“It is only fitting that translations, like so much else, should reflect the times in which they are made,” Arshia Sattar concludes in her essay “Translation In English”, where she traces the long history of calls for the translation of Indian languages into English, beginning with William Jones’ Sacontala and Charles Wilkins’ The Bhagvet Geeta in the late 18th century—relics of an instrumental interest in a culture, where the Governor General encouraged traders and administrators to press up against and overhear Indian languages and customs. To learn in order to, later, possess.

This line of translation curved uneasily through the 19th century—when local knowledge became the arsenal in the growing British empire—with Indian attempts at representing oneself, albeit through the eyes of the British, and later, in a forceful decolonised context, at questioning the cannon, with even A.K. Ramanujan, who was belting out translations from Kannada and Tamil from his throne at the University of Chicago, being accused of perpetuating Oriental stereotypes. The question of what you are producing literature for gets twisted to what is the framework within which this literature is being produced.

Now, Sattar notes, there is “a shift towards translating primarily for Indian audiences”, a shift which involves leaving common Indian words untranslated. This is “partly because it is assumed that Indian readers will understand them and partly because the attempt is to carry a little of the flavor and rhythm of the original”, and partly, in an international context, because we believe that to explain yourself is to concede that your culture lurks on the periphery, a periphery that hopes to be spotlit by the centre.

There is a literary arrogance in leaving things unexplained, a pleasure in investigation, a confidence that the surf of sentence will tide over any ambiguity. Compelling writers work with both this arrogance and confidence.

Also Read | I started writing to challenge patriarchy: Banu Mushtaq

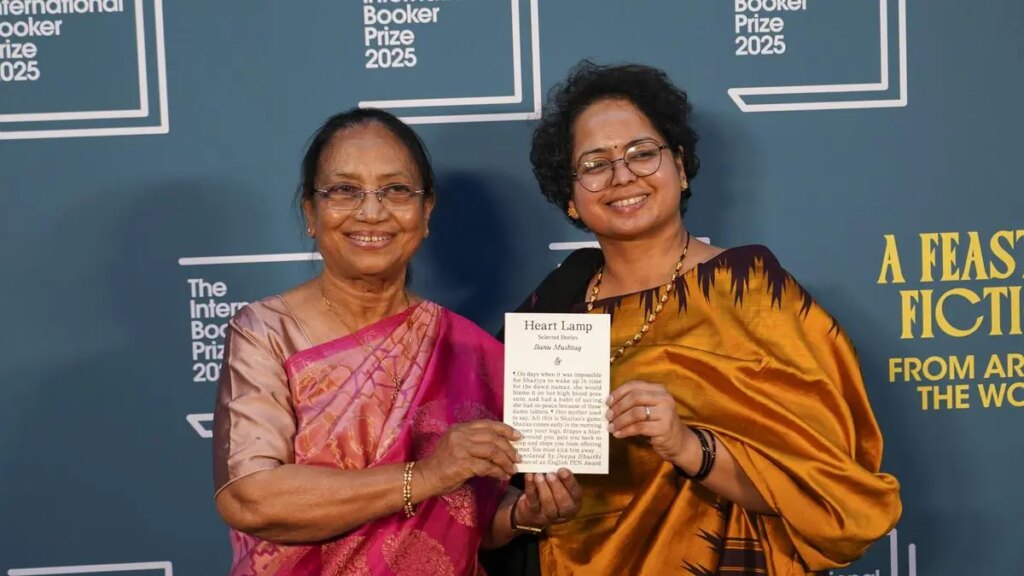

When Deepa Bhasthi, the translator of Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp—a collection of 12 shapeless short stories, cutting, abrupt, and meandering, originally written in Kannada between 1990 and 2023—which became the second Indian prose work to win the International Booker Prize, keeps words like “seragu” and “mutawalli saheb” untranslated in the text, she concedes how words might not have equivalences across languages, and that translating should not be burdened by the act of explanation. How can she keep referring to seragu as “the edge of the sari” when her female characters constantly slip their seragus over their heads? Similarly, how to clarify the specific duty of a mutawalli, who is the trustee of a waqf, which itself is a word that might demand an explanation.

Bhasthi’s choice is one of choosing clarity but not being burdened by it. This might be what a judge of the prize referred to when he called this text “a radical translation which ruffles language, to create new textures in a plurality of Englishes”. Plurality is built into the foundation of this text. Watching Girish Kasaravalli’s Hasina, which is based on one of the stories, is to feel multiple languages clamour together as one language—Hindi/Urdu, Tamil/Kannada, like watching languages, some familiar, others strangers, collide.

Ethics and aesthetics of italics

Another important choice is to abandon italics while referring to words not in the English thesaurus—the bane of writers working with more than English in their heads and homes. In my own book, I tried arguing for its removal, simply to be told that it was one of the house rules of my publisher—Penguin Random House. (Which also published Heart Lamp, so, perhaps, I had not argued enough, or for longer, or written an afterword about its politics.) Elsewhere, another publishing house which does not use italics—Aleph—was convinced by the late art historian Dr B.N. Goswamy to keep using it for his book, simply because that is a convention that saw him through decades of academic writing and columns where he introduced the world to a possible Indian way of seeing.

To read the italics as a concession to the Anglophone centre might, then, see Goswamy’s insistence as irony. An Indian way of seeing—by slanting our words?

In the afterword essay “Against Italics”, Bhasthi makes a clean but, perhaps, hasty submission, that the refusal to use italics is because “italics serve[s] to not only distract visually, but … announce words as imported from another language, exoticizing them and keeping them alien to English. By not italicizing them, I hope the reader can come to these words without interference…” Ditto for footnotes.

Also Read | Banu Mushtaq: The rebel writer

True, there is something fragile about reading the big Indian Anglophone novels—reading Aravind Adiga italicise paan, reading Anita Desai’s footnote about what paan is: “heart-shaped betel leaf smeared with lime paste, shredded areca nuts, cardamom, aniseed, folded into a cone and eaten”. Ready reminders of what the norms of knowledge and language are, and where you stand with respect to it. To come across a word italicised is a signal—it is okay to not know what this means, it is a specific cultural artefact that hasn’t been roped into the “universal” lexicon. We walk into literatures with broadly our sense of the world and lack thereof, and every sentence spotlights the limits of what we find familiar, what we do not yet know, what we need not yet know.

But there is also a danger of over-stating the meaning of a signal. Italics is to formatting what English is to language—they are, primarily, form. Much like writing in English is not necessarily an act of colonisation, although it comes from the history of colonisation, italicising words is not necessarily an act of exoticisation though it comes from the history of exoticisation. It is not the italics that exoticises but how we use it to write that exoticises the text. We must prise apart italics as an ethic from italics as an aesthetic. When, for example, bell hooks decided to not capitalise the first letters of her name because she wanted people to focus on her books, not on “who I am”, she was forcing an ethics into an aesthetic. That clearly did not work. We still care, and care even more now, for who she is, alongside what she said.

Convention and ideology

Bhasthi does not have patience for these kinds of complexities. In her essay, she is quick to mistake form for function—so the familiar “saheb” or “bhai” for someone who might not be a brother, used as a suffix, is seen not just as a mark of respect but as a means to “bring them into a circle of closeness by building these relationships … taking the edge off foreign ideas like individualism and personal identity”. Calling our teachers sirs and madams in school—conventions that are bored into our brains—does not mean we respect them. A convention is a habit. It is not an ideology. The difference between the two is one of agency and conscious practice. Language might be produced by an intentional thrust, but by being repeated over generations, flattened on the rocks of time, like cloth being whipped clean, it loses its intention. Sometimes, this intention itself might be shaky, unrealised, or even untrue. Words get decontextualised from their roots so easily, the act of rooting it feels both futile and excessive.

Especially coming at the end of a collection that cruelly breaks apart these half-formed ideas of the collective, of family, of the threadbare possibility of community within these throttling institutions—of faith, of marriage, of family—it feels odd to see language being read so literally, so forcefully.

Prathyush Parasuraman is a writer and critic who writes across publications, both print and online.

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/columns/heart-lamp-banu-mushtaq-indian-literature-translation-decolonising-english-deepa-bhasthi/article69629920.ece