On May 23, the world lost one of the greatest image-makers ever with the passing of the Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado. He was 81 years old and had been unwell with the consequences of a rare type of malaria contracted in Indonesia in 2010. Known for his majestic black-and-white photographs that frame the everyday and the ordinary in an extraordinary light, Salgado’s subjects were the often ignored and the dispossessed—those who, at once, form the global majority and are the least favoured politically and economically. Salgado leaves behind a unique and vast legacy of photographs that span the world, framing often unseen or unrecognised realities that are as much social as they are environmental.

In his lifetime, he won every major award in photography; his work straddles art and documentary through his luminous visual style, exceeding any attempt to categorise him as a humanist, an activist, an environmentalist or even as a photo-documentarian from the Global South. In the course of five decades, Salgado gave his life over to photography, placing it, as none had done before and with a panoramic scope that may never occur again, in the service of human and planetary dignity. In so doing, he raised photography to new visionary heights.

Born in the town of Aimorés, in Minas Gerais, Brazil in 1944, Salgado was the son of a land-owning family of cattle ranchers. If photography was his life passion, then his vision was crucially informed by his knowledge of economics, a subject in which he obtained BA and Masters degrees from São Paolo University. Together with his wife Lélia Wanick, whom he had met when she was only 17 years of age, Salgado took the decision, in 1969, to leave Brazil and seek exile from the military dictatorship in power there at the time by commencing doctoral studies at the University of Paris. In 1971, the young couple moved to London, where Salgado took up a post as an economist working for the International Coffee Organization.

Awakening social awareness

It was whilst he was in this job that he travelled to Africa, taking with him his wife’s camera in what would prove to be a life-changing move. He returned with a newly kindled awareness of the stark inequalities between international coffee prices set in the power houses of Western capitals, such as London, and the meagre income of the coffee plantation workers whom he had met in Africa, as well as of the power of photography to awaken social awareness in a way that no economically informed report ever would.

Also Read | Valmik Thapar (1952-2025): A force for nature

Shortly thereafter, Salgado took the decision to abandon his well-paid job and venture freelance into the realm of photographic documentary. Initially, he joined Sygma, a new photo agency, moving from there to Gamma in 1975 and, then, in 1979, to the prestigious agency Magnum. In the course of the next decade and a half, Salgado established himself as a leading photojournalist through images that still dwell in public memory, such as the assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan in 1981 and the burning of oil wells in Kuwait in 1991.

In 1994, following a disagreement with Magnum, he and Lélia started up their own photographic agency Amazonas Images in Paris. By then, it was evident that his creative energies were invested less in photographing specific events and much more so in the long photo essays that would define his life and legacy—“Other Americas”(1986), “Sahel: The End of the Road”(first published in France and Spain, 1986), “Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age”(1993), “Terra: Struggle of the Landless” (1997), “Migrations”(2000) and “The Children”(2000), and “Genesis”(2013). These were his personal endeavours, rendered public through repeated editions of his many books and exhibitions often curated by Lélia.

Salgado’s archive of images is so immense that over 30 collections have ensued and many more may continue to emerge posthumously. Several are thematic, such as “Africa”(2007) or “L’homme et l’eau”(Man and Water, 2005), while others include collaborations with visual artists, writers and photographers from the Global South, such Raghu Rai from India (“An Uncertain Grace”, 1999).

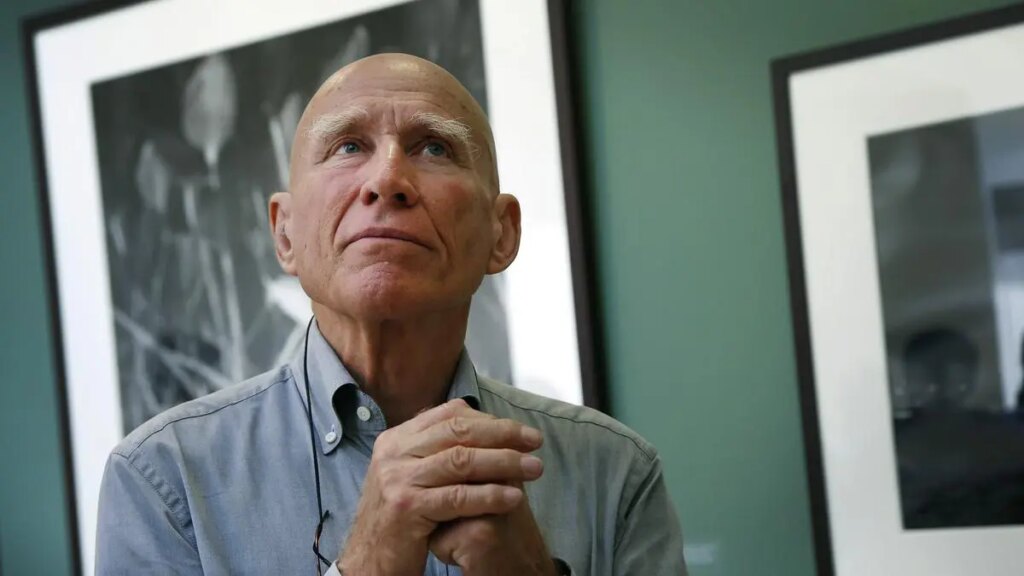

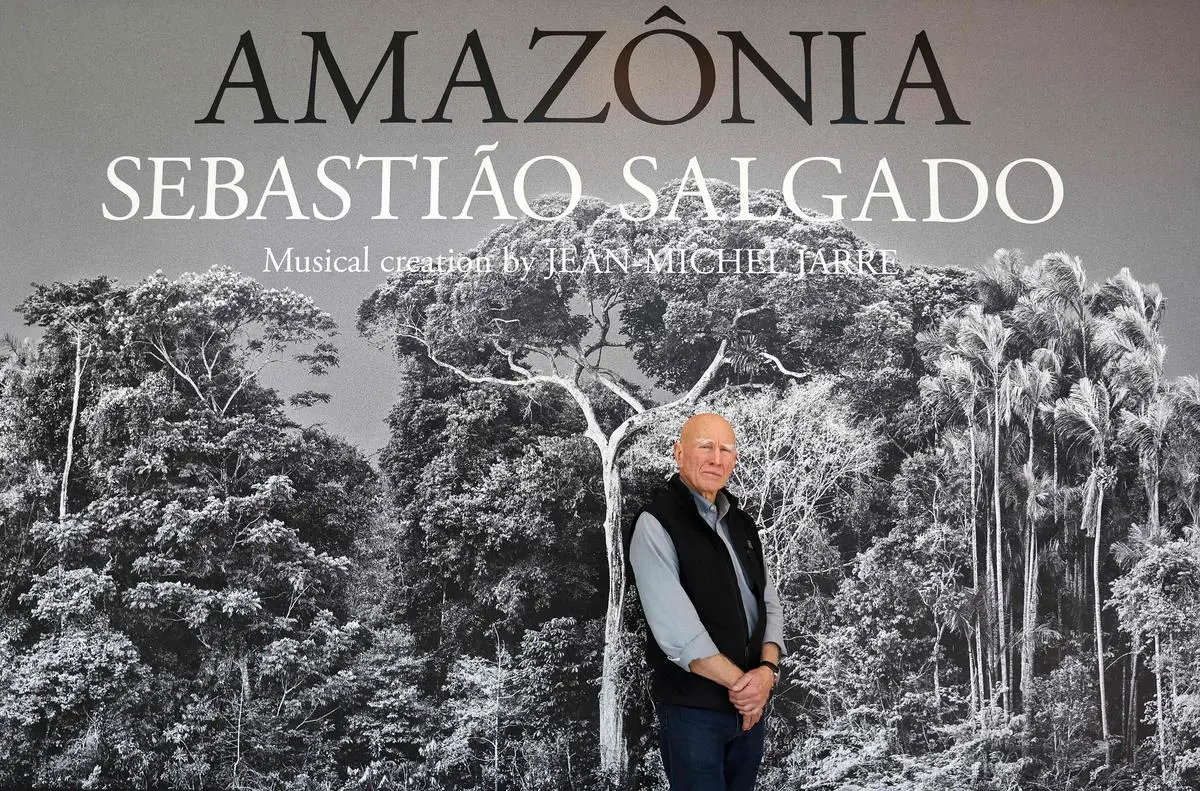

Sebastiao Salgado at a press preview of his exhibit Amazonia at the California Science Center on October 19, 2022 in Los Angeles, California.

| Photo Credit:

MARIO TAMA/AFP

Salgado’s vision was forged from the perspective of the Global South, but it included a keen awareness of global connectivities, inequalities and challenges. Salgado visited 130 countries in the course of his career, often spending long stays with his subjects and immersing himself in their contexts. His vision was truly panoramic, his lens encompassing the indigenous and the landless, those turned ghost-like by starvation and environmental emergencies, the craftsmen and the workers overtaken by industrialisation and mass production, those uprooted and displaced by conflict, war or environmental crisis, those born into precarity and uncertainties, and those whose lives and existence are endangered or precarious.

Documenting the struggle of the dispossesed

Through it all, his gaze was directed at the effects on localities, communities and the environment of the mass phenomena of our age, namely modernisation, industrialisation and globalisation with their attendant upheavals, environmental exploitation, and human and environmental dispersal. His life work was unswervingly focussed on placing photography at the vanguard of the struggle for social and planetary justice.

“His images often portray harsh realities that many may prefer to ignore and they do so with the power to haunt viewers long after they have moved on. ”

To contemplate the corpus of Salgado’s work is not an easy endeavour: his images often portray harsh realities that many may prefer to ignore and they do so with the power to haunt viewers long after they have moved on. Needless to say, his work depended on close and protracted engagement with his subjects, so that the witnessing of their struggles marked his life over and again. Salgado often stated that for his final photo essay “Genesis” he had sought out a happy project, one that focussed on those few, remaining pristine spaces and subjects of our modern world, many of whom were pre-modern or non-human.

To understand Salgado’s photographic mission, one needs to cast the eye backward from “Genesis” over his preceding photo essays, all of which frame different perspectives on his main concerns. What comes to the fore is a sustained preoccupation with the social and the environmental, with people and the planet, within the frame of our global, fast-paced and extremely uneven modernity. The sheer geographic breadth of his work confirms the interconnected dynamics of modernity, the wonderment of nature across the world, and the small, individual heroisms of those who are dispossessed or facing uncertainties. “Genesis” confirms what his previous photo essays have traced: namely, the inseparability of the environmental and the social, of the human and the land—and, above all, the urgency of environmental action and re-envisioning humankind’s place on earth to protect the planet and its life forms.

“Workers emerging from a coal mine. Dhanbad, Bihar State, India,” (1989) by Sebastião Salgado.

| Photo Credit:

Sebastião Salgado

If Salgado was a master of the visual, then this was because his images drew from artistic traditions of chiaroscuro. He brought to photography some of the hallmarks of Renaissance art, framing his subjects in a majestic light, made possible by the nuanced tonality and dramatic contrasts of his black-and-white photography. For the same reason, he was often subject to criticism. The predominant aesthetic that repeated across his images begged the question from many as to whether it was at all right to create such beauty from frailty or suffering. The elite nature of his visual art—for Salgado was without doubt a superb artist of the visual as much as he was a documentarian—and the transfer of harsh realities into high art have troubled many critics.

Also Read | Changpas in Ladakh see life disrupted by climate change

Any doubt about his intent, however, could be laid to rest by turning to the Salgados’ parallel efforts at Instituto Terra in his home town of Aimorés, an ambitious project to counter the slash and burn techniques of cattle farming by repopulating the Atlantic rain forest, nurturing seedlings to transplantation and so recreating a lost habitat. To date, over three million trees have been replanted by Institute Terra.

Salgado’s passing marks the end not only of an extraordinary life devoted to photography as art, document and space of possibility, but also perhaps to the end of an era in photography itself. Whilst working on “Genesis”, he himself made the transition from film to the digital. The ubiquity of photography in the digital age places a great question mark on whether any photographer in the years to come can ever match the sheer breathtaking scale of his monumental work, at once documentary, engaged, and aesthetically hallmarked. Sebastião Salgado is survived by his wife Lélia Wanick, their sons Juliano and Rodrigo, and their grandchildren Flavio and Nara.

Parvati Nair is Professor of Hispanic, Cultural and Migration Studies at Queen Mary University of London. She is the author of A Different Light: The Photography of Sebastião Salgado (Duke University Press, 2011).

Source:https://frontline.thehindu.com/news/sebastiao-salgado-death-photography-global-justice-tribute/article69681718.ece