Reading Viyyukka (TheMorningStar), an anthology of testimonial stories written by Maoist women revolutionaries, amid news of surrenders and encounter killings, is unsettling, to say the least. How do we totalise the relations between participant literature and politics at a time when facts and figures confirm the decisive waning, if not routing, of that politics? Undoubtedly, the inclusion of G. Renuka, who died in a staged encounter on March 31, 2025, or Narmada Akka, who died of terminal illness under incarceration in 2022, or Karuna, who is remembered for her exceptional courage, enhances Viyyukka’sappeal because it shows that Maoist women leaders were and are adept in wielding the gun and the pen alike. But names apart, do the 20-odd stories proffer new modes of thinking about contemporary women’s writings or do they remain grounded within the politics that inspired them?

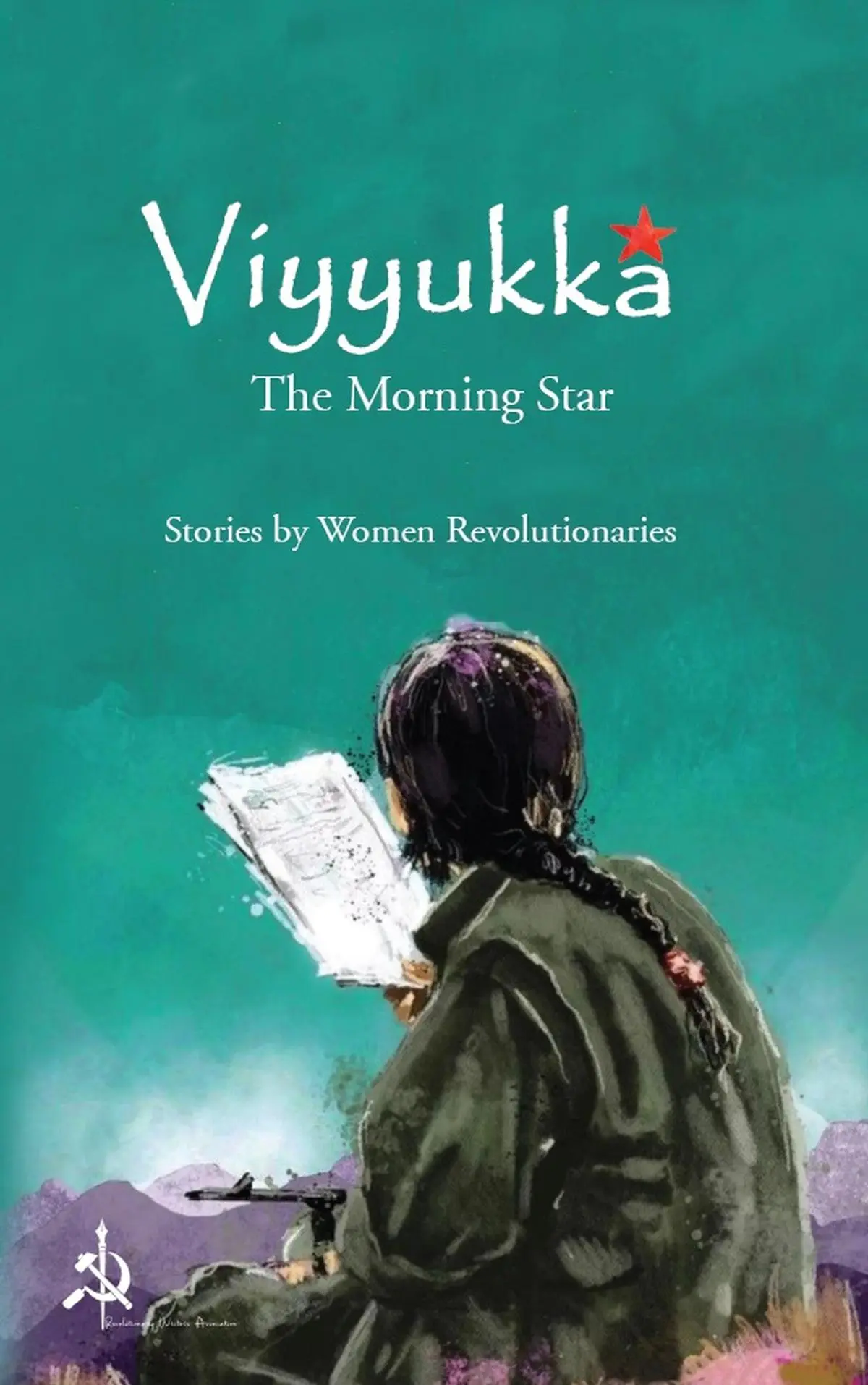

Viyyukka: The Morning Star

Stories by Women Revolutionaries

Edited by P. Aravinda and B. Anuradha

Revolutionary Writers Association, 2024

Pages: 270

Price: Rs. 350

Interestingly, Viyyukka represents only a small stratum of a larger body of 316 stories written by 52 authors, compiled over the years by P. Aravinda and B. Anuradha and published in 6 volumes. The first 146 stories, conceptualised under the category “revolution”, were published in three volumes in Telugu in 2023, in Vasanthamegham, the web magazine of Virasam (Revolutionary Writers Association). Admittedly, theEnglish anthology does not offer an extensive range, but another two dozen translated stories are available in the web magazine. Given the scope of the entire corpus, the present anthology holds an important promise of forthcoming English volumes.

Reading Viyyukka makes one wonder at the creative energies of women revolutionaries. Looking back in history, it is difficult to find such a corpus within the field of revolutionary women’s writing from the 1940s onwards. Unlike testimonies gathered by feminist scholars, Viyyukka writers record and write their experiences from the battleground, such as in “Encounter” or “Why I Became a Guerrilla”, an account of an Adivasi woman translated by her comrade.

Also Read | ‘Paramilitary forces dance after killing Adivasis’: Soni Sori

Where does this confidence in writing and translation come from? An obvious answer lies in the tremendous surge in women’s participation in the Maoist movement, especially over the last two decades. The simultaneous proliferation of women’s journals and organisations testify to this phenomenon. Importantly, this spectacular rise in women’s participation is intertwined with another expanding history, that of Maoist literature disseminated through vanguard collectives and collections. Hence, within this revolutionary cultural history, Viyyukka’s importance lies in foregrounding women’s voices.

Not only political propaganda

It can well be argued that Viyyukka reproduces the Maoist doctrinal ideology as the didactic aim is undeniable in stories which are tilted “Forward March of History” or “Famine Raid”, or “Red Flag”, or “People are the Bulwark”. However, before political propaganda is inferred as the sole purpose, it should be noted that there are specific female-centric nuances in stories such as “Diku” or “Bali” which affirm the empowering presence of the movement in Adivasi women’s lives. Similarly, stories such as “Marriage” explore women guerrilla lives and their right to decide whether they wish to marry or not.

Narmada, who wrote under the pseudonym “Nitya”.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

Significantly, the anthologyasserts that women’s writings are not only about women’s choices. For instance, in “Punishment”, two men are punished by a village panchayat for joining the Salwa Judum and for unleashing violence on villagers. However, instead of accepting the punishment, the duo seeks approval of the villagers by beheading the rapacious landlord who had enticed them into joining the Judum. While the panchayat celebrates this action, the squad leader is not impressed as he regards this personal act of vengeance as a failure of the panchayat’s workings. He argues that the panchayat could have collectively corrected the duo’s mistake of joining the Judum instead of imposing a coercive punishment on them. He argues that collective anger and not personal acts of revenge could have been the appropriate answer for the cruel landlord. The story ends with him urging the members of the Janatana Sarkar to “discuss crime and punishment comprehensively”. Through its depiction of the limitations of individuals and of institutions, G. Renuka’s story (written under the pseudonym ‘Midko’, a Gondi word for firefly), exceeds the common view of Maoism as a rigid and brutal philosophy of social change.

Foregrounding the female guerrilla imaginary

Through its diverse tales, Viyyukka foregrounds the significance of the female guerrilla imaginary. While exceptional women guerrillas such as “Ramko” are celebrated through a depiction of their heroic life and death, female comradeship is shown as crucial for the survival of two squad members during their harrowing interrogation and incarceration in “Story of an Arrest”. And, though not dominant in “Punishment”, the female friendship between two unlikely women, the oppressor’s wife and an oppressed woman, is important as this subtle friendship endorses a collective spirit which eschews the violence and hostilities inscribed in the punishment pronounced by the male-centric village order.

“The underground in “Viyyukka” is neither mythic nor hidden but is based on real people in Dandakaranya, the Nallamala and Palnadu tracts of Andhra Pradesh, the Andhra-Odisha border, the north and south Telangana regions, and parts of Jharkhand. Framed both by time and space, the testimonies of daily struggles highlight the significance of resistance that has grown in these areas. ”

Of course, the inevitable centre-margin binary is reproduced in stories such as “Why I became a guerrilla”, where the mother of a female guerrilla lingers in the background and unhappily watches the revolutionary father induct his daughters into the path of armed struggle. The female guerrilla does not engage with her mother’s concerns as she is inspired by the father. Consequently, the mother remains shadowy and participates only as a choric voice of support.

But elsewhere, in acts of grief, motherhood rises to its heroically powerful self. In “She is my daughter”, an old Adivasi woman falsely proclaims before the police that the deceased guerrilla is her daughter so that the latter can be honoured in death, something which her family would not have done. In “Three Mothers”, the challenge is whether the deceased youth will be recognised and honoured by his family especially since his biological and adopted mothers fear coming to the city mortuary. To overcome the family’s fears, an elderly female activist claims him as her son before the police. And yet, not only the two mothers—the one who bore him and the other who nurtured him—but also the ‘friend’ mother come together in their grief over his martyrdom.

Unheard voices

Viyyukka gathers unheard voices, and the editors remind that the early stories were written by the educated cadres who “went into the revolutionary movement from the plains and took to underground life”. To the world outside, the underground evokes ideas of subterranean stockpiles and incognito lives of wanted criminals. But the underground in Viyyukka is neither mythic nor hidden but is place-bound and is based on real people in Dandakaranya, the Nallamala and Palnadu tracts of Andhra Pradesh, the Andhra-Odisha border, the north and south Telangana regions, and parts of Jharkhand. Framed both by time and space, the testimonies of daily struggles highlight the significance of resistance that has grown in these areas. The interplay of languages in the stories—Telugu, Koya, Kuvvi, Marathi, and Hindi—foreground the promises and challenges of integration and preservation of Adivasi culture within Maoist cultural historiography.

Reading Viyyukka makes one wonder at the creative energies of women revolutionaries.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

At the end of each story, the editorial note provides information on the date and place of publication. The Preface, however, states that because of the uncertainties of guerrilla life, the date of publication does not indicate the actual time of writing. But who are these writers?

In “Women Revolutionaries”, B. Anuradha tells us that Shaheeda had authored as many as 32 stories, and her published anthology, Jaijipula Parimalam (The Fragrance of Jasmine), shows that she wrote under several pseudonyms such as “P. Seshulatha”, “N.D.”, “Mani”, “Prabhata” and even “Sudhakar”. Historically, women writers have tended to remain incognito because of the “habitual socio economic neglect of women”, a point stressed by the noted literary critic, Katyayani Vidmahe, in her review of one of the Telugu volumes of Viyyukka (self-translation).

Also Read | Editor’s Note: Dead end deadline

It is curious to reflect on how these women guerrilla writers have rekindled the age-old issue of anonymity underlying women’s writings, albeit for the political reason of protecting real identities, a praxis evident in Narmada’s usage of her pseudonym “Nitya” or in Karuna’s adoption of her literary name “Vijayalakshmi”. Likewise, while her writings affirm that Renuka was the proverbial firefly, Midko, Anuradha notes in “Women Revolutionaries” that she wrote under various pseudonyms such as Nirmala, Zameen, and Shwetha in her compilation, Metla Meeda (On the Steps). In short, while resurrecting the old debate over female authorship, the Viyyukka pseudonyms invigorate newer discussions on the relationship between political power and the female pen in contemporary times.

Viyyukka is an important intervention in the field of women’s political writing as its testimonial writings hold the promise of social change.

Sharmila Purkayastha is an independent researcher based in Delhi.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/books/viyyukka-maoist-women-revolutionaries-anthology/article69521500.ece