Holi and Diwali visheshanks but never saw an Eid visheshank.

The most delightful tidbits are about literary giants who, when not writing for the magazines, were editing them. Agyeya categorises the Hindi reader (pathak) thus: those concerned with spiritual welfare, those who think magazines are for women, those looking for entertainment, those who seek to purify Hindi, and, finally, the Progressive type, whom he holds in disdain. There is the bit about Rajendra Yadav calling D.N. Malhotra of Hind Pocket Books, insisting that he drop Mannu Bhandari as their author. Malhotra dropped Yadav instead and retained Bhandari.

The chapter on lowbrow magazines initially defines lowbrow in terms of non-aspirational genre fiction that provided romanch (hair-curling thrills). However, category problems crop up immediately. Mandhwani gives a delightful overview of Manto’s powerful story about the lack of privacy in Mumbai chawls titled “Nangi Awazein” (Naked voices) published in Maya in 1952. The same year, Maya also published Upendranath Ashk’s “Paap ka arambh” (The beginning of sin). It seems, in the 1950s, the words “naked” and “sin” in the title and a proletarian plot could guarantee lowbrow status to a gem of a story. Maybe that is why, relinquishing lowbrow categorisation by nature and subject matter, Mandhwani clarifies that the lowbrow was characterised by poor paper and production quality.

Also Read | Celebrating 300 editions: Kalachuvadu marks a historic milestone in India’s literary journalism

Mandhwani acknowledges that all attempts to categorise the wild beast of mid-century popular magazines end in overlap. Yet Sarita and Dharmyug comprise “the consecrated middlebrow, central to fashioning of class identity”. The middlebrow magazines and the reading middle classes they created come across more as a surging Sangam fed by shifting streams.

The questions generated by the book set the ground for further research. When we talk of middle-class reading culture, can we afford to overlook the failed, the short-lived, the shut-down, the magazines we do not even remember, not to speak of their 1920s precursors—all of which together constituted the middle-class-making, public opinion-generating, taste-setting, politics-making culture?

Varsha Tiwary is a Delhi-based writer and translator of 1990 Aramganj, a translation of the Hindi novel Rambhakt Rangbaz.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/books/middle-class-hindi-magazines-everyday-reading-book-review/article69494054.ece